Tom Gill is a professor at Meiji Gakuin University. This piece first appeared in IJOCA (the International Journal of Comic Art.)

_______________________

“Yoshiharu Tsuge is arguably Japan’s premier eccentric manga artist… he has probably had more written about him than he has himself created.” (Schodt 1996: 200).

Can there be any other manga artist who has been so lavishly praised in the English language and yet been so little read or understood? To date only three short comics have been translated into English (Tsuge 1985, 1990, 2003) [1] a few more into French (Tsuge 2004), and outside the Japanese-reading world, even the most avid manga fans have little idea what Tsuge is all about, beyond a vague awareness that he is difficult, dark and perhaps, surrealist. He is typically accorded a few paragraphs in general surveys of postwar manga, but there is only a single short paper devoted specifically to his own work published on paper in English (Marechal 2005). In Japan he is revered by anyone who takes manga seriously. Five films have been made out of his comics and nine have been adapted for TV. He remains a towering figure, frequently referenced and occasionally parodied, although he has not published any new manga since 1987. I am now engaged in making tentative first steps towards the close reading of word and image in Tsuge that has not hitherto been attempted in English.

Tsuge became famous through his work for the celebrated alternative magazine, Garo, and his work can conveniently be divided into three periods: pre-Garo, Garoand post-Garo. Before Garo, Tsuge was a self-confessed hack, turning out large volumes of hard-boiled manga in the gekiga style pioneered by the likes of Yoshiro Tatsumi, many of them published in pulp magazines designed for pay-libraries. Tsuge churned out gangster stories, samurai yarns, westerns, sci-fi, horror – whatever would sell. Most of these stories are unrelentingly noir – nihilistic yarns that end badly. For example – in ‘Obake Entotsu’ (Ghost Chimney, 1958), a yarn set in a tough industrial city, a particular factory chimney gets a reputation among the chimney sweeps for being unlucky after a series of nine fatal accidents. No-one will dare clean it – except one man, desperate for work after a lengthy spell of unemployment. He ascends the chimney in the midst of a rainstorm – and sure enough, loses his footing and falls to his death. In ‘Shakunetsu no Taiyô no Shita ni’ (Under a Red-Hot Sun, 1960) a group of men from various countries fall into a treacherous pit while being driven to see the pyramids by an Egyptian guide, are trapped there for a week and nearly fried to death, when a rescue helicopter arrives – only for them to accidentally kill the pilot in the rush to get on, and then crash the helicopter, so they are going to be fried to death after all. In ‘Nezumi’ (Mice, 1965) a couple of mice stow away on a space freighter, breed a massive colony, eat the spaceship’s stores and then devour the crew as well.

I hope these very brief summaries give something of the flavor of Tsuge’s pre-Garo output. Many of them are comparable to the boys’ own tales of the British tradition, except with a heavier emphasis on doom. The drawing is dynamic, but nowhere near as sophisticated as in his later work. They are clearly works that have been drawn in a hurry, for cash.

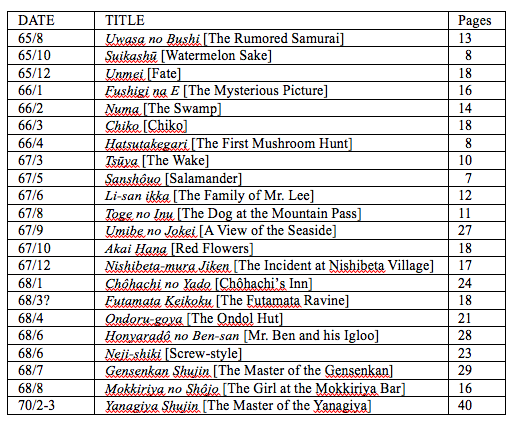

Tsuge was out of work, depressed and contemplating suicide, when he was contacted by Katsuichi Nagai, the legendary editor of Garo. Nagai coaxed him back to the drawing board, and gave him unprecedented editorial freedom. From August 1965 to March 1970, Tsuge would publish 22 manga in Garo (table 1). The first four were only mildly interesting, but the fifth, published in February 1966, would be remembered as Tsuge’s breakthrough work – Numa (The Swamp). This and a dozen more of his Garo manga turned Tsuge into a counter-culture hero. Somehow he had found a way to reach deep into the well of his own sub-consciousness, to produce a string of cameos that were masterpieces of both art and literature – the holy grail of any manga artist. This too, was the moment when “Tsuge helped to free manga from the strictures of narrative and sought a more poetic grammar for them” (Gravett 2004: 134). The best of the Garo works dispense with conventional plot and are full of ambiguity, inviting the reader to engage in interpreting multivalent dream works. After Numa, no-one would ever get killed in a Tsuge manga again; there would be no violence except for some ambiguous cases of sexual assault that I will discuss in another paper; and there would be no more reliance on the stereotyped formulas of gangster yarns, sci-fi etc. Instead, Tsuge came up with works of striking originality.

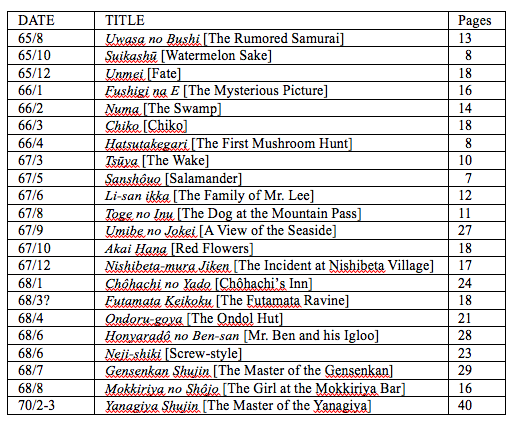

Table 1: Yoshiharu Tsuge’s 22 manga published in Garo

After he parted from Garo, Tsuge published nothing for two years. He then re-emerged with a new style, or perhaps a pair of styles. Some of the new works were based closely on erotic or horrific dreams and fantasies; others were autobiographical, based on his married life with his wife and son. The Garo period protagonist is always a single male (except for ‘Salamander,’ which is narrated by a salamander); the post-Garo protagonist is a family man and much of their interest comes from the family dynamic. There is a sardonic humor to many of these later works, reflecting on the various unsuccessful attempts made by a struggling manga artist to find alternative employment, for example by recycling old cameras or selling stones found on the riverbed as objets d’art. Sometimes social realism gives way to magical realism, as in the story of a man who strongly resembles a bird and makes a living by enticing birds to him and selling them to pet shops. The emotional coloring of these post- Garo pieces grows steadily darker, culminating in the harrowing Ribetsu (Parting; June 1987), describing the break-up of a sexual relationship followed by an almost-successful suicide attempt. To this day, that remains the last manga that Tsuge ever published.

