Wrapping up our roundtable on Eddie Campbell’s Alec comics here at HU, we present to you an extended conversation with Mr. Campbell himself about work, life, and fate.

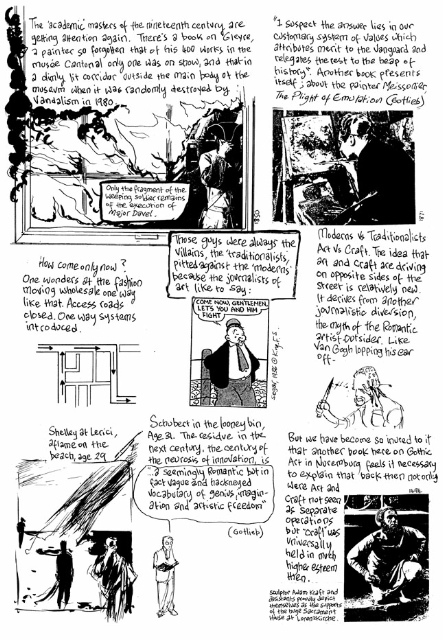

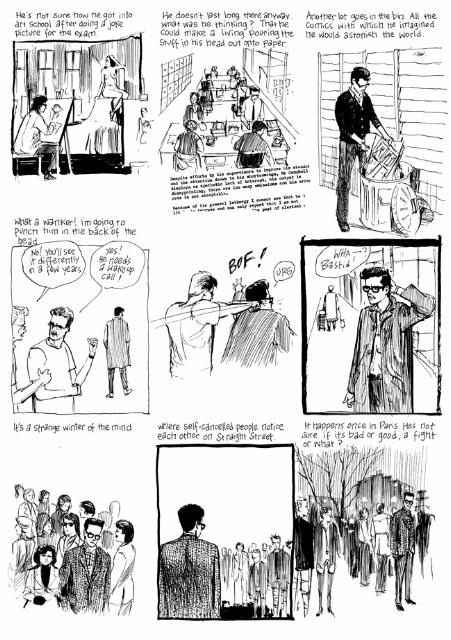

The interview was conducted via email during the course of the past two weeks or so. It focused primarily on the Alec comics as collected in The Years Have Pants (2009), so all page references, whether unspecified or in the context of individual stories, are to the pagination of that book. Except for when we talk about Campbell’s most recent personal book Fate of the Artist (2006), which is not included in Pants. I should note that Caroline Small (Caro) graciously stepped in at the eleventh hour and formulated a couple of incisive questions about that book that I couldn’t have come up with myself. They have been inserted near the end.

My thanks to Mr. Campbell for taking the time and for helping out so promptly with edits and images. ‘Nuff said!

Authenticity

At the beginning of How to Be an Artist you write with a certain amount of irony, but fundamentally seriously, “I will only lie in the service of truth.” This seems to me a good starting point for discussing your autobiographical work, since Alec clearly has had a complex and evolving approach to truth, with the issue perhaps most clearly articulated in Fate of the Artist. What is your truth in autobiography?

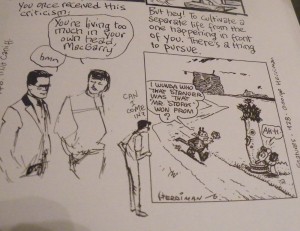

Firstly, let’s dispense with ‘autobiography.’ I felt uncomfortable when that word crept into comics, and even more so with the more recent ‘memoir,’ which I believe arrived with [Alison Bechdel’s] Fun Home. In the contract of fiction a storyteller says ‘let’s make believe’ to his audience. Let’s make believe there’s a person named Alec MacGarry. If the outline of this character’s life largely resembles my own, that’s interesting, but it doesn’t mean we’re no longer ‘making believe.’ And just to remind you where we are, let’s make believe he makes a bargain with the deity Fate, who allows him three wishes. The “I will only lie in the service of truth” is just a variant on “Every word I tell you will be true. It happened long ago…” It’s just opening the door. It’s part of the storyteller’s craft. I’m looking at two books on my shelf. One is The Life of Thomas More by Peter Ackroyd, and the other is The Collected Stories of O. Henry. I’d put my book beside the O. Henry.

I understand, but you’re still working in a reality-based register with your Alec comics, no? And at least in the case of How to Be an Artist there must have been documentary concerns, since it concerns in part an extended number of public figures in the comics world. I guess that what I’m interested in is your way of negotiating material that is in large part lived with your wish to craft a story, and the reason I’m asking is because reality-based material has been so central to the development of comics in the past few decades – a notion of, or at least a feeling for, truth must be essential to it, as you indicate.

Okay. First thing that springs to mind here is The Salon by Nick Bertozzi, and I can’t recall where I read this, in an interview somewhere, but while he was interested in Picasso and Braque and the story of Cubism, he felt that more was needed for a ‘graphic novel,’ and so he introduced this magic absinthe idea, or whatever it was, but it was a supernatural element. I was so disappointed; I mean not in the work itself, but in that there was a presumption that comics can’t function without a super-element. As though you couldn’t find enough daftness for cartooning purposes in among Picasso, Gertrude Stein, and that whole nutty circle without needing to bring in supernatural stuff.

In my own case I was dealing with a much smaller event, the ‘graphic novel’s’ first crash and burn in the early 1990s, and there certainly wasn’t any need to make things up to keep it interesting. Just figuring it all out was enough of a feast. A good storyteller can make a banquet out of much less than what was on offer in that case. But I think comics are mostly dealing with a very immature taste among its readers. There was a fellow pitching an idea at San Diego, and I can’t remember why he was pitching it to me, perhaps I was listening just to be polite, but he started ‘There are these vampires—‘. I cut him off. ‘Stop! I’m bored already.’ There’s only one vampire I have time for and that’s the Count on Sesame Street.

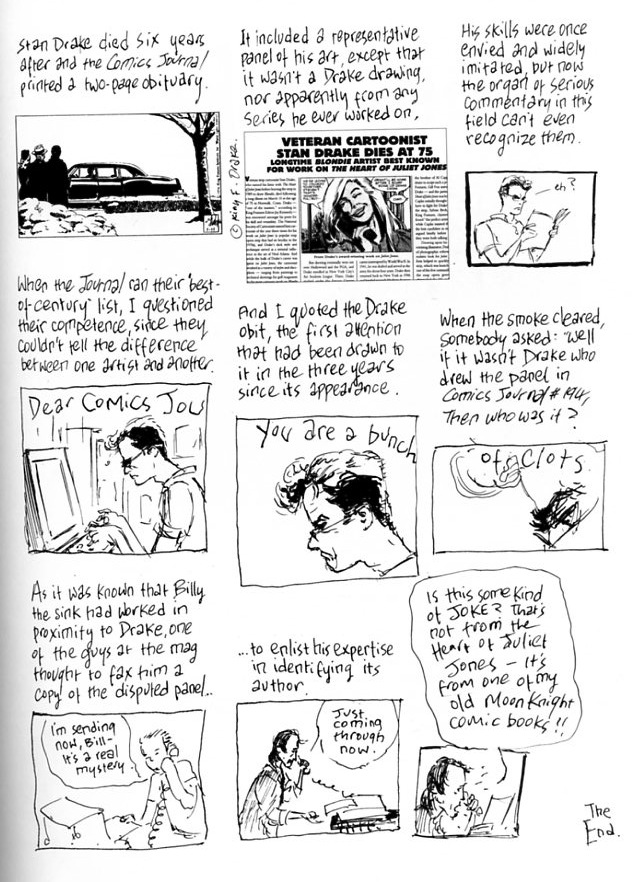

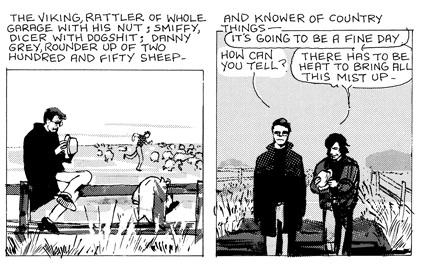

How to Be an Artist could have been done as a complete fiction quite literally, except it would have taken five times as long to do. Referring to real artists living and dead really wasn’t what it was supposed to be about. That was just an extra sheen. Fictitiously I wanted to create a sense of a lot of names and styles, and some of these would appear once and never be heard of again, some would recur, and others would become significant players in the drama, while others yet again would be established as a category of ‘old masters’ that could be referred to almost in the prayers of the protagonist (King, Herriman, Caniff). In fact there is a sense that Drake, in my epilogue, is the last of these old masters to pass away (even though he isn’t literally – Feiffer is still alive – but my point is that the reader should think of it as fiction).

