Click on images to enlarge.

_________________________________________

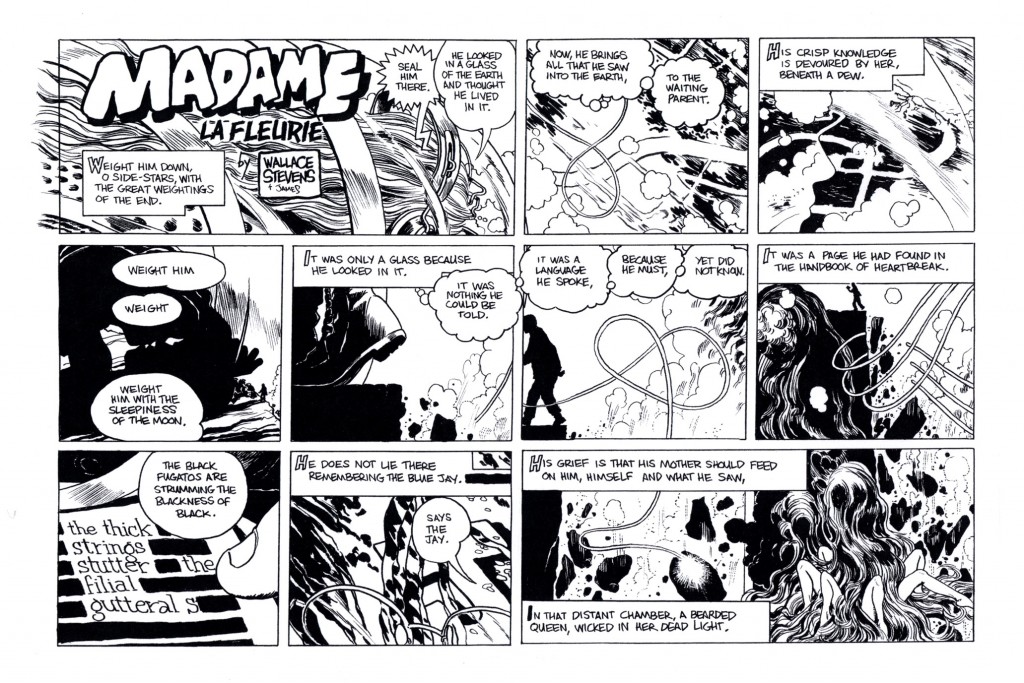

“The impacts of both pictures and words drive more deeply into human awareness than any anthropologist has yet cared to note.”

-Milton Caniff

_________________________________________

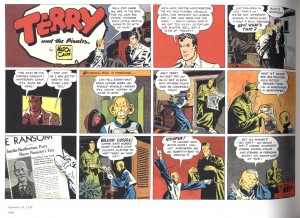

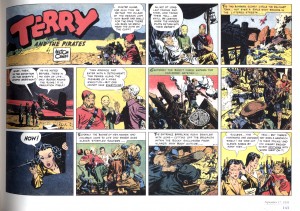

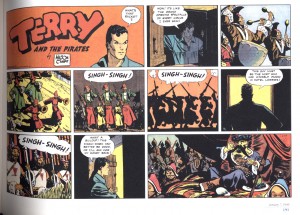

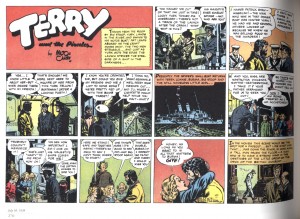

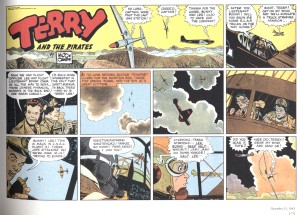

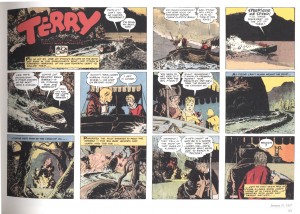

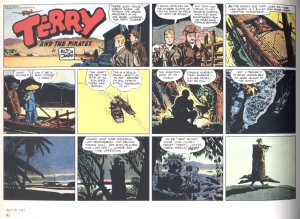

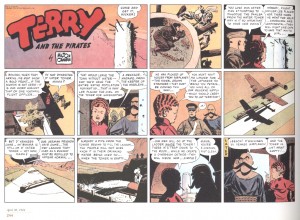

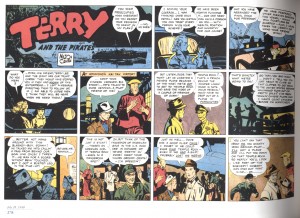

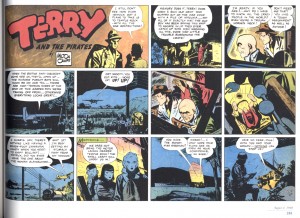

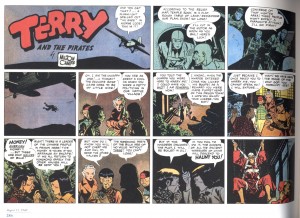

I just read four of IDW’s collections of Terry and the Pirates back-to-back. They comprise one of the most gripping narratives I have seen in comics. They are essential reading for anyone who loves the medium of cartooning and enjoys exciting, involving storytelling. These gorgeous, thick hardcover volumes edited by Dean Mullaney each print two years worth of black and white daily strips and color Sunday pages. The stories certainly read differently in book form than they could have with the protracted exposure of serial doses. Once I was hooked at the outset, I had a hard time putting down any given volume. The relentlessly powerful engine that Caniff stokes pulls the reader along helplessly.