There are various theories as to why so little of Tsuge’s work has been translated. Some say that the work is too challenging to interest mainstream publishers, others that Tsuge has usually refused to allow his work to be translated because he does not like the way manga tend to be “flipped” when translated into English. Yet another rumour has it that Tsuge promised the translation rights to some long lost friend in American who has never made use of them. Whatever the reason, it has been almost impossible to get close to most of Tsuge’s work without a knowledge of Japanese. As one who has lived in Japan for twenty years and been reading Tsuge’s cartoons in the original Japanese for most of that time, I now propose to take a close look at one of the more interesting works from Tsuge’s Garo period: ‘The Incident at Nishibeta Village.’ It was published just two months after ‘Akai Hana’ (Red Flowers), which is one of the few Tsuge works available in English (Tsuge 1985), and has been discussed at some length by Ng Suat Tong.(Ng 2010). In a sense they are companion pieces, both featuring the same hero, a wandering fisherman who finds himself caught up in some unsettling developments in an alien milieu.

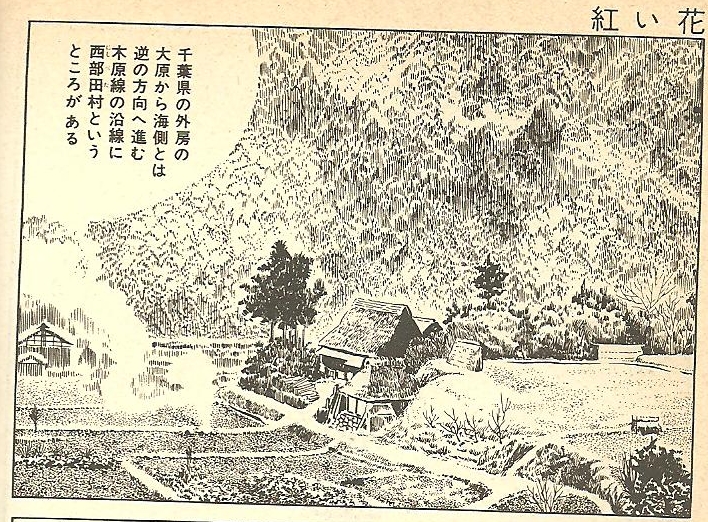

This story is set in Chiba prefecture, just to the east of Tokyo. The south end of the prefecture is the Bôsô peninsula. It is a largely rural area, far less popular with holidaymakers than the fashionable Izu peninsula on the opposite side of Tokyo, having far fewer hot springs. Anyone who visits Bôsô will be surprised to find some quite lonely, depopulated areas, barely an hour’s train ride from Tokyo. Tsuge spent part of his childhood there and has travelled there all his life. The lonely Bôsô landscape features in a number of Tsuge works. The inspiration for this story came from a fishing trip he made to Nishibeta with friend and fellow manga master Shirato Sanpei, in which Shirato managed to get his leg trapped in a hole driven into rock to take a construction peg (Tsuge and Gondô 1993 vol. 2: 94).

In the story, a keen amateur fisherman comes to the village of Nishibeta, on the east side of the Bôsô peninsula, in hopes of catching some dace (haya) at an S-shaped stretch of the Isumi river. The village is quite carefully described and really exists. It has a mild climate and thus is the location of a mental institution called the Nishibeta Sanatorium. This also exists, although in reality it is named the Ôtaki Sanatorium, Ôtaki being a nearby town.

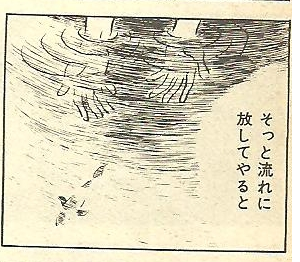

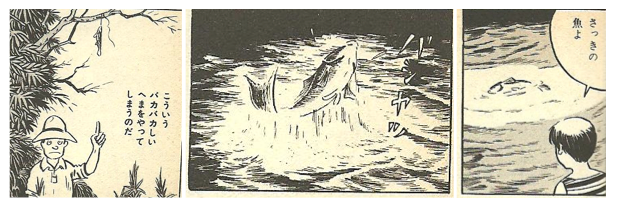

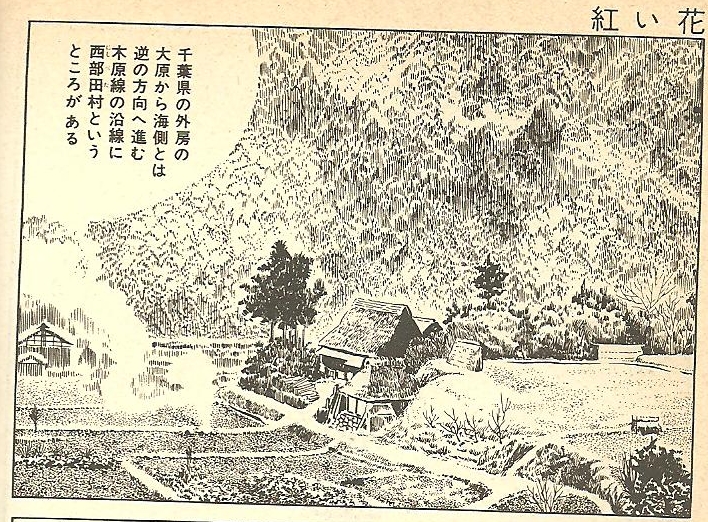

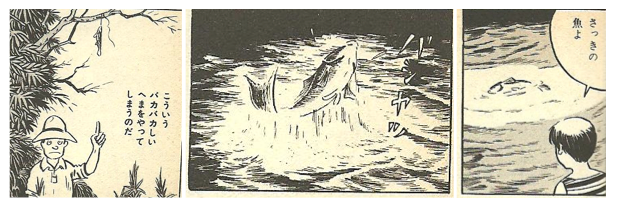

Fig. 1 Opening frame of ‘Nishibeta-mura Jiken.’ Text describes location of the village. [2].

