Since 1978 I haven’t missed a single isue of The Comics Journal. I won’t go into the many reasons for my devotion, but I’m sure many fellow readers will agree that one of its little pleasures were the numerous lovely, often witty covers it commissioned from some of the best cartoonists and illustrators worldwide.

Below is a small gallery of some of my favorites…

This merry drawing by Brian Bolland for #122 graces what is is easily my favorite TCJ cover. Impeccable execution and fine humor, contrasting boozy reveller John Bull with tight-assed Uncle Sam. The British do often like to mock American puritanism; however the illo also comments on the welcome shake-up of U.S. comics brought about by the artists and writers of the early ’80s “British Invasion”. Try to find a copy; the interviews are some of the most entertaining you’ll likely read. The Kevin O’Neill conversation made me laugh out loud.

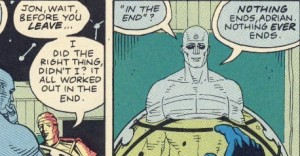

One of those Brit invaders was Bolland’s long-time compadre David Gibbons, who truly rocked the comics scene when he and scripter Alan Moore produced the seminal series Watchmen. One of that comic’s recurring motifs was a circular “smiley” face bisected by a blood splatter. The above cover by Gibbons for issue 116, depicting his drawing desk, evokes that image subliminally.

Two more from across the Atlantic: #279’s crisp composition by Dutch artist Joost Swarte…

…and the incomparable French draftsman Moebius in #118.