Also, I was thinking about Tolkien and the way there are names that exist in the mythology of Middle-Earth, and also the way some of these characters are about to enter into that realm, like Galadriel, if I’m remembering it correctly, it’s been a long time (I adored the Silmarillion). Like Tolkien, I wanted to establish a dense mythology, but in a very short space. And on top of that, the effect I wanted, is that this is what the artistic environment is made up of. In fact it’s what life is like. School, work, etc. At first there is a crowd, and in time individuals stand out, and there are departed individuals that are only ever referred to and are never met, and in time you may become a significant figure yourself as you achieve credit for your actions. The novice has to negotiate his way down a populated road.

I could have made up a lot of stuff, names and titles of their works, like Eisner did in The Dreamer, but why cheat the reader of an extra layer to the work? And you could do the same thing for a musical environment, or art of any sort. So rather than ‘drop names’ as one critic has said, it was necessary to represent each occurrence of such a personage in my story by showing an image from his work. And then, so that this didn’t seem like an arbitrary art-book thing, I challenged myself to find an image that commented on what was actually happening at the exact point in the story into which it was being inserted. It works as often as not. So anybody just skipping those panels because they’re not interested in that artist, is missing the meaning of the scheme. An average reader, I have discovered, is only willing to recognize a limited number of characters, six or seven or whatever, and I’m sure somebody somewhere has tabulated it. Beyond that they tend to complain.

So just pretend they’re made up. Although, as it happens, a lot of those old masters are in print now, who weren’t when I drew my book, so maybe a lot of that stuff is less obscure than it might have been. And Umberto Eco in his Queen Loana used a lot more obscure stuff than I ever did…. There was a moment when my confidence in what I was up to threatened to fail, but I came across a couple of quotes that shored up my resolve. The first was “Literary history is a modern invention and so is the automatic sense which a modern writer must have of his location in the flow of literary time.” The full thing is on page 249 of my book. It encouraged me to believe I was on the right track. The other one relates to Alan Moore’s position in the story. When I knew I was going to end with the Big Numbers fiasco, and I knew from the start, I started working in allusions to chaos theory, and then I stumbled upon that great paragraph from R.G. Collingwood “The same instability which affects the life of the individual artist reappears in the history of art taken as a whole…” He glimpsed the fractal idea way back in 1924. I had to put the whole quote in there.

Anyway, there was an investigative angle to How to Be an Artist. Why do these things fail? Art in the bigger sense, and the artist’s life as a microcosm of that. And since it was my intention to find useful answers to these questions, there was no room for making things up. Even if I’d changed a name it would have ruptured the fragile fabric of it. Apart from MacGarry of course, but by that time everybody accepts that as a metaphor for ‘Okay, make yourself comfortable and I’ll tell you a story.’

I watched The King’s Speech last night. Good movie, and it’s amazing that a story about a guy overcoming his stammer gets to be Picture of the Year, but a few things niggled as being implausible, and when I looked into it, sure enough, those were the parts of the story that were tweaked ‘for dramatic effect.’ In movie-making there’s a presumption, in fact it appears to be a commandment, that ‘there can be no drama without conflict,’ and so conflict has to be manufactured where it can’t be found growing naturally. I’m referring in this case to the depiction of King Edward, who has to be made somewhat unlikable for the purpose of making George look good. In another story it’s easy to make Edward’s story the love story of the century. He gave up his throne for the love of a woman. But here he’s an air-headed Champagne Charlie who mocks his brother’s speech impediment. That’s the movies for you. As soon as I see the cheap mechanisms at work, it tends to weaken my willingness to suspend disbelief. (Lest you assume I’m against movies per se, there are some that I do have an enduring fondness for: prime Laurel and Hardy, such as Blockheads from 1938, Howard Hawks’ To Have and Have Not, Jules Dassin’s Rififi, and many more, none of which are based on real events.)

Before we leave the notion of autobiography behind, I wanted to ask about your distinction between that term and what you are doing – isn’t all autobiography, even as commonly understood, a kind of storytelling? Does the term seem to constrictive for what you’re trying to do?

After I sent you my previous I thought to myself, what was I trying to say there? My point I think, if I were to finish circling around it, would be that I resent mechanical interference in narrative configurations that occur naturally. What attracted me to real life events in the first place was that they always happened in ways that didn’t fit my preconceived notions of narrative logic, arrived at by years of reading books and comics and watching movies. When I first started thinking about this I’d take bits of business that I’d observed in real life and then fit them into my work. But later I’d resent the damage I had to do to the observed moment to make it fit in. There are non-obtrusive things you can do, like juxtaposition, or a bit of careful pruning can help nature along. And a short story doesn’t need to arrive at a snappy conclusion. Even as recently as the new stuff in the The Years Have Pants there are a couple of places where my interfering hand may have gone too far. Hatfield and Fischer’s ‘tiny fragments’ theory is a useful reference here. Sometimes the preciousness of the found moment is best preserved by keeping it along with other found moments and not trying too hard to connect them.

Regarding autobiography, yes it is a kind of storytelling. It’s just that I consider it the shelf of people who have done important things in the world. And ‘memoir’ by definition means looking back, which is not always what I’m doing. And a diarist is recording the days in order one after another as they happen. All of these are literary terms. Something bugs me about this, and what I’m trying to say will probably occur to me after you send your next question.

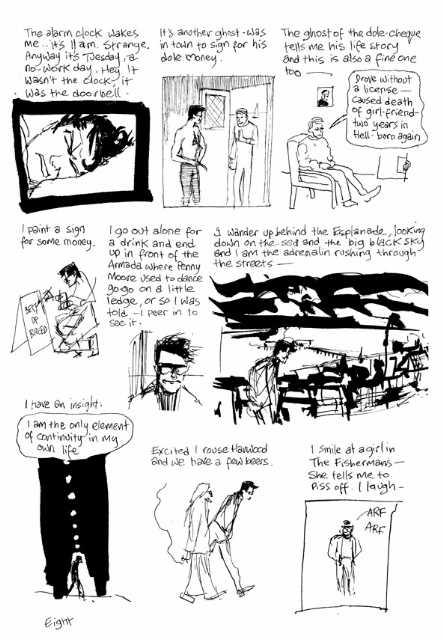

Right, I definitely see what you’re saying about found moments. In Graffiti Kitchen, however, you have this line “I am the only element of continuity in my own life”, which you end up subverting as an egotistical conceit, but which still remains what seems a certain statement of purpose. Making sense of one’s life, one seeks continuities, and reading the Alec comics in their entirety, this seems a driving principle. Would you agree?

I have to keep on answering for the egotistical blather of that young whippersnapper, Eddie Campbell. That’s my problem right there. I realize now that at the beginning of our exchange I was attempting to express my current aesthetic position, which is inevitably going to make me contradict myself, if the younger me still has a voice. If that amounts to continuity then so be it.

Thinking about my impasse in my previous response, I’m remembering that I have always been striving to get back to a more immediate kind of story-telling. I mean telling of an oral sort. Talking. In talking, one simply begins ‘I heard,’ or ‘do you know who I bumped into’, or ‘I was reading about this woman…’ (naturally establishing ‘I’ as the author and motivator of the anecdote.) However, the writing of fiction, and autobiography for that matter, involves this whole other formal way of going about things, such as: “From a little after two o’clock until almost sundown of the long still hot weary dead September afternoon they sat in what Miss Coldfield still called the office because her father had called it that – a dim hot airless room with the blinds all closed and fastened for forty three summers because when she was a girl someone had believed that the light and moving air carried heat and that dark was always cooler, and which (as the sun shone fuller and fuller on that side of the house) became latticed with yellow slashes full of dust motes which Quentin thought of as being flecks of the dead old dried paint itself blown inward from the scaling blinds as wind might have blown them.”

I can see how in that first book, The King Canute Crowd, I was trying to do that very thing with “Danny Grey never really forgave himself for leaving Alec MacGarry asleep at the turnpike”; all this creating characters and putting them in a very particular time and place. I think I’ve been wrestling with trying to defeat this aura of the literary ever since. I feel that it’s a formal screen erected between speaker and listener. On this subject, I greatly enjoyed [Michael] Chabon’s recent Maps and Legends. It’s a collection of essays I suppose, or at least that’s how it would have to be described, but it’s really all of a piece, and it involves talking about stories and telling stories. And in it I feel that he was talking directly to me without that formal thing between us, that contract of ‘Let’s make believe…’, that same situation which is where I placed myself at the beginning of this chat, which started two days ago but is probably only eight inches above here. And since the tension between one mode and the other is exacerbating my paragraphs here, maybe it’s the same tension that gives a certain frisson to my better comics, that setting up of a literary pretension and then its casual deflation.

