My wife has been trying to get our daughter to read Jane Austen since our daughter started middle school. She’s now a senior, and when faced with a summer reading list for A.P. English, she picked Pride and Prejudice because her teacher said he didn’t like it. She can be perverse that way, but her impish impulse backfired because then she couldn’t stop reading the entire six-novel Austen oeuvre (plus the incomplete Sanditon even though she can’t bear not knowing how a romance plot ends).

I theoretically read Emma in college, and I have an increasingly thin memory of Northanger Abby from grad school, but my wife gasped—Yes! Gasped, I say!—when I admitted at our dinner table that I had in fact never read Pride and Prejudice. The characters in Karen Joy Fowler’s The Jane Austen Book Club give the same reaction when the lone male in the club makes the same admission.

I’m teaching Fowler’s novel this semester as part of my New North American Fiction course, AKA “Thrilling Tales.,” so I’m braced for more gasps.

I stole the subtitle from the issue of McSweeney’s that Michael Chabon edited back in 2002. His pulp-reclamation project includes a range of highbrow authors writing in lowbrow genres: horror, scifi, mystery, but not—I only recently noted—romance. Same is true of the issue of Conjunctions Peter Straub guest-edited the same year. So the proud gatekeepers of 21st century literature were allowing in zombie ghosts and steampunk Martians, but no tales with “Reader, I married him” closure.

I theorized the prejudice was against formula: any narrative with a predetermined ending is by definition formulaic, and so not literary. And though I think that’s largely true, the prejudice runs deeper.

My daughter told me I had to read Pride and Prejudice to avoid humiliation in my own classroom. My students will have read it, she said, and since Fowler’s novel references it so deeply, and since it’s considered the best of Austen’s novels, and one of the best novels of English literature, I agreed I had no choice. This implies I was resistant. I wasn’t. Fowler’s novel is brilliant (easily the most engaging metafiction I’ve ever read), and I had every intention of enjoying Austen too.

And yet why did I hesitate? And why hadn’t I included a work of romance in my Thrilling Tales syllabus the first time I taught the course? I’d covered so many other genre bases—time travel, superheroes, genetic engineering, vampires. It turns out the diagnosis isn’t all that complicated.

When I had a doctor’s appointment over the summer, I took the library copy of Pride and Prejudice that my daughter had read. The nurse (female) said, “Oh, what a good book.” The doctor (male) said, “Oh god, that thing.” He’d read it in his A.P. English class back in high school. I don’t know when the nurse read it, but I assume it was for pleasure. Non-literary female pleasure, the kind even the omnivorous Chabon and Straub couldn’t get there lowbrow brains around. 1930s space aliens is one thing, but Harlequin Romances? Please.

But what genre doesn’t suffer from bad examples? I’ve read some cringingly embarrassing sonnets, but they don’t reveal anything about the merits of 14-line rhyme structures. The best Shakespearean sonnet doesn’t reveal anything innately excellent about the form either. It’s just a form. And Shakespeare knew how to write in it.

Few authors are regarded as their genre’s best practitioners. Even fewer are regarded as inventors of their genres. Ursula Le Guin (for example) falls into the first category, but not the second. Jerry Siegel, the co-creator of Superman, falls into the second category, but not the first. If you consider a Shakespearean sonnet its own genre, then Shakespeare falls into both. So does Jane Austen.

I’m looking forward to discussing The Jane Austen Book Club with my class soon, but first a superheroic revelation of my own: Without Pride and Prejudice, my favorite 1930s space alien, Superman, would not exist. Jane Austen is Jerry Siegel’s secret collaborator, and without her, the comic book genre that followed Action Comics No. 1 wouldn’t exist either.

To the best of my knowledge, no one has ever drawn an Austen-Superman connection. But the line of influence is direct. It’s called The Scarlet Pimpernel. The novel was published by Baroness Orczy in 1904 and is one of the most influential texts for early superheroes. Its title character is often cited as the first dual-identity hero and the inspiration for Zorro and dozens of other pulp do-gooders culminating in Batman and Superman. Siegel was a Pimpernel fan and reviewed one of Orczy’s sequels in his high school newspaper. Take away Orczy’s mild-mannered Sir Percy and the mild-mannered Clark Kent vanishes too.

The Scarlet Pimpernel is also a romance, one that formulaically matches Pride and Prejudice. It’s told from the perspective of its female protagonist, Marguerite, who, like Austen’s Elizabeth, is blind to the true character of the novel’s hero. Elizabeth thinks Mr. Darcy is an arrogant jerk. Marguerite thinks Sir Percy is a cowardly fool. Or they do for the first halves of their novels, because after a pivotal middle scene (Mr. Darcy proposes, Marguerite confesses), the second halves are spent revealing Darcy’s and Percy’s secret heroism. Austen uses the word “disguise,” Orczy prefers “mask,” but both metaphors must be removed.

That also requires some suffering, since Elizabeth and Marguerite must recognize their mistakes in order to be united with their heroes. Austen says “humbled.” Orczy says, “the elegant and fashionable [Marguerite], who had dazzled London society with her beauty, her wit and her extravagances, presented a very pathetic picture of tired-out, suffering womanhood.” Unmasked hero and humbled heroine may now live happily everafter.

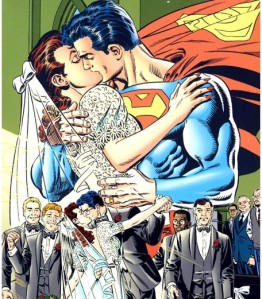

Jerry Siegel adopted the Austen-Orczy formula too. As long as Lois Lane can’t see through Clark’s disguise, she can’t be united with her Superman. But Austen mostly and Orczy entirely limit their perspectives to their heroines’ points of view. Siegel sticks with his hero. When Joe Shuster draws Clark changing into Superman, readers witness the unmasking, but Lois doesn’t. She’s stuck in the first half of Elizabeth’s and Marguerite’s plotline. Austen’s and Orczy’s readers learn with their heroines, but Superman readers can already see Lois’ mistake. Shuster even draws Clark laughing behind her back. She is “humbled,” but she can’t learn from it and so can’t be united with her would-be lover. The romance plot is frozen.

Siegel did try to reach the second half of Pride and Prejudice though—perhaps as a result of having reached marital closure himself. In 1940, two years into writing Superman, and two months into his own marriage, he submitted a script in which Superman unmasks to Lois.

LOIS: “Why didn’t you ever tell me who you really are?”

SUPERMAN: “Because if people were to learn my true identity, it would hamper me in my mission to save humanity.”

LOIS: “Your attitude of cowardliness as Clark Kent—it was just a screen to keep the world from learning who you really are! But there’s one thing I must know: was your—er—affection for me, in your role as Clark Kent, also a pretense?”

SUPERMAN: “THAT was the genuine article, Lois!”

The revelation completes the Austen formula. When Darcy tells Elizabeth, “You taught me a lesson, hard indeed at first, but most advantageous. By you I was properly humbled,” the two can unite because now they are on the same plane. Superman comes to his “momentous decision” after Siegel introduces the superpower-stripping “K-Metal from Krypton,” the only substance that can humble the Man of Steel.

But the story was rejected. An editor wrote in the margin: “It is not a good idea to let others in on the secret.” It would have run in Action Comics No. 20. Instead, Clark reveals himself to Lois in No. 662, fifty years later. They married in 1996, the year Jerry Siegel died.