Jaime Hernandez’s “Browntown” has been lauded by everyone from Tom Spurgeon to Jeet Heer, the later of whom states that it is “arguably one of the best comics stories ever”.

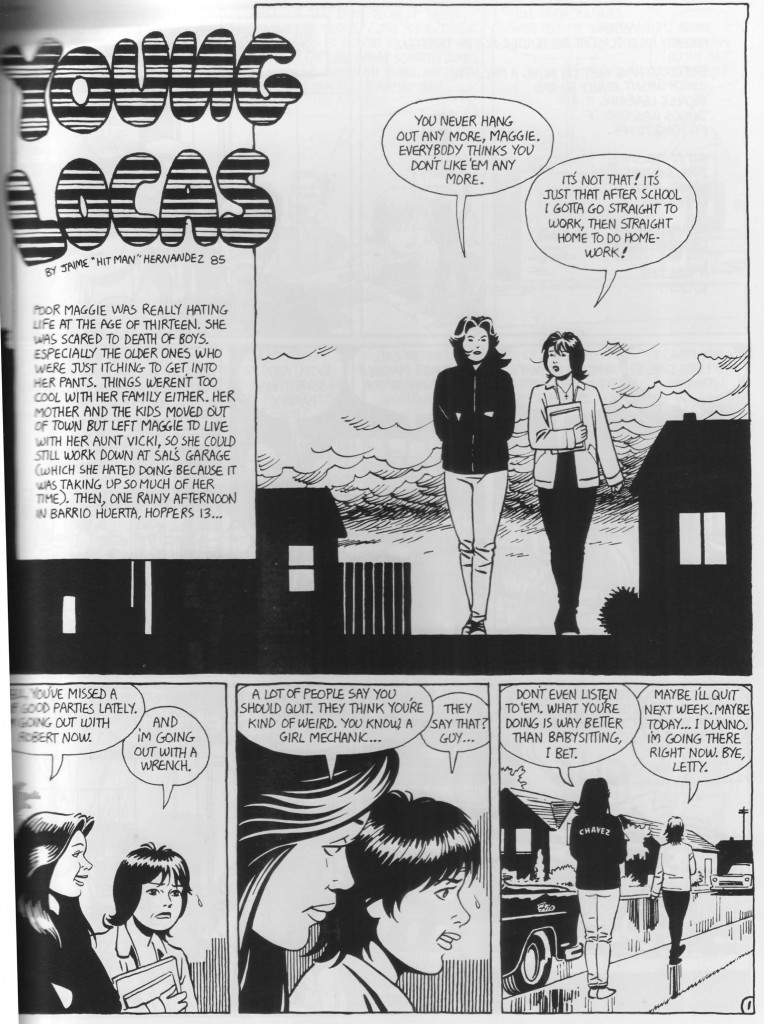

It’s a bit of a let-down, then, to actually read the thing and discover a decent but by no means revelatory, piece of program fiction. All the hallmarks are there: the precocious child narrator as guarantor of authenticity; the ethnic milieu as guarantor of authenticity; the sordidness as guarantor of authenticity and the trauma as guarantor of authenticity. Poignant ironies fall upon the narrative with a sodden regularity, till the only landscape that can be seen is the wet, heavy drifts of meaning.

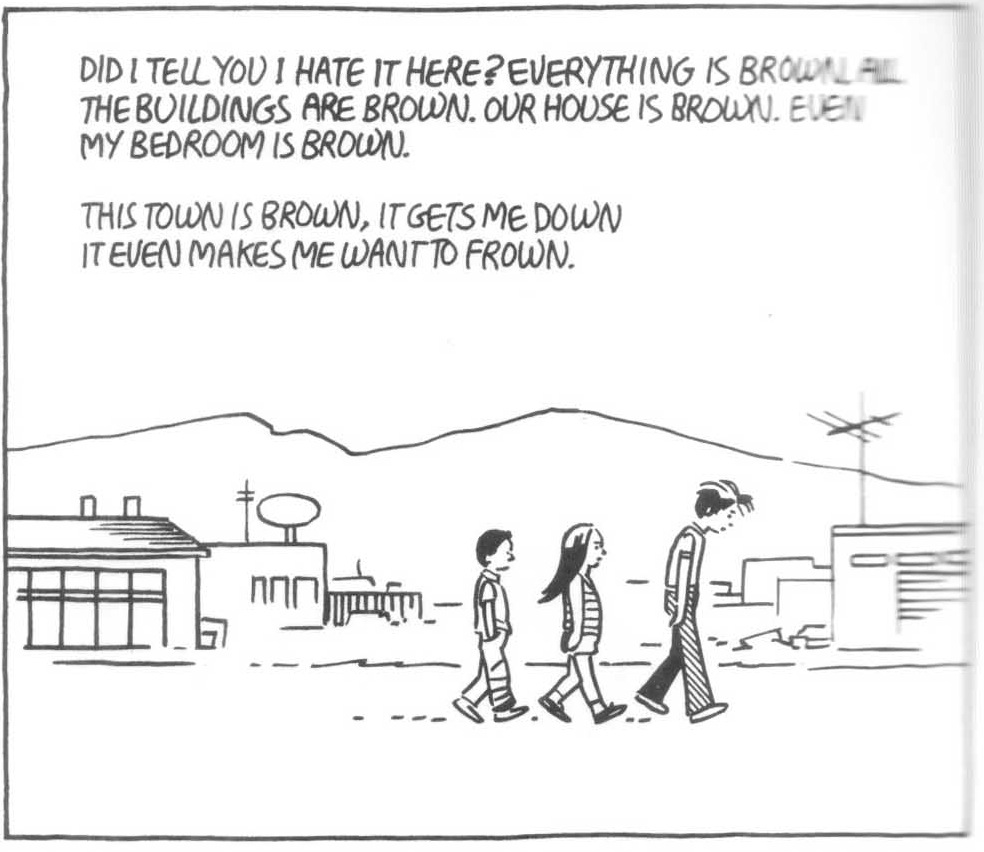

For what it is, “Browntown” isn’t terrible. Jaime’s precocious child narrator is endearing