Literature and art

In your discussions of the graphic novel you’ve raised the term ‘literary’ as a defining aspect. I take it you mean literary as a register, rather than specifically text-oriented. How are comics literature?

If you go back to where you found that reference, you’ll probably find that I was representing Will Eisner’s original intention. When Eisner used the word ‘novel’ he was alluding to literariness rather than to a ‘prose work of more than 70,000 words’ (as science fiction societies that give out awards like to define a novel). And by literariness he meant seriousness of meaning, and a book that stays on a bookshelf as opposed to a periodical that gets thrown out after its use-by date. (Curiously, a book-writer I recently encountered was nonplussed upon observing that comics now stay on the shelf forever, no matter how awful they are whereas regular books have their moment in the daylight, get remaindered and are never seen again outside of garage-sales.)

On the other hand, when I used ‘literary’ above I meant it in the sense of written as opposed to spoken (and spoken here meaning straight from brain to tongue, not reading aloud a prepared speech as in the movie mentioned above). The three-panel gag comic can still be very close to the spontaneous, to the told joke, or to the scurrilous caricature sketched on the outhouse wall. A short comic book can still be analogous to, or a rendition of, a memorized tale. But to spin a comic out for a hundred pages (or even 48 pages, as in Graffiti Kitchen, or all of the stories in [Eisner’s] A Contract With God) and do it successfully (by which I mean it holds the attention of a ‘reader’), involves a kind of long-range planning that can only be arrived at by ‘writing.’ (In the same way, the symphony could only have been conceived in an era of written music, and at some point in its evolution, The Iliad shifted from an oral tradition to a written one (As M. L. West demonstrates in his magisterial The Making of the Iliad, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011; ”…at some point Homer wrote down or dictated his material, and in the course of years or decades he composed the vast panorama of The Iliad, expanding his early draft…”)

I could draw a large number of images, as say for instance Picasso does obsessively in his ‘Artist and Model’ series of Dec ‘53/ Jan ‘54, in an improvised, purely mind-to-hand way, or as Al Columbia did equally obsessively in his recent Pim and Francie, but something like The Arrival by Shaun Tan, even though it has no words in it, is a book complicated enough (this is not a qualitative argument) that at some point in its evolution, it would have required a written plan, even if the writing consisted entirely of hieroglyphs that neither you nor I could interpret.

In this way, comics become a kind of literature if we do not intend that to mean that they now reside on Parnassus, as a fellow comics practitioner seemed to be presuming was my intention on a panel, a few years ago, for which I had pre-proposed the subject “Will the literature of the future have pictures?” ‘Comics are not literature, they are comics!’, he declared emphatically at the outset, leaving us wondering where the discussion could go next. (This was not at a comics event, but at a writer’s festival, which was casting a sidelight on the ‘graphic novel’ phenomenon, and so the literary angle opened a potential channel of connection.)

And would you say that comics as literature in this sense is constituent of your conception of the graphic novel? Clearly it is not the only criterion, and I know you’ve more or less disavowed the term because of its dissolution in the market, but is it salvageable, and what role would this literary aspect play for it?

An artist usually wants to be part of something bigger than himself, but ‘the graphic novel’ no longer seems like any kind of worthwhile aspiration to me. Nor does the prose novel for that matter. My thinking has been floating adrift for some time. I’m working hard on a new book, but I don’t think of it as being part of any current dialogue. Maybe I’ll come out of that and see everything in a different way.

In your foreword to the collected edition you write that part 1 of The King Canute Crowd was where you found your artistic voice, and that’s precisely the story that starts with that line “Danny Grey never really forgave himself for leaving Alec MacGarry asleep at the turnpike.” It’s a very ‘literary’ opening as you say (and a very fine one, if you ask me), but in some ways it feels more poetically wrought than your graphics – the generally large grid, the preference for medium- and long shots, and the general lack of dynamic panel layouts; the sketchy, notational drawing style, etc. The continuity between that through your current work makes a lot of sense to me, but I’m curious as to how you’ve refined this ‘voice.’

It takes a long time and a great effort to cut away all the dead wood and get things as straightforward and simple as you describe. The first thing that had to go was everything that was cinematic. Next, anything that looked like comic books, and most comic book readers are not even aware of the peculiar pictorial syntax of comic books, the way characters stand in a panel in relation to each other and in relation to the frame and the way word balloons sit in a panel unrelated to everything else in there. ‘Panel layouts’ is a term I haven’t used in a long time. It’s a comic book term, like ‘nine panel grid’; ‘medium shot’ and ‘long shot’ are cinematic terms. I threw all of this stuff out of my vocabulary long ago. They’re part of the dead wood. In an early attempt to start the book, the characters had the slightly enlarged heads of a cartoony style. That had to go too. To have repeated it in panel 2 would have been the makings of a ‘style.’

I read an art instructional book once, I can’t remember who wrote it, but I extracted a valuable lesson from it. That is, that an artist should spend his artistic career expunging from the work everything that he recognizes as a habit. If he finds a neat way of doing something, instead of using the trick again, he must refrain from ever doing so. He must cast it out. A particular brushstroke or a figural gesture, or whatever. Comic books are entirely made up of this sort of thing. I have a pal who loved the way Berni Wrightson drew the strings of saliva stretched between upper and lower teeth, so he borrowed the device and still uses it forty years later. Wrightson himself got it from Graham Ingels, and he may have invented it or got it from somebody else, perhaps the face of a witch in the illustration in an old book of fairy tales from the turn of the nineteenth century. So this ugly device has been perpetuated through several generations, perhaps a whole century. Acquiring an artistic voice should be a subtractive process. Get rid of everything that you recognize as a device, or an aspect of style. Try to have no style, to go beyond the idea of a style. And what’s left will be your own voice, which you can never properly recognize, and then get rid of that too. Transform yourself. The book didn’t go that far. I’m extrapolating now.

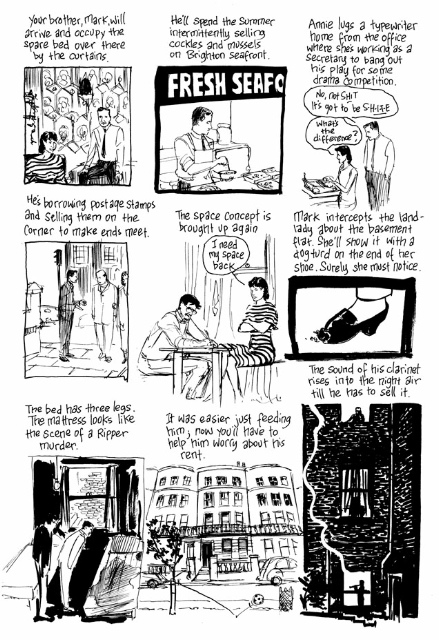

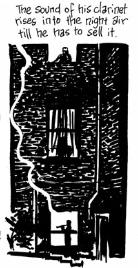

It seems to me, however, that there is still a stylistic choice involved – the stories are very determined by the narration, sustaining the notational aspect of the drawing and leaving less room for images of a more independently evocative nature. Such drawings as the silent one in chapter seven of How to Be an Artist (p. 258 in Pants) where your brother plays clarinet from the basement window of your building are few and far between. I assume there’s a conscious choice involved here, perhaps having to do with reflexive tenor of the narration?

I had to go back and check that because I remember I was consciously avoiding silent panels by that time. In going for a verticality, I’ve pushed the caption dangerously high up there so that in a quick reappraisal you’ve overlooked it.

Argh! How did I manage simultaneously to read and overlook that caption?