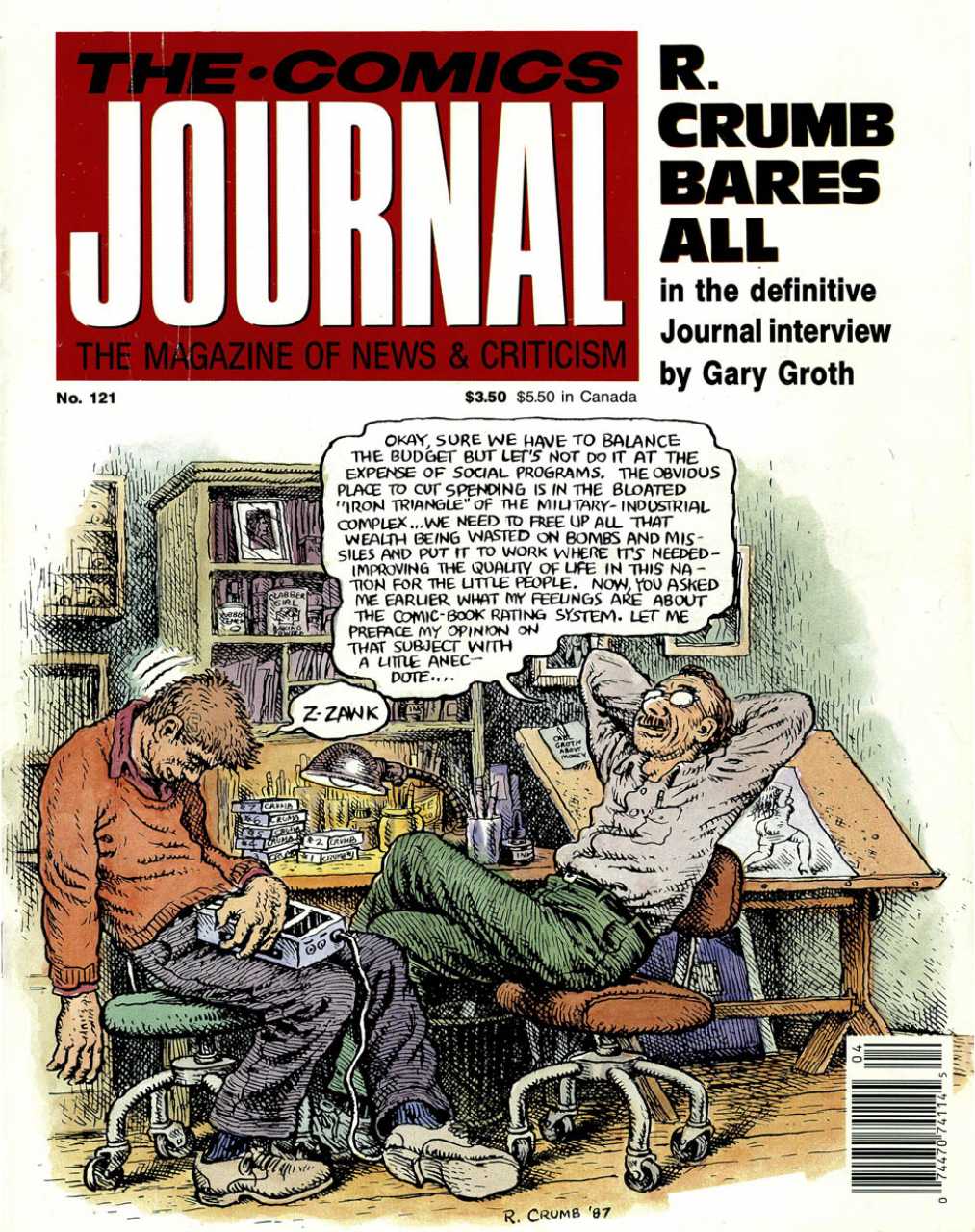

Another very funny cartoon for issue #121 by Robert Crumb. The artist mocks his own pomposity. The chap struggling to stay awake on the left is Journal publisher/editor Gary Groth, who’s made the cover several times — often to be teased… The cover showing the interview process is a recurring theme, one that I enjoy. Three more examples below:

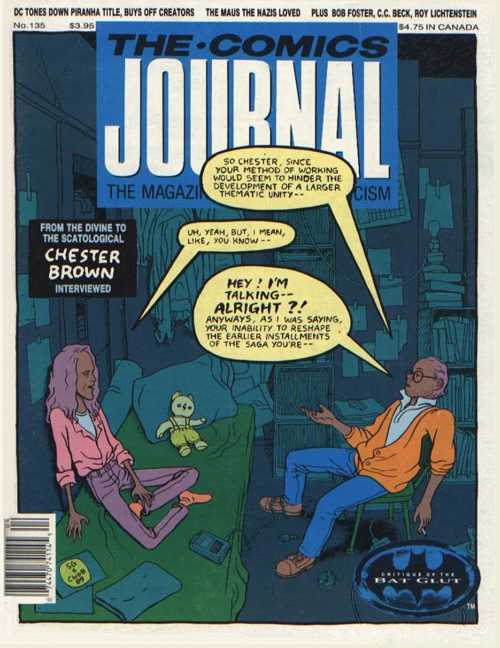

Chester Brown, who drew #135, was indeed a somewhat reticent interviewee faced with a garrulous questioner, as shown.

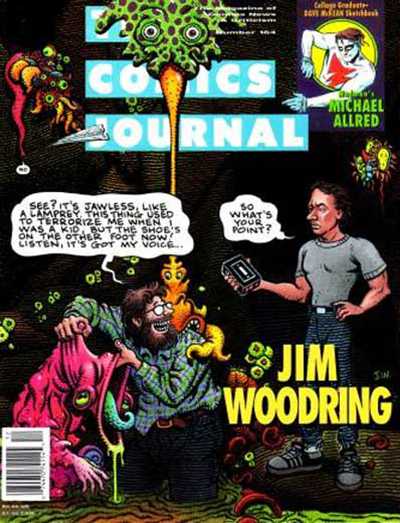

Gary Groth again, drawn by Jim Woodring –another self-satirising artist…

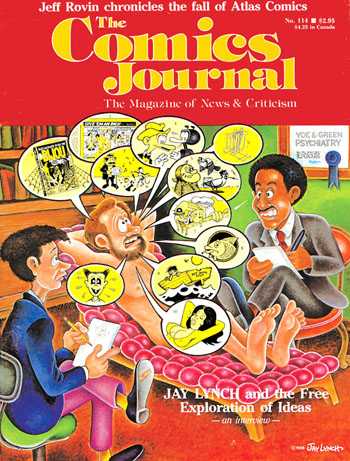

And yet another, the underground comics artist Jay Lynch!

We segue to another underground classic cartoonist, the late Spain Rodriguez, whose gritty urban scene with touches of fantasy encapsulates the diversity of his art.

Spain was one of the artists who illustrated the naturalistic scripts of Harvey Pekar, as was Crumb, who illoed this slice-of-life for #97. (That’s Pekar in the blue coat, with Crumb next to him.)

And another Pekar collaborator was the master of grotesque realism Drew Friedman.