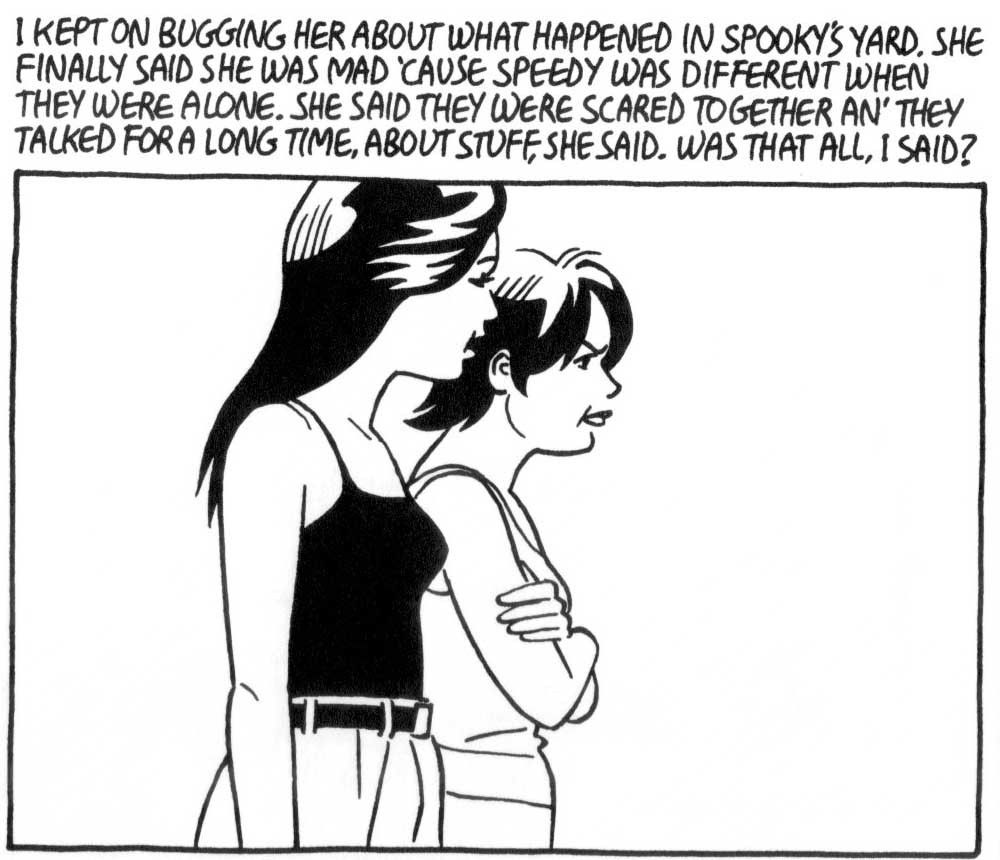

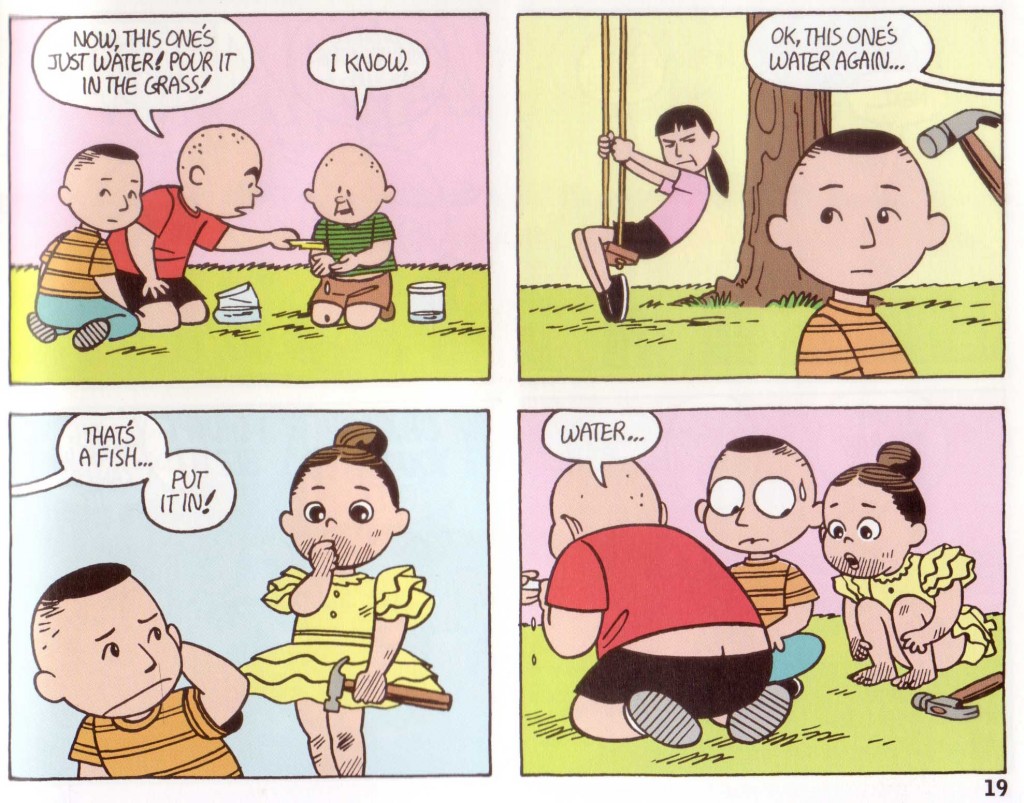

his ethnic milieu is surprisingly uninsistent and unforced; his traumas are doled out with a disarming lightness — as when Calvin’s years of abuse are limned in the space between panels:

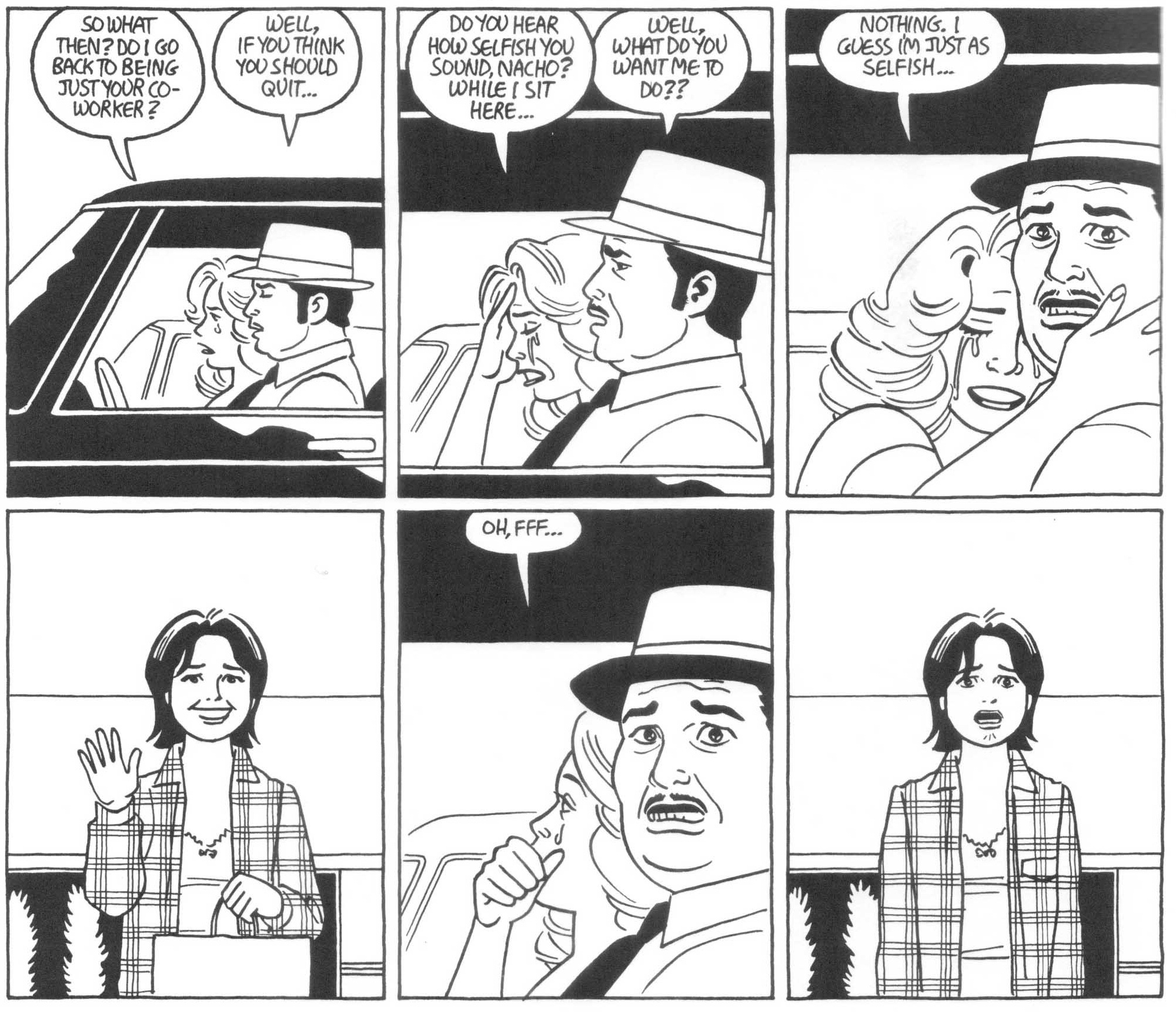

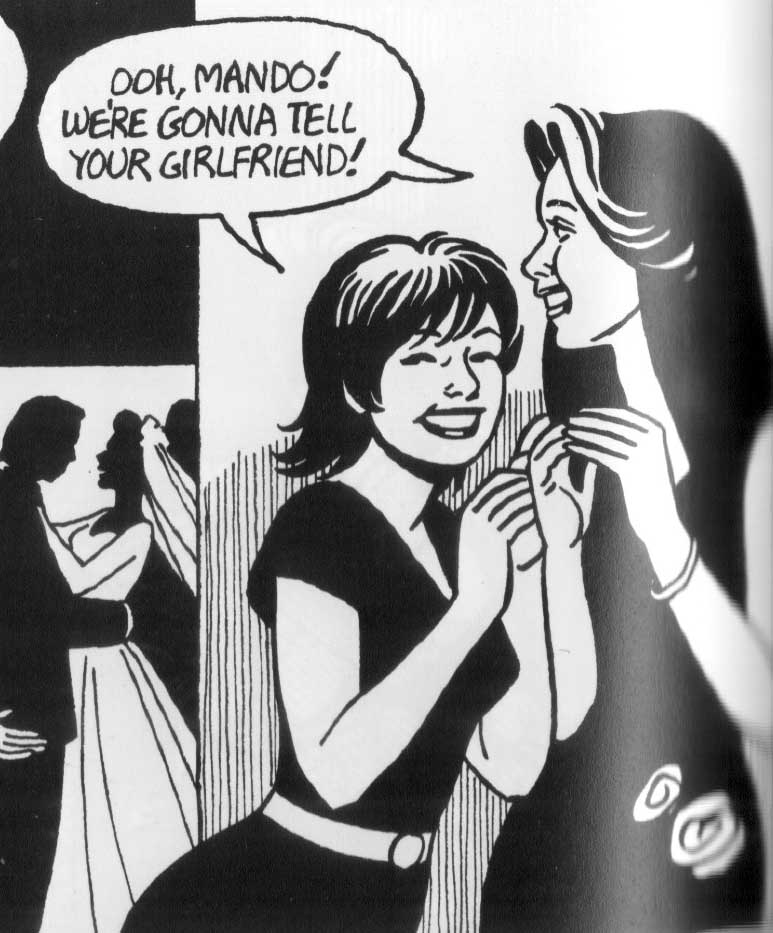

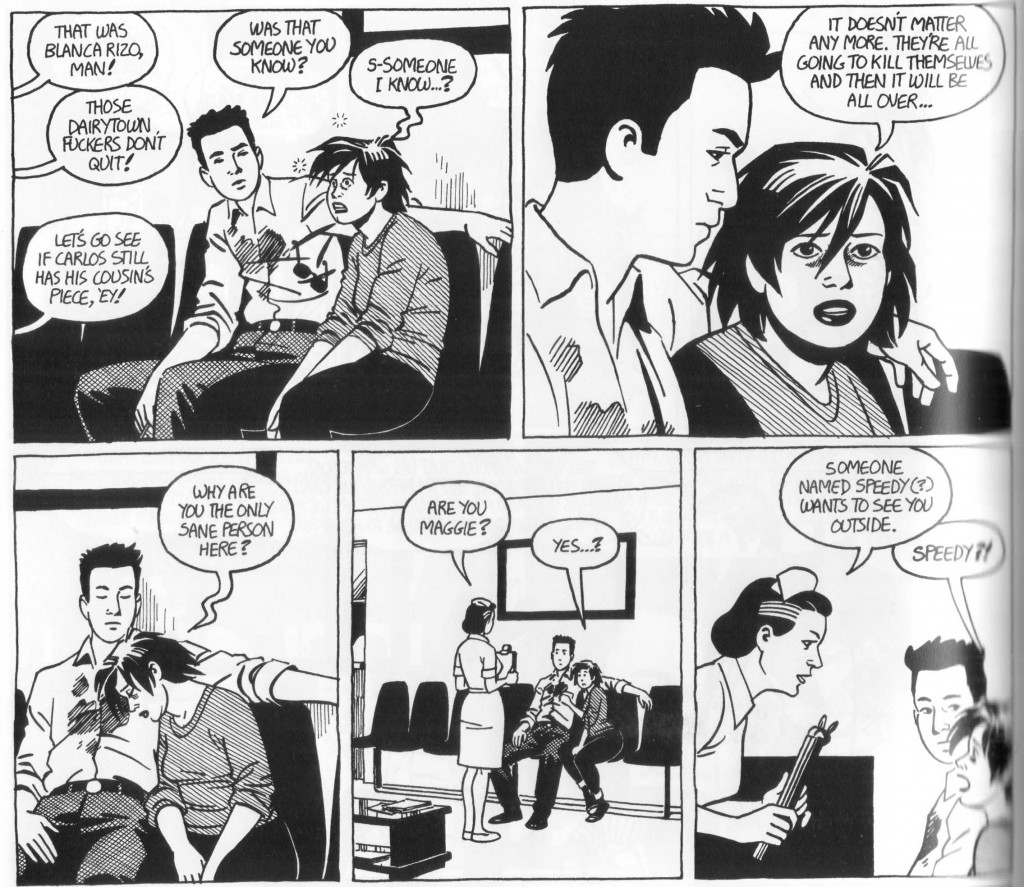

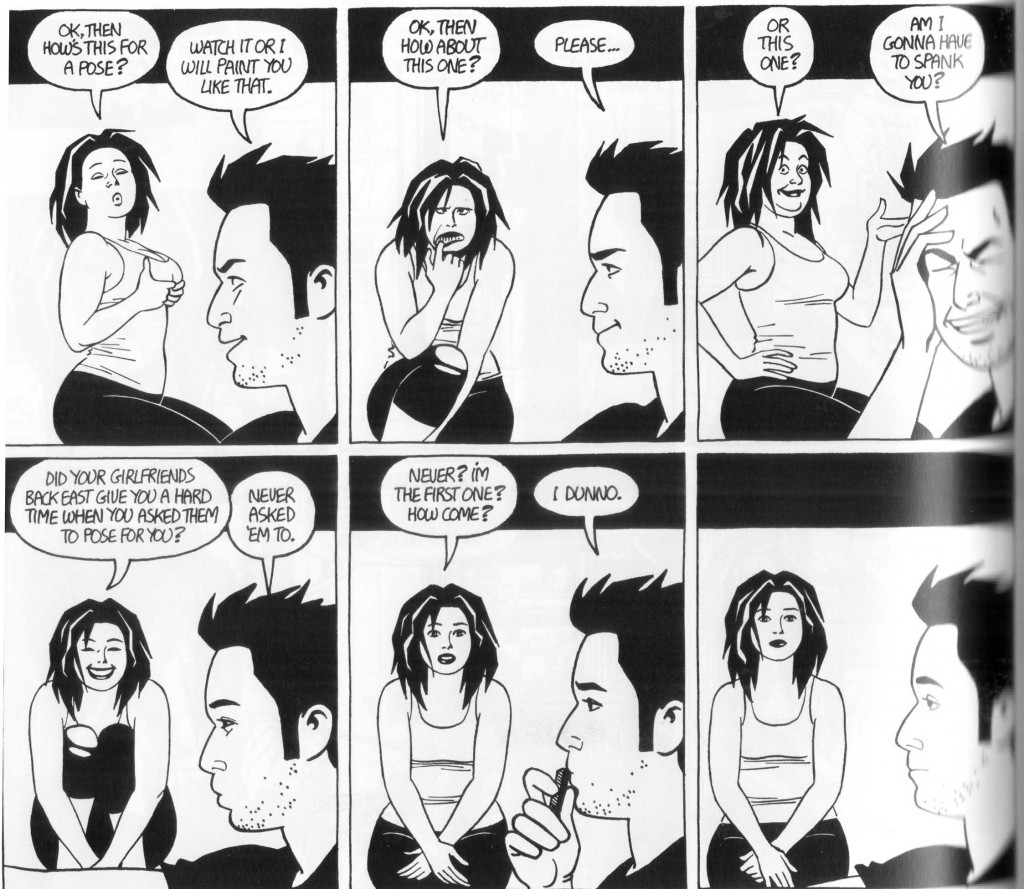

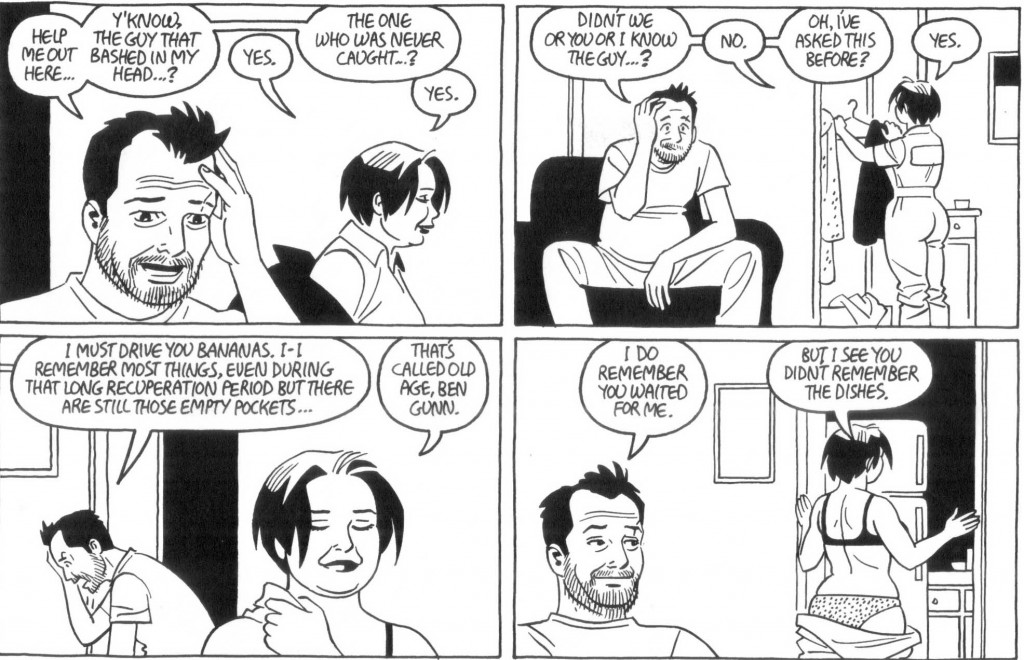

But still; there’s nothing particularly brilliant here, either in the use of language, or in the drawing, or in the use of the comics medium. In this sequence, for example, Jaime uses a series of verbal and visual clichés to present the end of an affair.

“Nothing, I guess I’m just selfish,” she says, as the stylized tears pour down. The camera moves closer, and then we’ve got a shot/reverse/shot. Entirely competent story-telling, sure. Masterpiece by one of the genre’s greatest creators? For goodness’ sake, why?

_________________________________________________

I read a fair bit of the Locas stories for this post — Death of Speedy, The Education of Hopey Glass, The Love Bunglers, bits and pieces of other stories, including Wig Wam Bam. I haven’t exactly grown more fond of Jaime’s work, but I think I have a better sense of what I’m supposed to like about it.

