Over the last few months I’ve been doing an occasional series on the feminist limitations of an ideology of empowerment. My argument has been that a feminism obsessed with power is a feminism that is indistinguishable in crucial respects from patriarchy. It’s also a feminism that tends to reject parts of women’s experiences out of hand. Domesticity, children, family, peace, selflessness, love, and even sisterhood can be tossed by the wayside in the pursuit of an ideally actualized uberwoman valiantly and violently staking vampires or what have you. And as for those who are not ideally actualized — well, for them, empowerment feminism often offers little but contempt and dismissal.

Over the last few months I’ve been doing an occasional series on the feminist limitations of an ideology of empowerment. My argument has been that a feminism obsessed with power is a feminism that is indistinguishable in crucial respects from patriarchy. It’s also a feminism that tends to reject parts of women’s experiences out of hand. Domesticity, children, family, peace, selflessness, love, and even sisterhood can be tossed by the wayside in the pursuit of an ideally actualized uberwoman valiantly and violently staking vampires or what have you. And as for those who are not ideally actualized — well, for them, empowerment feminism often offers little but contempt and dismissal.

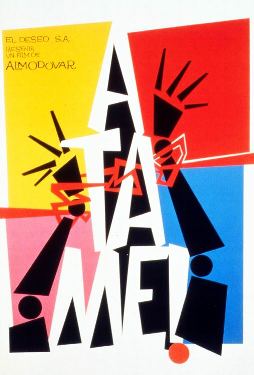

I still believe all that. But…well. If anything could convince me otherwise, I think it’s Pedro Almodovar’s “Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!”. Mostly because, after watching it, I would like to see a passel of empowered feminists kick the director’s sorry ass.

As I am not the first to notice, “Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!” is an intentional, sneering, anti-feminist provocation. Ostensibly, it’s a romantic comedy featuring Antonio Banderas as the adorably amoral ingenue Ricky. Ricky is released from the mental hospital at the film’s beginning, and immediately goes off to kidnap former porn star and drug addict Marina (Victoria Abril). After hitting her in the jaw, he traps her in her apartment and tells her that she is going to fall in love with him and that they’ll then go off and have lots of babies. At first she is incredulous, but then he steals painkillers for her and gets beaten up for his efforts and she realizes that he really does love her…and so she falls for him and they have fantastic sex and then they ride off into the sunset to live happily ever after. Aww.

Like I’ve said, I’ve written a lot in this series about how a feminist text does not have to present women as perfectly empowered, and about how building your life around love is a really reasonable choice. So Marina is not perfectly empowered, and she chooses love. What’s wrong with that?

What’s wrong with that, I’d argue is that I don’t believe Marina is actually choosing love. That’s first of all because I don’t believe in the love. In a good romantic comedy, you need to become a little bit infatuated — or more than a little bit infatuated — with the leads. I don’t necessarily want to marry Cary Grant’s bumbling doofus, but he’s vulnerable and, contradictorily, witty enough that I can see why Katherine Hepburn would. Darcy is almost lovable just on the strength of his having the good sense to fall in love with Elizabeth, but if that weren’t enough, his competence and determination to help not her, but her whole family, certainly seals the deal. Even that bone-headed drama-queen Edward, so desperately trying to be cool and dangerous and so obviously a raging mass of hormones and stupidity trying incompetently to impress and care for the girl he loves — I can see the appeal.

But Ricky? What is there to like about Ricky? I know Edward is supposed to be all stalkery and abusive, but Ricky is actually, literally a stalker and abuser, tracking down a woman he barely knows (they had a one night stand at some point, apparently), hitting her, and threatening to kill her. He constantly engages in petty crimes, shaking down a drug dealer or stealing a car, and while I guess that’s supposed to make him dangerous and cool, in truth it just makes him seem like an untrustworthy thug. Even his tragic backstory (he lost his parents young or some such rot) seems like rote, tedious whining. His bland confidence that he’ll get what he wants; his noxious self-pity (he constantly chastises his kidnap victim for her selfishness and for not seeing how hard things are for him; his vapid cruelty — I mean, I know he’s Antonio Banderas with movie star good looks, but come on. He’s a charmless cad.

Lots of women (and lot of men, for that matter) do in fact date charmless cads — though even the most charmless cad doesn’t generally begin the relationship with battery and kidnapping. But, in any case, I don’t believe Marina is one of those women who dates charmless cads, because, just as I don’t believe in her love, I don’t believe in her. She’s not a real woman — or even a representation of a real woman. She’s got more in common with Pussy Galore than with Hepburn in Bringing Up Baby or Elizabeth in Pride and Prejudice or even with Bella. She’s an instrumental fantasy of compliance — which is why her sexual dalliance with a child’s bath toy is what passes for character development. She is there to experience a conversion rape, and the conversion rape is all she is.

Almodovar is perfectly aware of this; in fact, he smirks about it. I mentioned that Marina is a former porn actor. She left porn to star in a exploitation film directed by the great director Maximo Espejo(Franisco Rabal) — roughly translated as “maximum mirror”. Maximo is aging, wheelchair bound, and impotent — he has hired Marina, the film makes explicit (literally in a sequence where Maximo watches one of her old films) because he finds her sexually attractive. The movie doesn’t find this icky, though, Instead, we’re invited to see Maximo’s impotence as a tragedy of genius. His crude comments, directed at both Marina and her sister, are supposed to be cute, just like Ricky’s naive egocentrism and sexual brutality is supposed to be charming. For the last scene of his film, Maximo orders Marian to be tied up and dangled from a window…a motif prefiguring her “relatonship” with Ricky. Ricky, then, becomes, and none too subtly, the director’s avatar, dominating and fucking Marina as Maximo cannot. It’s all just a harmless fantasy, isn’t it? Who are we to deny a genius his stroke material?

Almodovar is gay, of course, so his exact investment in the fantasy is a little unclear. You’re supposed to see him in part as Maximo the mirror, the watcher enjoying or manipulating the tryst. But even if what we have is a coded gay parable about embracing your forbidden love by fucking Antonio Banderas, the fact remains (and is even underlined) that Marina as a woman, and Marina’s desires, are, for the film, utterly irrelevant. It’s not a question of Marina being empowered or disempowered, or even a question of Marina being a blank (as Melinda Beasi recently said of Bella in the Twilight graphic novels.) In fact, it’s not a question at all. The movie simply doesn’t give a crap about Marina. She’s a marker in someone else’s story — which is maybe why she only actually seems to come alive during the film’s much-ballyhooed sex scene. Laughing and animated, she turns over and over with her lover/cad, begging him not to let his penis fall out of her. It’s like Almodovar can only imagine her as interesting, or human, when she’s got a dick.

I did just say in that last paragraph that it’s not about being empowered or disempowered — but I think that’s probably a cop out. The film is, after all, a two-hour paen to the joys of stalking and domestic abuse. It’s a useful reminder to me, perhaps, that one reason men advocate disempowerment for women is that they get off on it. Feminists have every reason to distrust them.