[Images read from right to left. Wikipedia synopsis of Osamu Tezuka’s Princess Knight (1953) here. It’s a fairy tale romance for kids folks!]

* * *

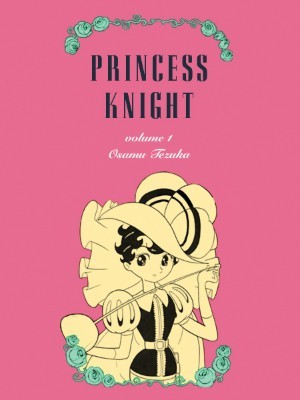

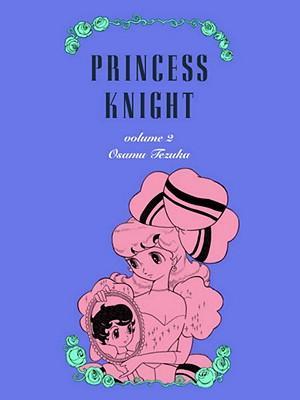

In the cloud strewn halls of heaven, the sexual fate of a group of cherubic “souls” are decided through a lottery of colored hearts. The consumption of a blue heart produces a boy child while the consumption of a red heart produces a girl. When the nascent Princess Sapphire is accidentally fed hearts of two different colors, her sexual fate is thrown into doubt (the covers to the Vertical edition of Princess Knight cleverly highlight this dichotomy). In order to rectify this disastrous turn of events, the supreme deity dictates that her blue heart must be extracted if she is in fact born a girl.

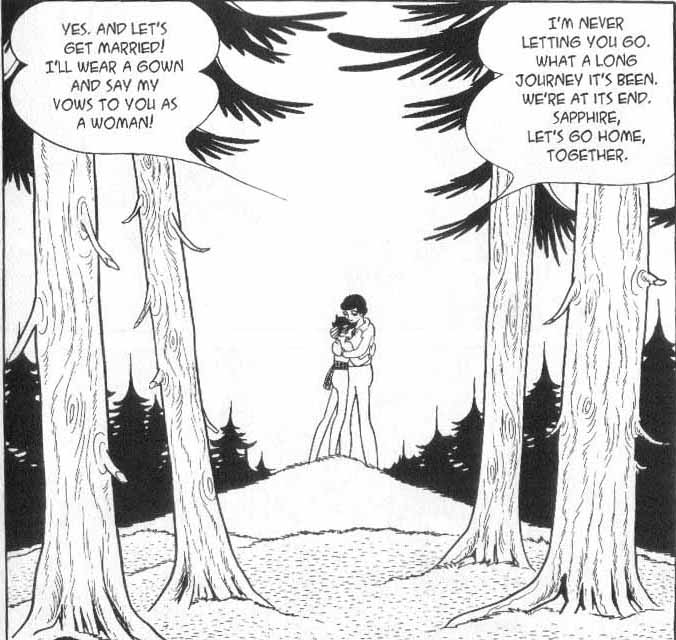

To be sure, this game of hearts has little to do with any real determinacy when it comes to sexual orientation or desire. Rather it is a foreboding of the future course of Sapphire’s life, a premonition of years of chaste crossdressing. The heavenly mix-up is not a recipe for hermaphroditism but for an individual fully at ease in the world of masculine (sword fighting, horse riding, wall climbing) and feminine (pretty dresses, fixations on princes, cat fights) activities.

When Sapphire is born a girl, she remains comfortable with and desirous of her femininity. It is her political circumstances which dictate her need to adopt masculine ways and this she does with a degree of reluctance but with utmost decorum. Her sexual orientation is never in question. As with much children’s literature, this is a world where secondary sexual characteristics like breasts are clearly on display but genitalia never spoken of. Sapphire’s enemies are unable to discover her true sex because she doesn’t have a vagina (nor do Tezuka’s men have penises for that matter) — this constraint undoubtedly due to the age of Tezuka’s readership but also accidentally suggesting that sexual divisions are a cultural product and not predicated on sex organs (hormones not withstanding).

Sapphire is forced to be a prince in public due to the careless birth announcement of a lisping doctor. The swift rectification of this mistake is impossible due to an arcane law which, like most fairy tale legislation, doesn’t hold up to much scrutiny.

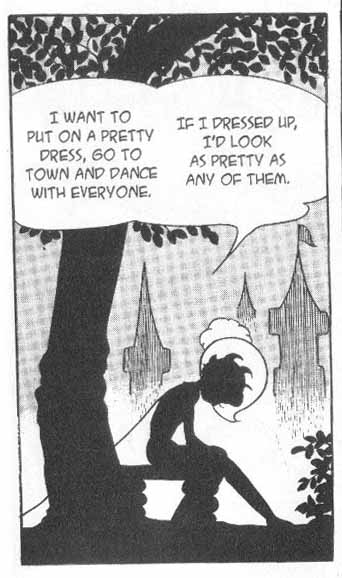

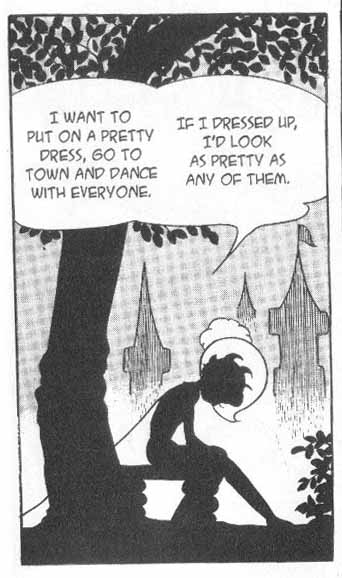

When we first see Sapphire as a young girl, we are swiftly apprised that she likes frilly things. Her transformation into a “prince” is a terrible inconvenience which she has come to accept over the years; an act of subterfuge which has caused such youthful bewilderment that she sometimes forgets to discard her heels in favor of more princely boots.

She is otherwise the consummate professional. Her mastery of disguise beggars that of Clark Kent and Diana Prince with their obfuscating spectacles and boring business suits. Her prince charming is blind to the wiles of his “flaxen” beauty the moment she discards her blonde wig and billowy ball gown. It’s either that or the magic of make-up, you never can tell.