Our hero walks past the sanatorium on his way to a fishing spot. He can see the inmates doing radio calisthenics when he peeps through the fence. The only problem with the fishing spot is the dense undergrowth around it – one can easily get the line caught in overhanging branches. We see an example, which ends with a dead dace hanging from the branch of a tree, the line having broken, out of reach of the fisherman. It is presented as comical (fig. 2 left), but this accidental hanging recalls an earlier manga, Umibe no Jokei (A View of the Sea, the one before Red Flowers) in which the protagonists happen to see a fish get caught by a fisherman standing on a high cliff but then fall back into the water as the line snaps (fig. 2 center). They later see it floating dead (fig. 2 right) – presumably killed on impact. So both stories feature a fishing motif, and both show us the rather rare outcome where the fish escapes the fisherman but nonetheless perishes. If we are looking for a cheap metaphor, in which we can empathize with the fisherman making a catch or with the fish getting away, we will be disappointed; Tsuge permits neither.

Fig. 2: ‘Nishibeta’ p. 3, ‘Umibe no Jokei’ pp. 7, 12

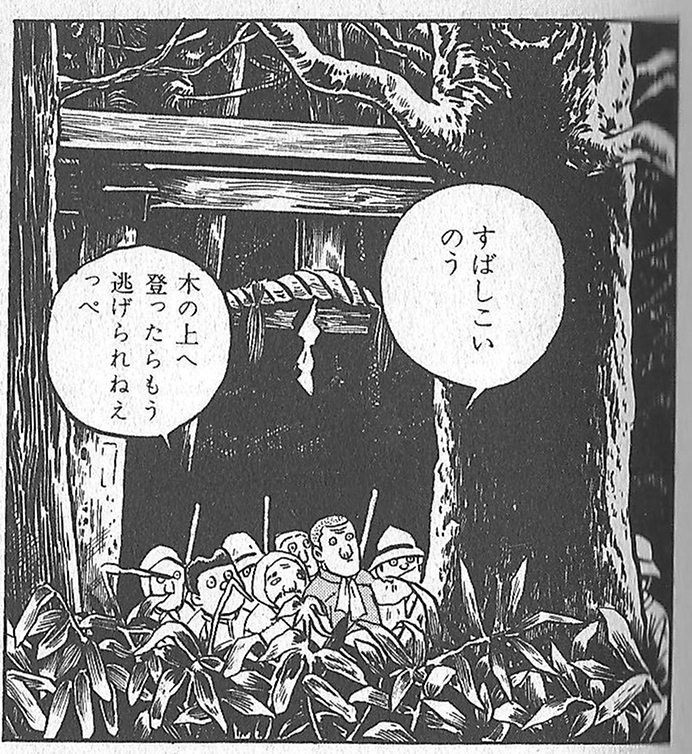

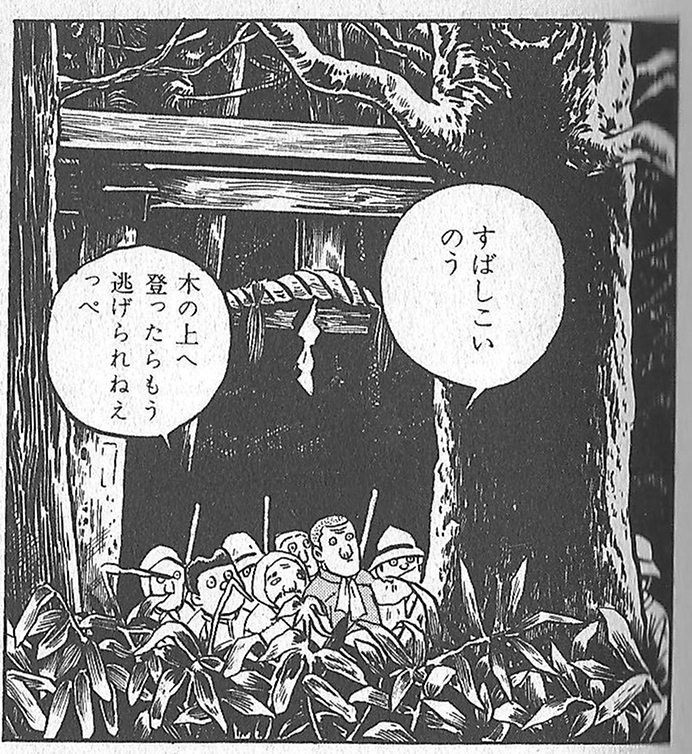

Tsuge employs an ambiguous narrative style as he leads us into the story – he starts out talking in general terms about things that can happen when one visits the place, but then it turns out that the incident with the fish is in the here and now, as he is spotted with the evidence of his embarrassing mistake by the local inn-keeper (at whose establishment he is staying), who warns him that one of the patients has escaped from the sanatorium. The village is in uproar – this is no time to be fishing. The two men run back to the village, where a search party is organized. They divide into two, going round the mountain from opposite directions to cut off the escapee. The villagers are in a state of high excitement; they are drawn comically (fig. 3) in a style reminiscent of Shigeru Mizuki, for whom Tsuge had recently been working as an assistant. Tsuge also admits to literary influence from the humorous novels of Masaji Ibuse (Tsuge and Gondô 1993: 94).

Fig. 3 The search party

Two of the villages claim to have seen the escaped lunatic near the geta (sandal) factory. Note that manufacturing geta is a traditional occupation of the Burakumin outcaste minority in Japan. It is not uncommon for culturally polluted facilities like mental hospitals to be sited in or near Burakumin districts, in a system of nested discrimination whereby one discriminated group is made to put up with another.

The hero nervously says “we’re not going to kill him are we?” He gets no reply, so asks again. “Depends on the circumstances… if he tries to bite us, well, anyone would strike back…” says one villager, pensively scratching his chin.

