Here’s my pitch for a dystopian novel. It takes place in Wealthy Powerful Nation (WPN), a country that is secretly spying on its citizens. In fact, those citizens life in a state of near-total surveillance and don’t realize it. Or, at least, won’t admit it to themselves.

You see, that’s the weird thing about Wealthy Powerful Nation, it’s a dystopia that doesn’t look like one, because it has a number of mechanisms in place that help hide how dystopic it really is. The citizens know on some level that the world is a terrible place, but they’re also living through a time of abundant good-to-great art and entertainment available at little-to-no cost. The people live in perpetual debt to make it seem like they have a stable, middle-class life. The country supposedly has freedom of speech, but corporations own most of the venues for that speech. Freedom of assembly is guaranteed, but the government can track its citizen’s locations at all times, can turn on the cameras on their electronic devices without them knowing it and record them, and can use very powerful computers to sift through the patterns of their actions to determine what they’ll do next. There’s very little oversight for the Government of WPN, and this system of surveillance has completely coopted industry and banking. Meanwhile, WPN is able to kill pretty much anyone in the world any time it wants, using an army of flying robots.

One man, let’s call him Ed, works for the surveillance state, but he has doubts. He believes that total surveillance impacts freedom, and so he steals a vast archive of information about the system of domestic espionage that WPN employs. He flies halfway around the world to reveal this information to a team of journalists and then skips town.

When the information is finally revealed, the world responds by mocking Ed on twitter for weeks for some stupid things he says about Vladimir Putin. Gradually, opinion polls come to agree with Ed, but nothing of any consequence changes.

Not a great story, is it? Not likely to be turned into a four part movie franchise starring Chris Hemsworth. There’s a couple of reasons why it’s a lousy story. The first is that, well, there’s not a lot of hope in it, and if there’s one thing that sets apart modern day dystopian narratives from their spiritual grandfather 1984, it’s the presence of hope. Hope that the State can be defeated, hope in the future, hope in progress, and, perhaps most important of all, hope in your fellow humans.

Looking at the United States today, it’s hard to see a lot of reasons for hope, largely because there’s been so little change, despite our current President’s use of both of those words for his election campaign. For you see, unlike the characters in most dystopias, we are not exactly victims. We have chosen our leadership, whose prosecution of a global war on terror remains largely popular, except for when it can be demonstrated to harm us directly.

Lucky for us, we outsource our harm as much as possible. The people we kill live half a world away, destroyed by flying robots piloted by children in a dark room nowhere near their quarry. Our all-volunteer army pulls so heavily from specific demographic groups that many of us can go about our lives without seeing any consequence of our war if we don’t want to.

And we don’t want to, do we? Looking the demon jackal that we have summoned with our war on terror dead in the eyes would be unbearable, paralyzing. Certainly, the torture report’s breaching of my own person walls of denial was for me, even though I already knew what was in it. So we ignore the demon jackal even while feeding it ever more of our humanity, willfully joining the only conspiracy that really matters, the one of ignorance and complicity.

These are desperate, hopeless times. Desperate, hopeless times call for desperate, hopeless art forms. Perhaps this is why Joe Sacco, who has made a name for himself as a comic book journalist specializing in war reportage has turned to satire, that most desperate and hopeless of art forms, in Bumf #1, his response to America in the age of perpetual war.

Satire has lost a lot of its luster now that it’s regularly used by racists to excuse impolitic things they’ve said on twitter, but satire has performed a unique and important function since the ancient Greeks. No other genre can get as close to unspeakable truths, because satire rides there on the wings of excessive bad taste—seriously, you have no idea how cleaned up most translations of Lysistrata are— exaggeration, humor and irony.

Enough preamble. Joe Sacco’s Bumf #1, his first fictional work in what feels like forever, is the most necessary comic of 2014. A nightmare that pulls from his roots in underground comix and the work of contemporaries like Michael DeForge and Jim Woodring, Bumf #1 is grappling with American hegemony in a way that serves as a stark reminder of the freedom and possibility that comics allows.