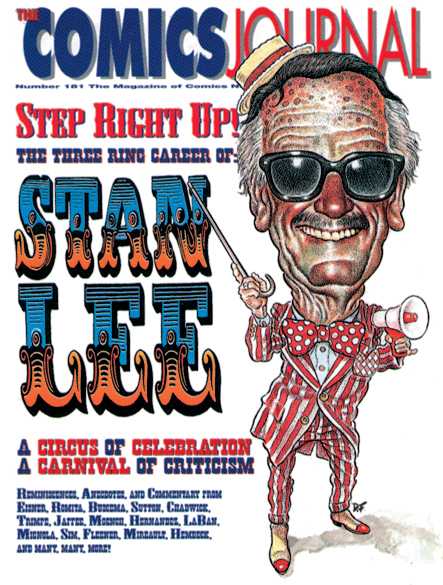

Friedman also contributed this caricature of writer-cum-huckster Stan Lee for #181. Now, sometimes the art direction for the covers is frankly not up to the actual illustration; but this time the AD worked in impeccable harmony with the artist. Below are two more exemplary cases of this.

A terrific character design by Mike Ploog for #274 elegantly set off…

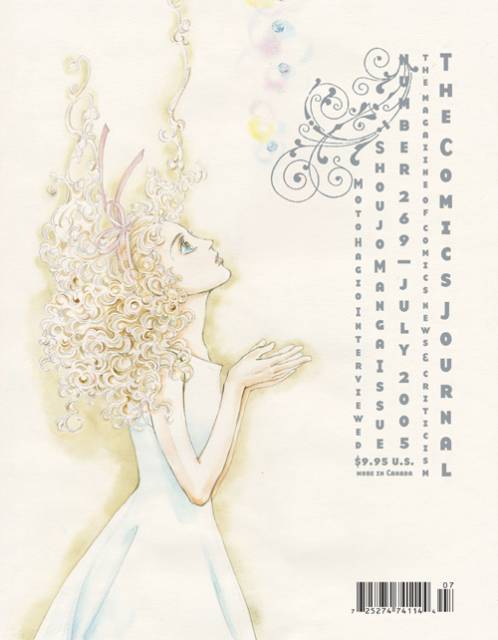

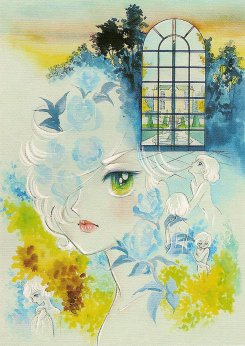

…and a lovely drawing by Moto Hagio for #269; apologies for the light scan, but the cover is truly a delicate confection.

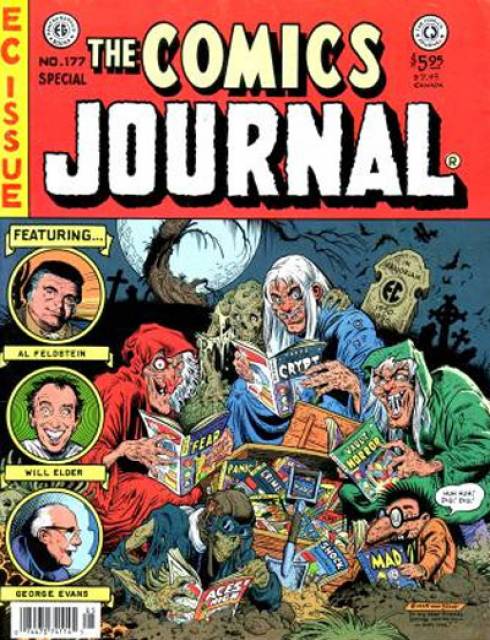

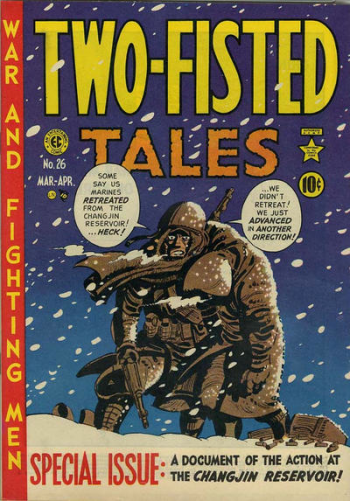

The EC comics from the ’50s were an inspiration to generations of artists.

Notable among them was Bill Stout, who pastiched their cover format twice for the Journal; above, for issue 177…

…and here, for #81. Those three Journal contributors at left? The Critic Keeper is, I presume, Gary Groth; the Old Bitch is probably Marilyn Bethke, one of the most virulent early writers for the mag; but who is the Fault Keeper? Enquiring minds want to know!

