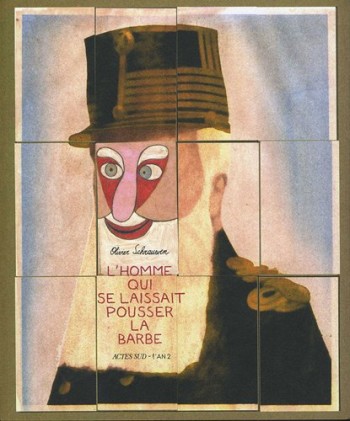

The Man Who Grew His Beard is a somewhat unexpected offering from Fantagraphics, a publisher known for its broad interests in classic American and European reprints, grungy undergrounds, “reality-based” dramas, and autobiography. The chief aspect which surprises in this anthology of stories by Olivier Schrauwen is its deeply entrenched formalism. Perhaps the closest thing to it in the Fantagraphics catologue might be Kevin Huizenga’s periodic forays into formal playfulness in Ganges, but even here the mood is much closer and more empathetic; not so much the arm’s length mental instability that can be found in Schrauwen’s narratives.

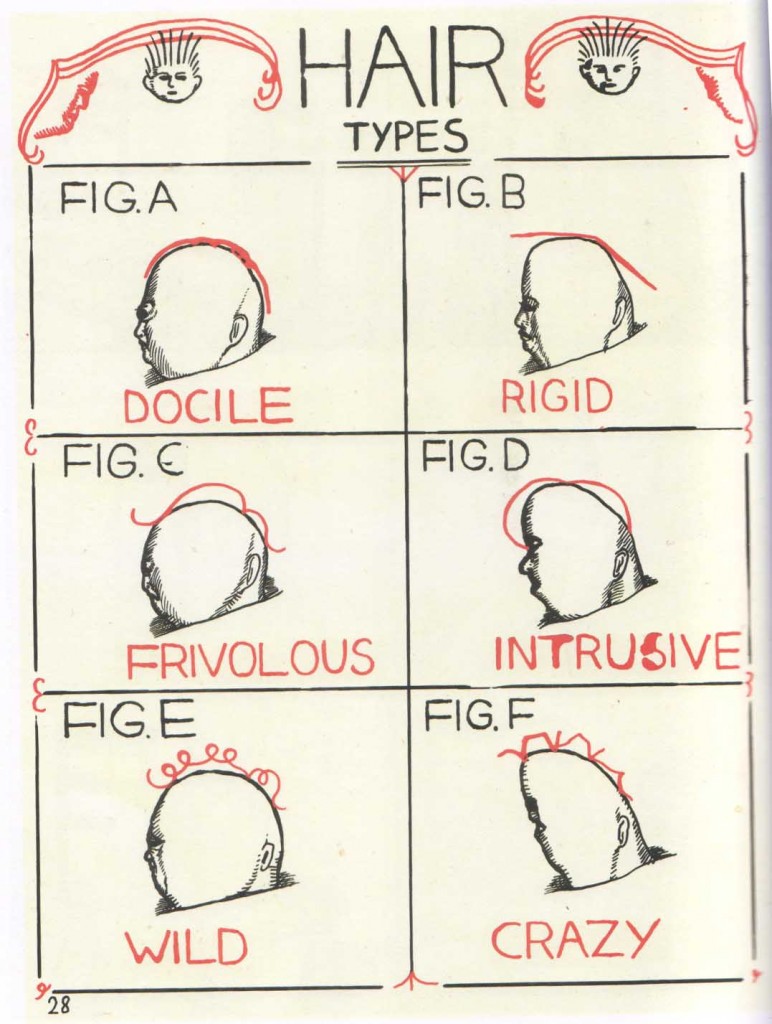

Schrauwen’s stories demand a certain degree of rereading, a flipping back and forth between pages and stories to decipher the playful code keys elaborating on the language of comics — the cartooning short hand, the persistent thematic fixtures and their variations. The story “Hair Styles”, for example, gives us a 6 fold division of grooming which is then further subdivided into a kind of follicular phrenology — a visual depiction of a kind of cartooning determinism where form dictates function.

