Creators haunt their creations, more as ghosts than as intentions.

For example, in 24 there are no ghosts and no intentions. The creators are rigidly outside the action, which runs blithely away under its own power, like a watch dropped in a field. The clock counting down is the guarantor of autonomy, the uninterrupted, self-contained material of narrative. Every time Jack Bauer is given fifteen minutes to reach the drop off point, you can hear the gentle high-concept whisper of the argument from design erasing itself. Cliff-hangers, hackneyed betrayals, and feebly ironic reversals — the gears grind to assure you that the only god lubricating the machine is the absence of a god. Bauer never meets his maker, because the main thing the maker has made is his own unmaking. The ticking time bomb blows the roof firmly onto the world.

Fanny Hill’s world, on the other hand, is laced with holes:

A spirit of curiosity, far from sudden, since I do not know when I was without it, prompted me, without any particular suspicion, or other drift or view, to see what they were, and examine their persons and behaviour. The partition of our rooms was one of those moveable ones that, when taken down, serv’d occasionally to lay them into one, for the conveniency of a large company; and now, my nicest search could not shew me the shadow of a peep-hole, a circumstance which probably had not escap’d the review of the parties on the other side, whom much it stood upon not to be deceived in it; but at length I observed a paper patch of the same colour as the wainscot, which I took to conceal some flaw: but then it was so high, that I was obliged to stand upon a chair to reach it, which I did as softly as possibly, and, with a point of a bodkin, soon pierc’d it. And now, applying my eye close, I commanded the room perfectly, and could see my two young sparks romping and pulling one another about, entirely, to my imagination, in frolic and innocent play.

Who is observing the room to see whom in innocent play? What spirit (of curiosity?) possesses Fanny to look in each convenient flaw? Fanny is writing her epistles to a nameless madam, but there is always an echo in her voice; a sign that her person and behavior are observed and offered through some shadowed peep-hole. The imagined frolic is commanded, and the command is itself part of the pleasure.

D.H. Lawrence’s short story “The Border Line” is also porous. The outside seeps through the world’s borders.

The afternoon grew colder and colder. Philip shivered in bed under the great bolster.

“But it’s a murderous cold! It’s murdering me!” he said.

She did not mind it. She sat abstracted, remote from him, her spirit going out into the frozen evening. A very powerful flow seemed to envelop her in another reality. It was Alan calling to her, holding her. And the hold seemed to grow stronger every hour.

“The Border Line” is a story of a love triangle; Katherine Farquhar married Alan, “unyielding and haughty,” and then, after he died, she married Philip, who “caressed her senses and soothed her.” But Alan, manly and unyielding, is so manly and unyielding that even death doesn’t make him yield, and he comes back for Katherine, like a command or a vow that can’t be unspoken. Katherine is only too happy to become his again; Philip is a puny, soft thing, while Alan from beyond the grave is a dream of potency. The world cracks open, and into it Lawrence inserts his rigid avatar, flushed with power. but bitter cold.

Philip lifted feeble hands, and put them round Katherine’s neck, moaning faintly. Silent, bareheaded, Alan came over to the bed and loosened the sick man’s hands from his wife’s neck, and put them down on the sick man’s own breast.

Philip unfurled his lips and showed his teeth in a ghastly grin of death….But Alan drew her away, drew her to the other bed, in the silent passion of a husband come back from a very long journey.

Philip is dead. Katherine is drawn away into Alan’s arms,embraced by her dead lover and, symbolically, surely dead as well. Lawrence’s journey and story are done, and at the end of them is power and death, or power as death. Alan’s mastery, descending from on high, is so total that nothing can survive it.