There’s a false alarm at an oak tree (kashinoki) by the village shrine, an occasion for comic by-play among the rustics. An old man called Sei-chan claims to have seen the lunatic climb up a huge tree next to the torii gate. Another says no man could climb that tree – it has a massive aodaishô (‘Green General’; the Japanese Rat Snake; it grows up to two yards in length) living in it. The old man retorts that he caught a glimpse of the lunatic’s yukata. The other man says it could have been a horned owl (mimizuku). A young boy climbs up the tree and puts his hand in a hole to confirm that there is an owl there. It gradually becomes apparent that the lunatic could not have climbed the tree, and Sei-chan is humiliated. In a last attempt at self-defense, he claims he heard the man cry out, something like kôn. But he has lost all credibility and the company concludes that he must have heard the sound of a kitsunetsuki – a woman possessed by a fox spirit – and mistaken that for the voice of the lunatic.

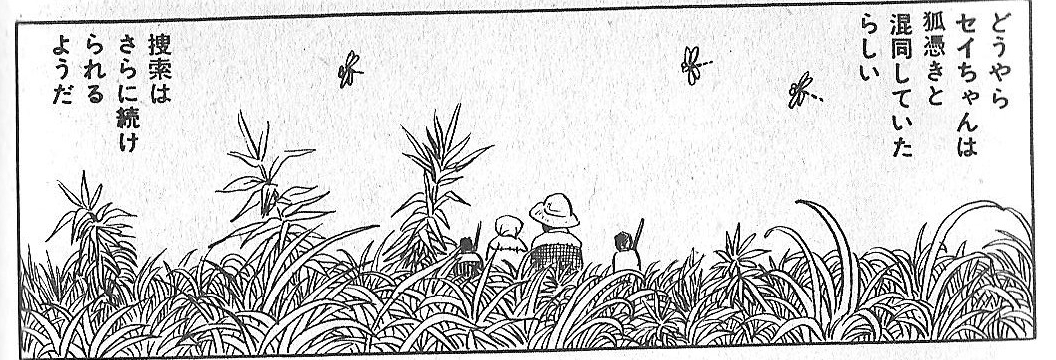

Clearly the villagers are deeply confused. One moment they are arguing about snakes, then owls, then fox spirits. They have no idea as to what shape or manner this alleged lunatic might really have. Ironically, kitsunetsuki happens to be the best-known variety of possession by a familiar – often used as an explanation for madness in early-modern Japan. They are blissfully unaware of that irony. The villagers appear lost, physically as well as intellectually, several times depicted as a little knot of humanity in a dense, impenetrable jungle (fig. 4)

Fig. 4: The shrine in the jungle

As all this plays out, our hero’s fear of the escapee shifts to a feeling of sympathy, as we would expect from Tsuge. He comments: “As I am so weak myself, I am always moved by weak people.” (Tsuge and Gondô, 1993(2): 95). [3]. He leaves the search party, an event we see through his eyes (fig. 5), heading upstream through fields thick with wild chrysanthemums (nogiku), thinking of doing some more fishing.

Fig. 5: Watching the search party disappear

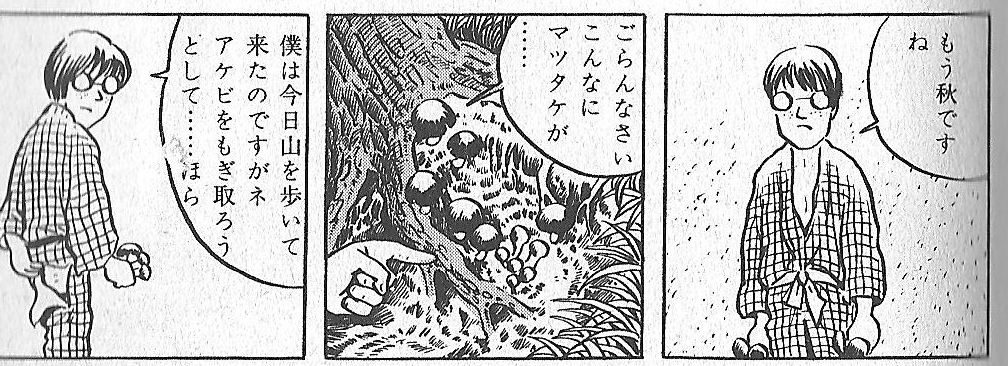

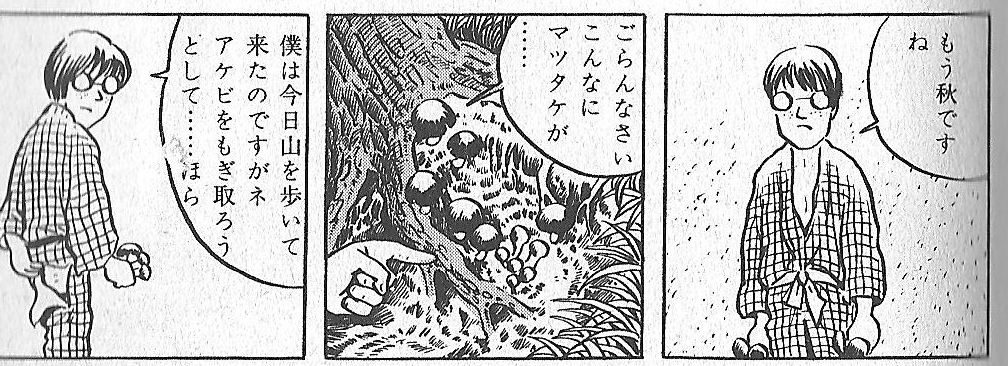

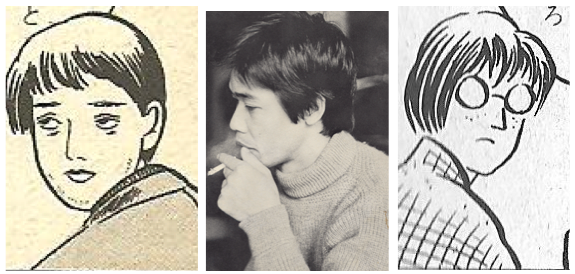

On the path he bumps into the escapee – on his haunches, looking for matsutake mushrooms in the undergrowth by the path. There can be no mistake – he is dressed in a yukata (a light kimono) and plastic slippers with the name of the sanatorium written on them. He is a tall, thin youth, with round spectacles and floppy hair. When he sees our hero he says “Well, autumn’s already here” (fig. 6 right). He shows hero a large clump of mushrooms growing in a hollow at the foot of a pine tree to prove the point (fig. 6 center), then indicates a tear in his yukata he got while trying to grab some akebia fruit (fig. 6 left).