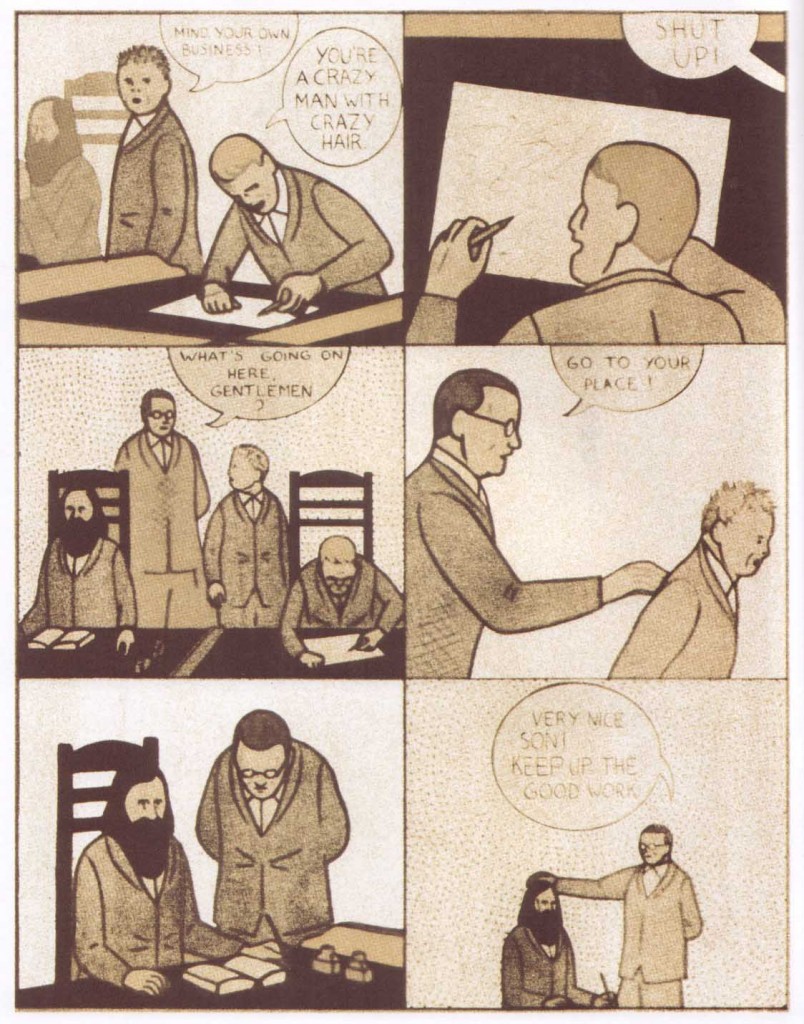

Thus, a character with “crazy hair” ultimately acts in a wild and disinhibited manner before being put in his place.

In contrast, the taxonomist among these practitioners is singled out for effusive praise by a bespectacled onlooker (one presumes an analogue for that species of writer now known as the comics critic).

The besuited illustrators are very far from the general conception of cartoonists and take on the semblance of academicians in a drawing room. The task at hand (the aforementioned taxonomy of cartooning hairstyles) and the nature of their dressing are intentionally incongruous. On the one hand, the story could be seen as mere playful nonsense. On the other, a wry comment on rigid or fanciful cartooning systems; a gentle poke in the ribs for those taken with definitions and categorizations, a reminder of the medium’s humble roots.

