Before going any further, let’s see what mental images a synopsis like this conjures: “Takao Kasuga is a shy, book-loving high school student who’s had a crush on classmate Saeki Nanako for as long as he can remember. One day, in a moment of lust and foolishness, he steals her gym uniform from class, only to be caught in the act by the quiet and lonely Sawa Nakamura. Knowing she has sway over him, Nakamura forces Kasuga to make a contract with her, or else risk having his secret revealed to the entire class!”

What you might expect from such a synopsis is a harem anime where a bemused, stand-in protagonist finds himself pulled into wacky situations by a cast of cute and quirky moe girls. What you get is one of the most genuinely disturbing and hard to watch anime series of the past 5 years.

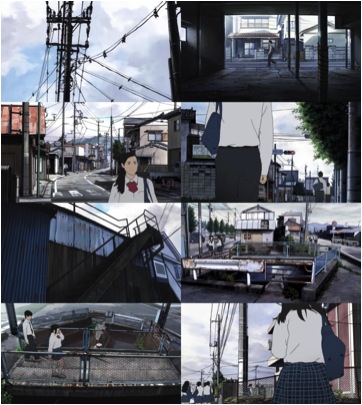

From the outset, the most striking feature of Aku no Hana (The Flowers of Evil) is the use of rotoscoping in all of its character animation. Rather than being originally designed and drawn, the characters of Aku no Hana are played by actors in live action and then painstakingly redrawn in a way that both captures their original movements and gives them an unnerving fluidity. This technique creates a visual juxtaposition between the beautifully drawn and lingered over backgrounds and the airy, almost two-dimensional characters, who are distant drawn without any distinguishing features, like strange, faceless simulacrum posing as flesh-and-blood humans. The effect is distinctly unnerving, and has been a predictable source of outrage in fan communities in Japan and abroad, who wanted a series that sticks to the more standard moe conventions which value cuteness and stylization over realism. While most anime try to draw equal attention to foreground and background in their composition, Aku no Hana specifically prioritizes its environments over the characters; while each scene is painstakingly drawn and lingered on throughout the series, the characters within them remain insubstantial wisps, almost featureless even when viewed up close. There is no typical cuteness to be found in this series. There will be no figurines, no body pillows of its characters. There is instead an empty, boring town, filled with empty, boring people.

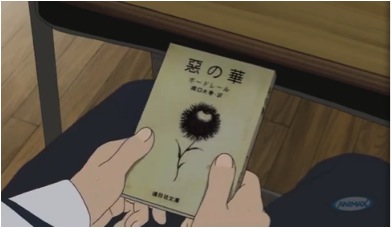

Kasuga Takao knows his town is a boring and hollow place. As he says himself, there’s nothing but “weeds and pachinko parlors here”. He, however, is in his own mind anything but hollow; he is a connoisseur of fine literature, a sensitive and intellectual soul who finds solace from the world in his favorite book of poetry, Charles Baudelaire’s The Flowers of Evil. Those familiar with Baudelaire’s work, of course, will know that the French poet had little interest in providing solace; Baudelaire was a hedonistic, scandalous libertine whose arch-nemesis was the unceasing boredom of modern society, a bête noire as potent in 19th century Paris as it is in 2013’s Japan. Although he thinks himself a poet and intellect inhabiting an ethereal world all of his own, Kasuga quickly demonstrates he’s as fallible as anyone else, and in a moment of irrational lust, steals the gym clothing of his crush, Saeki Nanako, an act witnessed by the class outcast Sawa Nakamura.

Upon seeing Kasuga’s moment of deviance, Nakamura begins to believe that he is different from the rest of their classmates and town, albeit for reasons Kasuga denies; like her, she believes him to be a fellow “deviant”*, someone who sees the world for the sad and boring place that it is and seeks to liven it up with chaos and anarchy. She seeks out Kasuga, and under the threat of revealing his crimes to everyone, forces him to make a “contract” with her, doing whatever she commands to do while she tries to break down “all the walls you’ve built around yourself.”

In a different anime, this premise might make for cute, lighthearted hijinks, but Aku no Hana plays up the inherently disturbing nature of it as often as it can. Over the course of the series, Nakamura forces Kasuga to wear Saeki’s stolen gym clothes as he takes her out on a date, stalks him and constantly undermines his ideas of Saeki being pure and virginal, and ultimately tries to make him confess to his sins to the whole classroom on a blackboard. A peculiar bond develops between Nakamura and Kasuga; even as Kasuga denies being a deviant and clings to his poetry and erudition as a way of distinguishing himself, Nakamura belittles and mocks his false sense of superiority, telling him that beneath it all what he really wants to do is give in to his base principles, fuck Saeki and fuck the world up in turn. In principle, it’s easy to see Nakamura as a standard crazy-anime-girl archetype, without a real personality besides being cute and chaotic. But the reality is more complex; even as Nakamura seeks out chaos and some end to the boredom and insubstantiality of modern life, what she truly desires is a companion, somebody who recognizes the world for what it is and hates it as much as she does. Her desire is not to destroy things, but to escape, to find what lies on “the other side of the hill” beyond the town and the world she knows.

