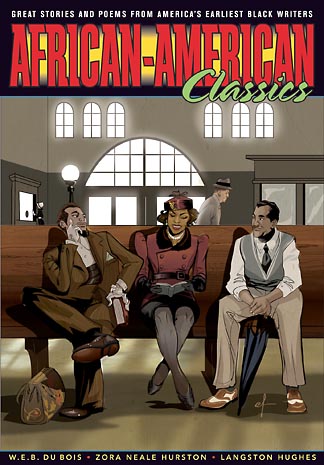

African American Classics is the twenty-second volume of Graphic Classics, an independently-published series that has previously featured comics adaptations of works by writers such as Edgar Allan Poe, Mark Twain, Oscar Wilde, and O. Henry. The earlier selections indicate a predilection for suspense, fantasy, and adventure – genres that traditionally have had a strained relationship with the high literary establishment, but whose vivid narratives are particularly well suited for the comics form.

African American Classics is the twenty-second volume of Graphic Classics, an independently-published series that has previously featured comics adaptations of works by writers such as Edgar Allan Poe, Mark Twain, Oscar Wilde, and O. Henry. The earlier selections indicate a predilection for suspense, fantasy, and adventure – genres that traditionally have had a strained relationship with the high literary establishment, but whose vivid narratives are particularly well suited for the comics form.

Nevertheless, the series takes part in a different kind of conversation when the term “classics” is applied to the poetry and prose of Paul Laurence Dunbar, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and other African American writers. Too often dismissed outright as provincial and derivative, African American literature has struggled with questions of legitimacy since Phillis Wheatley published her book of poems in 1773. “Among the blacks is misery enough, God knows, but no poetry,” Thomas Jefferson wrote eight years later. “Religion indeed has produced a Phyllis Whately but it could not produce a poet.”

The Harlem Renaissance coalesced around a determination to prove Jefferson wrong through the shrewd circulation and celebration of black cultural production (not only in Harlem, but Washington, DC and Chicago too). Anthologies like Alain Locke’s seminal 1925 collection, The New Negro, as well as awards, collaborative journals, and art exhibitions brought together the most promising African American talent, with black writers like James Weldon Johnson making explicit the stakes of their work: “The status of the Negro in the United States is more a question of national mental attitude toward the race than of actual conditions. And nothing will do more to change that mental attitude and raise his status than a demonstration of intellectual parity by the Negro through the production of literature and art.”

The creative appeals of this late-nineteenth and early twentieth-century racial uplift ideology are widely reflected in the literature chosen for African American Classics. A representative selection is Florence Lewis Bentley’s story, “Two Americans” (1921), illustrated by Trevor Von Eeden and adapted by Alex Simmons, in which a black WWI soldier in France rescues an injured white soldier who led the lynch mob that killed his brother, Joe, back in Georgia. Initially the outraged black soldier leaves the white man on the battlefield to die, but then Joe’s spirit appears: “He made me know that all men are brothers, black, white, yellow and brown… and that if I killed in hatred, I would be killing Joe again… just as that white mob did” (21). The comics anthology draws heavily upon stories like these, finely-crafted works aimed at educating readers about the far-reaching costs of racial injustice, often against a backdrop of African American moral exceptionalism, class consciousness, and a deep engagement with the past that is at turns admiring and uncertain.