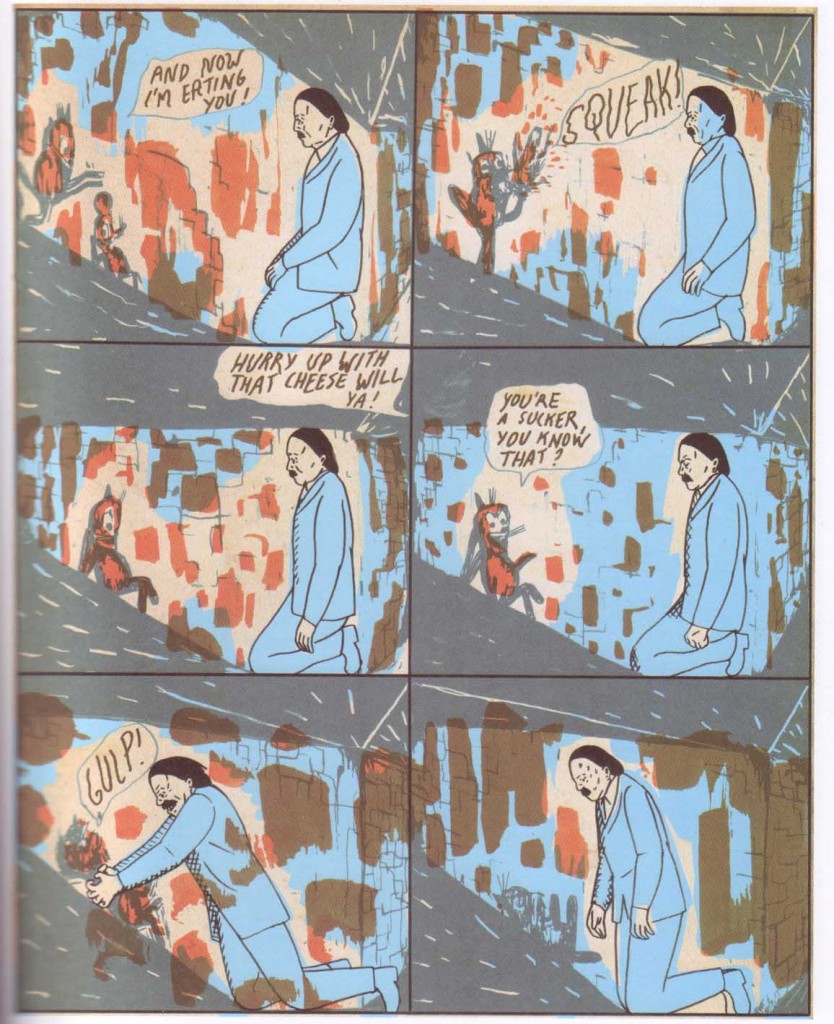

The rest of Schrauwen’s stories suggest that this is as much self-criticism as a humorous review of cartooning practices, for much of the work in this collection has a jaunty yet “high-minded” tone. This attitude is carried over to Schrauwen’s next story, “The Assignment”, where the participants are now challenged to create a story featuring a cat, a table, a bottle of milk, a mouse, a piece of cheese, and Mr. Peters.

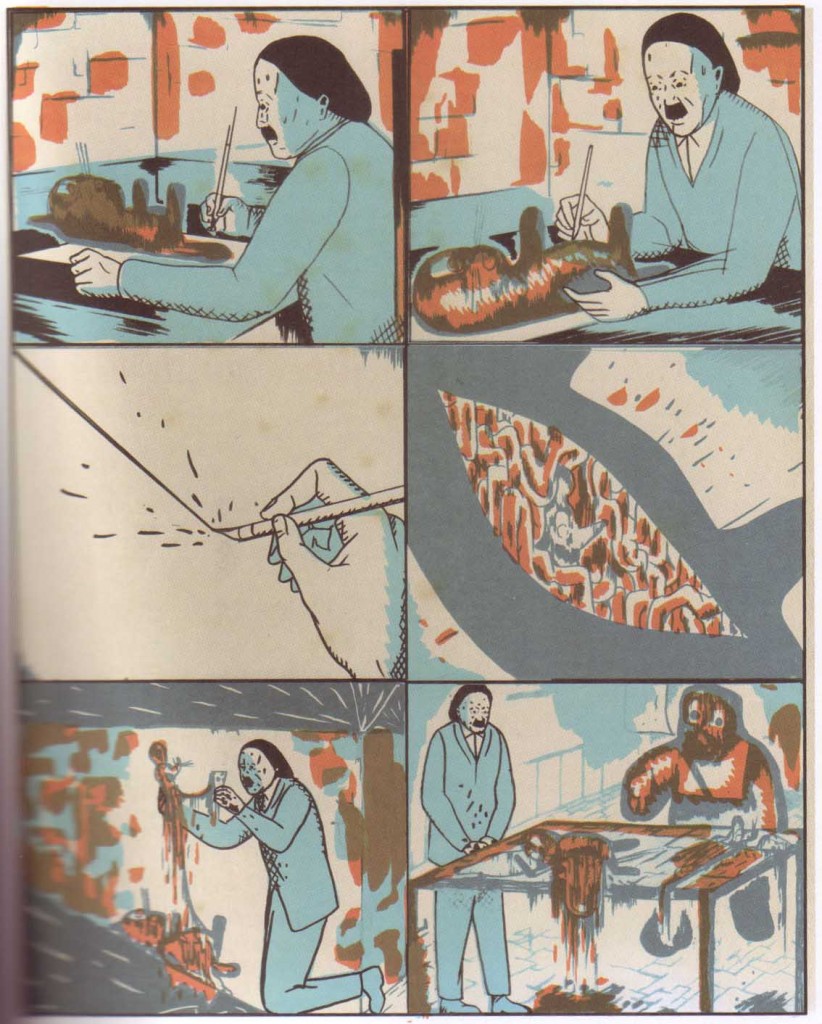

Part of this is a transposition of Mattioli’s Squeak the Mouse which is itself derived from Tom and Jerry. The final drawing of a dead cat is deemed unacceptable by the instructor-critic whereupon a graphic dissection of everything that has preceded this point is carried out — the gradual peeling back of the layers of skin and intestine of a dead cat to reveal a point of origin.