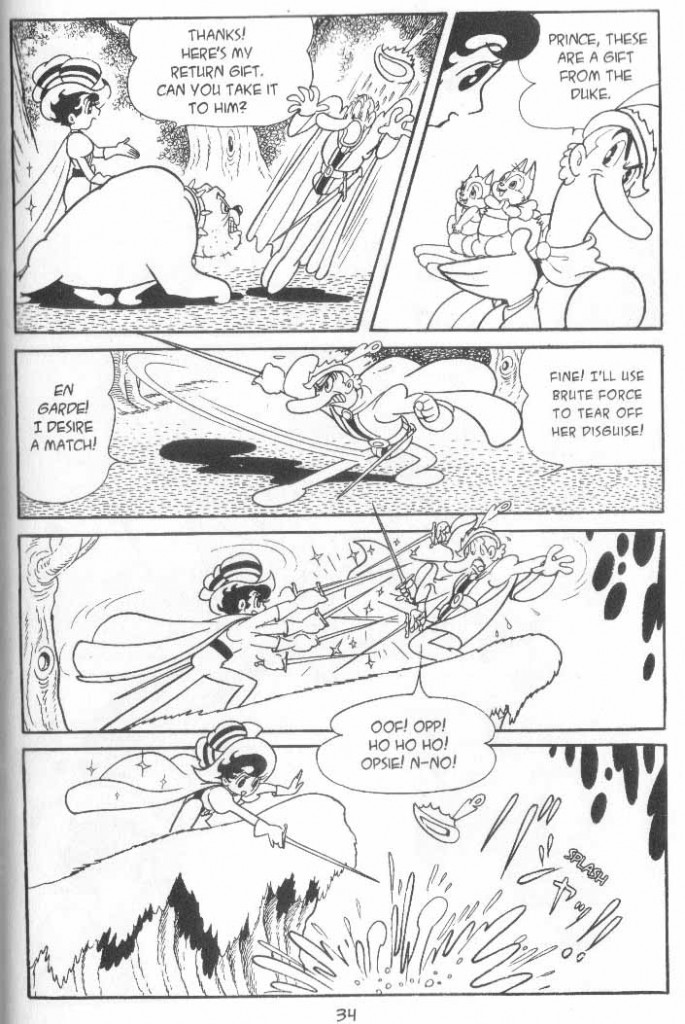

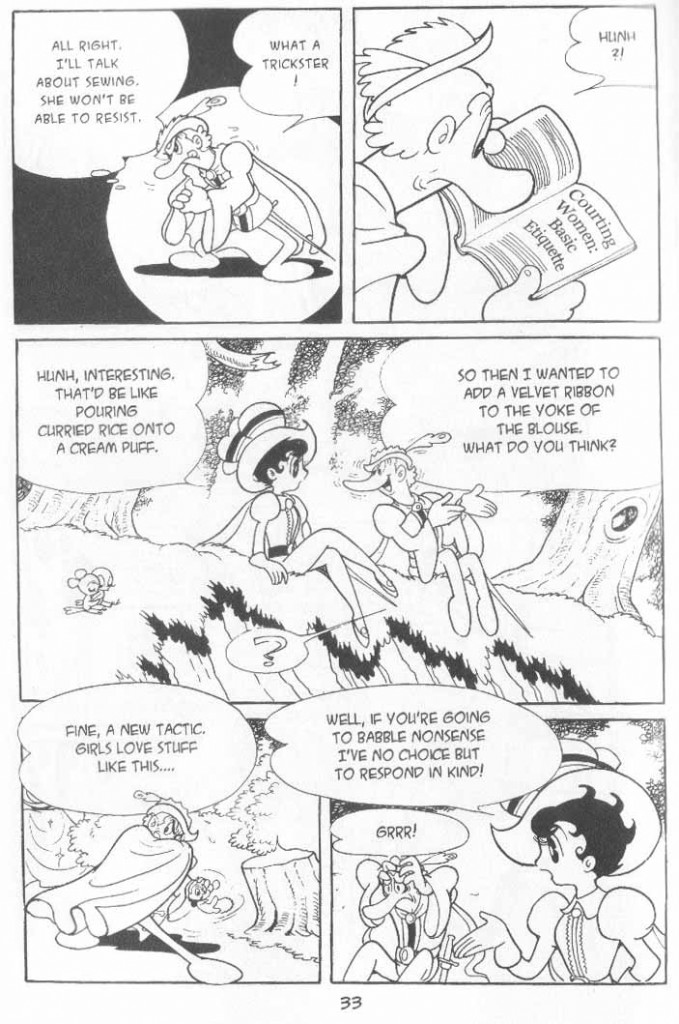

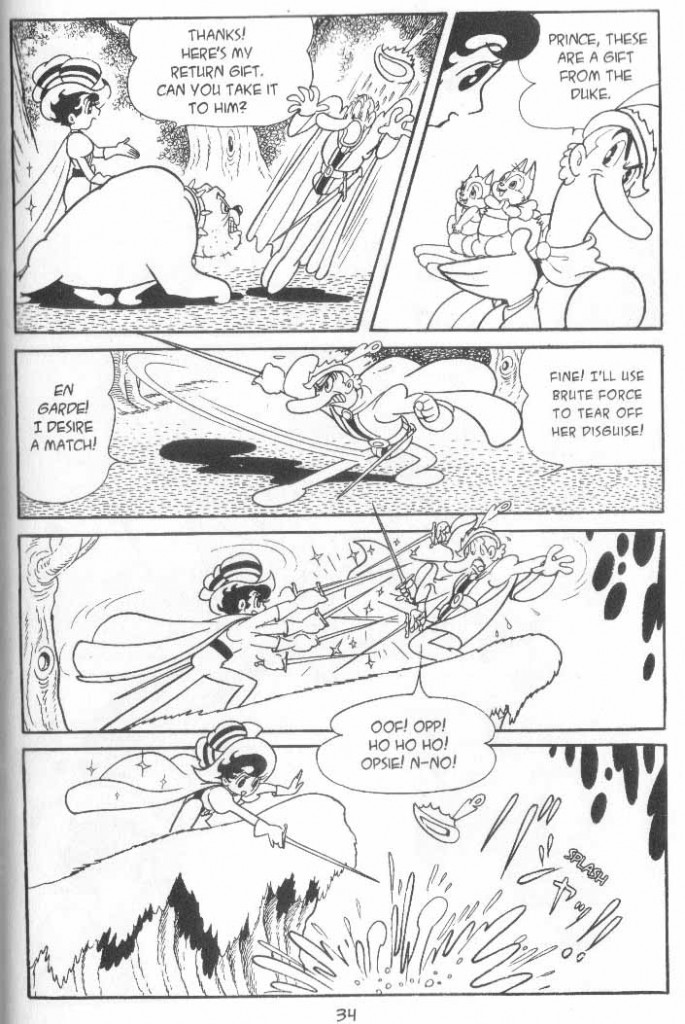

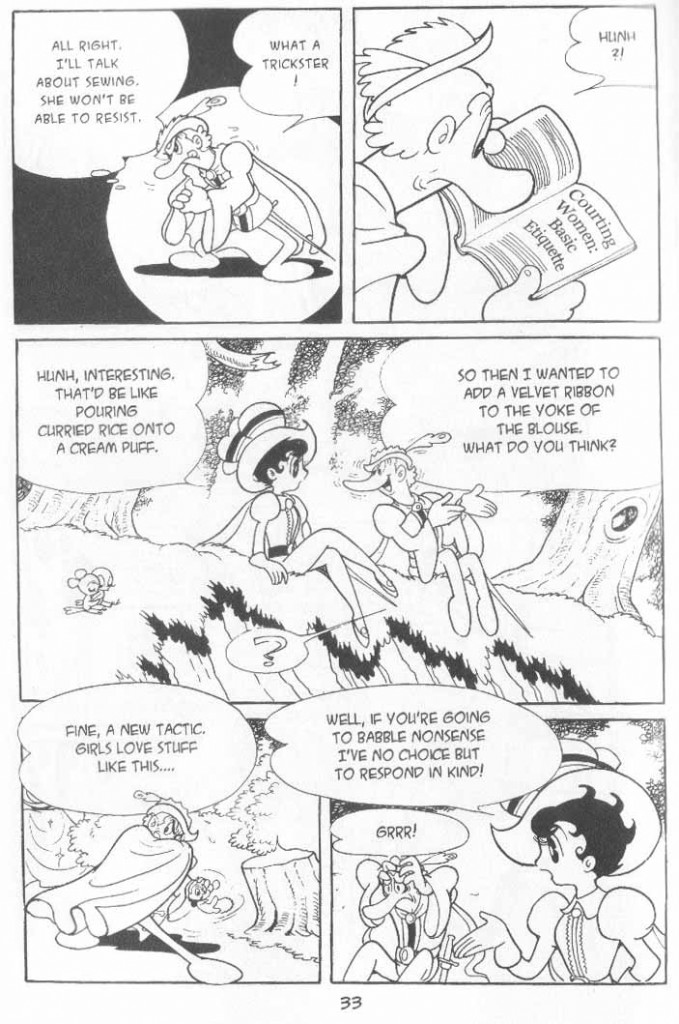

Early on in the story, Sapphire reacts violently to a series of entrapments by a deceitful courtier who attempts to expose her femininity through a woman’s “natural” passions for sewing and cuddly animals.

Yet it is the feminine calling of a beautiful gown that she secretly yearns for.

In many ways, Tezuka is less interested in gender identity (as a crossdressing protagonist would seem to imply) than in a kind of old school female empowerment. Unlike other fairy tale princesses, Sapphire drops a knife and not glass slippers. She is always “correctly” and heterosexually attracted to her prince charming and the aforementioned lavish dresses, yet fully capable of defeating her opponents in single combat — an antediluvian Lara Croft without the pneumatic breasts. The 6th century Ballad of Mu Lan had similar concerns but less reservations about the strength of women.