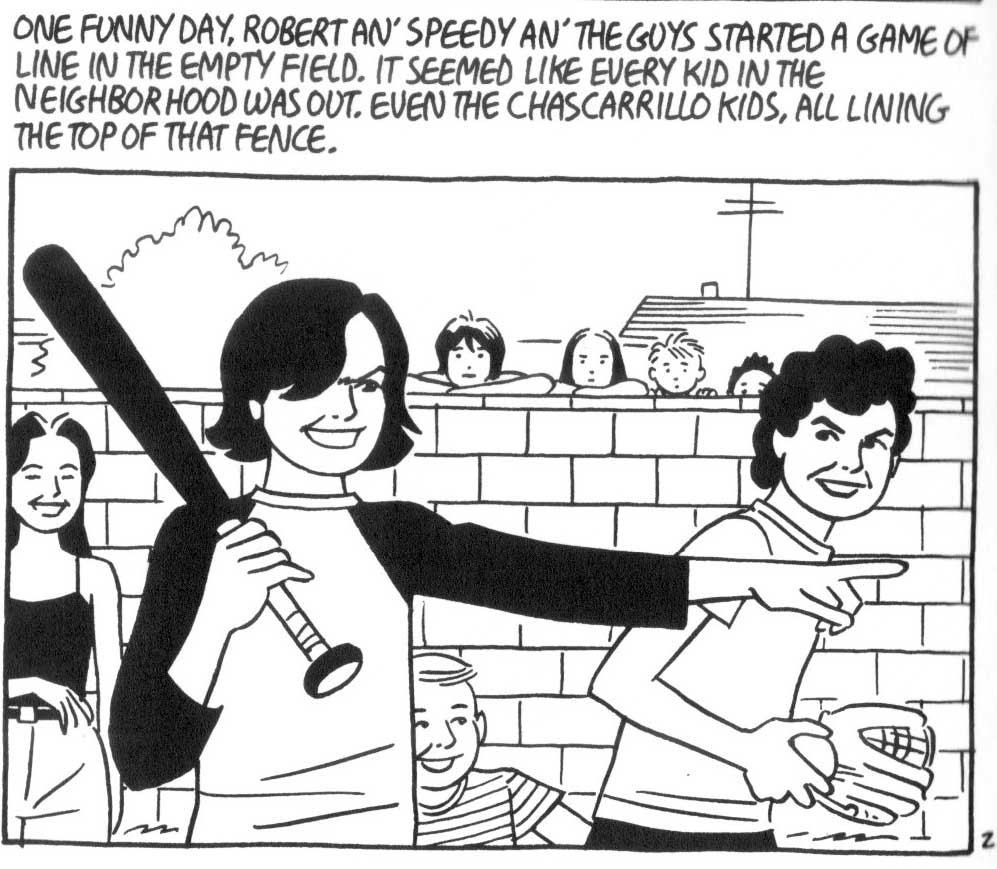

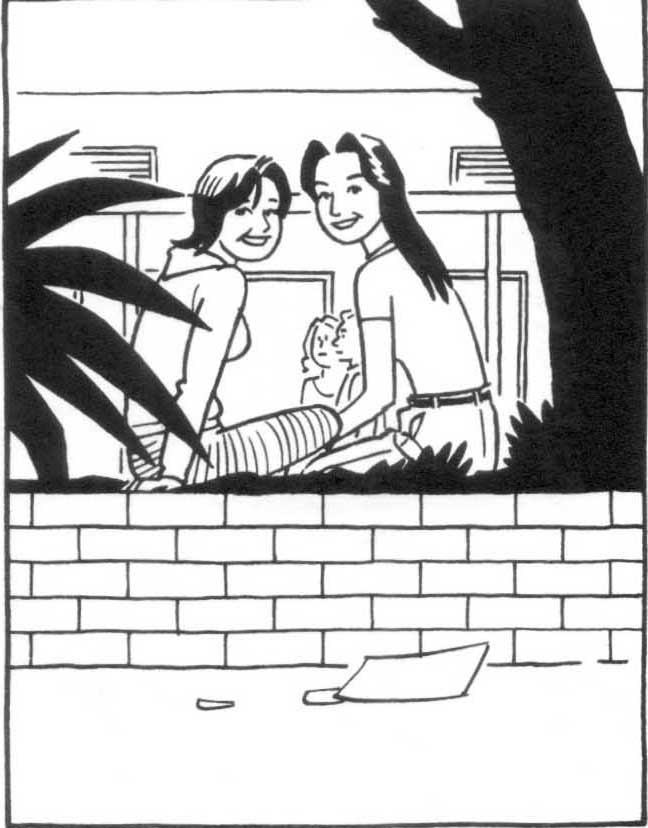

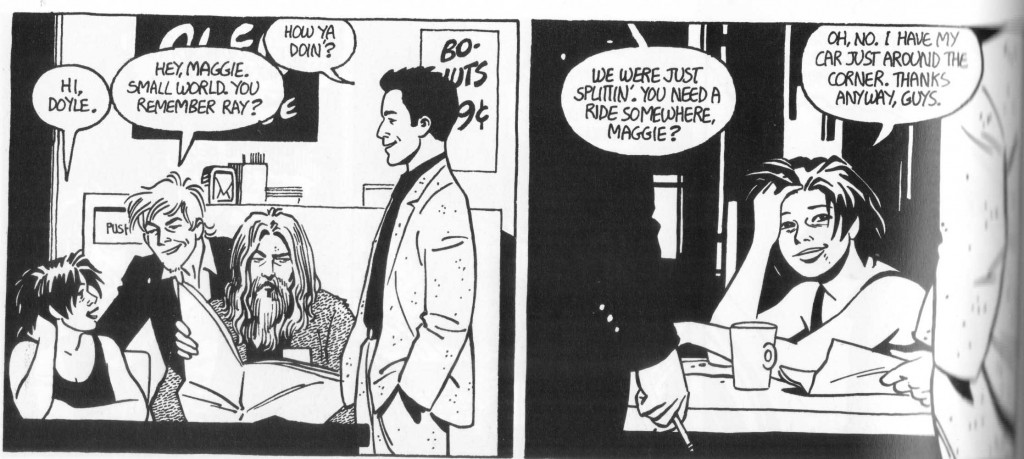

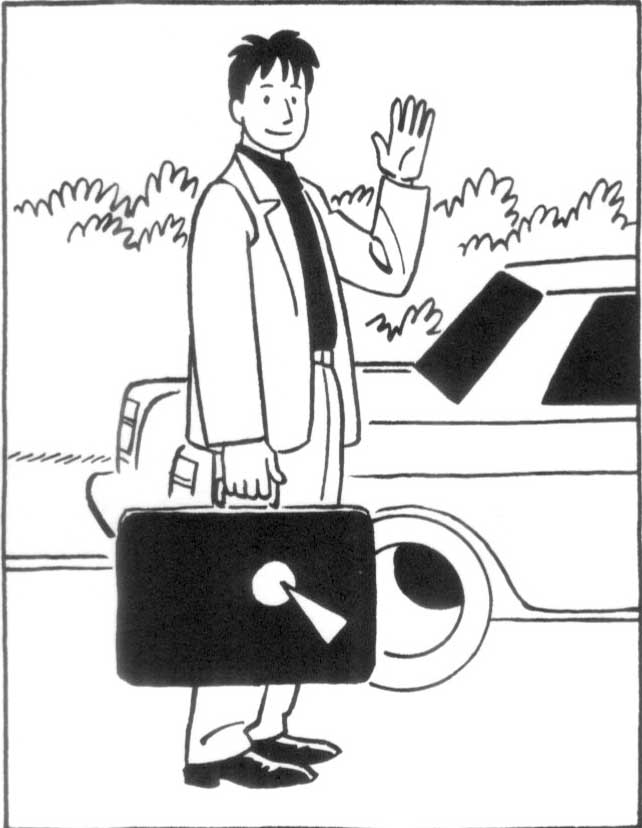

Which would be nostalgia. The difference between “Browntown” and an anonymous short story in a lit magazine isn’t Jaime’s skill, or his handling of plot or theme or character — none of which, as far as I can tell, rise above the pedestrian. Rather, “Browntown” is different not because of what’s in it, but because of what’s outside it: the years and years of investment in the characters, by both the author and his readers. Here, for example:

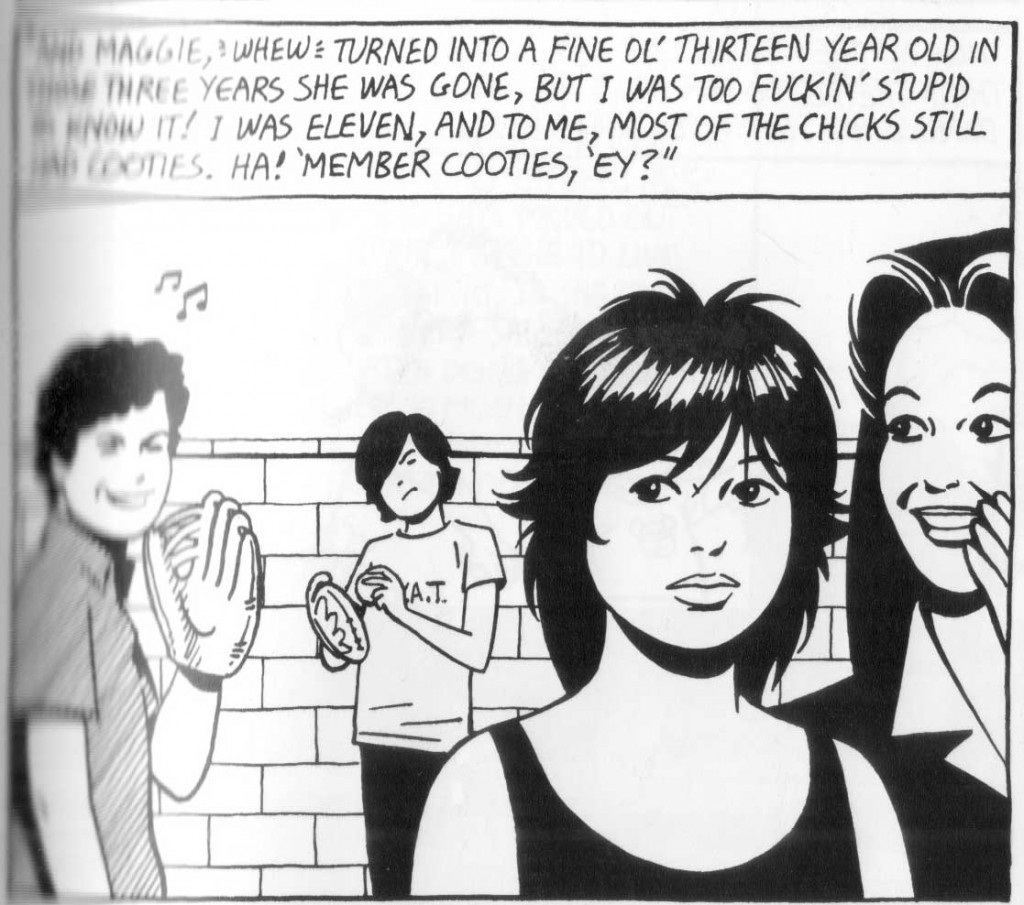

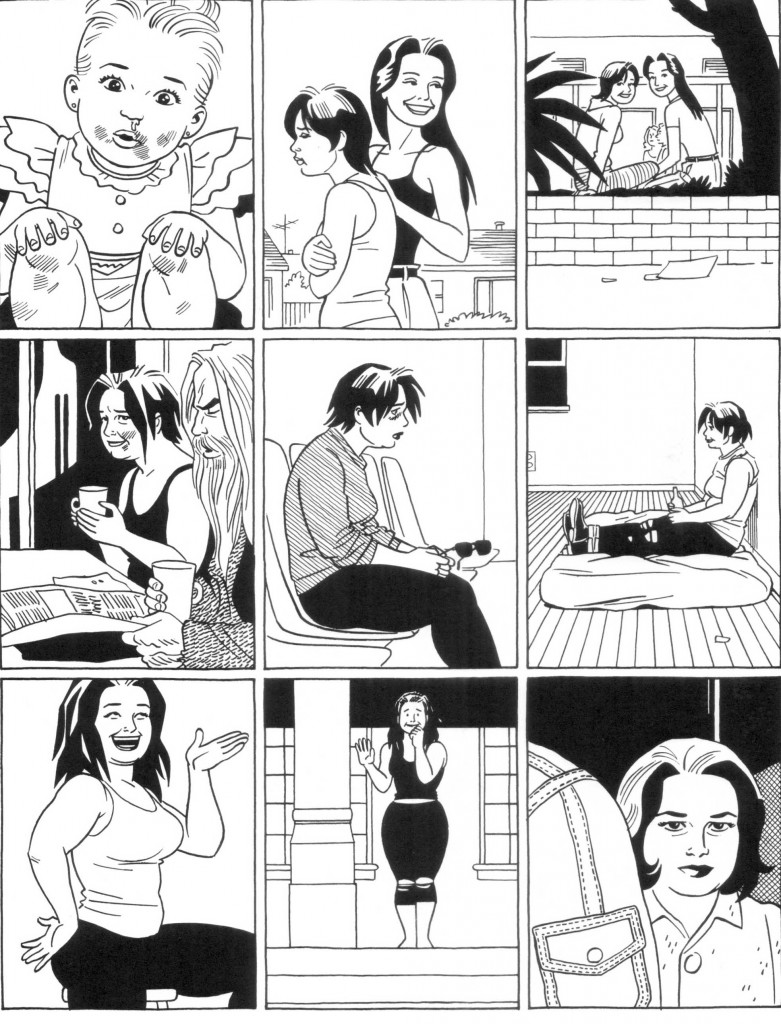

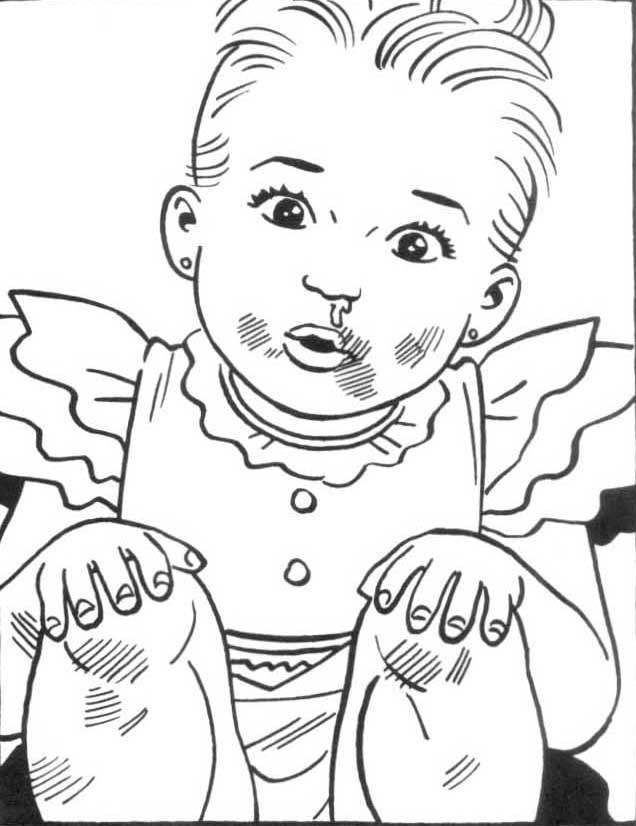

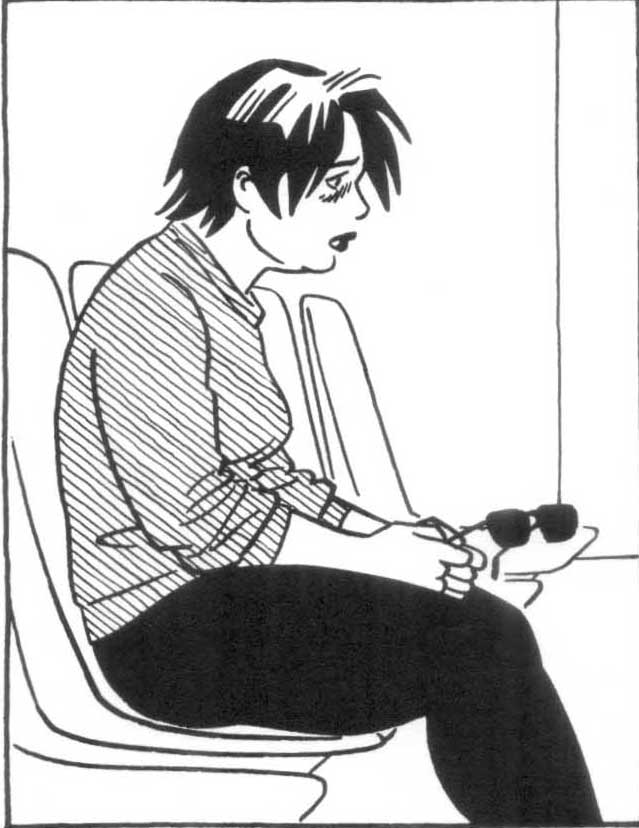

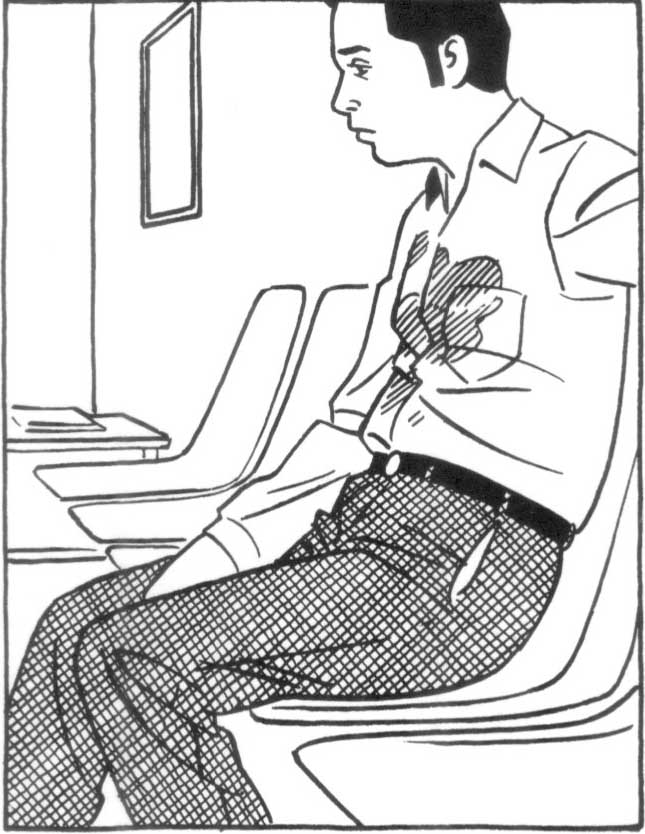

You see Maggie from a distance, and then in close up. It’s not an especially interesting or involving visual sequence…except that this is the first time in the story that Maggie appears as an adolescent, thirteen years old and post-puberty. For those who have followed Jaime’s work (or even just read the first installment of the Love Bunglers that precedes this piece in Love and Rockets 3), that face is finally, recognizably, the Maggie we know (or one of the Maggies we know). As a result, there’s a charge there of recognition and delight. It’s analogous, perhaps, to Lacan’s description of the mirror stage:

This event can take place… from the age of six months, and its repetition has often made me reflect upon the startling spectacle of the infant in front of the mirror. Unable as yet to walk, or even to stand up, and held tightly as he is by some support, human or artificial…he nevertheless overcomes, in a flutter of jubilant activity, the obstructions of his support and, fixing his attitude in a slightly leaning-forward position, in order to hold it in his gaze, brings back an instantaneous aspect of the image….

We have only to understand the mirror stage as an identification , in the full sense that analysis gives to the term: namely, the transformation that takes place in the subject when he assumes an image – whose predestination to this phase-effect is sufficiently indicated by the use, in analytic theory, of the ancient term imago.

This jubilant assumption of his specular image by the child at the infans stage, still sunk in his motor incapacity and nursling dependence, would seem to exhibit in an exemplary situation the symbolic matrix in which the I is precipitated in a primordial form, before it is objectified in the dialectic of identification with the other, and before language restores to it, in the universal, its function as subject.

As always, Lacan is a fair piece from being comprehensible here…but in general outline, the point is that the child sees its image in the mirror — an image which is whole and coherent. The child identifies itself with this image, and so jubilantly experiences, or sees itself, as coherent and whole.

In her book Reading Lacan, Jane Gallop points out that the jubilation and excitement of the mirror stage is based upon temporal dislocation:

…in the mirror stage, the infant who has not yet mastered the upright posture and who is supported by either another person or some prosthetic device will, upon seeing herself in the mirror, “jubilantly assume” the upright position. She thus finds in the mirror image “already there,” a mastery that she will actually learn only later. The jubilation, the enthusiasm, is tied to the temporal dialectic by which she appears already to be what she will only later become.

Thus, there is a rush of pleasure in seeing the woman Maggie in the adolescent Maggie; the future image charges the past.

But the mirror stage is not just about recognizing the future in the present. It’s also about creating the past. Gallop explains that before the mirror stage, the self is incoherent; an unintegrated blob of body parts and non-specific polymorphous pleasures. But, Gallop continues, this is an illusion; the self cannot be an unintegrated blob before the mirror stage, because it is the mirror stage that creates the self. Thus:

The mirror stage would seem to come after “the body in bits and pieces” and organize them into unified image. But actually, that violently unorganized image only comes after the mirror stage so as to represent what came before.

The mirror stage, then, provides an image not just of the future, but of the past. The subject “assumes an image” not just of what she will be, but of what she was; the coherent image of the self is not just an aspiration, but a history. When Lacan says:

This jubilant assumption of his specular image by the child at the infans stage, still sunk in his motor incapacity and nursling dependence, would seem to exhibit in an exemplary situation the symbolic matrix in which the I is precipitated in a primordial form…

the specular image that is assumed is precisely the infans stage, and the I that is precipitated is precisely the primordial form. The jubilation is not just in seeing a future coherent self, but in seeing a past self that is coherent with both the present and future.

Or to put it another way, the attraction of nostalgia is not the idealization of the past, but simply the idea of the past — and of the future. It’s the romance of self-identity. Hence, nostalgia in the Locas stories isn’t a function of actual time (a reader who has in truth read for decades) so much as it is a projection of imagined history. How many times has Jaime drawn Maggie (or Perla, or Margaret, or…)? All of those images are a part of a self, snapshots of a connected chain of bodies linked from infancy to middle-age to (presumably) death. As Frank Santoro says in his piece about the Love Bunglers:

Something extraordinary happened when I read his stories in the new issue of Love and Rockets: New Stories no. 4. What happened was that I recalled the memory of reading “Death of Speedy” – when it was first published in 1988 – when I read the new issue now in 2011. Jaime directly references the story (with only two panels) in a beautiful two page spread in the new issue. So what happened was twenty three years of my own life folded together into one moment. Twenty three years in the life of Maggie and Ray folded together. The memory loop short circuited me. I put the book down and wept.

The power of the Locas stories, what makes them special, is not any one story, or instant, or image, but the knowledge of the whole — not in the sense that each part contributes to a greater thematic unity, but in the sense that simply knowing there’s a whole is itself a delight. You can read the Locas stories and know Maggie, not as you know a friend but as an infant knows that image in the mirror — as aspiration, as self, as miracle.

_______________________

And, of course, as illusion. The reflection in the mirror, the coherent past and present I, is a misrecognition — it’s not a true self. Jaime’s use of Maggie as nostalgic trope, then, functions as a deceptive, perpetuated childishness; a naïve acceptance of the image as the real. Consider Tom Spurgeon’s take on “The Death of Speedy”:

Hernandez’s evocation of that fragile period between school and adulthood, that extended moment where every single lustful entanglement, unwise friendship, afternoon spent drinking outside, nighttime spent cruising are acts of life-affirming rebellion, is as lovely and generous and kind as anything ever depicted in the comics form.

That could almost be a description of “American Graffitti”, another much-lauded right-of-passage cultural artifact noted for its compelling, yearning encapsulation of time. I would agree that this is a major characteristic of Jaime’s work…but whereas for Tom that’s the reason Jaime’s a favorite creator, for me it’s the reason that he isn’t. Hopey’s nightmare hippie girl schtick; the shapeless but coincidence-laden narratives; the sex, the violence, the rock and roll — it all seems at times to blur into that single repeated punk rock mantra, “That was so real, man. That was so real, man. That was….”

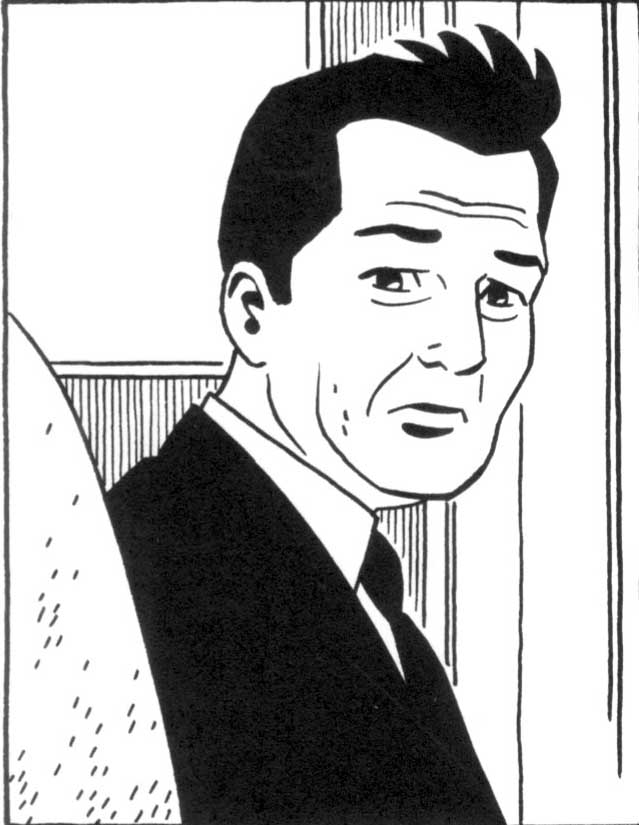

But while I don’t necessarily need to read any more of Jaime’s work ever, I do think that there are times when the nostalgia in his stories becomes not just a symptom but a theme. For example, looking again at that image of the suddenly post-pubescent Maggie from “Browntown”.