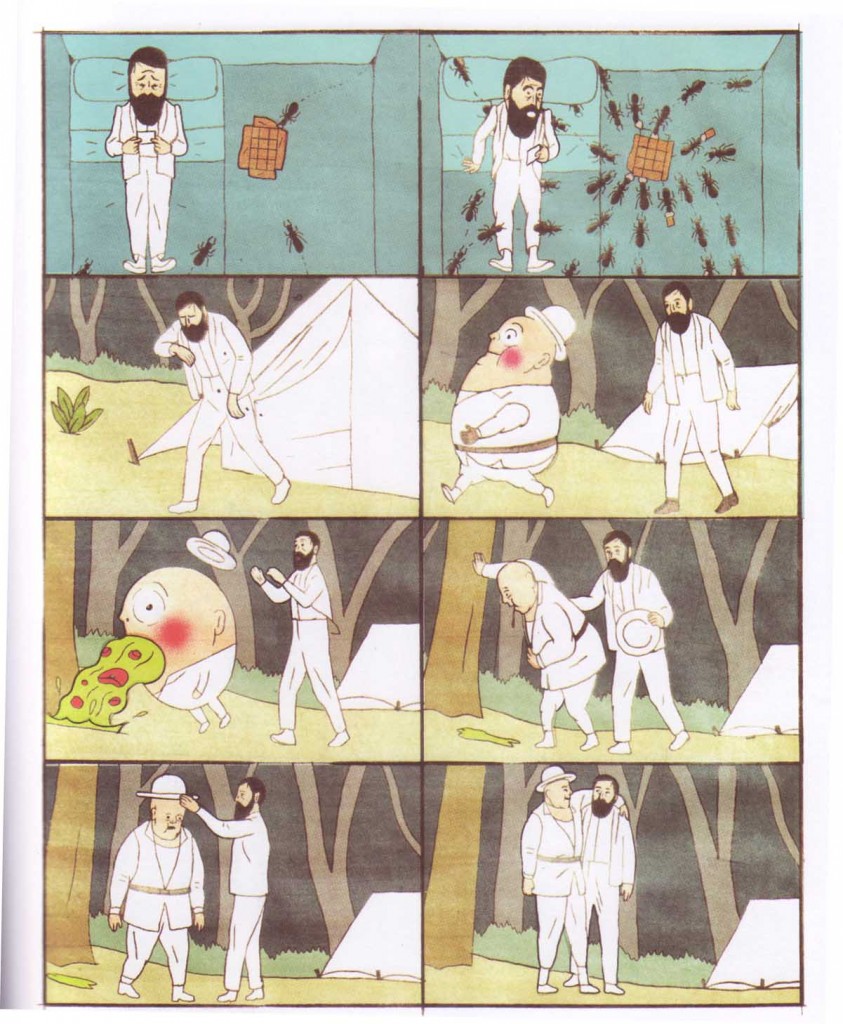

This codifying and deciphering of different realities is seen again in the story “Outside/Inside” which presents us first with the physical interactions of Schrauwen’s familiar bearded protagonist before proceeding to the multi-colored ramblings of a deranged mind to explain everything that has gone on before.