Fig. 6: Encountering the escapee

Then he notices hero’s fishing tackle and excitedly offers to show him an excellent dace fishing spot. On the way he tells hero he is from the nearby town of Mobara; that his family runs a western-style clothes shop; and that he had to drop out of his second year at Chiba Commercial University due to illness. Hero takes the latter as an oblique reference to his stay in the sanatorium, but overall finds that the youth seems perfectly normal.

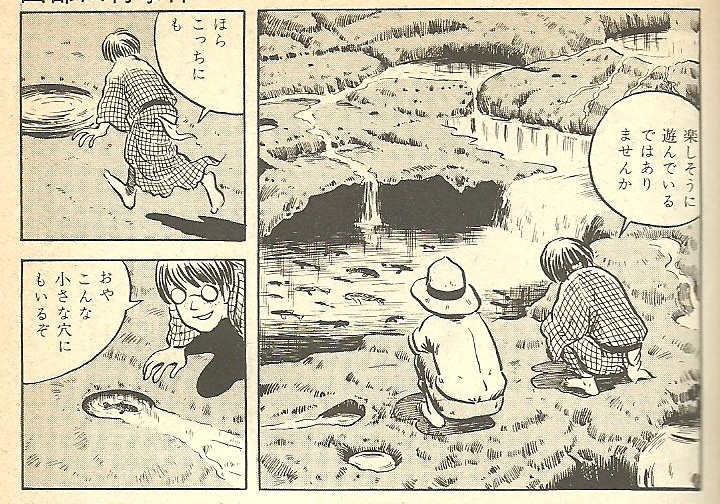

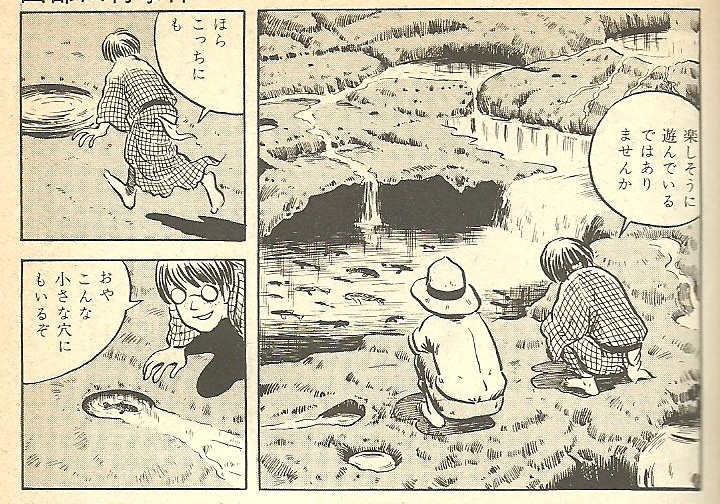

Fig. 7: A good spot for dace

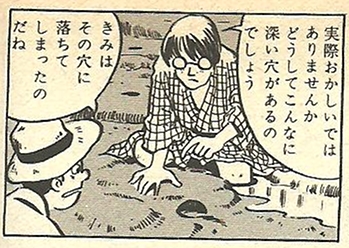

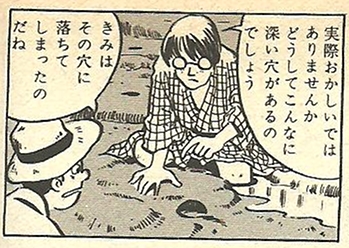

They reach the spot – a system of rock pools just below a dam on the way down the mountain side. The pools are teeming with dace. “They seem to be having fun playing around, no?” says the youth (fig. 7 right). He points out that even little holes in the rock have dace swimming in them (fig. 7 left). The only trouble is – it’s too easy. Hero wants a challenge, to swing his rod. Still, he decides to do a little easy fishing with the youth, goes to his tackle box and bites off a length of fishing line for him. But when he returns, he finds the youth has his leg stuck in one of the little holes in the rock. The youth comments: “It’s really strange, don’t you think? Why should there be such a deep hole in a place like this?” (fig. 8). Hero speculates that it might have been caused by a peg being driven into the stone when the nearby dam was being built. There is a live fish caught under the youth’s foot, and it is tickling him to death.

Fig. 8: The escapee trapped in a fishing hole

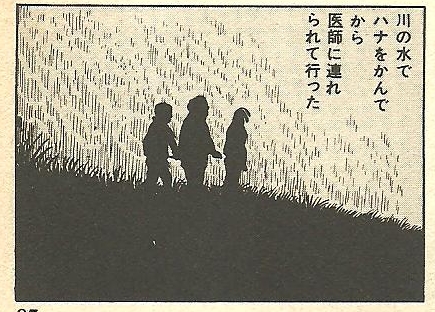

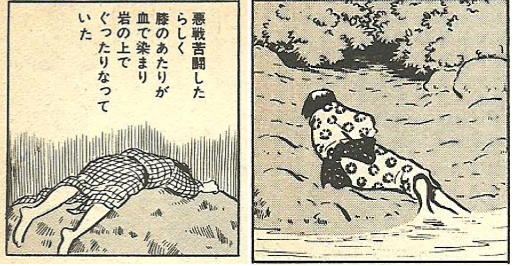

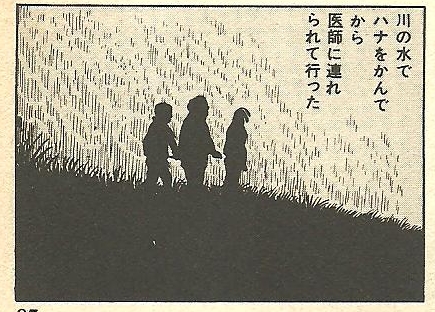

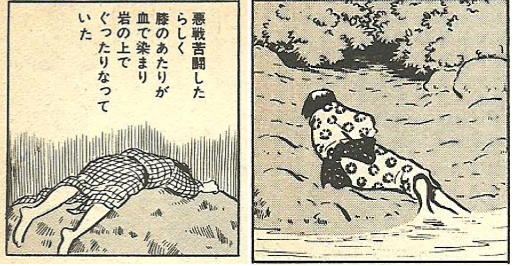

Hero cannot pull him out, so he goes for help. He returns with a doctor from the sanatorium; the youth has somehow managed to pull himself out, and is lying exhausted on a boulder, his leg smeared with blood. The autumn evening has come early in the valley and he has caught a cold. Once he has cleaned out his runny nose in the river, the doctor and an assistant take him back to the sanatorium, silhouetted in the twilight as they go, apparently restraining the youth with a rope (fig. 9).