As I said, this is a moment of recognition. But whose recognition? The panel is from the perspective of Calvin, who is both Maggie’s little brother and the sexual victim of the boy Maggie is talking up. While readers see suddenly the grown-up Maggie they know and love, Calvin is seeing, perhaps for the first time, a grown-up Maggie who he does not know, and who he fears and resents as a potential sexual rival. The reader’s image of Maggie — the shock of her newfound adulthood — lets us see her, to some extent, as Calvin sees her (and, indeed, allows Jaime to subtly tell us how Calvin sees her). At the same time, looking through Calvin’s eyes inflects and darkens Maggie’s new adulthood; the overlapping perspectives capture not just the excitement of growing up, but its dangers and sadness as well. The mirror image is also a primal scene, the discovery of self also a loss of innocence. What Gallop says of Lacan might also be said of Jaime:

When Adam and Eve eat from the tree of knowledge, they anticipate mastery. But what they actually gain is a horrified recognition of their nakeness. This resembles the movement by which the infant, having assumed by anticipation a totalized, mastered body, then retroactively perceives his inadequacy (his “nakedness”). Lacan [or Jaime?] has written another version of the tragedy of Adam and Eve.

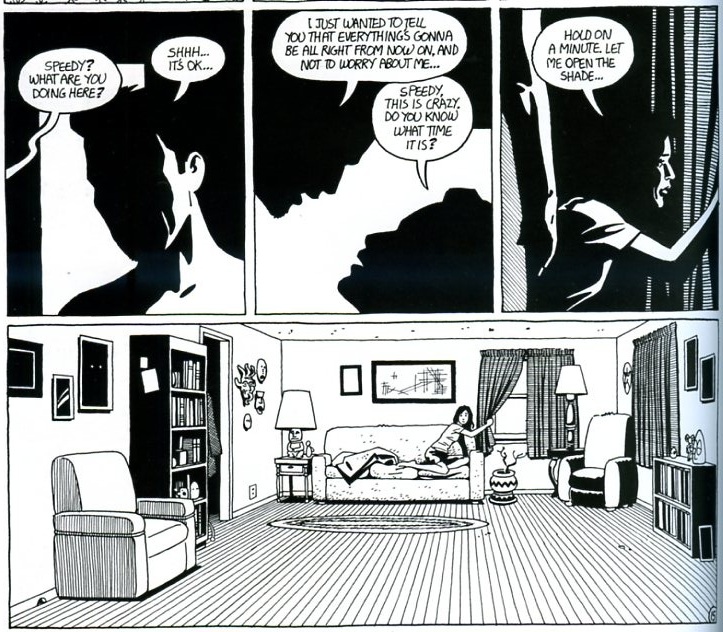

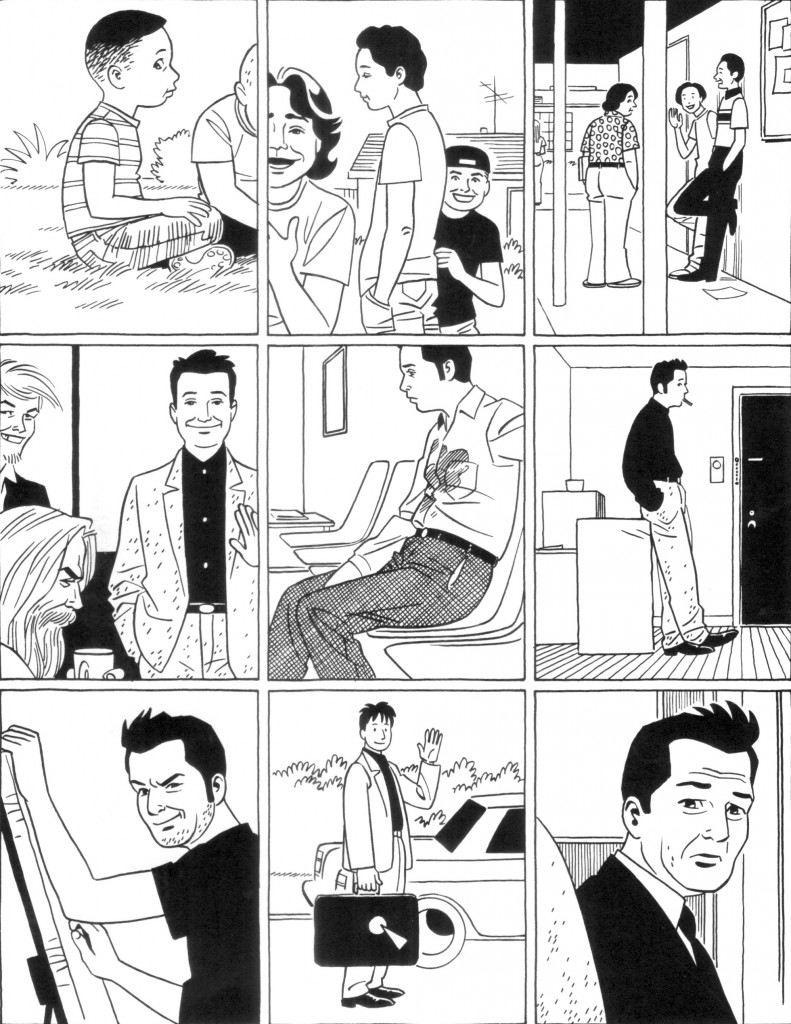

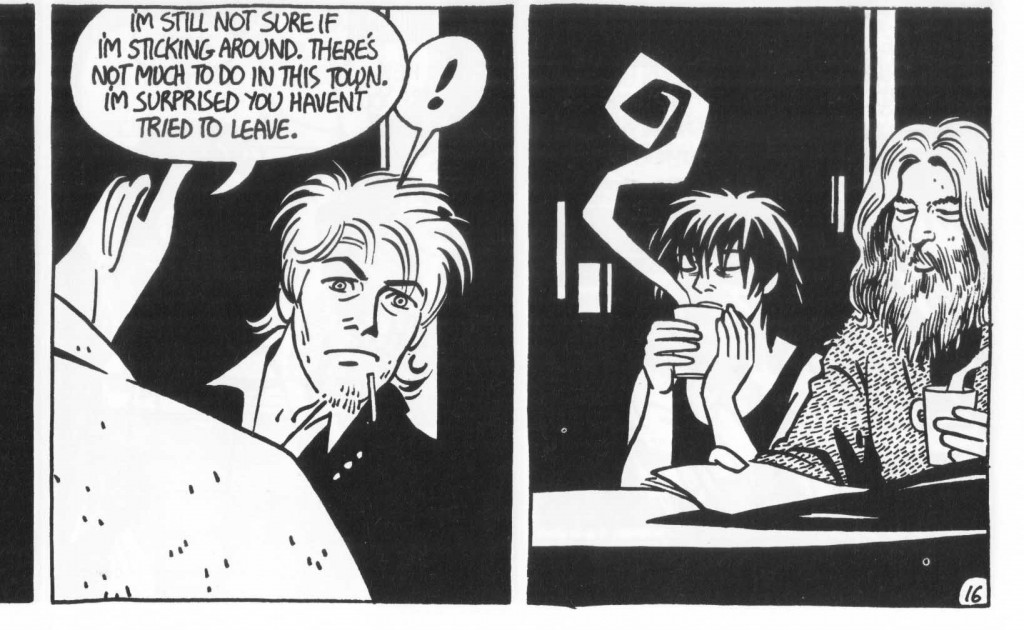

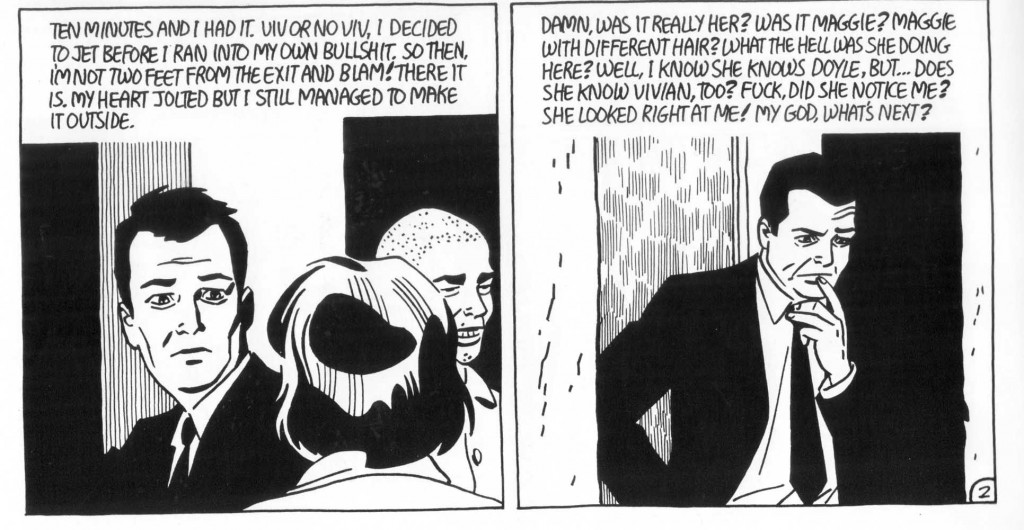

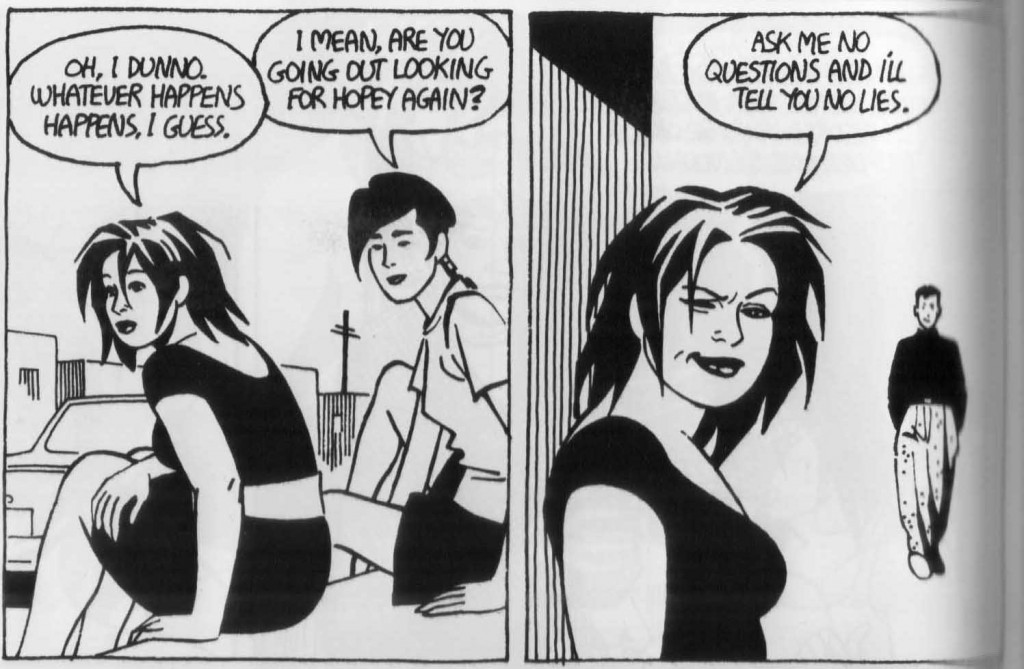

Another example of the way nostalgia is thematized is in the ghost scenes in “The Death of Speedy.”

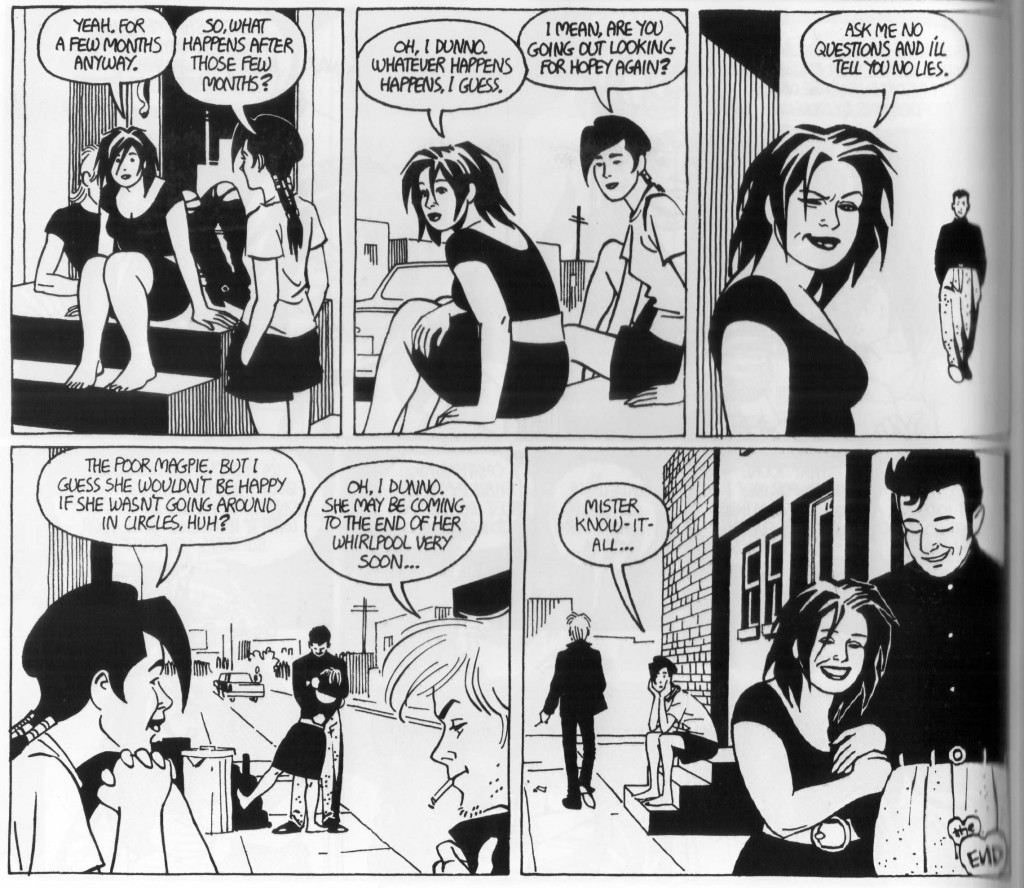

On the one hand, this, like the entirety of the derivative “West-Side Story” plot, is fairly standard issue melodrama. But in the context of Jaime’s oeuvre, there’s something (eerily?) fitting about Speedy’s disappearance into a darkened silhouette, a kind of icon of himself. Speedy’s a projection, a specter given meaning only by his past. But that’s not just true for Speedy — it’s true for everyone in the Locas stories, who appear and then disappear and then reappear further up or down the timeline. A ghost is a kind of distillation of nostalgia, a memory that walks. At moments like this in Jaime’s work, the compulsive authenticity claims become almost transparent, as everyone and everything turns into its own after-image. We cannot see the present without seeing the past and the future, which means that we don’t ever see anything but an illusion, an image of coherence.

