This was first published at Splice Today. I thought I’d reprint it since it touches on some issues raised in this comments thread.

____________________________

Usually we think of empathy as a generous emotion; a gift of love. Just as often, though, it can be a crabbed, demanding, jealous thing — an insistence that others act like, think like, and even be oneself.

Usually we think of empathy as a generous emotion; a gift of love. Just as often, though, it can be a crabbed, demanding, jealous thing — an insistence that others act like, think like, and even be oneself.

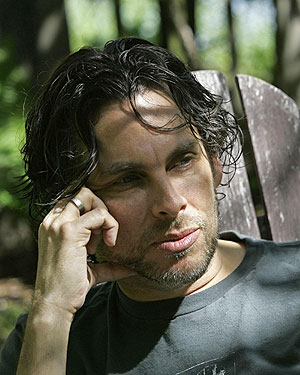

Michael Chabon is a writer of literary fiction, which means that in many ways, even more than a politician, he is a professional empathizer. Last week he was plying his trade as a guest-blogger for Ta-Nehisi Coates. As a matter of course, he wrote about the Tucson shooting, and specifically about Obama’s speech.

His post on the subject was mostly about the distance he felt from the speech, the audience, and indeed, from the nation. He began the post by declaring, “I’ve been thinking about the president’s speech all night and this morning, how something about it left me feeling left out.” He acknowledges that he was moved by Obama’s vulnerability and his exhortation to live up to the memories of the victims, “And yet…”, he says:

Was it all the weird, inappropriate clapping and cheering? Or the realization that I am so out of touch with the national vibe that I didn’t know that whistling and whooping and standing ovations are, when someone evokes the memory of murdered innocent people, totally cool? I never would have thought that I’d spend so much of that solemn Wednesday thinking—first on publication of Sarah Palin’s latest piece of narrishkeit about the blood libels, then all through the memorial service—please, I beg you, can you not, finally, just shut up? It was distancing. Distracting. As he joined in, at times, with the applause, the president’s hard, measured handclaps, too close to the microphone, drowned out everything else in my kitchen right then, and seemed to be tolling the passing of something else besides human lives. I don’t know what. Maybe just my own sense of connectedness to the cheering people in that giant faraway room. I didn’t feel like applauding right then, not even in celebration of the persistence and continuity of human life and American values. And then I was ashamed of my curmudgeonliness. Those people, after all, many of them college students, were in a sports arena; architecture gives shape to behavior and thought. Maybe if the service had been held in a church, things would have played differently.

Chabon then goes on to sneer (empathetically, thoughtfully) at Obama’s final image in the speech; the moment when he suggested that Christina Taylor-Green, the nine-year-old killed in the shooting, might be jumping in puddles in heaven.

I tried to imagine how I would feel if, having, God forbid, lost my precious daughter, born three months and ten days before Christina Taylor-Green, somebody offered this charming, tidy, corny vignette to me by way of consolation. I mean, come on! There is no heaven, man. The brunt, the ache and the truth of a child’s death is that he or she will never jump in rain puddles again. That joy was taken from her, and along with it ours in the pleasure of all that splashing. Heaven is pure wishfulness, an imaginary solution to the insoluble problem of the contingency and injustice of life.

Chabon concludes by noting that the image was okay after all if you inverted it and saw it as a metaphor for loss.

But I’ve been chewing these words over since last night, and I’ve decided that, in fact, they were appropriate to a memorial for a child, far more appropriate, certainly, than all that rude hallooing. A literal belief in heaven is not required to grasp the power of that corny wish, to feel the way the idea of heaven inverts in order to express all the more plainly everything—wishes, hopes and happiness—that the grieving parents must now put away, along with one slicker and a pair of rain boots.

So. That’s Chabon.