Fig 9: Back to the sanatorium

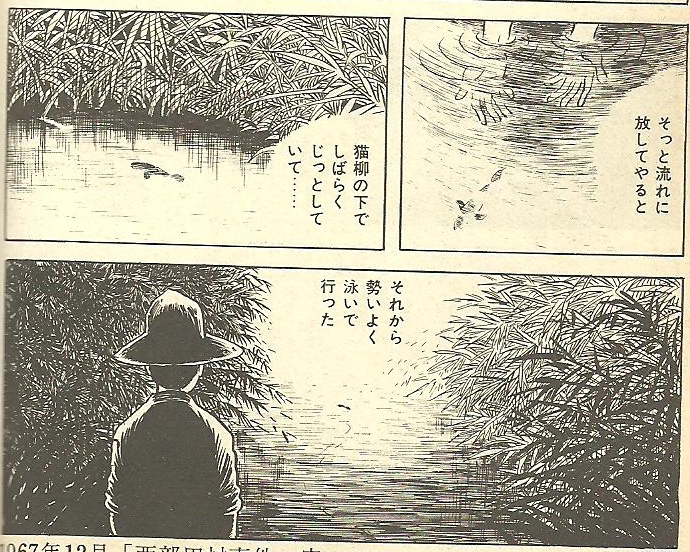

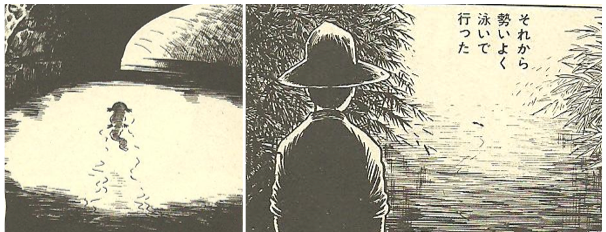

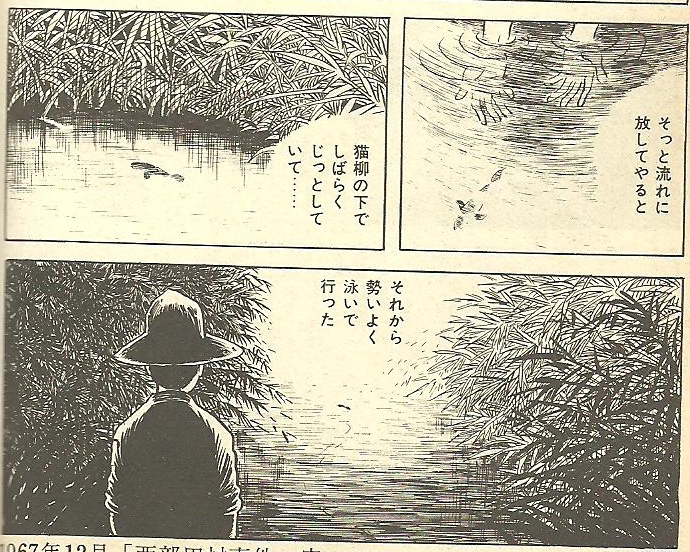

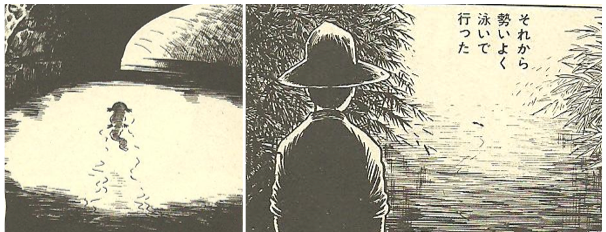

Hero stays behind for a reflective cigarette. “This incident that caused so much of a stir has been brought to a low-key denouement by this unexpected accident,” he reflects, in strangely stilted manner. Then he thinks of the fish that had been trapped under the escapee’s foot. It is still alive, though limp and moribund. He picks it out of the hole and returns it to the river (fig. 10 top right). It rests for a while in the shade of the pussy willow (fig. 10 top left), then swims away powerfully. The final frame shows it disappearing into light while hero is seen from behind, in shadow, watching it go (fig. 10 bottom).

Fig. 10

Like many of Tsuge’s works in this period, ‘The Incident at Nishibeta Village’ has the quality of a fable. On the face of it this is a mild, humorous story – a whimsical yarn with a bit of slapstick comedy, slightly reminiscent of an early Jacques Tati film perhaps. It only gently hints at concealed depths. Shin Gondô, who played Boswell to Tsuge’s Johnson in publishing an 800-page collection of interviews with him, remarks: “There’s a fair bit of slapstick comedy along the way, and it’s not a particularly dark story, but there’s a strangely lonely feeling about the way it ends” (Tsuge and Gondô 1993(2): 95). I would agree. So let us now consider where that lonely feeling comes from.

The story obviously invites us to draw some kind of parallel between the trapped fish and the youth confined in the sanatorium. Indeed, Tsuge himself has stated “I matched the youth and the little fish as doubles. They were both stuck in little holes and swam away lustily. I like to draw in a way that leaves a lingering reverberation” (ibid. 96). At the end of the incident, both the youth and the fish are in a totally exhausted state, and Tsuge uses the same word, guttari (dead tired) to describe both. The youth seems perfectly normal, if very slightly eccentric. The fish is very literally oppressed, by a foot crushing down on it. At the end of the yarn, the fish swims free – liberated, ironically, by a fisherman – while the apparently normal youth is escorted back to captivity. I would argue that here is a gentle, implied criticism of Japan’s mental health system.

