I have been thinking about access in comics studies lately, about the way the availability of resources can be used to steer critical interests in the field. Publishing houses and archivists, collectors and copyright holders, even cultural guardians – there are a lot of people and institutions involved in making decisions about which titles to seek out, preserve, and keep in print. Of course, anyone who works among the ephemera of popular culture faces similar challenges, but my question focuses on the implications for comics scholarship: How does access to materials shape the choices you make about the comics you study, teach, or review?

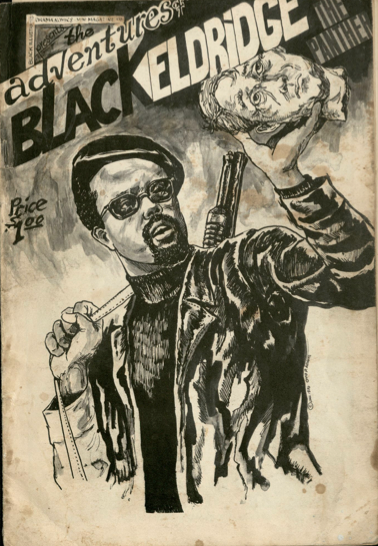

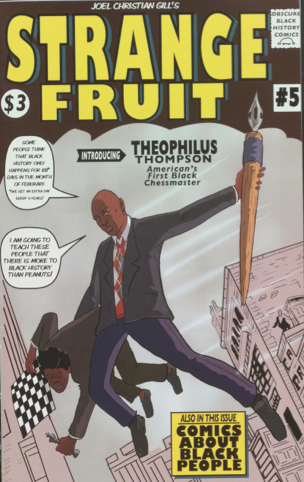

Last week, I visited the comic book archives at the Library of Congress in DC and at Virginia Commonwealth University’s James Branch Cabell Library in Richmond. Although I arrived with a list of rare comics and fanzines that I wanted to read, the best part of spending time in archives was getting the chance to talk with the reference librarians who maintain the collections and know where to look for hidden gems. Thanks to Cindy Jackson at VCU, I got to turn the pages of The Adventures of Black Eldridge: The Panther, a newly-acquired underground comic produced by Ovid P. Adams in 1970. Megan Halsband at the Library of Congress introduced me to Joel Christian Gill’s recent series of Strange Fruit Comics that uses satire and comics culture to dramatize obscure black historical figures (along with great bonus features like “Lil’ Nino Brown in Slumland”).

You may have to travel to Richmond to see Black Eldridge wield his machete against the villains of white supremacy, but Gill blogs about his work online and his Strange Fruit Comics are being collected in a new edition out this June. And it’s a good thing too, because quite a few of the titles I regularly teach in my class on race and comics are now sadly out of print and I don’t know how long I can keep asking students to hunt down used copies.

Questions of access must also take into account the way comics as a form continues to be disparaged ideologically by those in positions of power. Complaints that the College of Charleston forced last year’s incoming students to endure lesbian “pornography” in Alison Bechdel’s graphic novel, Fun Home, also prompted South Carolina State Representative Tommy Stringer to tweet: “Is the instructional ability of CofC teachers so low that they have to use comic books to teach freshman?” The material consequences of this kind of thinking are extremely serious; the state ultimately voted to slash the first-year reading program’s dollars from the college’s budget.

One wonders if Rep. Stringer would level the same accusations of teacher incompetency if the College of Charleston had selected March: Book One for their freshmen reading selection, as Michigan State and Marquette University are doing this fall. U.S. Congressman John Lewis has been signing copies of his graphic novel memoir to standing-room only crowds across the country. In interviews, Lewis along with his co-writer Andrew Aydin and artist Nate Powell have often praised the ability of comics to inspire social change and reviews celebrate the novel’s success as a teaching tool. Furthermore, the 1958 comic book, Martin Luther King and The Montgomery Story, is available for purchase again due, in part, to a reference in Lewis’s graphic novel and the publicity surrounding distribution of the comic book’s translated Arabic edition during the Arab Spring in 2011. I suspect that high schools and colleges will keep these comics in print for a long time.

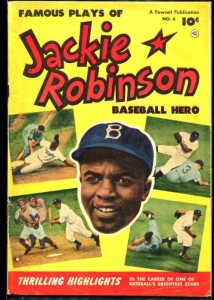

The research that I’m doing now on EC Comics greatly benefits from the initiatives of fans that have worked hard to keep reprints in circulation. The same can’t be said, though, for comics like Fawcett’s Jackie Robinson series, also from the 1950s. Last week, I had the chance to read three issues (three!) from the series, along with one about Joe Louis and Willie Mays, all incredibly fragile and rare. I’m eager to write about these comics, to try to make some kind of meaningful connections with other titles produced during this period. (Who knew that Robinson apprehended cat burglars in his spare time?) But now I’m realizing how important it is that we also work with publishers to make these comics more readily available. If readers can’t get better access to titles like Jackie Robinson or The Adventures of Black Eldridge, how can they become a part of larger critical conversations in comics studies?