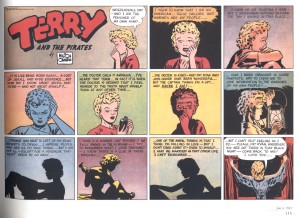

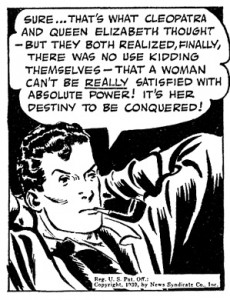

A lot of what Caniff accomplishes here has not been surpassed in comics. Many of the characters resonate strongly with the reader. Throughout, the sensitive handling of Terry’s “coming of age” is impressive. So is the villainy of a host of despicable scoundrels, some of them quite believable as is the case with the wretched Tony Sandhurst. I cared about what happened to Burma, Raven Sherman and Rouge; in this Caniff’s nearest correspondent is Jaime Hernandez. Their characters’ appeal is not only due to their motivation and dialogue but also to the way that the artists are able to put forth their nuance of expression and gesture. Like actors, cartoonists such as Hernandez and Caniff must believe their characters to be able to convey credibility to the reader.

The books boast excellent reproduction and fascinating supplemental essays by Bruce Canwell, Jeet Heer, Russ Maheras and others, Terry-related promotional art and photographs of the artist and his circle. There’s only one down note, in his introduction to Terry V. #2, Pete Hamill repeats a claim that he made in a letter to The Comics Journal (#135, 1990, p.34) years ago, that the millions of people who read the strip did so for the writing rather than the art, citing that because Caniff’s friend Noel Sickles’ strip Scorchy Smith was beautifully drawn but dead in the water story-wise, ergo the story (“that is, the writing”) is what is primarily significant. Hamill seperates the art from story as if the story lies only in the text. Yes, Caniff is a good writer, and yes, there is almost nothing that I can compare to this in scale and quality, but the fact is that the narrative in comics is carried by both text and art. Caniff is one of the greatest exemplars of this.

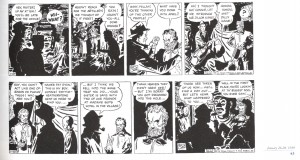

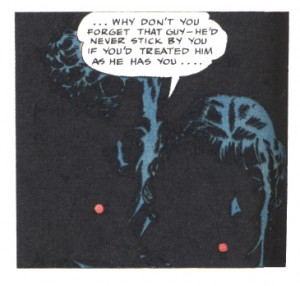

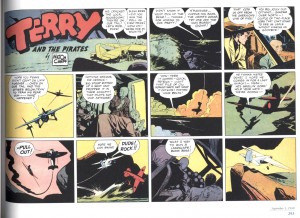

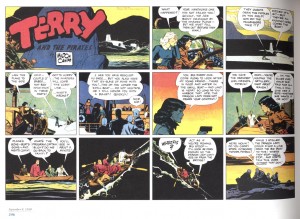

Sickles WAS missing part of the equation—both text and art signify to the reader, both are “read.” Caniff was prodigiously talented at both and it is their interlocking orchestration that marks his mastery. The story would not have had anywhere near the same impact and import to his huge audience if it had been drawn by another artist, if it had been done without Caniff’s sometimes oddly stiff but still expressive figuration and clearly differentiated likenesses, his sense of deep space, composition and dramatic lighting, his facility for exacting observation and reference, his pen and brushwork, his color, the level of developing skill involved in his amazingly nuanced renderings of his characters and their world.

The powerful impact of imagery in Caniff’s work is made clear, though unfortunately in a negative way, by the fact that the work is so tainted by racist depictions. Connie is no more forgivable than is Will Eisner’s Ebony. These characters permeate and compromise the works of their respective creators. To forestall apologism, I do not believe Caniff and Eisner were forced to include these depictions. Both also tended to draw non-racist ethnic characters next to absurdly caricatured ones—as in Eisner where one sees Ebony attempting to woo a more realistically cartooned African-American girl, in Caniff one sees racist depictions of Japanese people and the Chinese Connie interacting with more realistically-rendered images of Chinese people. Connie is omnipresent in Terry and often displays ingenuity and courage, but his visual depiction is irrevocably abhorrent, even if one could find a way to tolerate the obvious glee Caniff invests in the character’s mangling of English.

Still, if one can somehow ignore this mitigating factor, there is much of great value to be found in Terry and the Pirates. At this moment, the work in Volumes 2, 3 and 4 resonates most strongly to me. I have yet to read the final volume, but so far I prefer the stories done before Caniff became more intrinsic to the American war effort. The later stories, as well as those in Caniff’s subsequent strip Steve Canyon have a feel of military formalism that seems a bit less free and alive than the more imaginative earlier adventures. But when it is Pat, Terry, Connie and Big Stoop blasting through stories that are driven by the artist’s superlatively developed female characters such as Burma, April Kane and the Dragon Lady—this is the stuff of great comics.

I scanned pages from several of the volumes to post here, which represent moments that struck me as particularly well-articulated, amazingly drawn or fabulously colored, or that showed places in Caniff’s trajectory that I feel had to have been seen and loved by certain artists, who I may or may not have known were profoundly influenced by Caniff.

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

________________________________________

_________________________________________

________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________