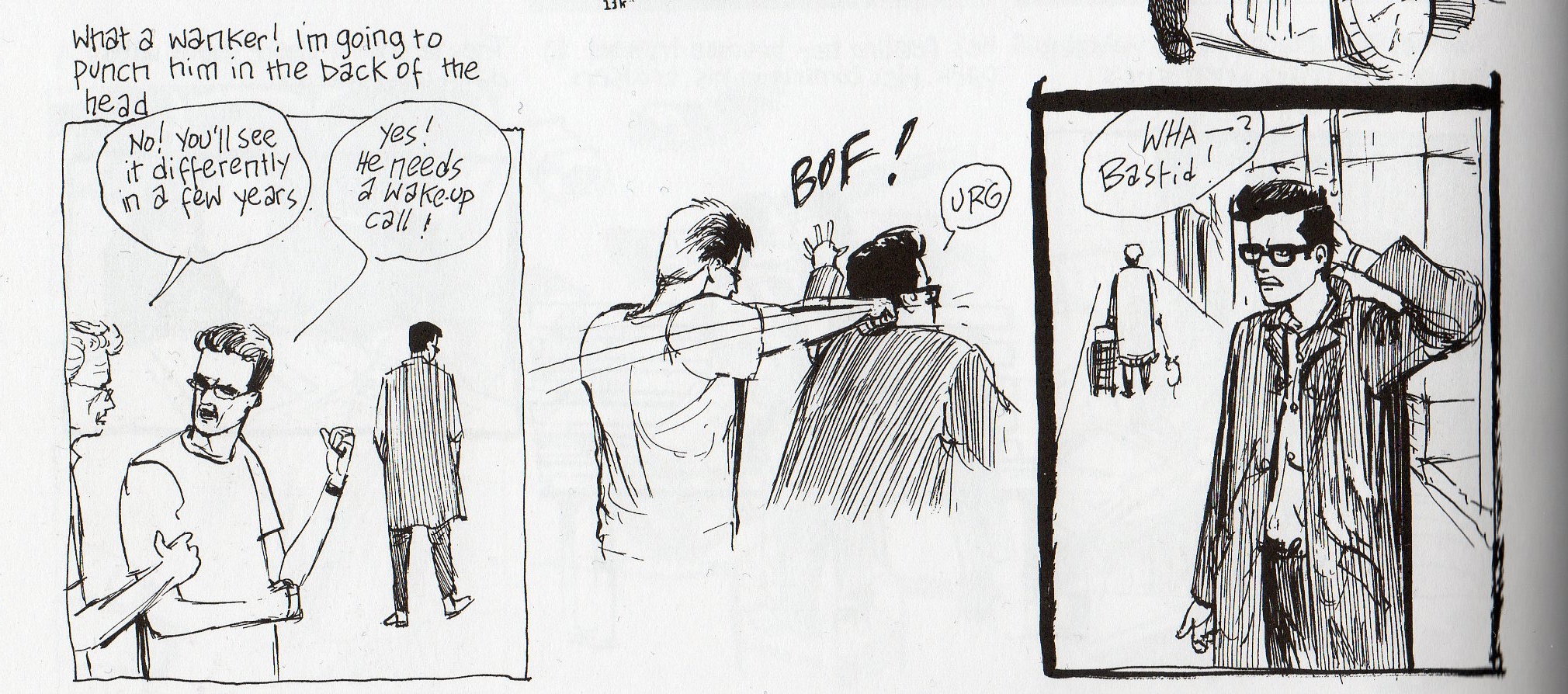

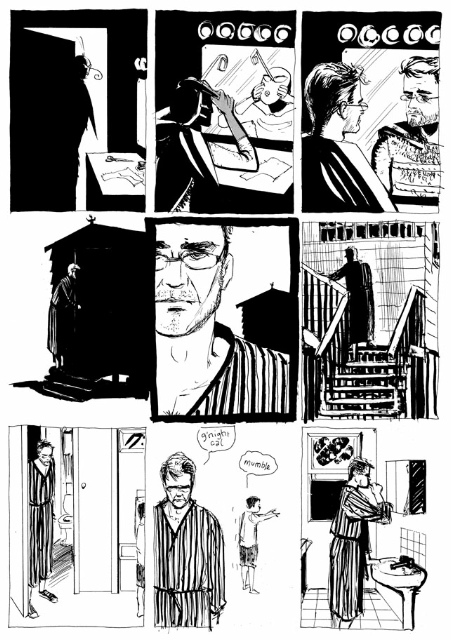

…In fact I’ve broken one of my own rules about caption placement and suddenly feel embarrassed. I shall seize upon one aspect of your question and surge ahead. Looking at it now, I feel that I was resorting to a cheap cliché there. I had decided by then that silent panels were a gimmick that belong in the Eisner-Steranko school of comics art, in which analogous techniques are found for representing time and sound (or its sudden absence). You can certainly find passages like that in the King Canute Crowd, such as page 93:

…or in close proximity, page 101. But at the time I drew those pages I would have been incapable of something as complicated as the Big Numbers fiasco (pages 305-310, or “OUCH!” on pages 468-471:

…or speaking of the wispily poetic, the graveyard sojourn on pages 569-570. For everything gained, some other thing must be abandoned).

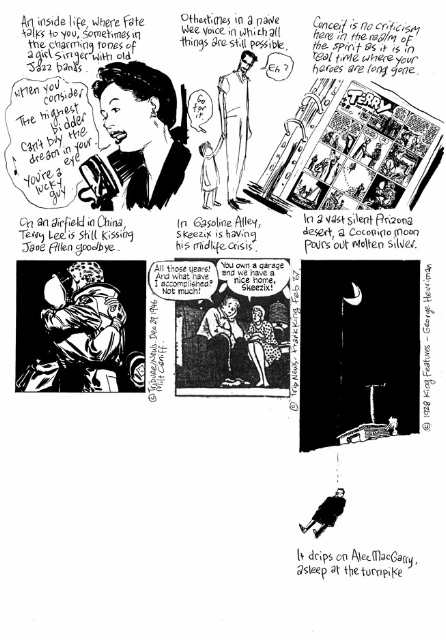

I always felt that my challenge was to make my little paper characters live in the reader’s mind. Too handsome images can be a distraction. When I read Gasoline Alley, I always prefer the workaday dailies. The Sundays sometimes interrupt my suspension of disbelief just by being so stylistically interesting.

I always felt that my challenge was to make my little paper characters live in the reader’s mind. Too handsome images can be a distraction. When I read Gasoline Alley, I always prefer the workaday dailies. The Sundays sometimes interrupt my suspension of disbelief just by being so stylistically interesting.

I guess what struck me about that panel was that it was uncharacteristically ‘poetic’, as if you for once ease your grip and let the drawing resonate.

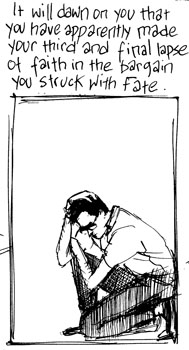

You’re forgetting that the crux of How to Be an Artist, the hinge upon which the whole book turns to face its conclusion, is an extremely poetic moment, both verbally and pictorially (since you are separating the elements here). Beginning with the third and final lapse of faith in the bargain made with Fate (the crushing void of space around MacGarry in that central panel on page 294) with Skeezix, Terry Lee and Krazy Kat then all doing walk-ons (‘walk’ literally, compare the motifs in pan 2 and pan 9 of page 295), with MacGarry by contrast dormant until Fate animates his rigid form by dripping molten silver on his head from a Coconino moon (while he is sleeping at the turnpike no less).

Sorry, I didn’t mean to suggest that there was no poetry in your work – the poetry is one of the reasons I like it so much! It was merely that that particular panel in that sequence seemed uncharacteristic in context and therefore stood out, prompting my inquiry.

We’ll rub a hole in that panel if we pay it any more attention. :)

We’ll rub a hole in that panel if we pay it any more attention. :)

[Laughs] I definitely see what you mean about cliché though, but then in After the Snooter you have a couple of silent passages when you slip into internal, symbolic sequences. This seems a departure from your earlier work, and anticipates some of the choices you make in Fate of the Artist. Could you talk about your motivations for this?

There are always going-backs of course, reversions to see if I missed something. I’m always wrestling with problems on the conceptual level of the art of making a comic strip. Sometimes I follow a thought as far as it can go. I come up against a block and have to trot back to an earlier position and pick up the thread.

I’m talking about my best work there, the Alec books. Otherwise, I can get all that old-fashioned action stuff out of my system by doing a book like Batman: The Order of Beasts, or The Black Diamond Detective Agency. But with my personal books, I’m trying to be pure.