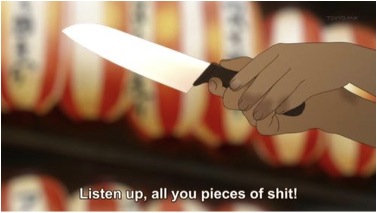

Slowly and methodically, Nakamura breaks down the walls around Kasuga’s psyche, revealing to him the hollowness of his life and self. Midway through the series, she tries to force him to break into their classroom and write all his crimes on the blackboard, something Kasuga point-blank refuses to do. Raging at him, she accuses Kasuga of being just as boring and empty as everybody else, and ultimately tells him never to speak to her again. And for the first time since stealing Saeki’s gym clothes, it is this threat that prompts Kasuga to act autonomously and take action. He admits he’s a deviant, he writes on the board with furious tears in his eyes, and together, he and Nakamura trash the classroom in a blaze of youthful joussiance, neither feeling more alive than in destroying their shit classroom and the shit world it represents.

The anarchic impulses and desire for stable, “real” identity in Aku no Hana are reminiscent of much young adult literature and media, with their shared hatred of the mundane world they’re trapped in, the desire to escape, and the search for meaning in an empty landscape. The key difference, of course, is that while other young adult media valorize their protagonists as seekers of a purer, greater truth, Aku no Hana mercilessly savages such ideas for their naivety. In another series, a sensitive, erudite protagonist like Kasuga might be portrayed as the pure hearted hero, but here, he is mercilessly mocked for the falseness and vapidity of his character. As Nakamura continues to break him down, he also finds himself in conflict with Saeki, who genuinely cares about him even after she learns that he stole her gym clothes. When she learns that he was the one who vandalized their classroom, Kasuga and Nakamura attempt to flee to the place “on the other side of the hill,” only to be confronted once more by Saeki. Realizing he can’t make a choice between the two of them, Kasuga breaks down and admits he doesn’t even understand Baudelaire’s poetry, that he just liked the idea of himself reading it, and that he’s truly, completely empty inside. In the end, both Nakamura and Saeki draw away from him, as both realize he’s not the person they want him to be.

More than anything, Aku no Hana is about identity; it is an exploration on how human beings are supposed to grow and bloom in a world of empty concrete. As I suggested earlier, the aesthetics of Aku no Hana depict the ephemerality of their characters while emphasizing the unchanging nature of their environment; even as individual humans live, breathe, and expire, the concrete and steel they build around them long outlives their own ambitions. In a world where identity and meaning making have been subsumed to commodities and the act of living is conducted in the sterile, alienating urban condition, what choice do people have but go large or go crazy? Surely there are more constructive ways to channel one’s frustrations, but Aku no Hana isn’t interested in them.

Gleefully borrowing from the Decadent literary tradition of 19th century France, the anime savages the idea of modernist progress and the sublimation of human identity to the rigidity of codes and institutions. It wants only to incite violence and chaos, even as it suggests that there is a way to overcome the ennui of modern life through interpersonal relationships and genuine human contact. But it simultaneously is suffused with a postmodern understanding of the world, and recognizes that the antediluvian time when humans could understand one another without the artifice of code, symbol and language dividing them has long passed. All beauty, the beauty Kasuga seeks in his books and in Saeki, the beauty striven towards by the effete constructions of modernism and postmodernism, are compromised and tainted, and the human drive towards something more than emptiness is to blame for it. Beyond the facades, the feeble attempts to rationalize the boringness of quotidian life, a true and utter deviant lurks, a lunatic whose only crime is wanting to find something more, something more than the boring, boring, boring shit hole they’ve found themselves in.

As the first part of the series ends, we find Nakamura and Kasuga’s roles reversed; while Nakamura attempts to leave Kasuga behind, Kasuga asks her to make a contract with him, so they can “crawl out of this shit hole together.” Gone are Kasuga’s self-fulfilling and illusive attempts to define himself as different from everyone else, as superior because of his books and his learning. As Nakamura shows him, there is no path towards self-realization that exists within the system, that isn’t always-already compromised by its subsumation to the authorities and processes that deny autonomy to anyone. To become a person, in the adolescent and neoliberal sense, means to define oneself as free of all others, and so to fulfill the teenage fantasy of becoming more “real” than others implies nothing short of destroying everything that ties you down to the world from whence you came. This is what the final sequence shows; in order to escape the town and the people that inhabit it, Nakamura and Kasuga engage in a surreal whirlwind of violence, a premonition of what they would ultimately have to do for their fantasies of escape to succeed. The liberal idea of individual self-actualization is shown to be a split-level trap; even as one wants to escape and subvert the system, the only way to do so is to give into violence and decadence, and thus fulfill a notion of the individual that places them at the heart of violence itself. It is this paradox, between being someone without any autonomy or claiming it through violence that renders the autonomy and validity of other human lives moot, that Aku no Hana positions itself to engage by the end of its first segment.

I have not read the manga, so I do not know what ultimately happens beyond the first 13 episodes. But in speculating, I can’t help but revisit the ending poem of the series, about a flower which wants to bloom, but should not even exist:

“The flower bloomed. The flower, the flower bloomed. It was terribly afraid of the wind. Nobody had ever seen it before, and it bloomed. Nobody had ever seen it before, and it seemed to bloom. [None had seen it before..and it seemed to bloom. “There’s no flower.” “There shouldn’t be a flower.” Some were convinced it was so. But they were wrong, and it was there. None had ever seen it. It should be harsh to listen to. A flower bloomed that should not have. There it is, yes, there it is. There it is.”

As the series closes, we see the one-eyed flower, depicted on the front of Kasuga’s cover of The Flowers of Evil and a recurring motif elsewhere, finally open its eyes and look towards the viewer. The flower, it seems, has bloomed. The flower has awoken, it has become autonomous, and its time has come. But it is an evil flower. It is a flower that should not exist.

______________

*The word that is used, as far as I’m aware, is hentai, which is usually translated to pervert; however, the elastic use of the term in this series, as it refers to both sexual and social deviance, may be the reason translators use the word “deviant” instead.