Bear in mind that the concept of a perfectly sane person being forcibly incarcerated in a small rural sanatorium is particularly plausible in Japan, which has the world’s highest per-capita mental hospital population, with a relatively small number of psychiatrists to look after them – 206 mental hospital beds but only 9 psychiatrists per 100,000 population, compared to 31 beds and 14 psychiatrists per 100,000 in the US, [4]. leading to a heavy reliance on physical restraint and chemical sedatives. Japan never went through the process of closing down mental hospitals and casting out patients – a process known euphemistically as ‘mainstreaming’ in Reagan’s USA and as ‘care in the community’ in Thatcher’s Britain. Instead mental hospitals – most of them private, many of them set up with government encouragement after World War II when defeat in war had left deep psychological scars and the government had no cash to deal with them – have remained numerous and they are a powerful, well-organized lobby. The result is that it is only too easy to get forcibly incarcerated in Japan – all it takes is two signatures, one from a psychiatrist who may be in charge of the institution expecting to take custody (and profit materially), and the other from a relative, typically one’s own spouse, parent or child. The risks of abuse in such a system are obvious, especially when many of the institutions are small and in remote rural locations, like the one at Nishibeta-mura.

Not that Tsuge comes at us waving a banner about this serious social problem. The tone is muted – a harmless youth with an interest in fishing, and a posse of villagers who are depicted as comical bumpkins, but who nonetheless are willing to consider killing the fugitive. The world’s most frequently quoted Japanese proverb is “the nail that sticks out gets hammered down” (deru kui ga utareru). In other words, Japanese society can come down hard on the eccentric or non-conformist. Tsuge, himself a perennial outsider, no doubt had this kind of thing in mind when he drew this manga, with its dramatic contrast between the dangerous fugitive described by the villagers, and the weak bespectacled youth he turns out to be.

But the fish imagery also works at a deeper level, as we shall see if we go back to the manga Tsuge published immediately before this one – ‘Akai Hana’/Red Flowers.

Fig. 11 ‘Nishibeta’ (left), ‘Akai Hana’ (right)

There is a clear visual parallel between the fugitive youth in ‘Nishibeta,’ and the young girl, named as Sayoko Kikuchi, in ‘Akai Hana.’ Each lies exhausted by the side of the river (fig. 11). Her exhaustion is brought on by menstruation – possibly her first ever – symbolized by red flowers falling onto a river. His exhaustion, likewise, hints at a sexual explanation. When he shoved his foot into the watery hole, that was a kind of spastic penetration – possibly his first ever. His foot was caught, as by a vagina dentate. The struggle to get out has left him lying there like a fish out of water. Freudian critic Masashi Shimizu, who devoted 20 pages to ‘Nishibeta’ in his monumental study of Tsuge (Shimizu 2003) follows that line up to the point where the youth gets his leg stuck, but then argues that the injury to the leg signifies the father figure, represented by the huge boulder where all this happens, punishing the youth for trying to get back to the womb through incestuous penetration, with a threat of castration. The exhaustion and bloody leg are left over from that struggle (Shimizu 2003: 390). As for the little fish, that represents a fetus, one that has succeeded in staying in the womb. When the fisherman lets it go at the end of the story, he is reluctantly admitting the need to get out of the womb and join the river of life. Shimizu further argues that the youth is a subsection of the fisherman’s own personality, so that the entire story is a projection of the fisherman’s own internal psychological state. The fact that the fisherman has to walk round the perimeter of the sanatorium grounds, and presumably will have to do so again on his way home, indicates that he is in a borderline condition between sanity and insanity himself (ibid. 391). When he returns the fish to the river, he is coming back from the brink of the escaped youth’s insanity, which is in fact no more than a rash attempt to do what all men really want to do – return to the womb.

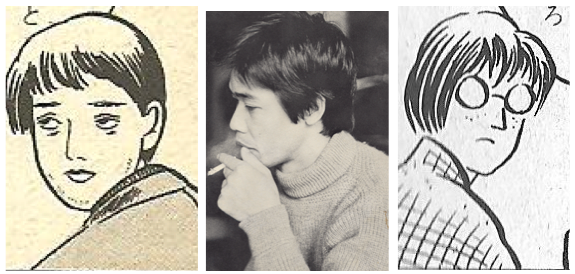

Shimizu’s interpretation is partially persuasive, and I am willing to accept that both the fisherman and the youth represent aspects of Tsuge’s own personality. The fisherman is clearly a version of Tsuge, who we know loved his rural rambles and fishing trips. But in terms of physical appearance it is the escaped youth who more closely resembles Tsuge, as we can see from fig. 12. Nearly all Tsuge’s mature works include a character closely based on himself. Usually he has some function close to that of a narrator, often in the role of a traveler arriving in unfamiliar territory, as here. A year or two later Tsuge started to draw this character so that it bore a physical resemblance to himself, as in the 1970 image on the left from ‘Yanagiya Shujin’. The photo of Tsuge (fig. 12 center) is from roughly this period. But in ‘Nishibeta,’ as in ‘Akai Hana’ and the subsequent ‘Mokkoriya no Shôjo’ (another offbeat tale of a rural fishing trip) the traveler has a plain, button-nosed face. Instead, it is the escaped lunatic who makes us think we might be looking at Tsuge himself, or some version of him, behind his blank, round spectacles (right).

Fig. 12 ‘Yanagiya Shujin’ (left), photo of Tsuge (center), ‘Nishibeta’ (right)

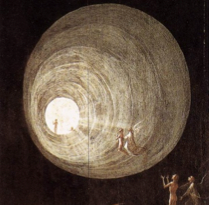

But I would argue that Shimizu does not fully acknowledge the attenuated, shadowy relationship of the surface story to the underlying Freudian/Rankian myth. There are no women at all in this story, unlike many other Tsuge manga that do turn on sexual encounters, and the symbolism has drifted far, far away from anything resembling a real human experience. As father figures go, large boulders are open to question. The youth accidentally gets his foot trapped in the hole – there is no intentionality. But the biggest problem with the Oedipal reading concerns the little fish. It is not happy to be back in the womb, if the little hole is serving that function – it is trapped. I would argue that it has another symbolic role, representing the trapped human spirit. When it swims away in the final frame, we feel the same kind of liberation as at the end of ‘Sanshôuo’ (Salamander), published six months earlier in Garo. That story is narrated by a salamander swimming in a sea of sewage underneath some great city. The salamander finally swims into the distance, remarking “I wonder what will come floating my way tomorrow. Thinking about it brings me a feeling of incredible pleasure.” Tsuge’s final frames are always very significant, and the final frame of Nishibeta is clearly designed to echo that of Sanshôuo (fig. 13). Here the observer is saying “with that, it swam vigorously away.”