Topping off this EC-themed trio: a Mad magazine pastiche by frequent Mad cover artist Kelley Freas for #225. Two of Freas’ iconic characters meet here: Mad mascot Alfred E. Neumann in the red spacesuit; and the Martian from Freas’celebrated cover to Fredric Brown’s comic SF novel, Martians Go Home. Freas is considered by some the greatest science-fiction illustrator of all.

I’m frustrated by this one. Don Simpson drew an awesome wrap-around cover for issue 115, featuring literally dozens of comics characters from around the world. Alas, I could only find a scan for half the cover.

Kevin Nowlan drew this Alternative Comics Cadaver Derby for #98. Apart from Fantagraphics and Last Gasp, all the publishers whose characters are here racing off a cliff are in fact extinct: Eclipse, First, Renegade, Kitchen Sink, and Aardvark-Vanaheim…BTW, Howard Chaykin, the creator of American Flagg, stated that Nowlan’s depiction of that character (2nd from the right) was the best he’d ever seen, including his own.

I am very fond of multi-panel comics as covers, and above is a magnificent example by the mighty Frank Thorne for #280. Here the aged cartoonist, famed for his porn and cheesecake, laughs in the face of his own mortality: a joyful victory of Eros over Thanatos.

Another good comics-as-cover by Dan Clowes.

I simply enjoy the peacefulness of this drawing by Paul Chadwick for #221. The cross-section of snow with burrowing field mouse is a touch typical of the nature-loving artist. Its soothing blues contrast with…

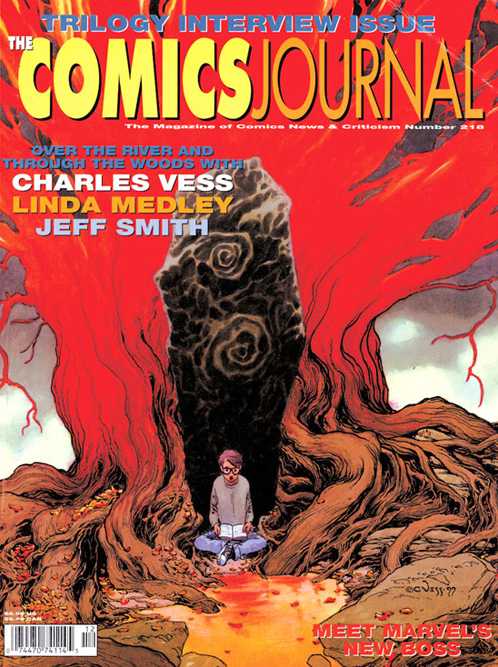

…the fiery eldritch reds of this Charles Vess illustration for #210. It’s hard to compose a symetrical picture that isn’t boring; he pulls it off here.

Another tranquil illustration by Stephen Bissette and John Totleben. Swamp Thing meditates on a newt for #93.

Something of a fanboy guilty pleasure, this. Three stretching superheroes — Jack Cole‘s Plastic Man, Jack Kirby‘s Mr Fantastic, and Carmine Infantino‘s Elongated Man get tied up in knots… The artist is Dennis Fujitake, a prolific contributor to the early Journals and the artist on Journal publisher Fantagraphics” first color comic, Dalgoda, written by Jan Strnad.

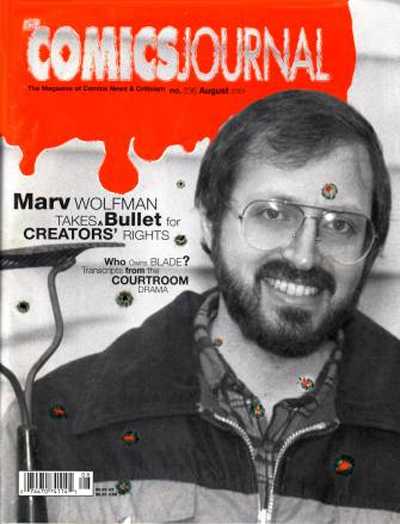

So much for attractive covers. What’s the Journal’s ugliest cover? The late Kim Thompson nominated this:

I can’t honestly disagree, can you?

Let’s finish with a cover from The Comics Journal’s sister publication, Amazing Heroes, by the ever-inventive Bill Sienkiewicz. “Faster than a speedding bullet”, indeed.

Any of your own favorites missing? Browse for them either at mycomicshop or at the Comic Vine.