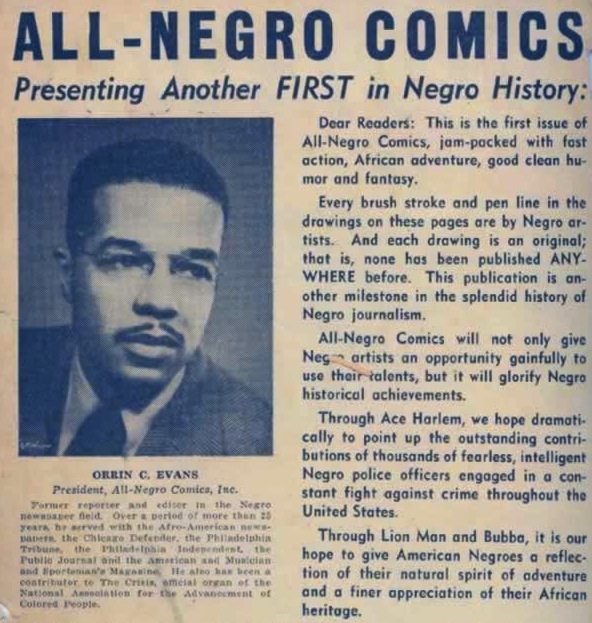

One might suspect that these parables of racial uplift would not signify in the same way that they did in the 1890s or 1920s. That racial injustice persists is without question, but the way we talk about, evaluate, and respond to race and racism has changed. With the most egregious forms of discrimination now criminalized, our society is more attentive to the systemic effects of institutional inequalities, more attuned to the stings of racial micro-aggressions. But African American Classics remains deeply invested in the canonizing demonstration of intellectual parity, not only in terms of content but also in its presentation and marketing. Six decades after Orrin C. Evans opened the first (and last!) issue of All-Negro Comics with the claim that “every brush stroke and pen line in the drawings on these pages are by Negro artists,” African American Classics makes a similar rhetorical appeal, showcasing contemporary African American artists such as volume co-editor Lance Tooks (Narcissa), Kyle Baker (Nat Turner), Jeremy Love (Bayou), Afua Richardson (Genius), John Jennings (The Hole), and writers Christopher Priest (Black Panther, 1998-2003), Mat Johnson (Incognegro), and Alex Simmons (Blackjack). This is not a group of artists and writers that needs to prove their collective self worth. And if we are living in an era that is becoming increasingly more receptive to the “dynamic hyper-creative beauty of modern individualistic Blackness,” should they have to?

What makes African American Classics valuable for me is how the artists and writers adapt the material; the collection’s most provocative selections make formal and aesthetic choices that deepen and complicate my understanding of each work’s potential. Ironically enough, these “graphic” adaptations elevate the visual field of representation in ways that should remind us that literary expressions of African American experience have always been deeply entrenched in the realm of social perception, spectacle, and visibility. The works were originally written to counter claims that the entire character of a people could be arbitrarily determined by what is seen, from skin color to physiognomy to a so-called drop of Negro-stained blood. African American Classics, then, returns the counter-argument of its featured stories to their visual origins and exposes the absurdity of race prejudice in a way that only a comic can.

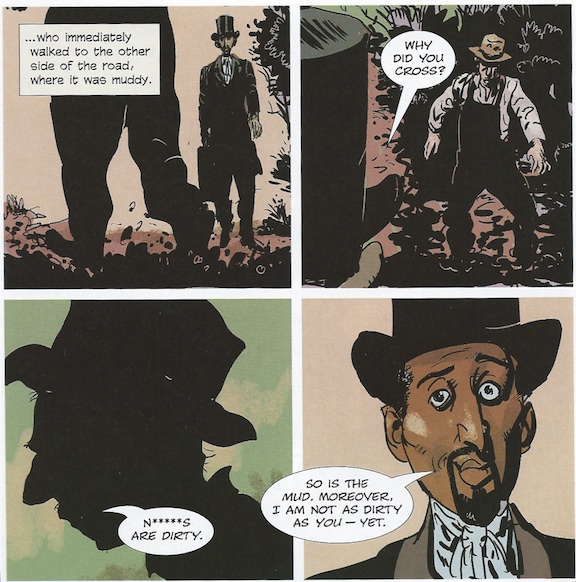

The medium allows Kyle Baker to explore multiple forms of signification in W.E.B. DuBois’s 1907 story “On Being Crazy” in which an upper-class African American man, in a tailored suit and top hat, looks with wry exasperation upon the white people who refuse his business and scramble out of his way. In each instance, empirical logic (and common sense) undermine racial constructs of the period. When a clerk points out, “this is a white hotel,” the main character looks around and responds, “Such a color scheme requires a great deal of cleaning, but I don’t know that I object.” Baker underscores the visual and verbal contradictions that are critical to DuBois’s anti-racist agenda by illustrating how the main character’s unwanted racial presence intrudes again and again into prohibited spaces, even as his body and speech reflect the more palatable codes of education and privilege.