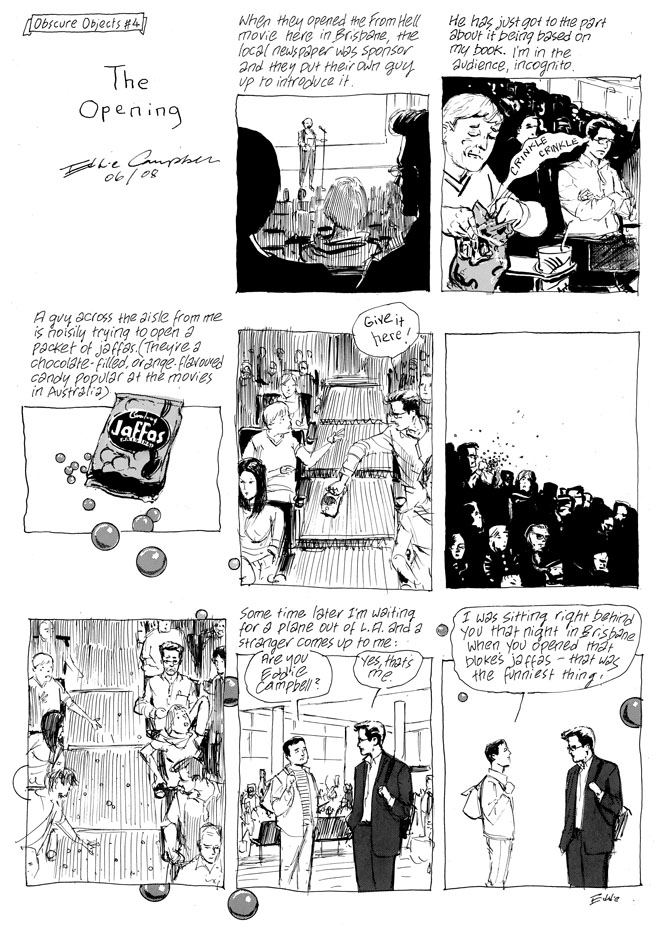

On the other hand, looking through Pants I’ve just fastened on a panel relevant to the discussion of silent panels. Panel 6 on page 618:

…one of the new pages drawn for the book. I drew that thing several times, and it even had a caption at one point. But there it is frozen in its silent glory. Alec opens a tough bag of sweets at the cinema. A rare instance when I appear to have done a whole page just to set up that silent panel.

Worth capturing

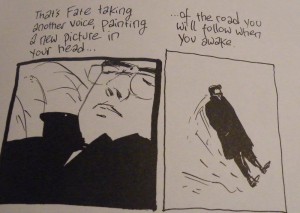

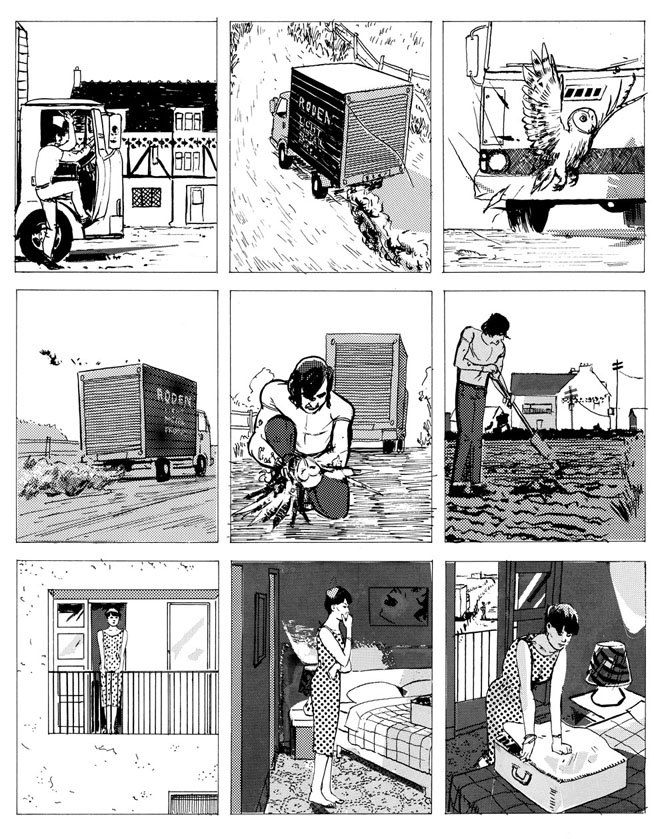

Those sequences in Snooter are dealing with inner life, in this case semi-awake dreaming I guess, in a fairly expressive manner:

This is something you hadn’t done all that much of before in the Alec stories, which leads to a more basic question: with a few notable exceptions – parts of Graffiti Kitchen and Fate of the Artist – you seem to avoid addressing moments of strong emotion, preferring to suggest your character’s emotional life subtly in his narration and, in the images, through observation – I’m thinking here in particular about the retrospective undercurrent and lingering despair in the margins of Snooter. This runs counter to a lot of comics autobiography where the extremes of their author’s experience often take center stage. What are your thoughts on this?

Of course, I’m Scottish, as you know, and we don’t do emotion. I’m reserving the emotional thing for some real catastrophe (there might be some raw emotion in my book about money that I’m working on). All through this endeavor I’ve had the idea that by the end of it I would like to have covered the whole spectrum of life in our times. I don’t mean I want to dig into all the dark corners of experience. I’ll leave that to Alan. But rather that the commonplace life is a thing worth capturing. That’s why I referenced Gasoline Alley in my introduction. What is interesting about life at 20, at 40, at 50? etc. In theory anyway, it’s a goal. I often have readers say they liked The King Canute Crowd, but that things tend to slope off after that. Then they come back after a few years and say they missed half of what The Snooter was about the first time around. Which is another reason why I avoid making up stuff, since I need the work to hang around for a long time. The bogus parts look pretty obvious after a few years.

Purity or not, your prose style is so distinct, and I find passages not only in the earlier work, but in After the Snooter that seem to me fully as wrought as the “turnpike” line. This is not a criticism – I think it is part of what makes your storytelling voice so compelling, this intermittently poetic, if also often straightforward or ironic, approach to the mundane. Any thoughts on this?

Just yesterday I took a few lines out of the thing I’m working on, because they sounded just like the self-conscious Alec MacGarry narration of the Canute years. It took me a few minutes to figure out that that’s what was bothering me about them. There’s nothing like hearing my lines quoted back at me, as my wife often does, to make me go off them very quickly. The ones I’m happiest with are usually phrases that I dropped by accident when I was in the right mood. A lot of my stuff does look caption-heavy when you skim through the book, but it would be difficult to reduce any of it. It’s all contributing vital information. If Alan had used captions in From Hell we could have wrapped the job up in nine months.

It’s not so much that the use of captions feels heavy to me, but rather that they tend to steer the narrative considerably more than the images, which accent, deepen or provide counterpoint. Is there some sense that the images, left to their own, would risk skewing the narrative toward a more ‘seductive’ register? In some ways, Fate takes more risks in this respect.

Yes, Fate is my only personal book where I let single pictures fill up whole pages. Other than that however, way back in the 1970s I felt that comic books had become these fat ugly things that wallowed in bad drawing. I rejected them then and I do so even more vehemently now. At that same time I discovered the old strips of Noel Sickles and Roy Crane. (Matt Seneca’s review of the Buz Sawyer reprint at The Comics Journal yesterday just reminded me of this: “During the frequent artistic high points, the panels are suffused in a glossy, bracingly realistic natural light…”) And I thought that this was a whole other thing entirely, and I wanted to work in that idiom, with the small compact black and white drawings, but with this great sense of real sunlight created with the doubletone board technique.

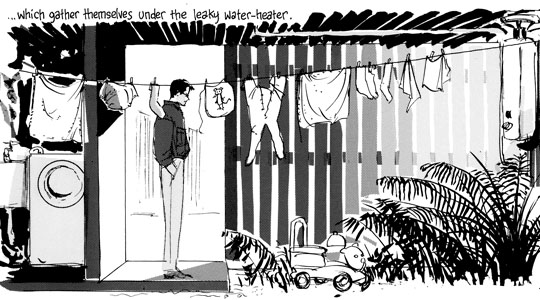

So I developed my own version of that (in the King Canute Crowd), using letratones. Putting the stuff on flat tended to kill dead any sense of light, so I cut the stuff up into fragments, letting the scraps lie at odd angles to each other. Panels 5 and 6 on page 77:

…are good examples of what I was trying to do, where I step out of the narrative for a second and enjoy the mist rising on a May Sunday morning. But it’s not obvious. I don’t make a big deal of it, but those are two little panels that succeed in taking me to another place when I look at them now. Elsewhere I might have dwelt on it more consciously, for instance the bottom panel of page 404 in The Dance of Lifey Death is a little contemplation of nature running wild under Alec’s house. If you follow the gradations of tone on the wooden fence slats, you might be pictorially astute enough to notice that I have spread out my entire range of tones from 100% black through 90%, 80%, etc down to 0 at far right.

On the whole, the reader is always aware of a hand making a drawing. It’s never reduced to the hieroglyphic manner of Nancy or some of the other newspaper funnies, not that there’s anything wrong with that. But the reader is always aware of a hands-on event taking place. There are many places where I’ve done a whole scene because I wanted to draw one thing, but I usually disguise my intention. I’d feel terribly vulgar if a reader thought ‘ah, there’s the money shot!’

