James Cameron’s first two Terminator films continue to be regarded as two of the best examples of action/sci-fi storytelling of all time. The sequels that followed, despite being supplied with sufficient star power and formed around a familiar mythology, failed to generate the same critical acclaim or fervor from fanboy audiences. This year’s Terminator Genysis, which opened last month, has already been cited as the first picture in a new stand alone trilogy – Terminator 2 (working title) is set for release on May 19, 2017 and Terminator 3 (also working title) has a release date planned as far ahead as June 29, 2018.

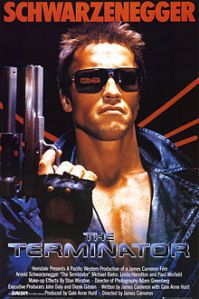

Lightning rarely strikes in the same place twice, let alone 4, or even 5 times successively. Despite this, studios have nowadays become accustomed to dropping buckets of money on the umpteenth iteration of the same worn-out tale – the Terminator franchise being a prime example. Before the most recent film even hit theaters, James Cameron went on record saying that Terminator Genisys is the “real” third Terminator film, effectively writing off the other two features as non-canon. Though Cameron had no direct involvement in the production or filming of Genisys, his endorsement hinted at its potential to re-inject some life into the storyline. But even with the help of the first T-800 himself (the inimitable Arnold Schwarzenegger), it lacked the strength to assume responsibility for yet another reprisal.

Unable to participate in the fourth film Terminator Salvation due to his political pursuits, the former California governor, now 67, quickly slipped back into his former role as cinematic cyborg. The Genysis screenplay explains why the T-800 ages like humans do, using a life-size CGI model of a 37-year old Arnold to represent him as the younger robot from 1984’s original The Terminator. Schwarzenegger had to train twice as hard to get back to the same weight he was in 1991’s Terminator 2: Judgement Day, as Genysis features T-800s from all three different time periods. The overall plot is mired in temporal paradox, as Sarah Connor and Kyle Reese battle both a “killer” app and the nefarious satellite internet-based plague that is Skynet while simultaneously attempting to change the outcome of life in a parallel universe. Too convoluted for casual viewers and too much of a stretch for anyone else who has grown up loving the series, appreciating Genysis requires a full reimagining of time as a linear construct.

After the announcement of the arrival of another Terminator film hit the Internet, comment trolls immediately questioned the need for it — even the most devout fans seemed to agree that Salvation should have effectively closed out the saga. Studios pressed ahead anyways, and Genysis went on to generate relatively lukewarm box office numbers alongside mixed critical reviews. One of the film’s harshest critics, Grantland’s Wesley Morris offered some particularly scathing insight, saying, “It’s neither a surprising work of pop art nor an entertaining piece of crap.” Within the Terminator universe created by Cameron, this film stands out not necessarily for its explicit awfulness, as it is arguably a “better” movie than 2003’s T3 or 2009’s Salvation. However, treading on overly familiar ground, it does little more than dig a deeper grave for the once-great story of robotic apocalypse.

Paramount Studio’s premature hopes for the franchise’s longevity (evidenced by their early announcements of both additional sequels) may be dashed, as it hasn’t truly seen success since the mid-’90s and for many, the lackluster Genisys is just further proof that it’s best years are over. Unfortunately, film studios seem to pay less and less attention to the creation of uniquely compelling characters and plots. This year’s release of Mad Max: Fury Road and Jurassic World, as well as the upcoming Star Wars sequels and the initiation of projects like the all-female Ghostbusters only serve to indicate Hollywood’s increased reliance on the exploitation of familiar, formerly-glorious, success stories. Paramount has suggested that if the film fails overseas (it has an August 23th release date in China) plans may be scrapped for the 2017 and 2018’s Terminator pictures. A disinterested Asian audience might be enough to finally convince executives that there is an important distinction between giving up and knowing when you’ve had enough.

Good films don’t necessarily need critical support, but they do need to tap into something primal within the hearts of audience members. In a world where robots are achieving an ever more powerful presence in our day-to-day life, there’s no reason why the stories we write about them should fail to excite. If Paramount does choose to carry out plans for two additional sequels they would do well to abandon the Terminators completely – today’s technology is surely enough to inspire a new storyline, full of the imaginations and intrigue which made the first two films so great.