Writer Mat Johnson and artist Randy DuBurke’s adaptation of Jean Toomer’s short story, “Becky” deftly conveys the haunting refrains of his 1922 collection, Cane. The draining light and decay in the long, repetitious panels mark the passage of time in the title character’s life as an outcast in the South. Milton Knight makes very perceptive stylistic choices in Zora Neale Hurston’s play, “Filling Station” (1930), adapted by co-editor Tom Pomplun, by crowding each panel with vibrant hues, elastic bodies, and fierce expressions to make visible Hurston’s outrageous wordplay and folk humor. Also worthy of note is a little-known mystery by Robert W. Bagnall called “Lex Talionis” (1922), adapted by Christopher Priest and illustrate by Jim Webb, in which the design and storyline about an angry white racist injected with a skin-darkening chemical unfold like an issue of Al Feldstein’s Weird Science from 1950.

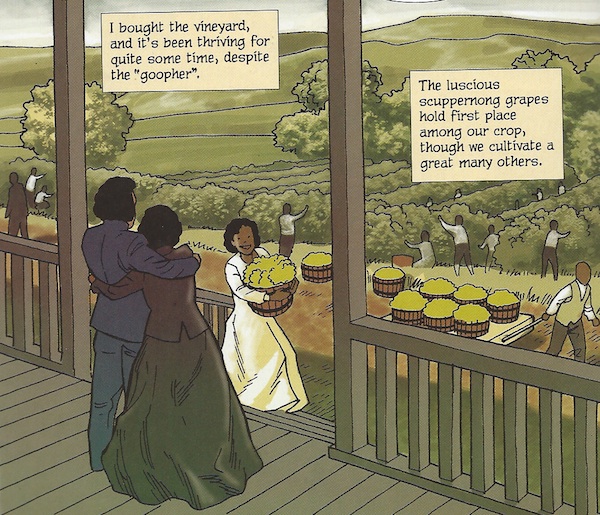

Most surprising, though, is the adaptation of Charles Chesnutt’s story, “The Goophered Grapevine” in which writer Alex Simmons and artist Shepherd Hendrix make a seemingly minor modification that results in a significant reinterpretation. The 1899 collection from which the post-Emancipation tale is drawn, The Conjure Woman, features an elderly black man named Uncle Julius McAdoo who lives on a former plantation in North Carolina where he once worked as a slave. He narrates each tale for the benefit of the land’s new owners, only recently arrived from the North: a white physician named John, and his wife, Ann. While Chesnutt worked within the popular local color format of Joel Chandler Harris’s “Uncle Remus Tales,” the stories Uncle Julius shares emphasize the cruelties enslaved blacks suffered and their desperate attempts to improve their situation. John and Ann are often so moved by the story’s telling that the clever Uncle Julius ultimately ends up enjoying a number of surprising benefits: a new job as their coachman, unrestricted use of the land’s vineyard, and ownership of a nearby church.

But in Hendrix’s illustration, John and Ann appear to be an African American couple. The dress, diction, and demeanor of the doctor and his wife remain in tact, but their position in Chesnutt’s story as gullible listeners shifts across race, class, and regional lines. What are the implications of Uncle Julius’s role as a trickster figure when the wealthy carpetbaggers are black? Certainly there were African Americans who owned property in the South during Reconstruction, but how to describe the looks of pleasure of the black laborers in the vineyard when overseen by the comforting embrace of these new landowners? What is at stake in this utopian reimagining and its potentially troubling subtext of mutual exploitation? Whether purposeful or in error, the visual modification has produced an altogether new and fascinating version of “The Goophered Grapevine.”

In 1963, James Baldwin observed that, “when the country speaks of a ‘new’ Negro, which it has been doing every hour on the hour for decades, it is not really referring to a change in the Negro, which, in any case, it is quite incapable of assessing, but only to a new difficulty in keeping him in his place, to the fact that it encounters him (again! again!) barring yet another door to its spiritual and social ease.” A collection like African American Classics may not be able to do for black comics what the New Negro did for black literature. But I do hope, at the very least, that readers who come across these comics on a bookstore display, a classroom syllabus, or a Black History Month reading list will seek out more than classic reassurances on its pages.

Qiana Whitted is co-editor of the book, Comics and the U.S. South. She also blogs at Pencil, Panel, Page.