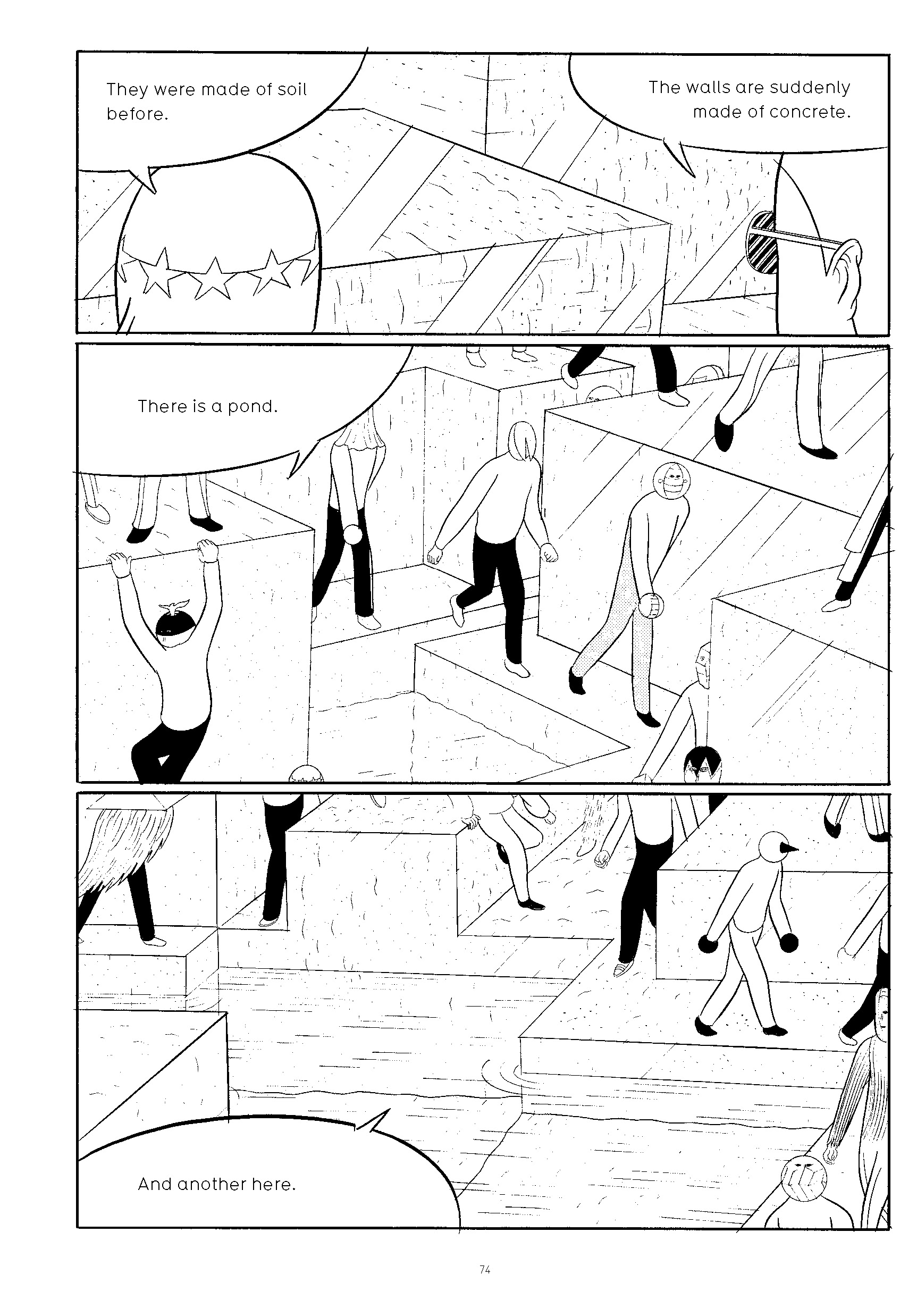

Yuichi Yokoyama’s Garden is not so much open to mastery as a mastery of openness. Inexplicably bizarre-looking characters wander through a seemingly endless landscape littered with the detritus of an ambiguous modernity. Rivers team with office furniture; two-tone mountains rise from the landscape; cameras project everyone’s face onto walls and waterfalls. The seemingly endless stream of people utter repetitive, unanswerable questions: “Why are these things floating in the river?” “Maybe there is someone inside?” “Perhaps it’s a fake city (a dummy)?” It’s “Waiting for Godot” as a combination of Disneyland and Flatland, a geometric theme park with opaque laws. The off-kilter panel shapes combine with the off-kilter views and unusual perspectives so that you, like the characters, often don’t know where you are. Instead of the lines turning into landscapes, the unreadable landscapes resolve back into lines, the mark of Yokoyama’s bewildering hands. The characters wander between his fingers, clockwork ants scrambling through clockwork digits. He’s too big to be seen, but that unassimilable presence is everywhere. We can’t know what he means because he’s the question of meaning itself.