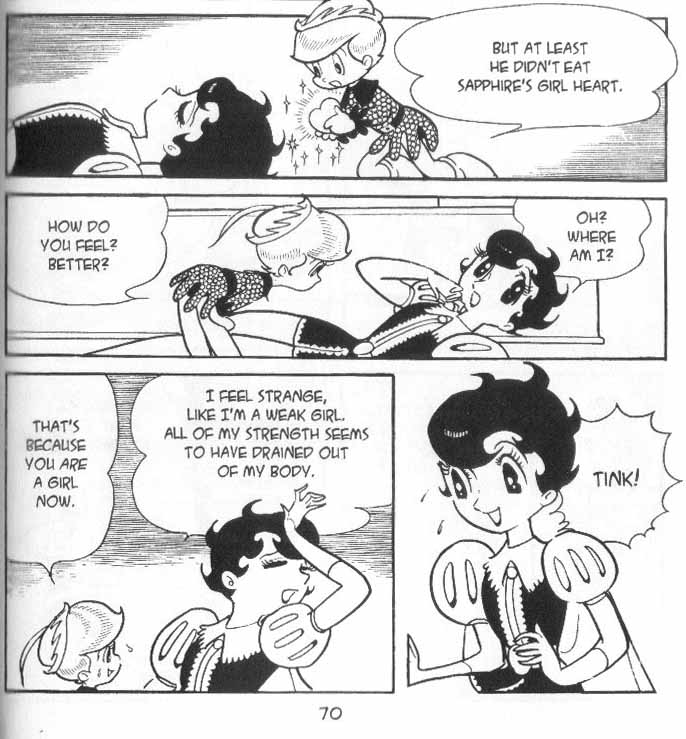

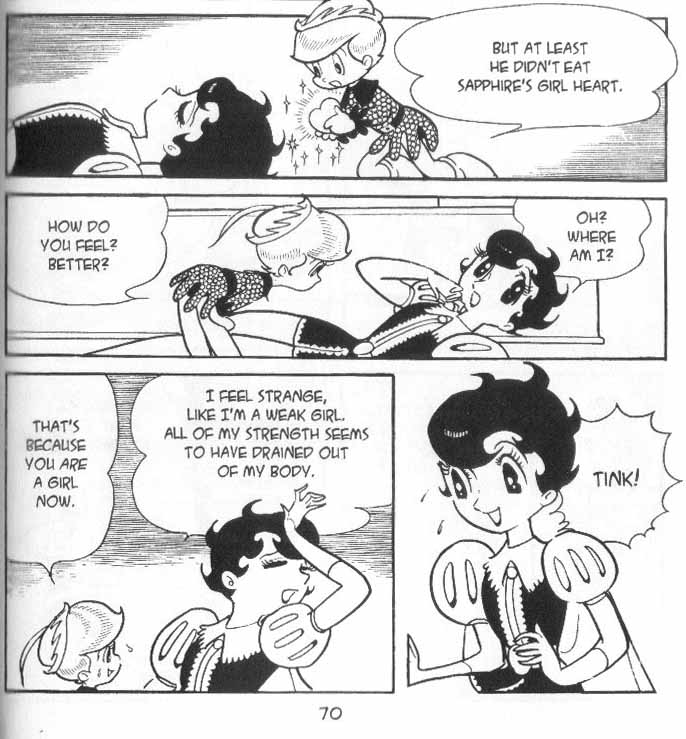

It is only in the second volume of this new translation that Tezuka begins let his guard down. When Sapphire’s female heart is extracted by the nefarious Madame Hell, she struts around in male fashion and rejects the advances of her prince lover. A more conservative approach is adopted when her angel guardian reverses this magical surgery and replaces her male heart with a female one — she becomes a wilting flower…

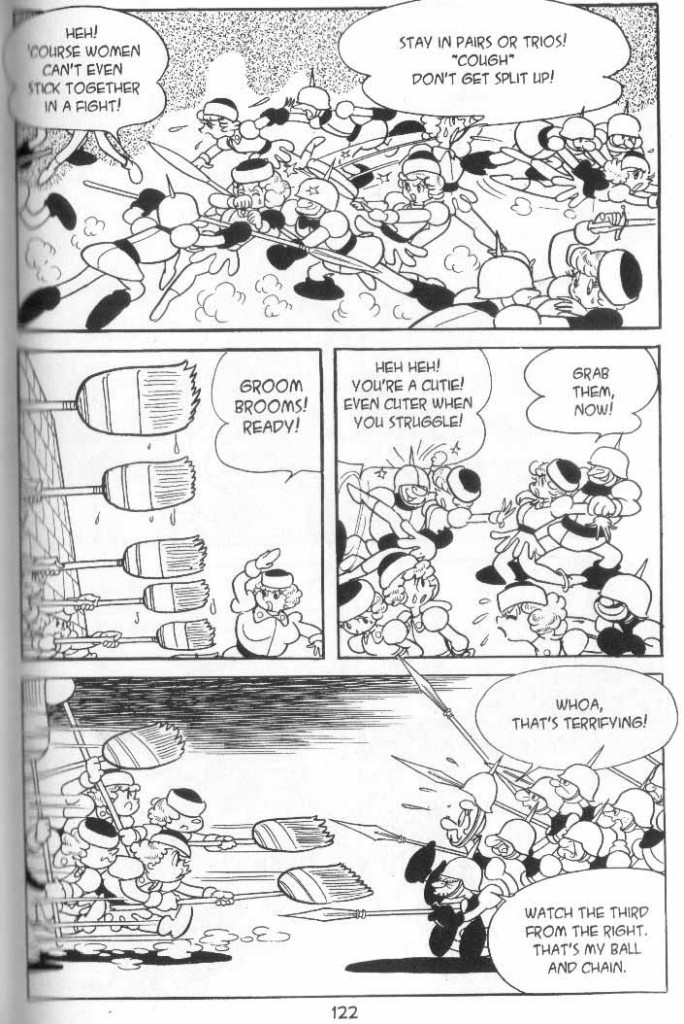

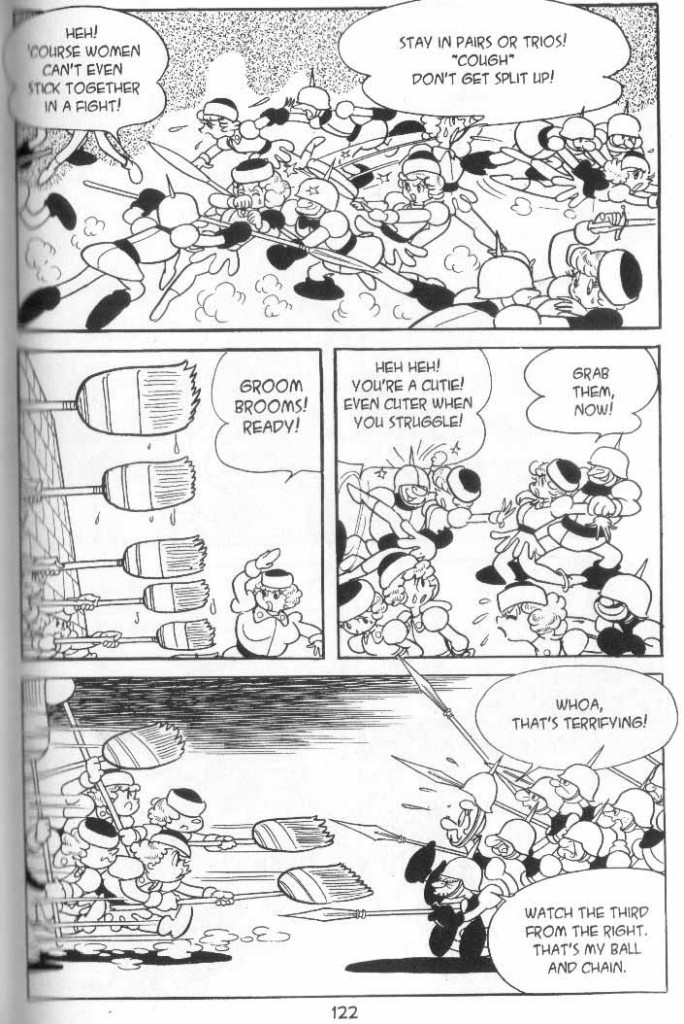

….a stance Tezuka swiftly dispenses with in light of his mildly feminist agenda. What’s an adventuring heroine to do if she can’t wield a sword? Even the emancipated ladies of the court use brooms to engage some invading soldiers.