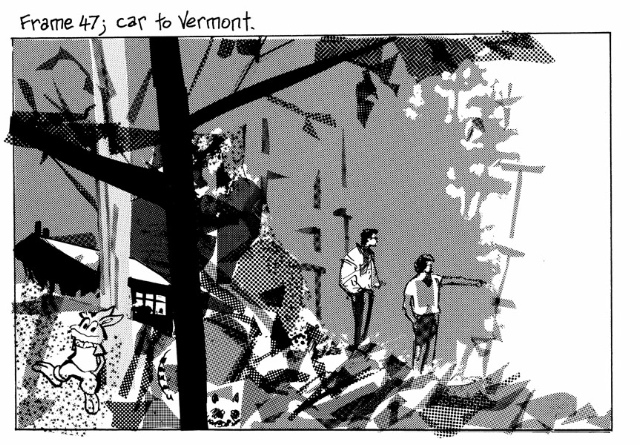

Your visual-verbal register is, I guess, largely an attempt at realism, but your use of letratone makes me think of the way comics historically have often achieved naturalistic effect through abstraction – the dark winter sky in Canute on p. 51, for example, or the Vermont landscape in The Dance of Lifey Death, on p. 370, are fairly abstract suggestions of real phenomena.

I suppose you feel your way towards an equilibrium between such instances and more barebones linework, or images making direct of symbolic imagery to illustrate concepts, and I guess the use of color and the opening up of the images in Fate was a challenge to whatever equilibrium you had built? Comics seem to accommodate a fairly wide range of approaches without too much difficulty, but it still can’t be easy to make things cohere seamlessly.

Having set my course I have to keep coming up with little pictures and every one of them has to be different from all the little pictures that have preceded it. And every page has to say something that hasn’t already been said. The techniques used in Fate certainly point me in a new direction. My next book in the autobiographical mode, if we are agreeing to call it that, is in colour and I’m producing it mostly on the computer.

I wanted to ask you about irony. It’s a big part of your humor and, consequently, your self-representation. It seems to me a risky approach when striving for authenticity, and it is, I’m sure, hard to control how people take it?

I don’t think of irony consciously, but I do scrutinize my writing like it’s a legal document before I let it go. Does this phrase leave me open to such and such an interpretation, does that one contradict my earlier position, does this other one cut the matter finely enough? I’ll tweak it to add a mischievous note, but over-tweaking introduces the danger of a formality creeping in. I see that in my old blog when I find myself re-reading parts of it. One’s audience is so widespread nowadays, and its educational status widely varied, that pinning down all the possible misinterpretations can wind up piling extra hours onto the job. I also find that humor itself is complicated. I know well-educated people who have a very primitive sense of humor.

But it’s one of those things where people always think it’s the other person who hasn’t got it. I read a review of Fate of the Artist, which emphatically declared that Honeybee was not funny in the least. Since it was essential that it should be funny, being the work of A. Humorist, whose ironic tale ends the whole shebang, I obviously wasn’t getting five stars from him. In fact, I think of myself specifically as a humorist, but I so often find myself out of tune with what passes for humor today. Myself, I can sit through a half hour (well I can’t literally) of stand-up comedy in a wretched state of dismay. I understand that to amuse a room full of average citizens requires sticking to a very obvious line of quips. If there were fewer of these citizens you could just get them on the floor and tickle them I suppose.

It seems clear that a lot of your work derives quite directly from oral joke- or storytelling, not the least the gag strip. Why do you consider that in some ways quite strongly determined format to work better for your representation of daily life than the literary register that you seek to purge from your work?

Did I say purge? These things change from phase to phase. With the Snooter book, which appeared piecemeal as it was being drawn, I wanted to have it both ways, which is to say that I wanted the spontaneous quality of ‘something funny happened today,’ like you get from [James] Kochalka’s diary comics, in the way that James studiously avoids any hint of continuity. I wanted to do that but also have a big mosaic of pieces at the end of it. So going in I had no idea how or if it would end, except that a storyteller worth his salt always finds a way of wrapping things up before closing time.

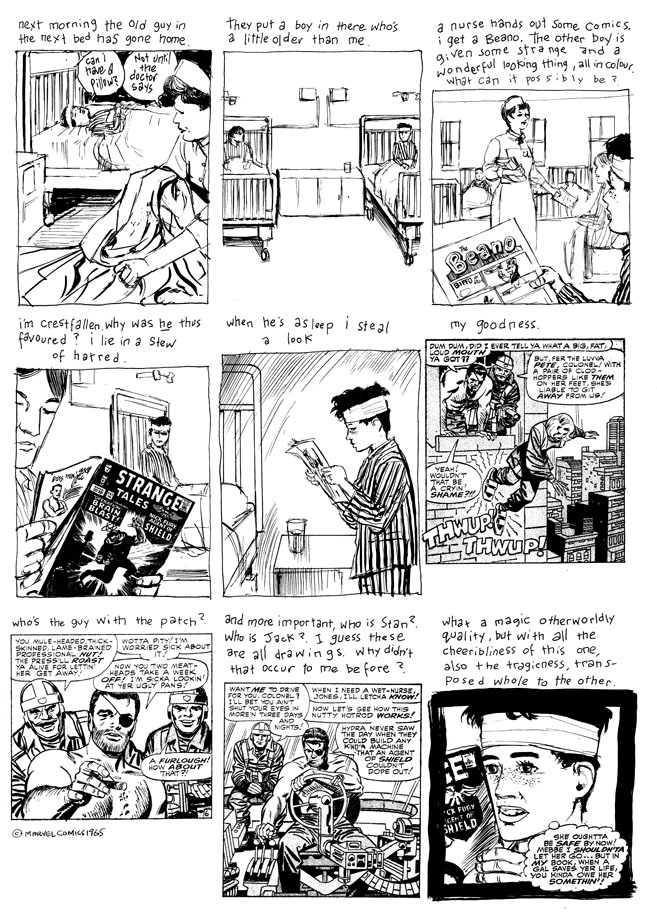

Anyway, my point is that there is a quality about improvising humour from day to day that can’t be manufactured in a looking-back kind of way. But at the same time, interspersed among that, I was looking back at childhood memory for about thirty pages if you add them all up. I hadn’t done childhood before that, I mean from the inside, first person, if you think about it, except for a brief one-page interlude in The King Canute book.

Another thing about oral storytelling; whenever I’m put in the position of giving advice to a student comics artist, I always say, tell your story orally to one or more people first. That way you’ll quickly figure out how the ‘timing’ needs to work. Then when you draw it you have to figure out something that is graphically analogous to real timing. There’s one page, in the ‘Fragments’ section of the Pants book, which appeared in The Australian newspaper’s magazine section in the week that the Melbourne Writer’s festival was giving the ‘graphic novel’ a guest-spot. The editor is a lady who interviewed me for a huge big tabloid profile-spread ten years ago and figured I could do a colour page for her that would fit the requirements and subject. Anyway, time was tight and I had to call back in a few hours and tell my piece over the phone, which is unnerving, as you can’t see how it’s going down, and there was a nice piece of cash involved. ‘That’ll work’ she said and I was in. So oral storytelling is a useful skill apart from being an aesthetic position.

High/Low

Stepping back a bit: you’ve emphasized often enough your interest in early modern cartooning and the visual-verbal vernacular it developed, and it’s clear that your work is informed by it. At the same time, of course, Alec is clearly a project with high art connotations. What is your take on the dissolution of modernity’s hierarchical structures of high and low culture and what’s the potential of comics in that context, now that they are increasingly integrating high art registers?

The problem with the dissolution of the high/low hierarchy is that it’s been replaced by communities. And each community goes to great lengths to define itself and repel boarders. So they establish definitions. Thus you find, last week when Shaun Tan’s film won an Oscar, on The Beat’s news site:

“Whatever you thought of the hosts, the win in the Best Animated Short Film for Shaun Tan …was a nice win for a very talented artist. Although the Australian Tan is more of an illustrator than a cartoonist, his best known work, THE ARRIVAL, is certainly an example of graphic storytelling — so if he isn’t exactly on our team, he’s pretty darned close.”

So we have ‘Team Comics,’ which is defined by its geekiness. Just a few days earlier, the recommendation for Lady Gaga’s latest video had a different tone:

“Lady Gaga’s nerd-friendly world…If you like Fritz Lang, Giger, Superman, Sin City and Bernard Herrmann, you are sure to like this short SF film!”

I much preferred the old High/low thing. On the other hand, I’m not sure I agree with the ‘high art connotations’ in that my work, however intellectual it gets, is still always ‘about something.’ It is illustration in other words, and that has for a century and a half run in a contrary direction to ‘high art.’

So, when you say you hope to represent the entirety of life, you don’t think that’s a high art ambition? I know there has been Gasoline Alley, but largely that’s been the domain of literature, right?

