Dark Knight Rises is an odd movie. It’s a mish-mash of Dickens, adventure stories, geek nostalgia, Hollywood bombast, and a smattering of “ripped from the headlines” topicality. The movie manages to be a fairly enjoyable diversion, but as other reviewers have noted, it’s a mess from both a narrative and ideological perspective. But its messiness isn’t entirely the fault of the filmmakers. The latest film is part of a decades-long process where a children’s adventure story was modified to appeal to an older audience, specifically an audience that remained attached to the childish elements of the story. Live-action Batman films (and TV) are required to satisfy both a nostalgic attachment to childish adventure stories while insisting that such entertainment is not childish.

In ancient times (i.e., before I was born) live-action Batman was a simple concept. No one would accuse the original Batman series (1966-68) of being too complicated. It was children’s television at its most basic: bright colors, catchy music, unvarnished plots, and violence that never went beyond a punch to the jaw. The series had no pretensions of being either great art or politically relevant, which is not to say that it was bad. In fact, Batman was and is consistently entertaining. The over-the-top performances of the villains, the deadpan earnestness of Adam West, and the 60’s camp were successfully mixed with the more ridiculous premises from the comics. But while the series became a cult classic, it had its share of detractors. Its unabashed silliness was less appreciated by the aging community of comic fanboys who wanted their Batman stories to cater to their adult tastes.

Comic book Batman entered a “grim and gritty” phase during the 1980s, and this was reflected in Tim Burton’s Batman (1989). Significantly darker and more violent than the TV series, the movie was clearly targeted at an older fanbase. It was also the first attempt to turn Batman into a Hollywood blockbuster, along the lines of Jaws or Star Wars. Blockbuster status meant lavish production values, fancy special effects (which haven’t aged well), marketing deals with fast food chains, and an A-list cast, including Michael Keaton, Kim Basinger, and Jack Nicholson. But the childish elements of the character remained: the Batmobile, the Batcave, and all those “wonderful toys.” Another director might have produced an incoherent disaster, but Burton cobbled together a reasonably entertaining, if shallow, film that satisfied both the fanboys and mainstream audiences.

The secret to Burton’s success was due to his idiosyncratic vision of Gotham City, a heaping dose of film noir with a touch of BDSM and goth sub-culture. Batman and its sequel, Batman Returns, could be described as noir-lite, lacking most of the typical noir preoccupations but relying on dark, brooding imagery to enhance a plot that relied on mood more than substantive content. The goth and BDSM influences factors more heavily in Returns, particularly during the famous origin sequence of Catwoman. Among the many superhero film franchises, the Batman films by Burton stand out as having a distinctive look.

Burton’s idiosyncrasies allowed the various pieces of the Bat franchise to co-exist, albeit uneasily: the fanboys got their “dark” story, mainstream audiences got an action film that didn’t look like all the other action films they had already seen, and the more juvenile elements appeared slightly less ridiculous if they were bathed in shadow. But in aiming for an adult audience, Burton could never fully embrace the most childish parts of the Batman franchise. Most obviously, Robin is nowhere to be seen (to say nothing of Batgirl, Bat-Mite, or Bat Shark Repellent).

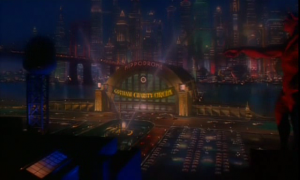

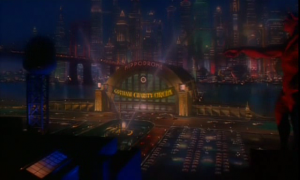

The Bat-franchise went through a number of changes with Batman Forever (1995). Officially a sequel to Batman Returns, Forever could more accurately be described as a soft reboot, given that the film had a new lead actor (Val Kilmer) and a new director, Joel Schumacher. And Schumacher’s movies had a different visual style and a greater affinity for the childish content in Batman comics. This Batman film would have a Robin (Chris O’Donnell). Gadgets and other wonderful toys would be on full display, and Schumacher even worked in a joke with the “Holy ___!” exclamations made famous by the original Robin, Burt Ward. And the dark Gotham of the Burton films was replaced by a much more vibrant and cartoony city.

But many of these features were overshadowed by the presence of Jim Carrey (as the Riddler), who was at the height of his fame when Batman Forever was released. The next film lacked Carrey and his massive ego, allowing Schumacher to shape the Batman franchise to his own preferences.