Fig. 13 ‘Sanshôuo’ (Salamander), final frame (detail) left; Nishibeta final frame (detail), right

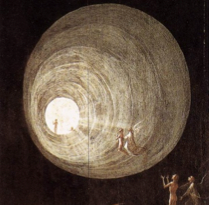

What are we to make of these two similar yet contrasting images of aquatic animals swimming into the distance? Both are bathed in an ethereal light and swimming towards more light, possibly signifying enlightenment, escape, or death/rebirth, as in many accounts of Near Death Experience and Hieronymus Bosch’s famous painting, The Ascent of the Blessed (fig. 14). ‘Sanshôuo’ is Tsuge’s only cartoon with no human characters in it. The phallic salamander represents both the body and spirit of a man. In ‘Nishibeta,’ the fish has swum further into the distance, observed by a real man. We sense a Descartian distinction between body and soul here: and if the little fish is the human spirit, then does its departure imply the death of the human body? For me, the answer is yes. The departure of the little fish hints at the death, not of the traveler but of the youth from the sanatorium. Perhaps he will finally free himself through suicide. Or perhaps his traumatic experiences will make him really go mad, so that the spirit leaves the body in another sense.

Fig. 14 Hieronymus Bosch, The Ascent of the Blessed (detail)

Fish and other aquatic animals make many appearances in Tsuge’s work. The fish can do a lot of symbolic work: its shape and its little fins make it a purposeful symbol, always swimming in a clear direction. At the same time it is liable to be swept along by strong currents once it ventures forth from a womb-like pond or backwater, making it serve as an apt metaphor for the human condition. And those little fins can indeed hint at the not-yet-developed limbs of a human fetus.

I hope this short paper has given some idea of the complexity of symbolism in the works of Yoshiharu Tsuge. For him, meaning is diffused to the point where it becomes emotion. That may sound silly, but I do feel that the complex symbolic system behind this seemingly simple tale perhaps accounts for the feeling of resignation and calm that comes over us as we view its final frame, the “loneliness” (sabishisa) mentioned by Gondô. Tsuge says he worked hard to produce that effect. Normally modest to a fault, he allows himself a note of pride in the way he made the little fish not just swim away, but pause for a moment, motionless under the pussy willow. It is a moment that reminds us that freedom includes the freedom to stay, as well as to go; and perhaps, to stay alive, as well as to die. “I thought that was quite a good scene within the fantasy,” he admits (Tsuge and Gondô 1993(2): 95-6). This leads to the discussion quoted earlier, about trying to leave a “lingering reverberation.” That is my translation of the Japanese word yo’in, and it is a key term for understanding Tsuge. His tales are not secretly coded narratives with a one-to-one identity between surface narrative signifier and psychosexual signified, as Shimizu would have us believe. Rather they are deliberately diffuse and ambiguous, not crossword puzzles but kôans, stories put out there to invite the reader to think, to seek for meaning. We will never come to the definitive interpretation, for there is no such thing, but we can still enjoy the quest.

____________________

[1]There are also very poorly translated ‘scanlations’ of ‘Numa’ (Marsh) and ‘Chiko’ (Chico) floating around the internet. His works are readily available in Japanese, and all the ones discussed here are included in Tsuge 1994a or Tsuge 1994b, each of which is a handy paperback currently available at Amazon Japan for 610 yen, or about $7. [back]

[2]Note the teasing shape of what appears to be smoke rising from a bonfire on the left, perhaps suggesting a peacock or phoenix stooping down to peck. [back]

[3] All translations of Japanese works by Gill. [back]

[4] Entries for Japan and the US in Mental Health Atlas 2005. World Health Organization. Dept. of Mental Health and Substance Abuse. [back]

REFERENCES

Gravett, Paul. 2004. Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics. London: Laurence King Publishing.

Marechal, Beatrice. 2005. “On Top of the Mountain: The Influential Manga of Yoshiharu Tsuge.” In The Comics Journal, Special Edition (2005), 22-28.

Ng, Suat Tong. 2010. ‘Yoshiharu Tsuge’s Red Flowers’ Available at . Accessed January 30, 2011.

Schodt, Frederick. 1996. Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press.

Shimizu, Masashi. 2003. Tsuge Yoshiharu o Yome (Read Yoshiharu Tsuge!). Tokyo: Chôreisha.

Tsuge, Yoshiharu. 1985. ‘Red Flowers’ (translation of ‘Akai hana,’ 1967). In Raw vol. 1 #7. New York: Raw Books.

Tsuge, Yoshiharu. 1990. ‘Oba’s Electroplate Factory’ (translation of ‘Oba Denki Mekki Kôgyôsho,’ 1973), in Raw vol. 2 #2. New York: Penguin Books.

Tsuge, Yoshiharu. 1994a. Akai Hana (Red Flowers). Tokyo: Shôgakkan. In Japanese.

Tsuge, Yoshiharu. 1994b. Neji-shiki (Screw-style). Tokyo: Shôgakkan. In Japanese.

Tsuge, Yoshiharu. 2003. ‘Screw-Style’ (translation of ‘Neji-shiki,’ 1968). In The Comics Journal #250. Seattle: Fantagraphics.

Tsuge, Yoshiharu. 2004. L’Homme sans talent (translation of Munô no Hito, 1984-85). Angoulême: Ego comme X. In French.

Tsuge, Yoshiharu and Shin Gondô. 1993. Tsuge Yoshiharu Manga-jutsu (The Manga Art of Yoshiharu Tsuge). Tokyo: Wise Shuppan. 2 volumes. In Japanese.