Despite its long standing tradition of being the castrato of the comics world, North American comics have had an endless fascination with the transgendered lifestyle. Many of these are almost monkishly respectful while others posit rape as the first instinct of a male-female body swap (see Skin Tight Orbit; an erotic fantasy written by Elaine Lee). The latter device is a common trope in transgendered pornographic fiction.

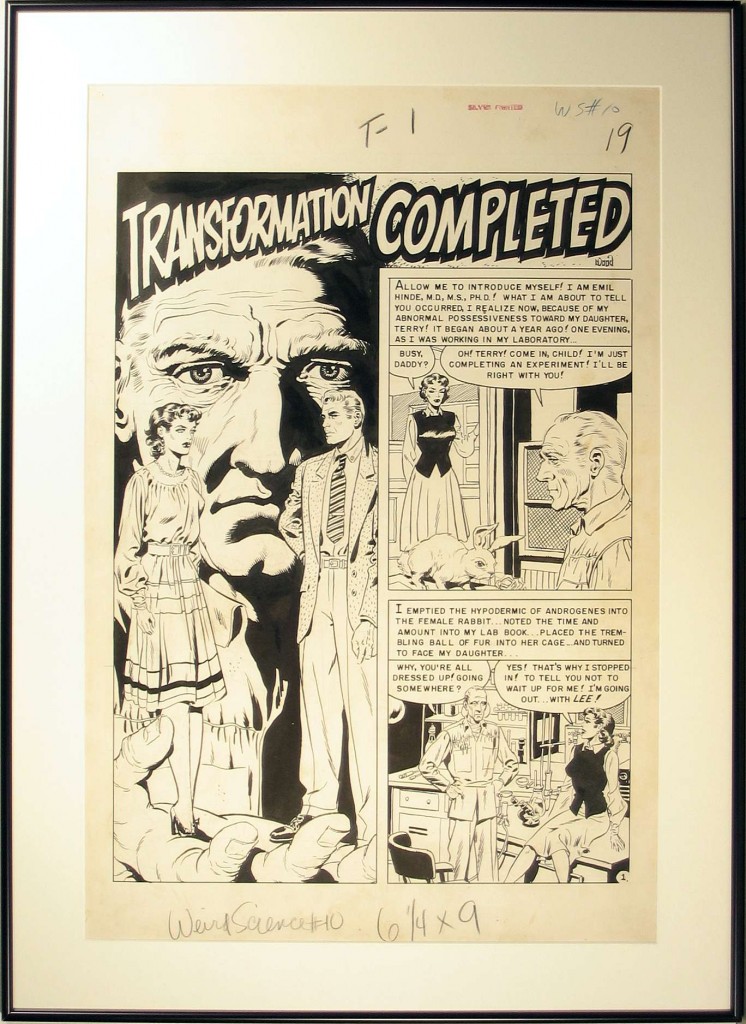

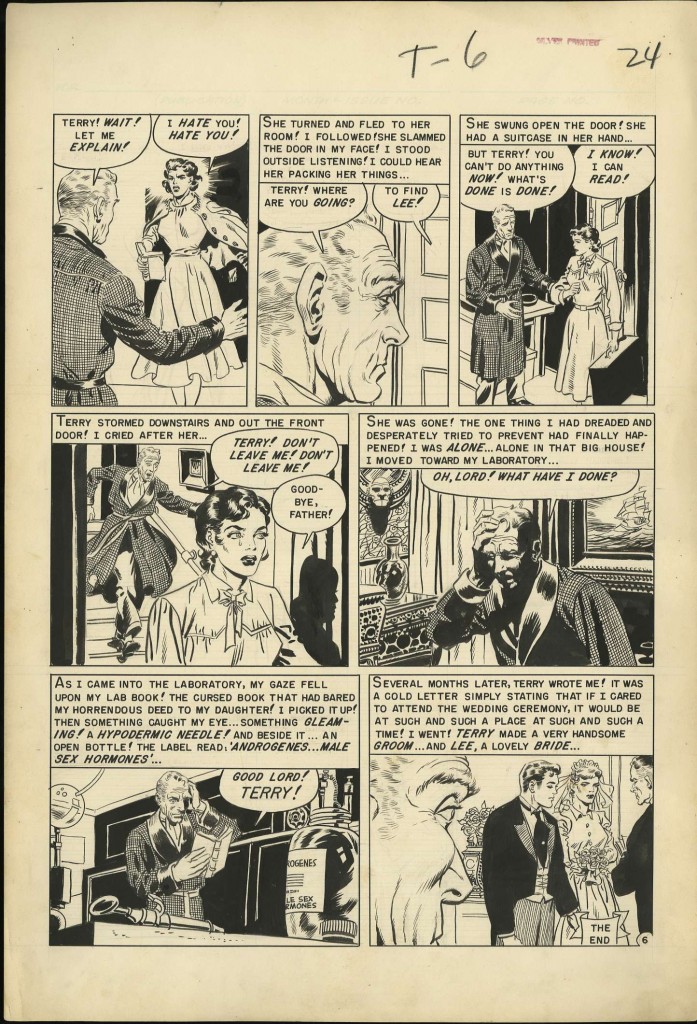

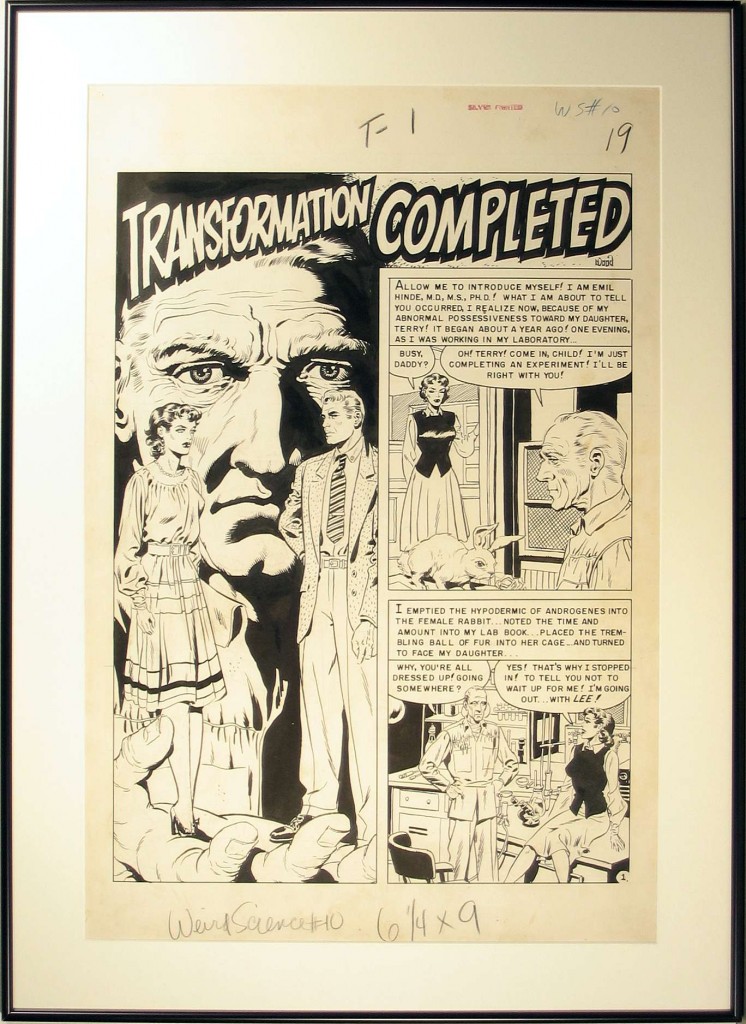

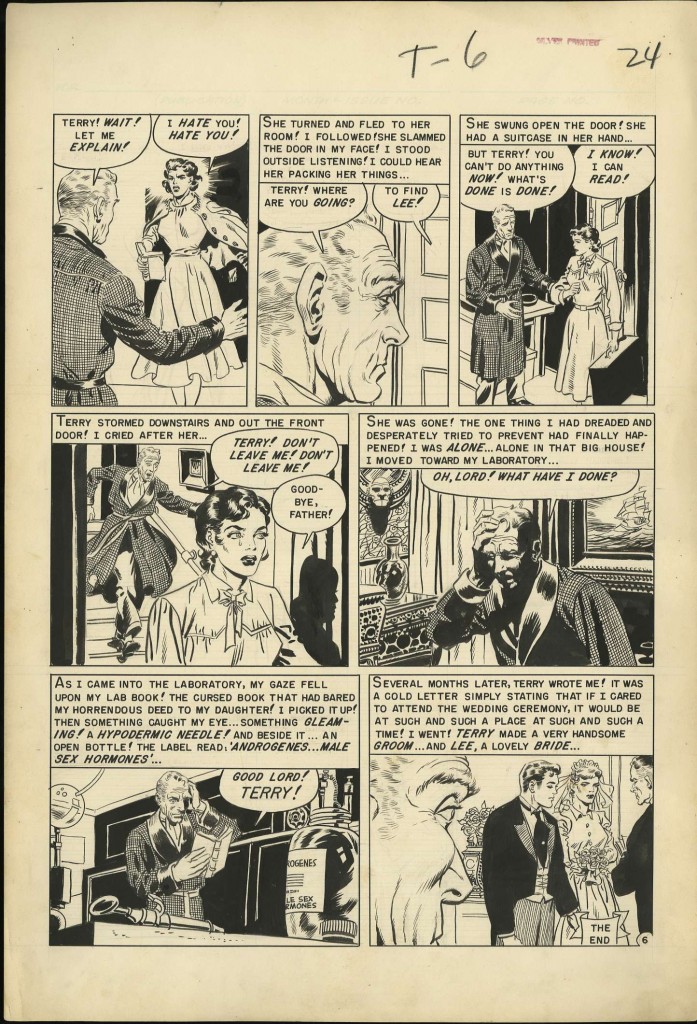

The transgendered stories surrounding Superman are perhaps the most entertaining from a historical perspective, but the canonical text in the genre must be Al Feldstein and Wally Wood’s “Transformation Completed” (Weird Science #10, 1951).

Here the unwitting fiancé of the female protagonist (androgynously named Terry) is transformed into a woman by her jealous father. Two constraints are at work here. Firstly, the bugbear of the homosexual lifestyle which can never be in a children’s comic and, secondly, the EC line’s own penchant for the “shock” ending. Both of these factors ensure that mere lesbianism will never be an option as far as the couple’s fortunes are concerned. On the final page of the story, Terry injects herself with her father’s gender change drug and becomes the groom to her newly female bride.

This kind of slow, forced feminization and simple gender reversal is a mainstay of transgendered literature (pornographic or otherwise), and satisfies both male-to-female and female-to-male desires and fantasies. We can see something similar at work in the operative female perfection achieved in Almodovar’s forced feminization horror-fantasy film, The Skin I Live In. Here the possibility of a lesbian romance is held up as the final shred of hope after years of sexual abuse at the hands of Antonio Banderas’ surgeon-torturer.