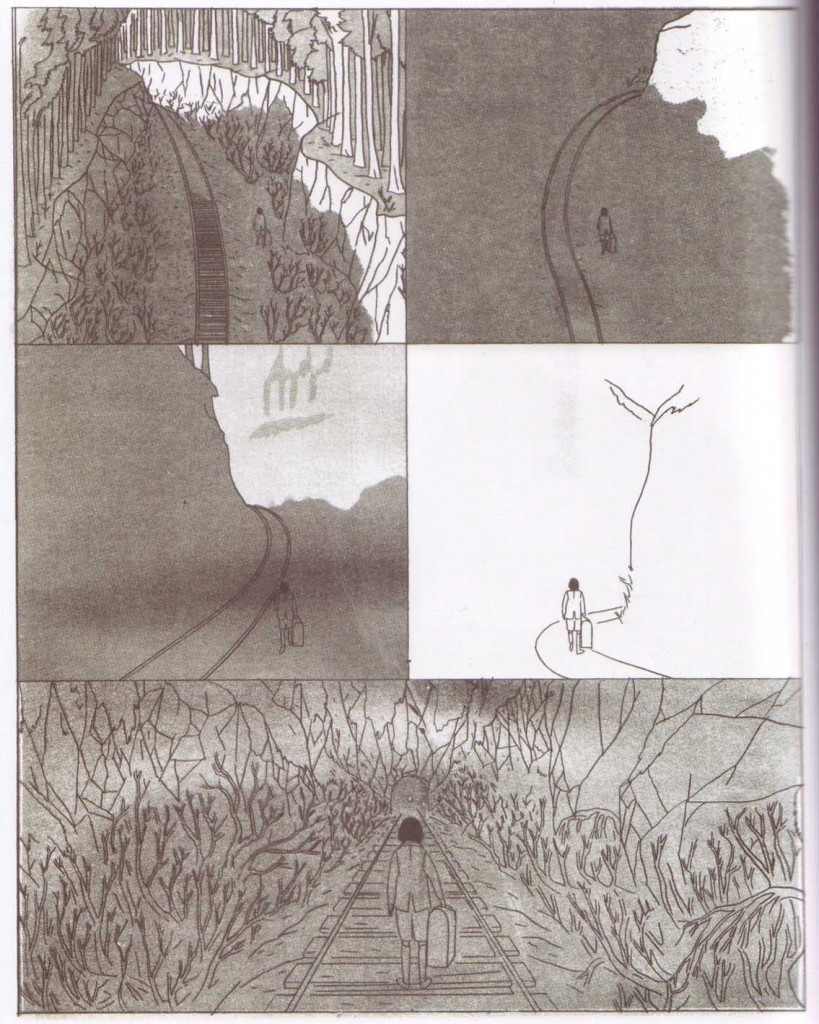

This motif is recalled in the penultimate story in this collection, “The Imaginist”, where the shadowy hues and lines capturing the broken, shriveled body of humble reality are juxtaposed with the kaleidoscope of hues which make up a stroke victim’s imaginary world. In all of these tales, there is the suggestion that there is nothing quite so shabby as reality.

