My son texts me: “In dungeons and dragons I created hawk-eye, Hulk and Thor”

This is a major breakthrough, even better than downloading superhero mods into Minecraft because it requires his own creative mixing. His uber-Aryan is a human paladin with a demigod destiny and an epic-tier artifact hammer. For the Hulk, you start with a human warden and multi-class him to get a monk’s unarmed strike while wearing bloodweave armor. Mix enchanted arrows and a throwing shield with bow-mastery and brawler talent, and Hawkeye and Captain America are ready to go too. I think he chiseled Iron Man from living metal.

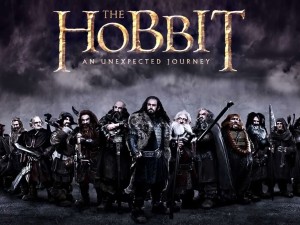

It’s my favorite thing about superhero teams, how gods and aliens and androids can join forces, all their discordant realities merged in the ultimate melting pot of action-packed fantasy. Tolkien didn’t invent the genre, but he assembled one of the first super-teams. He would take it further with Lord of the Rings, but his first team of adventurers mixed dwarves with a hobbit and a human wizard. It was 1937. The Hobbit made a case for diversity in a time of Aryan purity.

Hitler had barred Jews from the German Olympic team the summer before. The “part-Jewish” fencer Helene Mayer was Berlin’s token exception, and she medalled, along with nine other Jewish athletes from other nations. The biggest winner was Jesse Owens with four golds, including a world record set with his relay teammates. Hitler left the stadium rather than shake a non-Aryan hand. In Berlin Owens stayed in all-whites hotel, but back home, he had to use a freight elevator to attend his own banquet. FDR, afraid of losing the Southern vote, snubbed him too.

Hitler wanted to cleanse Germany of ethnic diversity, believing it would return the splendor of ancient Greece and Rome. But go further back, and evolutionary geneticist Mark Thomas calls ancient Europe a “Lord of the Rings-type world,” with multiple human races co-existing for dozens of millennia. In addition to Early Modern Humans (including the hominids formerly known as Cro-Magnon), you got your standard Neanderthals, plus their recently discovered neighbors, the Denisovans. Instead of segregating themselves on separate continents, the three hung out together in Spanish and Siberian caves.

“It is possible,” writes Carl Zimmer for the New York Times, “that there are many extinct human populations that scientists have yet to discover.”

Old school theories didn’t like the idea of Homo sapiens coming in flirting range with other groups after marching out of Africa, but analysis of a Neanderthal toe bone proves the ancient races didn’t keep to their prudish selves. If you have type 2 diabetes, you probably have a branch of Neanderthal relatives on your 50,000-year-old family tree. The gene is biggest in the Americas, so the colony of Virginia was way too late when they passed the hemisphere’s first anti-miscegenation law in 1691. Since early humans didn’t discover Neanderthal love until after they’d exited Africa, Virginia’s slave population was the genetically purest on the continent. Even Englishman Ozzy Osbourne flunked the one-drop rule. He had his DNA sequenced in hopes of finding a “plausible medical reason why I should still be alive” given “the swimming pool or booze” and drugs he’d guzzled. The answer wasn’t racial hygiene.

Denisovans are crashing family reunions too. Europeans carry some Denisovan blood, but the biggest pockets are in Australia and New Guinea, with Brazil and China claiming some of the best Neanderthal-Denisovan mix. Denisovans also share about 8% of their genome with some million-year-old species, so that’s more bad news for Racial Purity Clubs worldwide. We are all, says computational biologist Rasmus Nielsen, “connected to other species.”

Robert E. Howard agrees. The father of sword and sorcery renamed ancient Eurasia “Hyboria” and populated it with a mixed-race of arctic warriors descended from the lost continent of Thuria. The survivors of Atlantis devolved into ape-men, and the former Lemurians came westward, “overthrowing the pre-humans of the south.” This is about 20,000 years ago, after Neanderthals and Denisovans had given way to Homo sapiens. Howard published his first Conan the Cimmerian story in 1932. Conan’s people would evolve into Celts by 9500 BC and Conan into Arnold Schwarzenegger by 1982.“The origins of the other races of the modern world,” Howard writes, “may be similarly traced. In almost every case, older far than they realize, their history stretches back into the mists of the forgotten Hyborian Age…”

Howard committed suicide in June 1936, three weeks before Jesse Owens took his first Olympic gold. That left the Weird Tales realm of sword and sorcery undefended when Tolkien invaded the following year. Like any conqueror, he renamed everything, so Hyboria became Middle-earth. Both ages took place in Earth’s lost history, though Tolkien admits “it would be difficult to fit the lands and events (or ‘cultures’) into such evidence as we possess, archaeological or geological, concerning the nearer or remoter part of what is now called Europe.”

Tolkien’s reign ended with his death in 1973, and the realm was again defenseless during the Dungeons & Dragons invasion of 1974. I dabbled in a game or two with college roommates in the early 80s and now order second-hand copies of user guides and monster manuals for my son who organizes weekend adventures with fellow middle schoolers. I even found him a 2000 Marvel mini-series called Avataarz, featuring D&D versions of Captain America, the Hulk, Hawkeye and other sundry Avengers. He was disappointed it didn’t include their character sheets, but he’s good at building his own. Fantasy is in his blood.

He and my wife and I watched The Hobbit parts 1 and 2 together and have been waiting for the last installment. We skipped the Conan the Barbarian reboot, as did most of the world’s Cimmerian-descended population, but rumor has it Arnold will be returning to Hyboria soon. His last super-team included Grace Jones and Wilt Chamberlain, but I’m sure Hollywood can assemble an even more discordant melting pot of a cast. That’s what the genre is all about.