Needless to say, Tezuka will have no truck with any of this. The manga is question is for kids afterall. The taboo of abandoning the straight and narrow of the female lifestyle is suggested by no less than a minion of Satan (Madame Hell) and is rejected outright. [Sidenote: the female reincarnation of Tristan in Barr and Bolland’s Camelot 3000 is offered a similar bargain by Morgan le Fay but finally opts for lesbian love with her Isolde]

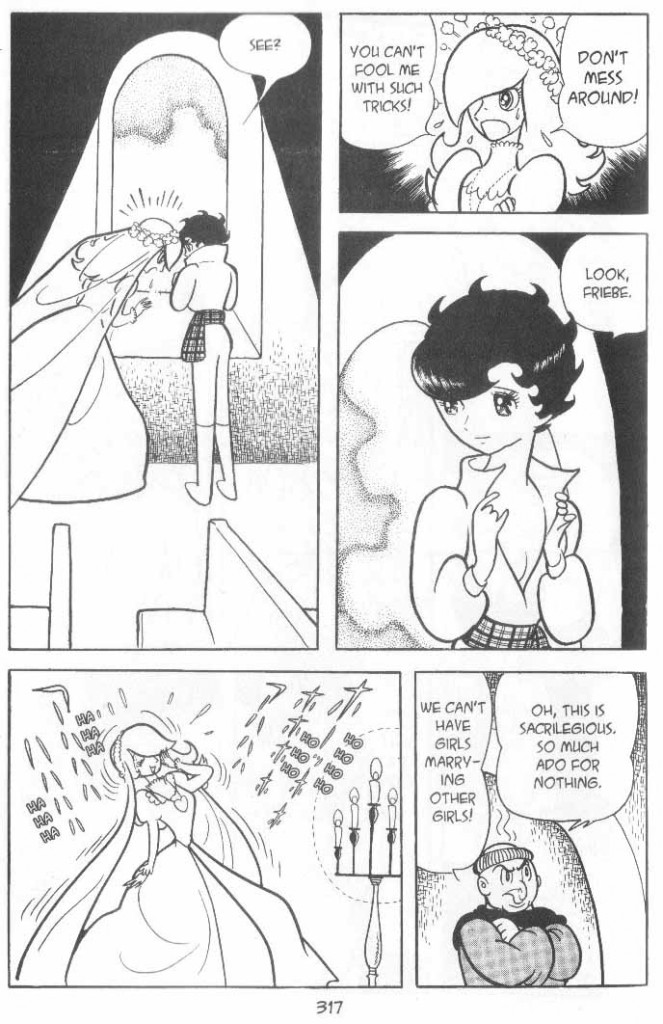

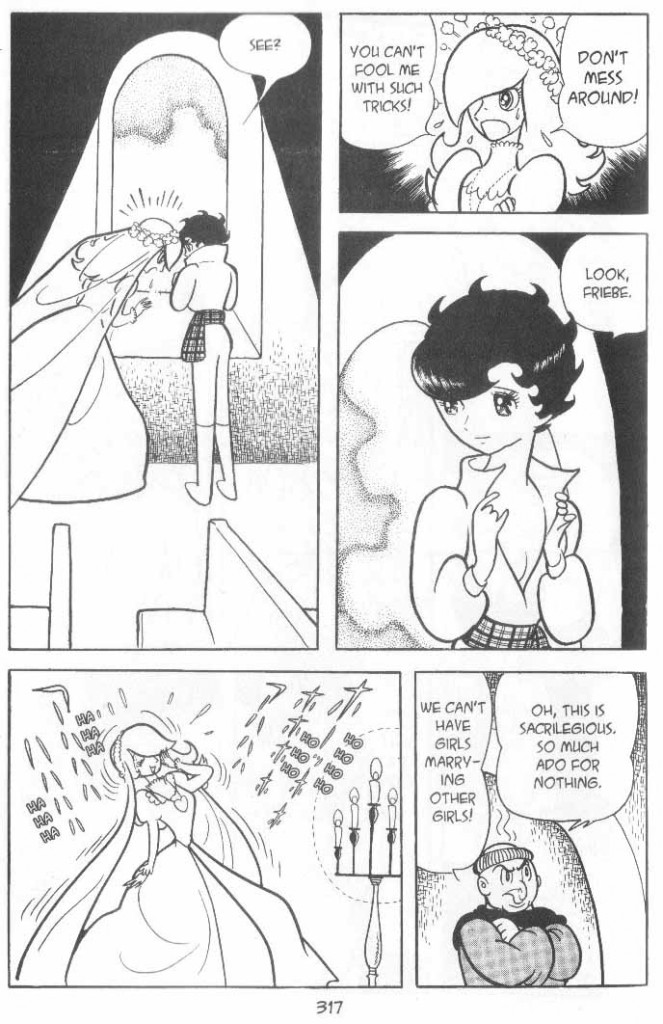

Readers prone to detect the lesbian frisson in the performances of the Takarazuka revue (said to be an influence on Princess Knight) will be left bereft by the heterosexual mores and desires of the protagonists in the manga. Sapphire’s potential bride (as seen in the penultimate chapter of the series) is left weeping at the altar once she is apprised of her groom’s substantial bosom; a Shakespearian moment further emphasized by the translator’s choice of priestly complaint (“Oh, this is sacrilegious, so much ado for nothing.”)

Considering its worthy progenitors in the field of literary transvestism, one might say that the most surprising aspect of Princess Knight is not its crossdressing heroine but the author’s need to contrive a celestial accident for a woman to be skilled at athletic and martial activities. What little “feminism” we see on the page soon gives way to escapades not dissimilar to what you might find in the adventures of Zorro, The Prisoner of Zenda, or a movie starring Douglas Fairbanks. One assumes that this presents an advance over the usual position of women in comics during the 50s and is to be commended.