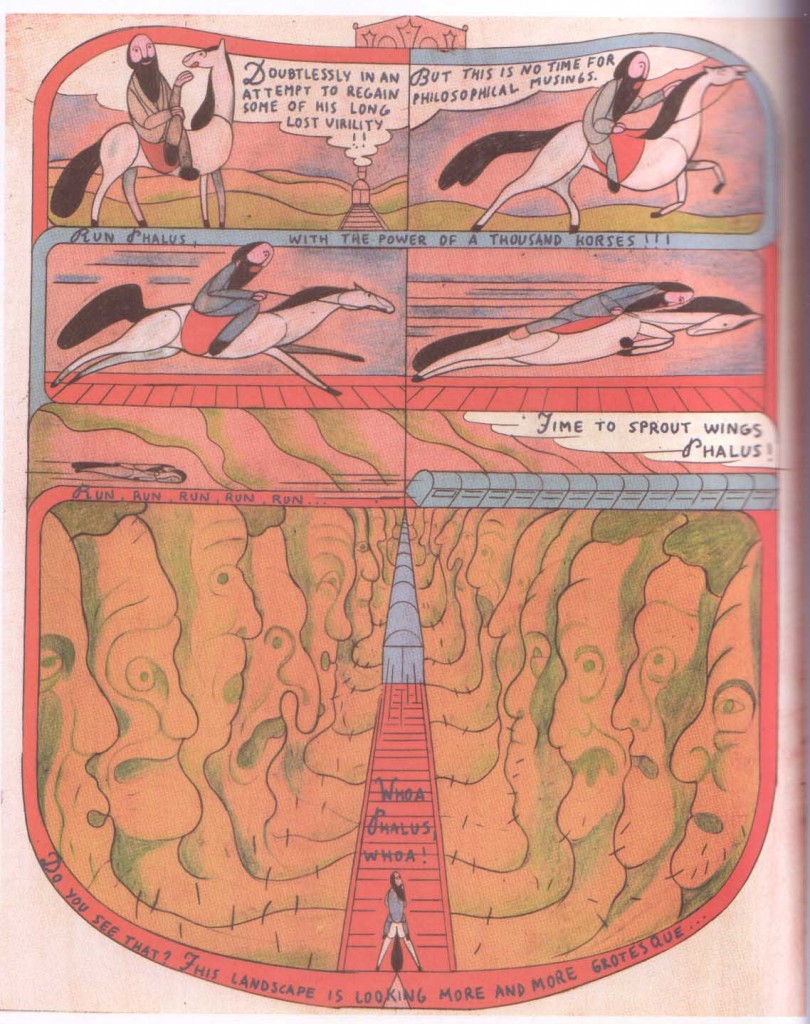

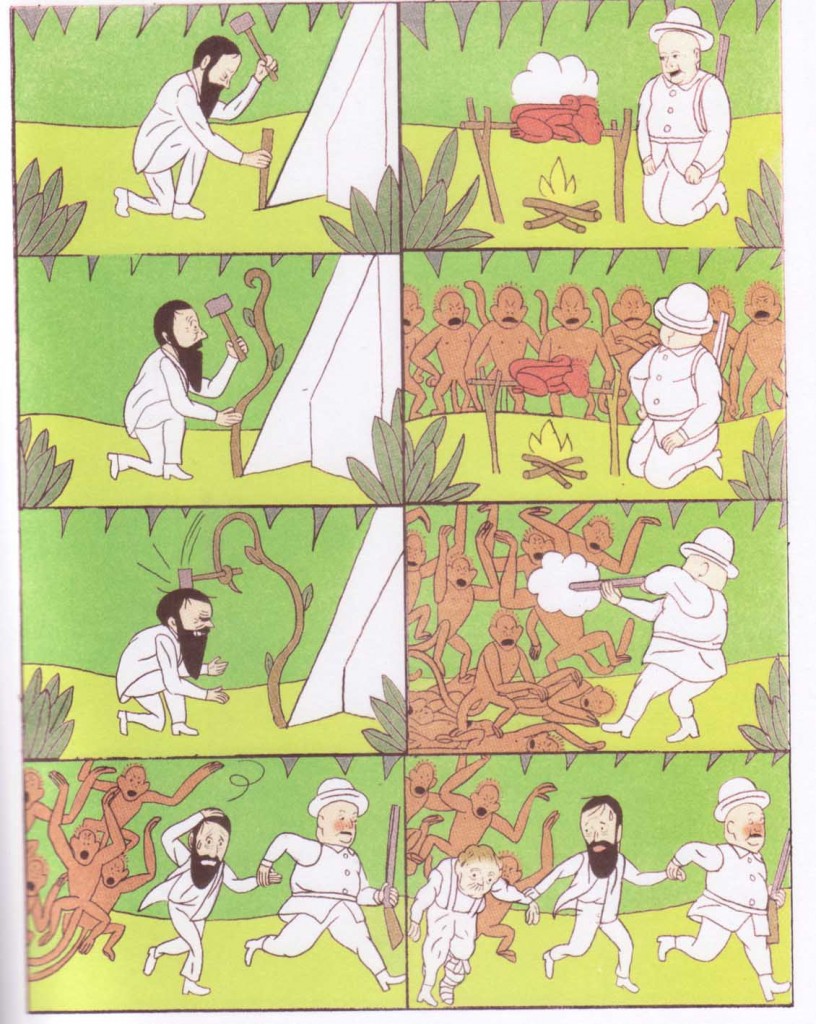

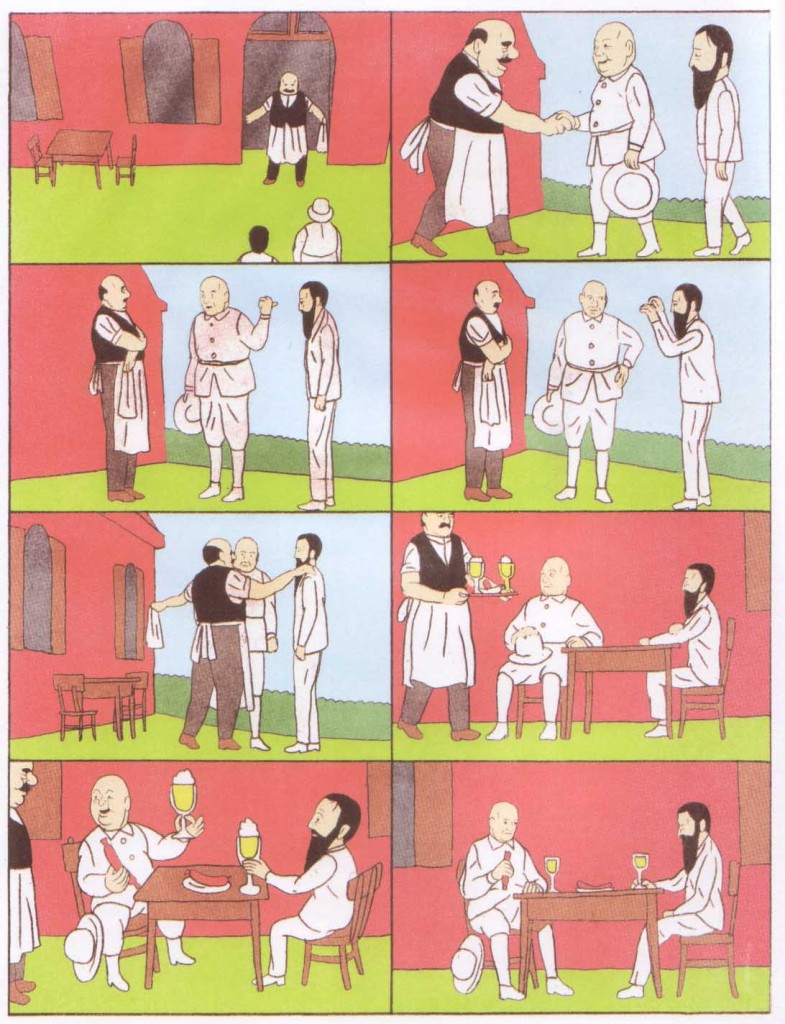

These exercises are diverting but fall short when compared to the first story in Schrauwen’s collection (the wordless “Chroma Congo”) where the barriers are flexible, mutable, and barely discernible; a world perched precariously on the edge of dreams and the fantasies of Leopold II (who appears again as a mystical talisman in “The Imaginist”).

The protagonist (that familiar bearded figure again) is sensitive yet solitary, compassionate yet complicit. His rotting mind is conjured up in an ant-ridden slab of Belgian chocolate, the over-sized bilious faces, and the stunted monstrosities which inhabit the African landscape. It will come as no surprise that Schrauwen’s work has been compared to that of Winsor McCay (the colors, the permissive attitude towards perspective and proportion) both in reviews and in his publicity material.