Batman and Robin (1997) is widely regarded as the worst of the Batman films, and perhaps the worst superhero movie ever made. While my inner contrarian would love to defend the film, in truth it was fairly awful. Bad acting, worse writing, and not a single moment of genuine excitement. But for many fans, the movie’s greatest sin was that it was campy. It had Batman and Robin fighting on ice skates. It had godawful puns delivered by Arnold Schwarzenegger (as Mr. Freeze). And there were nipples on the bat-suit.

Schumacher’s great mistake was in assuming that Batman was a campy character for kids (and maybe adults who enjoy children’s entertainment). It’s an honest mistake, because Batman really is a campy character for kids (and kids are still interested in Batman, as demonstrated by more than one successful animated series). But something big happened over the course of the 80’s and 90’s – fandom got older and became mainstream. And over the past two decade superheroes went from being a niche product sold to young children and antisocial geeks to being a significant chunk of Hollywood’s revenue. People who had never picked up a comic were getting excited about the latest Batman, X-Men, and Spider-man films. But the mainstreaming of superheroes meant the contradictory preoccupations of fandom – a reverence for source material with an insistence that such material be updated for an older audience – also became mainstream.

The change was driven by a number of factors. Comic nerds may be a minority, but they are disproportionately likely to have disposable income and are fiercely loyal to certain intellectual properties, two things which make them an attractive market to the Hollywood suits who own those IPs. Also, the older distinctions between “children’s entertainment” and “adult entertainment” were declining, the result of the creation of the PG-13 rating in 1986. Previously, the MPAA ratings systems drew a stark contrast between films appropriate for children (G and PG) and films restricted to adults (R) because of sex or violence. But the PG-13 rating effectively created new genre of action movie – with just enough violence and sexual content to please adult males but not so violent or sexual that parents wouldn’t allow their kids (or at least their teens) to see them. And the “grim n’ gritty” superheroes preferred by older fanboys fit perfectly into this new rating. Tim Burton seemed to understand the new approach, so he toned down the goofier aspects of Batman. Schumacher highlighted that goofiness, and the fans never forgave him.

Which leads me back to the recent trilogy of Batman films directed by Christopher Nolan: Batman Begins (2005), The Dark Knight (2008), and Dark Knight Rises (2012). Superficially, Nolan’s films are similar to Burton’s. The three movies are dark, both visually and figuratively. They were surprisingly violent, even by the standards of PG-13 movies. And many of the more juvenile elements of the Batman comics were either excised or downplayed. For example, Robin is largely absent from the trilogy (except for a brief reference at the very end of Dark Knight Rises). But the Nolan films went even further in the pursuit of seriousness. Batman was grounded in a realistic world, so his vehicles and gadgets became less fanciful and were explained away as next-gen technology (memory cloth!), persuasive to audiences as long as they don’t stop to think about it. And the outlandish versions of Gotham created by Burton and Schumacher were replaced with spliced footage from real cities such as Chicago and Pittsburgh. Nolan was also determined that his movies touch upon important current events. In other words, he wanted his films to be topical. In The Dark Knight, Batman uses an illegal surveillance system to track down the Joker, referencing the growing “surveillance state” in the U.S. and the obvious risks to civil liberties. Dark Knight Rises includes an homage to “A Tale of Two Cities,” and it’s not hard to see a link to the Occupy movement and growing inequality in the U.S.

Nolan went further than Burton in promoting Batman as a character that adults could appreciate, but at the end of the day he couldn’t ignore the childish roots. The character of Batman is still a boy’s adventure story, and the elements which make the Batman stories juvenile are the same elements that actually make them fun. So Batman still drove a rocket car, used cool (if less ostentatious) gadgets, and fought supervillains. And in the third film, Batman was flying around in a vehicle that was obviously pure fantasy, brawling with Bane, flirting with Catwoman, and prepping a would-be Robin. Altogether, Dark Knight Rises was actually rather “comic booky.” For all their pretensions at maturity, realism, and topicality, the Nolan films are still about a guy who dresses like a bat and fights supervillains.

So Batman can’t escape his goofy comic book origins. The various stabs at maturity will generally be in conflict with the juvenile appeal of superhero stories, namely the fistfights, the toys, and the empowerment fantasies. It is also extremely difficult to address political issues with any degree of nuance or intelligence, because boy’s adventure stories are not known for either of those qualities. But Batman will not be going back to the days of Adam West and the batusi. Given the huge success of the Nolan films (and the bitter hatred directed at the last Schumacher film) it’s clear that mainstream audiences have embraced the preferences of fanboys. Batman is going to be dark, violent, and pseudo-mature for the foreseeable future.