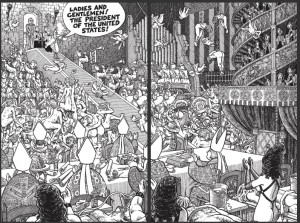

It’s also, to put it mildly, unsubtle. The first two-page spread in the book features Bumf’s narrator telling us that after the Garden of Eden, “There’s been a serious fuck-up,” while surrounded by prostitutes, a woman smacking her child, a man having his brains blown out, a homeless man sitting in front of a garbage can with a human leg sticking out of it, a man hanging himself and the twin towers being hit by planes. Then we’re off to World War II to firebomb some Jerrys and WWI to stroll naked through the trenches while millions of young men die, before seguing into a present day White House where President Barack Obama (drawn as Richard Nixon) attends a meeting in a situation room like something out of Hieronymous Bosch:

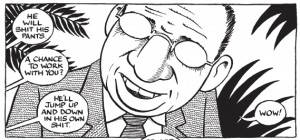

Fiction, then, isn’t Bumf’s only departure from Sacco’s previous major works (the brilliant Footntoes in Gaza, Palestine and Safe Area Gorazde). In leaving the world of comics journalism, he’s also left behind realism entirely. Bumf #1 is a nightmare peopled by a set of symbolic characters pulled from the collective unconscious. First, there’s our narrator, a scummy, chain-smoking, foul-mouthed, bestubbled human face on the body of tweety-bird. Then there’s Colonel Singo-Jingo, fat, British, and monocled, standing up for the old-fashioned values that the 37 million deaths in World War I couldn’t shake. There’s our eventual protagonist, Nixon/Obama. General Custer makes a cameo appearance. Finally, there’s Joe Sacco himself, hired to be the official propagandist of American Empire, composing a story that’s “boy meets girl meets the State.”

These various threads cohere as the United States opens a new “black site” in the form of a portal to a planet in the Andromeda Galaxy, where neither the rules of physics, the ten commandments, nor the Geneva conventions apply:

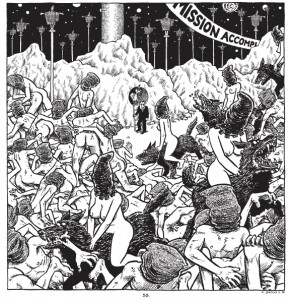

Once in Andromeda, everyone dons hoods, water-boards a few detainees, gets their kicks through drone warfare, and falls in some form of love. The nightmare becomes inescapable, the “black site” an infinite hellscape filled with demon jackals, unsuitable for human life. It is what the novelist and critic Charles Baxter has called a “wonderland,” a place where the character’s fugitive subjectivity has been made manifest in the world surrounding them. Or, as Baxter describes the wonderlands of HP Lovecraft, the environments become “inhospitable interiors, either simple or elaborate, [that] feel like private prisons disturbed by lunatic geometry. Their spaces present vistas of grief-stricken vastness, combined with a steadfast inanimate hostility to any human endeavor. They cannot be a home to anybody. Any effort at domesticity within them would be laughable. No one would want to be there.”

Yet, Sacco points out again and again, we do want to be there. He’s first recruited to join the war effort on the edges of a giant Jacuzzi. Gazing upon it, he remarks, “Wow. The press room sure has changed since I was last here. … this Jacuzzi of yours is serious business.”

“It’s not my Jacuzzi,” the chain-smoking tweety bird replies. “Think of it as the people’s Jacuzzi. Getting in?”

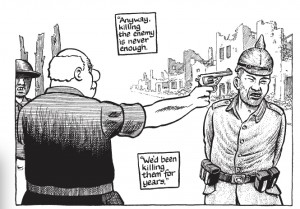

Complicity, in other words, is part of what Sacco’s after here. Bumf #1 essays our collective loss of humanity through the prosecution of an endless war against a series of ever-changing Kaisers stretching back to WWI. In one panel, Sacco recreates the infamous “Saigon Execution” photo, adding a WWI-era German helmet to Nguyen Van Lem’s head. “Killing the enemy is never enough,” Colonel Singo-Jingo intones, “We’d been killing them for years.” (His solution to this problem is rape, by the way, which is never quite shown in Bumf’s one act of tasteful restraint).

This complicity is vast and all encompassing in Bumf. Religion, art, the legal system, love, all are powerless to resist the temptation of power and obedience. What sets Bumf #1 apart from other dystopian nightmares that the characters all want to be there. Whereas other dystopian narratives often revolve around either an epiphanic moment (Brazil) or an already existing discontent that finally finds a venue (The Hunger Games), in Bumf #1, the various characters discover an acceptance of their dehumanized, alien world. A torture victim falls in love with her torturer after he enrolls her in a sensible mobile plan. Sacco comes to enjoy the power and prestige of being the official State Graphic Novelist. Nixon/Obama realizes he’s the Messiah. Gradually, torturer and tortured alike don hoods and lose their clothes. By the final few panels, they are an anonymous collective mass of victor and victim, Sacco’s glasses the only distinguishing feature amidst the hairy bellies and sagging breasts. There’s no hope for us at any point in Bumf #1, which is part of why its humor is so savage, and, while it often adopts the structure of the short gag comic, the jokes are likely to stick in your throat. There’s no escape from the bed we’ve made. All that remains is to lie in it. Getting in?