I wrote something here then deleted it. I really don’t know any more. ‘High art,’ ‘literary’… these kinds of frames are usually describing our relationship to something rather than the thing itself. And Gasoline Alley might be confusing the picture here. That’s a depiction of a pleasant ordinary ‘everyday’ in small town America like you might have heard on the radio. In the context of our current overblown comic books it appeals for its ordinariness and also it represents America’s view of itself in a time and place. If I used the word ‘entirety’, I meant let’s not leave out the commonplace.

OK, this notion of illustration then: do you mean your comics are illustration or that your drawings illustrate your text, or rather – the ‘literary’ writing behind it?

In the larger world of art, anything representational is seen as illustrating something other than itself. A painting of two people talking illustrates a conversation. A picture of a bowl of flowers is an illustration of a bowl of flowers. A painting that has no relationship to anything in the real world however, is pure and escapes from the supposed taint of illustration. Pure painting is not representational. (Even something like Lichtenstein, a discussion of whom both you and I got involved in a couple of years back: his picture of a girl with a tear in her eye is not an illustration of a weeping girl in the same way that the source panel from the comic book is… but that’s an argument for another day…) I’m always illustrating something, so I can’t imagine my work ever being discussed in a conventional fine art context. There would have to be a rather dramatic change in the game for that to happen.

In a narrower context, illustration is making pictures to order for commercial purposes. In an infinitesimally small context, illustration is saying one thing in a caption and same thing in the drawing that it is attached to. In an even more conservative version of that, it’s crafting the picture into a very attractive representation of the thing it is describing, more attractive than is theoretically necessary. A hundred and fifty years ago, being well read was considered a good thing to be, therefore pictorial art that referred to scenes from books (e.g. the Pre-Raphaelites and their contemporaries) was held in high regard, and in due course there was a golden age of illustration that gave us people like Norman Rockwell. But the literary establishment came to see illustration as a low thing, because it corrupted the primacy of the word. That’s not even a Victorian thing, because the Victorian era was the great age of illustration, but a later superiority that crept into literary establishment. The theory was conceived that it stunted the imagination of the young.

This of course is nuts. I often look at the ease with which old-time illustrators drew the rigging in an old ship, or something equivalent to the remoteness of that from our own experience. How could you ever know about something like that unless you see it in a picture (short of seeing it in life of course, always preferable)? To tell somebody that they have to imagine it is willfully illogical. But that is the tenor of the age we grew up in and the residue of which we still find ourselves confronted with. (In the one-year foundation course in art I did at college I was horrified when they realized they were going to have to give us a lesson in perspective, because only half a dozen people in the class knew anything about it. Representational drawing had fallen so low, but this is something I smile at when I still hear some old codgers complain about it)(maybe you just did :) ). The lowest of all arts is the one that is made up entirely of illustration, the one that we are discussing. There used to be something raffish about the contrariness of that. There isn’t any more, which depresses me. But if I think about it too much I’ll go mad. Which is not to say I haven’t already.

I hear you, but I’m not sure I follow entirely: the visual fine arts historically have been and continue to be representational in large measure, and aren’t we, in fact, seeing this rather dramatic shift taking place, where comics are being discussed increasingly in such a context? And couldn’t one make the argument that your comics contributed toward this shift? I mean, the Alec stories explicitly champion comics as an art form, From Hell does it at least implicitly, even Bacchus has that subtext. I guess what I’m trying to get at is your notion of what comics have to offer as an art form, and how they might derive and realize such potential precisely because of their lowbrow history. Is your point that such terminology gets in the way of the “thing itself” – and if so, what framework would you prefer for the discussion of it?

We’re discussing it seriously here, but in the world out there I’m concerned that what has happened is that the culture at large has, instead of leveling out the high/low thing, plunged to the level of comic books. So I don’t think there is a fine art to aspire to any more, except insomuch as one might aspire to live in a bygone age. Good work happens wherever it happens. There are no ‘art forms.’ The best work happens independently of that. Think of Tom Phillips’ The Humument or Graham Rawle’s Woman’s World. And as for comics, they start to interest me somewhere after the point where they stop being comics. Apart from the very old stuff of course. I’ll always have a fondness for the classics.

The high/low thing has been replaced in the present-day by an obsession with categories and genres and trying to draw lines of demarcation and hold everybody to them. You get articles around the comics net in which writers try to figure out what exactly a comic is, and what qualifies and doesn’t qualify. Order is wanting and people will make up some system of order rather than face having to get along without it. Now we no longer say ‘Is it art?’ or ‘is it literature?’ We say, ‘yes but is The Arrival comics?’ or ‘is Vonnegut science fiction,’ or ‘the graphic novel is not a genre, it’s a format,’ or ‘This isn’t gangsta rap, it’s crunk.’

Also, in my experience, anyone who describes themselves as a “fine artist” usually turns out to be an idiot.

Disappearance

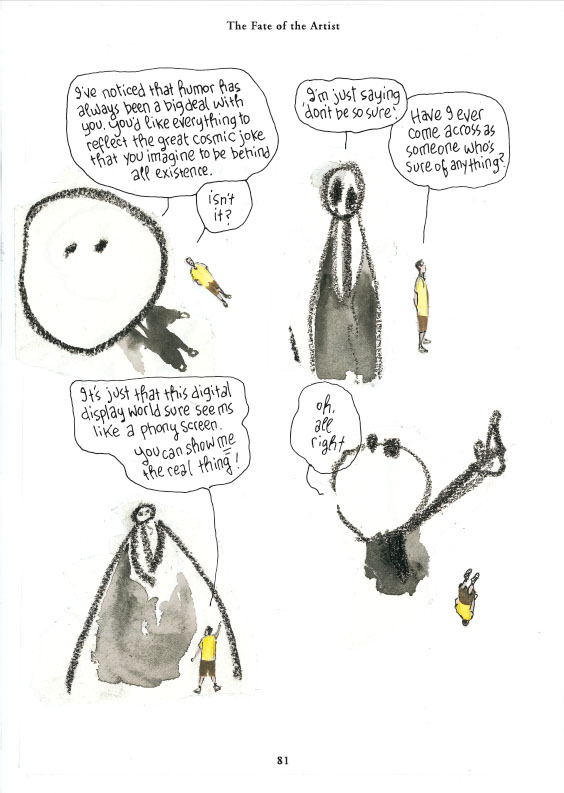

From Alec McGarry to the disappeared Artist, your central character has always been an unstable entity, and you’ve moved toward fairly extreme dissolution in Fate of the Artist, which sees theoretical concerns take over what has generally been, or at least felt like, a fairly realistic, accessible narrative in earlier books. The book evinces a tension in the work that one realizes was there all along, but less foregrounded. Where does this tension come from, and did you find it impossible to proceed without addressing it?

I’m guessing you mean the idea of art and MacGarry’s relationship to that. As early as page 68 in the Pants book there’s a direct reference to this, although prior to that we would always be presuming that he had some other agenda above working in a factory. In Graffiti Kitchen it’s there, but there’s always a certain cynical caution about the subject. By the end of How to Be an Artist, the disappointments are accumulating. Fate of the Artist is a full-fledged attempt to bail out. Perhaps he would like to turn back the clock to the years of, in the words of Nietsche, “…that happy state in which one does not yet know the limits of one’s gifts and thinks that all objects of love are attainable.”

CARO: Both How to Be and Artist and Fate of the Artist are very concerned with influence, but How to Be an Artist references are much more overtly to comics history than Fate’s, which reference art and film and literature. The influences in Fate seem much more distant than those in How to Be an Artist; there’s no image of you knocking on the door of the Petersplatz or the Globe. The story of the CDs implies a deep investment in music, but it’s still depicted with distance, due to the conceit of the author being missing. The effect of reading them back-to-back is that affectionate intimacy of your relationship with comics comes across really strongly. The pan-arts references in Fate are something I really like about the book, but do you think you could have written Fate referencing the history of comics in the places that you referenced the history of the other arts, or was it essential to you to cast a wider net?

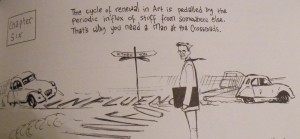

In How to Be an Artist the idea was to present comics as an art to stand in for all arts. The book was in the form of a comic and it was relevant to use the history of that idiom. But I’m interested in art as a whole. And on page 298 I let R.G. Collingwood make it clear on my behalf: “The story is the same whether we look at Samian pottery or Anglian carving, Elizabethan drama or Venetian painting…” In Fate I wanted to develop the theme further. In the interim since I had started How to Be an Artist (1996), I had become more consciously interested in postmodernism. This consciousness began with a chap who wrote his university thesis on aspects of postmodernism in my autobiographical work. I got to thinking, ‘hey, I better look into this whole thing, check out some of these texts I keep stumbling upon.’ No big surprises, as I think I must have breathed in a lot of information without being aware of it, but this did help me out of an impasse. I had started writing Fate as a prose novel, believe it or not, which is the point here. It wasn’t a comic, so my affection for comics wasn’t going to be relevant to it, in answer that part of your question. And during this time I had been keeping the roof on the house by doing Batman and other superhero things, not all of which were mentioned by Alex Boney the other day. But I was having trouble writing in a voice that didn’t sound bogus. In fact most fiction sounds bogus to me. I can rarely get past reading the first page of other people’s novels. So I let it be bogus and threw in a lot of other bogus pastiche stuff, even using O. Henry’s voice to say what I wanted to say, and the thing ended up being another big complicated comic, but that is the odd direction by which I arrived at it. My own voice is a visual/verbal one I guess.