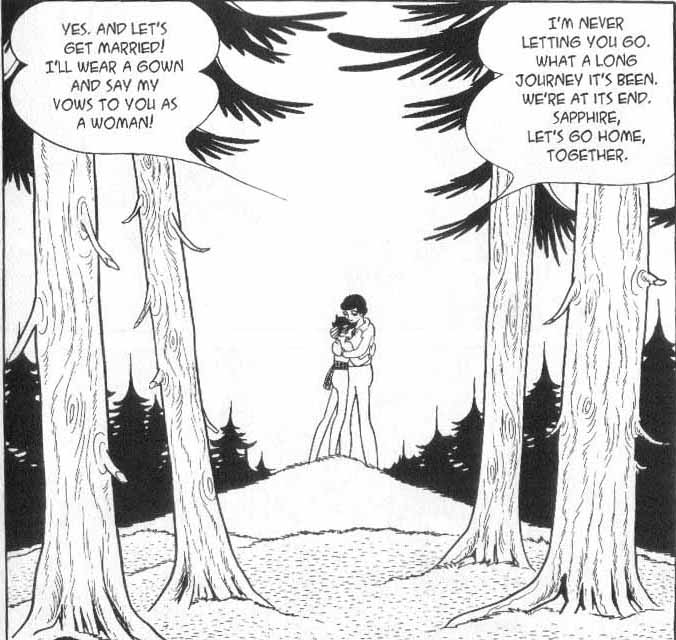

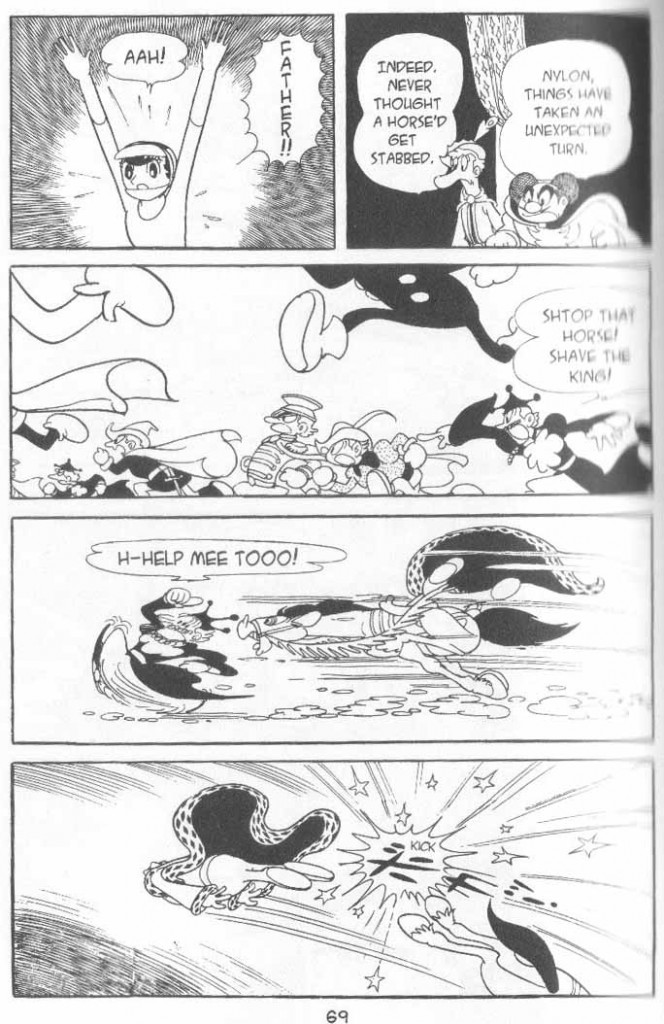

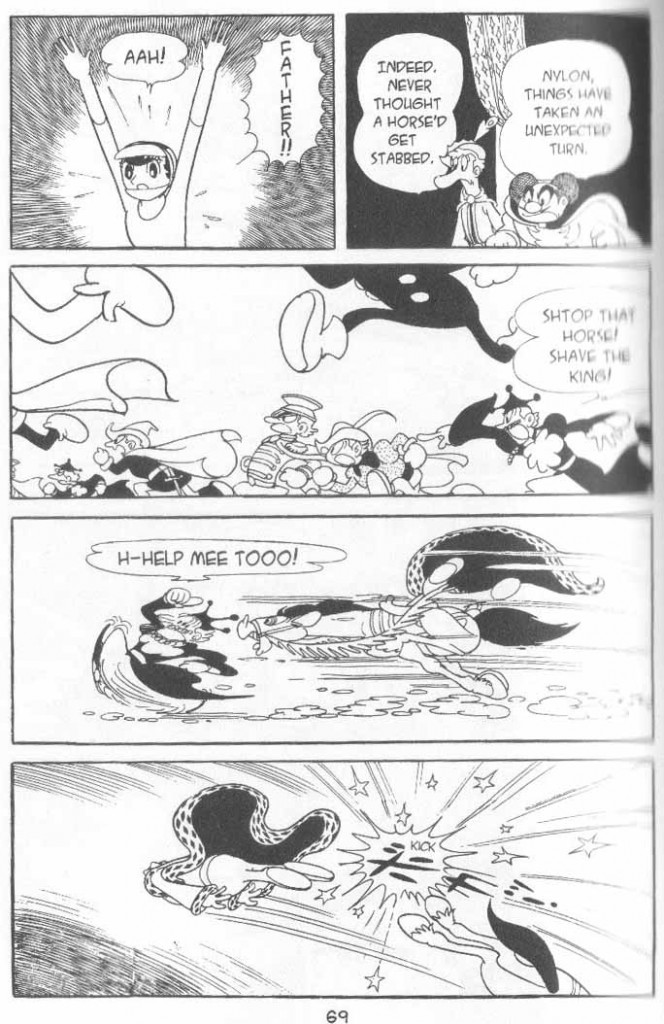

Nevertheless, this is a manga to be read more out of a sense of duty than anything else. Its historical importance as far as manga directed at girls is concerned is indisputable, but the romantic dilemmas on show are uninvolving. The tiresome and largely unimaginative plots will prove a chore for most. It is undoubtedly virtuous in intention but also averse to do away with childish things even if only for a moment — a product of its time with all the limitations that implies. Nowhere is this more clearly seen than in the death of Sapphire’s father which is not so much a terrible moment (see Bambi or Charlotte’s Web) but a simple plot development and an exercise in frantic cartooning.

There can be little doubt that Princess Knight remains a perfect example of that safe, asexual entertainment people have come to expect from comics.