This is perhaps one way to read the conclusion of The Love Bunglers. Many people have read it as a happy ending for Maggie and Ray; the final triumph of romance after many trials. Thus, Dan Nadel:

In the end we flash forward some unspecified amount of years: Ray survives and he and Maggie are in love and Jaime signs the last panel with a heart.

And maybe Dan’s right. But it’s also certainly the case that that ending is only reflection; it’s what we want to see in the mirror.

Two Maggies side-by-side look in two mirrors at two Maggies. We see doubles doubled, the Maggies we love seeing the Maggies we love. This is the way cartooning works; one image calls forth another and another, the characters become themselves through sequence and repetition. As Dan Nadel says, “It just works. They’re real.”

But at the same time as it solidifies Maggie, the doubling of the mirror stage also disincorporates her. The second Maggie in the mirror…doesn’t she look younger than the first? Is time passing, or is the mirror image just an image — the future Maggie that present Maggie needs to see in order to make the past Maggie cohere? If the happy-ending Maggie looking in the mirror is just a dream to retroactively solidify the grieving Maggie, perhaps the grieving Maggie looking in the mirror is herself a dream, an image to confirm the tragedy. And so it goes; Calvin’s unlikely assault is an image there to give weight and shape to his childhood trauma; Maggie kisses Viv and is rejected by her to give weight and shape to their past — or and simultaneously the past gives weight to the future, and on and on, image on image, through the never-ending jubilant shocks of misrecognition.

__________________

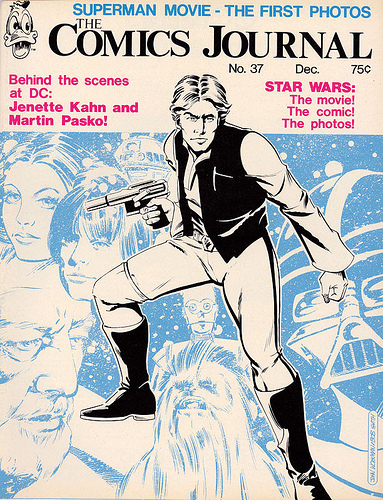

Jaime’s oeuvre, I think, can be seen as a mirrored engine; turn the crank and nostalgia is infinitely reflected. It’s an impressive delivery system. As with the Siegel/Shuster Superman, or the Twilight books, I can see the appeal, even if, for me, there’s something more than a little off-putting about the efficiency of the mechanism.

__________

The index to the Locas Roundtable is here.