As for me, I spent most of “that solemn Wednesday” without any expectations in particular. As somebody without any connection to any of the victims, I didn’t even experience it as especially solemn. I didn’t watch, and don’t intend to watch, Sarah Palin make a fool of herself, because I know she’s a fool already, and why would I want to be irritated? I’ve enjoyed reading a number of pundits make fun of her, though (this is probably my favorite.)

I didn’t watch the president’s speech on Wednesday, either. In fact, I’ve been more or less avoiding news about the speech and about the people shot, because I find hearing about people getting shot upsetting. Especially young children — not because I’m empathetic or thoughtful, but because, like Chabon, I have a kid (he’s 7) and thinking about him dying makes me feel sick. I skimmed a transcript of the speech a day or so later. And I watched the video today because I was thinking about this article and felt like I had to.

The speech itself — well, it made me cry. I don’t know if that’s a testament to the president’s eloquence particularly. I cry pretty easily, and a bunch of people murdered for no reason is sad.

The cheering didn’t bother me. It’s odd, really, to think of it as an occasion for aesthetic approbation or denigration. People express grief in various ways. It seemed mostly like they were trying to let Obama and each other know that they were a community. Or maybe like Chabon says, they were just brainwashed by the architecture into behaving inappropriately. Whatever. I noticed that Giffords’ husband was clapping. I don’t feel I’m in a place to judge him.

As for rain puddles in heaven; yes, it’s trite. But it seems a little duplicitous to think of that triteness as causing Christina Taylor-Green’s parents more pain. If my son died, it’s not clear to me what anyone could say that would make things any worse or any better. Besides, you spout trite nothings when someone’s loved one dies, because what else do you say? A polished prose style is a lovely thing, but that doesn’t mean it’s an adequate response in all circumstances.

This, indeed, seems to be the cause of part of Chabon’s dyspepsia. Artists, especially successful artists like Chabon. receive such fulsome praises that I think they can occasionally mistake themselves for priests. Which is maybe why he felt qualified to proclaim with such certainty that heaven isn’t real and that death is just absence. To suggest otherwise is a stylistic error — rectifiable only by transforming the clumsy words of the President through the magical gifts of a real writer.

But I’ve been chewing these words over since last night, and I’ve decided that, in fact, they were appropriate to a memorial for a child, far more appropriate, certainly, than all that rude hallooing. A literal belief in heaven is not required to grasp the power of that corny wish, to feel the way the idea of heaven inverts in order to express all the more plainly everything—wishes, hopes and happiness—that the grieving parents must now put away, along with one slicker and a pair of rain boots.

Job’s comforters are a standing reminder that most people will engage in condescending assholery if offered half a chance. No reason that a lauded author should be any different, I guess.

Still, it’s worth analyzing the exact nature of the assholery. Job’s comforters were jerks because they believed that Job was suffering for a reason. His injuries were his fault or they would lead to a greater good. The comforters believed they could read tragedy. They were its interpreters.

Chabon isn’t coming from exactly the same place, but there’s some overlap. He too, believes that the tragedy should speak to him. He is irritated when he is excluded. Why doesn’t the President move me, he asks? Why doesn’t the event address me? Why this talk of heaven when I’m not a believer? Why don’t all these people who I am not interested in — why don’t they all, as he puts it, “shut up”?

The answer to all of these questions, of course, is fairly straightforward. That answer is: “It’s not about you, Michael.” Even your empathy, however well expressed, doesn’t make it about you.

Of course, lots of people who weren’t immeditately affected feel personally connected to the shootings. I do too, to some extent. But it’s important to recognize that that extent is limited. The separation Chabon felt from the people in that arena wasn’t because the people in Tucson are gauche, or because Obama is a Christian. If those things matter at all, it’s only as symbols of the way in which each person is different; a mystery, one to another. Art and love and religion bridge the distance partially and sometimes, but not entirely, and not on demand. God perhaps can love and know each individual, but for a human to try to do so starts to look like blasphemy. Even if, or perhaps especially if, you don’t believe that God exists.