CARO: Fate opens up a nice double entendre in the title (the kind that would have been immediately obvious if it were in French): it’s both the artist’s fate and artistic “fate”, both “the fate of the artist” and “the kind of fate appropriate to the artist.” And that “fate” appropriate to the artist is a chaos, held together with a paperclip (the paperclip on the toilet, the paperclip on the brick). So there’s a really nice synergy between the “not very tightly held together” chaotic universe and the “not very tightly held together” artistic identity. And Evans’ desire for control is, in the end, what kills the artist off.

The book itself is pretty tight conceptually, though, even though you do a great job of making it seem insouciant. There’s this cluster of contradictory things at the center of this view of art, which is why, I think, it’s so compelling as art to me. Re-reading this immediately after How to Be an Artist, though, where “fate” was more a motivating force that you had to submit to, I wonder how much the idea of submission to chaos, not trying to control, is meant as advice, a philosophical assertion of how to approach making and taking in art.

The dichotomy is between the arts on the one hand and the sciences and other more logical disciplines on the other. Once again, R.G. Collingwood: “To the historian accustomed to studying the growth of scientific or philosophical knowledge, the history of art represents a painful and disquieting spectacle.” That one line expresses my overriding theme in all of these books. In our own time this spectacle consists of the upsetting of the traditional high art/low art balance. Campbell’s issue with this is that he thought this meant that comics would be accepted as a medium, with its particular forms, and also with its rich background of having evolved through its Kings, Herrimans and Caniffs, etc., etc., but what has actually happened is that the whole geek thing has prevailed and we have a huge proportion of the movies coming out of Hollywood being based on superhero comics, or they might as well be, and genius-grant-winning novelists writing issues of superhero comics. And fine art, somehow missing the fact it’s now on a level field, is still appropriating crap all over the place with all the imagination of tribute bands. It’s such a crushing disappointment, the whole current artistic landscape. Things didn’t turn out as I dreamed they might have. The potential satisfactions perceived at the outset have disappeared in the reshuffling.

I didn’t exactly say that in Fate, as ordinary readers are unlikely to know what I’m talking about (he gets to draw pictures for a living; what’s he got to complain about?). So I went for a more conventional and more entertaining malaise, the problem of being a vampire in my use of living people in my work, a thing which does worry me from time, and its accessible. And it’s not like I’ve thrown in a bottle of magic absinthe. And knowing that was the conclusion, I built the book toward that. But in a much more general sense, and I think this should come across in the work, the idea of art and being an artist never pays off in the way we imagined it would. (Hence my forays into history in Fate). For every Shakespeare or Mozart there’s a Louis Gabriel Guillemain who wanted out of the world enough to stab himself fourteen times before expiring, or a Henri Duparc, a composer who destroyed all his work except for a dozen songs that escaped from him and you can find on one CD, who wrote in a letter to a friend: “Having lived 25 years in a splendid dream, the whole idea of [musical] representation has become – I repeat to you – repugnant. The other reason for this destruction, which I do not regret, was the complete moral transformation that God imposed on me 20 years ago and which, in a single minute, obliterated all of my past life. Since then, [my opera] Roussalka, not having any connection with my new life, should no longer exist.” So there’s also a mysterious psychological element to investigate. But that’s perhaps for a future project. Fate exhausts the theme for now, and my next book, which I’ve nearly finished, will be all about money, you’ll be glad to hear.

It seems clear that Fate is your most complex effort so far to step outside yourself and to go beyond the already fairly complex set of narrative registers you’d operated on up till then, i.e. the narrator in the captions, the Alec character who morphs into Eddie in Snooter, the different versions of same that appear occasionally, the intermittent spilling over of inner (verbal) monologue into symbolic imagery, etc. An attempt to suppress that, while acknowledging the inescapable presence of you as an author – did you have a concern that your work might otherwise risk solipsism?

To avoid tipping over into insanity I should think. How sane that fellow looks, at the end of Fate, now that he has managed to escape from himself. I guess he was doing it by increments over the years. I see what you mean though. Even in fairly straightforward sequences there was often a switching from third to first person, long before I complicated it by introducing the second person, and from past to present tense, before I threw in the future. Occasionally I would catch myself doing those first/third changes and past/present and then wonder whether I should leave it or change it. I’d scour assorted literary works to catch the masters doing it. It’s everywhere in Henry Miller, so I figured that it must have been debated already as much as it needs to be debated. So the authorial identity uncertainties were part of the prevailing neurosis of my oeuvre before I threw MacGarry out altogether.

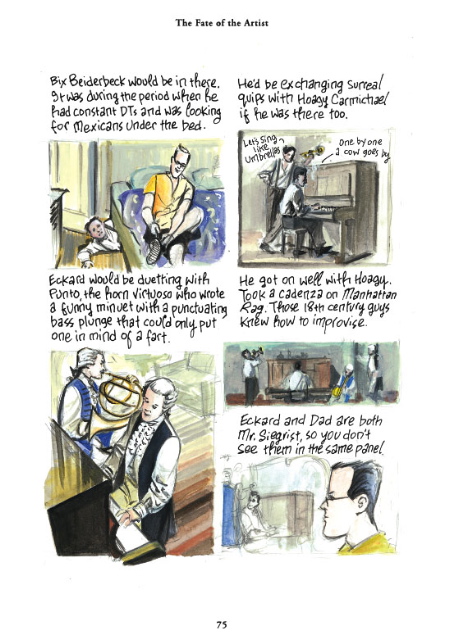

The next step was to cast the actor Richard Siegrist in my place. I didn’t develop this as there was already too much in the book already, so it remains an extra-textual thing that never got invited in. Somewhere in all my files and collection of old jazz music, the name Siegrist appears as a confusion of Secrest. Andy Secrest was a trumpet player who as a young man fell under the influence and artistic spell of the great Bix Beiderbecke (who pops up on page 75 of Fate as one of the author’s circle of imaginary friends… to the true inhabitant of the imaginary realm, one’s heroes are really in the room), and who got his first big break in music by subbing for Bix in the Paul Whiteman orchestra. By all accounts, he was an amiable chap whom everybody liked, including Bix. An Italian film-maker, Pupi Avati, made a drama-biopic of Bix’s life in 1991, which I haven’t seen (trailer).

This relates to what I was saying earlier about movies and ‘there can be no drama without conflict.’ In the same way that Salieri was made the envious villain in the life of Mozart first through Pushkin’s drama Mozart and Salieri of 1831, an apparent falsehood perpetuated all the way through through Shaeffer’s play, Amadeus of 1979. In the same way, the innocent Secrest was cast as a scheming and jealous rival to Bix in Pupi’s film (so I have read). You can see how this relates to my thesis about the artist’s fate being in the hands of an unreasonable world. I satirized the absurdity of this baloney in Fate by having author Campbell murdered by his book-designer, Evans. I even describe the body ‘double-bagged.’ Since he wasn’t in fact murdered, obviously, all the other suppositions must also fall apart.

The funny part about it really is that this murder was an addition that I put in at the twelfth hour because my editor, Mark Siegel, felt that the drama of the book had been left unresolved. And funnier still, the designer, who was the last to handle the digital files, wreaked his own vengeance by salting away a secret message in the small print on page 46 of Fate, which wasn’t discovered till after the book was printed. I turned the story of this conflict into a stand-up comedy performance, which was filmed in Chicago by Bookslut. All of this is a huge self-indulgence unless we allow that it illustrates my point about the artist’s fate being swallowed in a vortex of untruths that are superfluous to the simple facts of his short time on the planet. And if you shouted ‘Self-indulgence!!’, I can only wonder at how you got all the way to the end of a huge interview with an author about his 640-page autobiographical comic. [Matthias laughs].

_______________

The entire roundtable on The Years Have Pants is here.

In addition, our colleagues at the Panelists held a simultaneous roundtable on Campbell, focusing especially on the Playwright but touching several other works as well. Their roundtable is here.