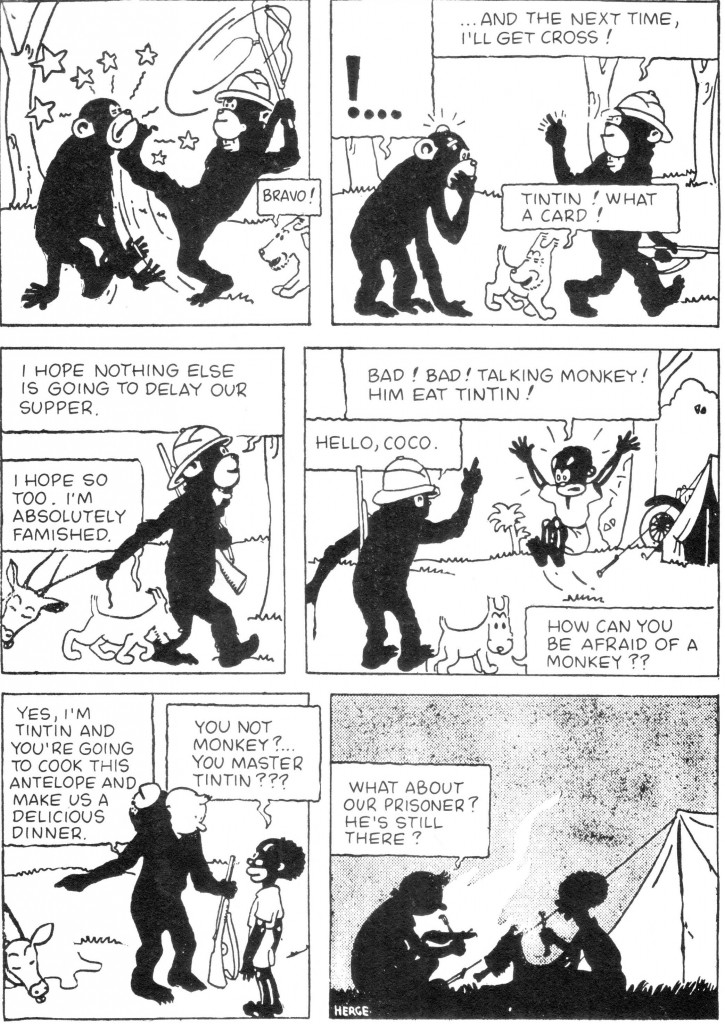

The chromatic shakiness — that disavowal of shadow in favor of bright, light pastels — recalls Herge’s Tintin, the riverboats which stream before our eyes, Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. There is not one glimpse of an actual African. This world of menacing hippos, screaming monkeys, and rifle safaris seems a silent comment on the validity of Conrad’s vision of a dark continent of swaying “scarlet bodies” wearing mangy skin[s] with pendent tail[s], shouting “periodically together strings of amazing words that resembled no sounds of human language”, “like the responses of some satanic litany”.

All of this far away from that semblance of normality (the Belgian sausages and cold beers at sundown) and civilization built on the banks of the Congo as seen in the final pages of the story.

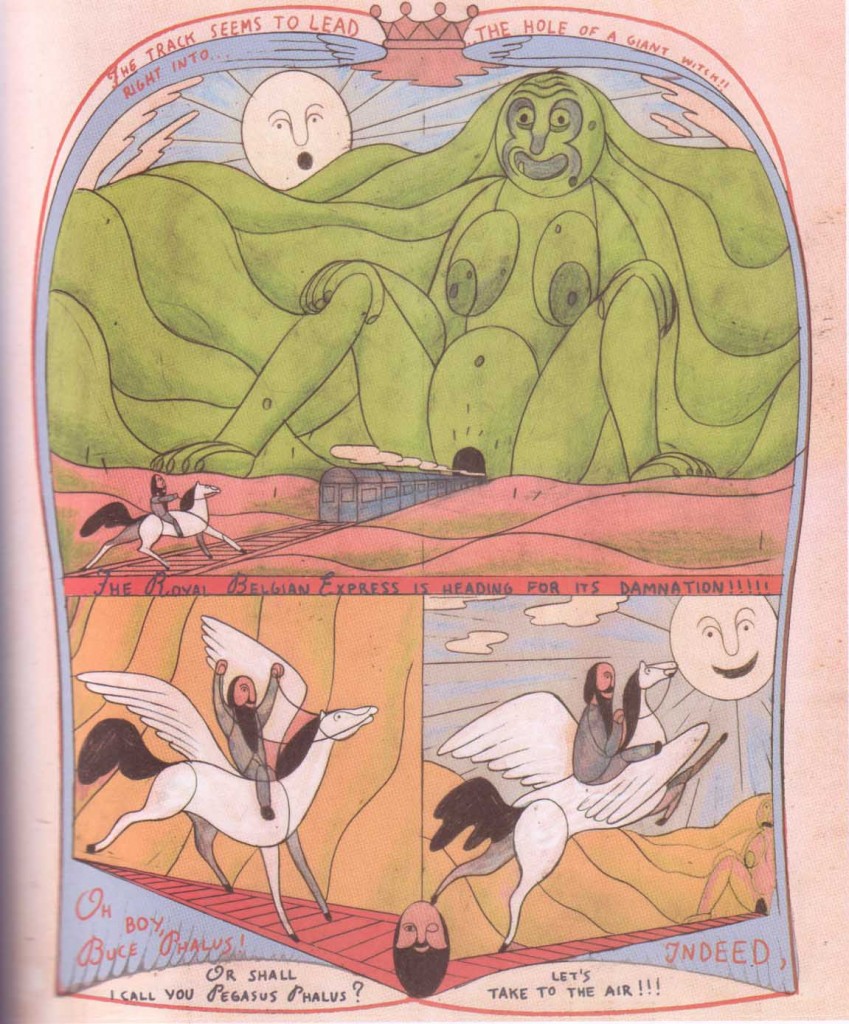

The Royal Belgian Express “heading for its damnation”, the tracks seeming “to lead right into the hole of a giant witch.”

Further Reading

A review by Bart Croonenborghs

A review by John Dermot Woods at Faster Times