This was one of those pieces where I said to myself as I was writing it, “I can’t believe a mainstream magazine is going to print this! That’s so cool!”

And as ever when I say that to myself, the editor who had accepted the pitch looked at it and didn’t get it. So, I thought I’d run it here for my patrons. This is my third Twisted Mass of Heterotopia column; if you like it, please consider donating to my Patreon so I can write more pieces like this.

______________________

Fan fiction is despised. Criticism is despised. And both are despised for the same broad reason; they’re seen as parasitic. If a critic was a real artist, the critic would make a film rather than just writing about how superhero films are crap. If a fan fiction writer were truly creative, that fan fiction writer would develop their own characters and plots, rather than having Spock pour his heart out to Kirk for the gazillionth time. Great artists are originals; fan fiction writers and critics are derivative copyists, battened, like great aesthetic mosquitoes, upon the blood of their betters.

Fan fiction is despised. Criticism is despised. And both are despised for the same broad reason; they’re seen as parasitic. If a critic was a real artist, the critic would make a film rather than just writing about how superhero films are crap. If a fan fiction writer were truly creative, that fan fiction writer would develop their own characters and plots, rather than having Spock pour his heart out to Kirk for the gazillionth time. Great artists are originals; fan fiction writers and critics are derivative copyists, battened, like great aesthetic mosquitoes, upon the blood of their betters.

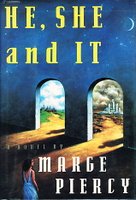

Charlie Lovett’s The Further Adventures of Ebenezer Scrooge must be doubly derivative, then, since it is both fan fiction and literary criticism. Lovett is best known for his best-selling book-centered mystery, The Bookman’s Tale. But in The Further Adventures he moves from broad bibliphilia to individual homage—or individual theft, if you’d prefer.

The short novella picks up twenty years after the end of Dickens’ famous A Christmas Carol. The formerly miserly Scrooge is now as renowned for his manic generosity and good will as he once was for his ill temper. “A generous, charitable, jolly, gleeful, munificent old fool, yielding as a feather pillow that welcomed the weariest soul to its downy breast,” as Lovett describes him in solid faux Dickensian prose. Determined to do even more good, Scrooge calls upon the Christmas spirits to work their nighttime magic on others: his newphew, his former-assistant-now-partner Bob Cratchitt, and his bankers. The result (spoilers!) is additional joy on earth for all.

The story is mostly an excuse to visit with Scrooge again, and for Lovett to splice in various passages from Dickens (the description of the the London slums from Bleak House, for example) with his own pastiche. But while the book is mostly tribute, it also functions as a criticism of the original novel. Early on, it mildly tweaks Dickens’ sentimentalism; Scrooge’s unfailing good cheer is, it turns out, as irritating as his former dyspepsia. Over twenty years, in fact, Scrooge’s “constant kindnesses had grown wearisome from years of use.” Is Scrooge generous, or is he, in his single-minded effort to store up treasures in heaven, really as selfish and unconcerned with others as he was in his single-minded miserliness? Maybe the ghosts didn’t change him all that much after all.

The main critique though, comes in the second half of the novella, when the ghosts lead Scrooge’s nephew to run for Parliament, and inspire his bankers to set up a permanent charity. Dickens’ Christmas Carol presents personal transformation as the route to social good; God reaches down and makes the world a better place by changing Scrooge’s heart. Lovett, though, suggests that ghost Marley’s chains can never really be taken from him through individual acts of kindness. Real change, and really helping people, requires political power and institutional investment.

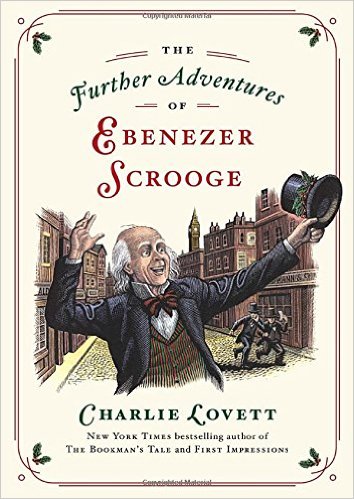

Lovett’s combination of fan fiction and criticism isn’t an aberration. On the contrary, literary fan fiction like The Further Adventures of Ebenezer Scrooge frequently includes, or is based upon, a critical reading of the original work. Jo Baker’s marvelous Longbourn (2013), for instance, is a reworking of Pride and Prejudice from the point of view of the servants. As such, it functions as a counter-intuitive, but powerful reading of the original novel. Suddenly, the Bennett household is built, not on the goodness and wisdom of Jane and Elizabeth, but on the raw hands and constant toil of the women below stairs who wash the sheets and make the dinner. And Elizabeth’s story is not so much about true love, as it is about the power and privilege which enable true love. “What it is to be young and lovely and very well aware of it,” the servant Mrs. Hill thinks while looking at Elizabeth. “What it is to know that you will only settle for the keenest love, the most perfect match.” Mrs. Hill could not settle for the perfect match; she fell in love with Mr. Bennett, had his child, then had to give the boy (Elizabeth’s half brother) away to avoid scandal. Austen’s vision of respectable, respectful love is only possible because she’s in a family, and a class, where they can afford respectable, respectful love. Other people aren’t so lucky.

Again, criticism is often seen as parasitic on original art. But in Longbourn, this is turned around. Jo Baker’s novel is essentially parasitic on critical insight. The kernel of the novel is the critical question, how is class erased in Pride and Prejudice? “The main characters in Longbourn are ghostly presences in Pride and Prejudice, they exist to serve the family and the story,” Baker says in an author’s note. “But they are—at least in my head—people too.” The commentary on, and critical reading, of Pride and Prejudice becomes a work of art of its own.

Jo Baker isn’t the only writer who builds her art on criticism. Jane Austen, famously, did the same in Northanger Abbey, a book which is a parody, or reworking, of the Gothic novels of Austen’s day. Just as Lovett questions the presuppositions of Dickens, and Baker questions the presuppositions of Austen, so Austen’s novel is an extended critique of the tropes of the Gothic. “No one who had ever seen Catherine Morland in her infancy would have supposed her born to be an heroine,” is Austen’s opening line—pointing not forward into the story, but backwards towards all those other Gothic narratives with extraordinary heroines. “She had a thin awkward figure, a sallow skin without colour, dark lank hair, and strong features—so much for her person; and not less unpropitious for heroism seemed her mind. She was fond of all boy’s plays, and greatly preferred cricket not merely to dolls, but to the more heroic enjoyments of infancy, nursing a dormouse, feeding a canary-bird, or watering a rose-bush.” Austen is criticizing, and questioning those perfect, feminine, marked-for-destiny Gothic heroines, just as Baker criticized and questioned Austen’s own sprightly, self-confident, self-determining ones. If Baker is parasitic on Austen, then Austen is parasitic on those Gothic novels — or, more directly, on a critical analysis of those Gothic novels. If Baker is Austen fan-fic, why isn’t Austen Gothic fan-fic?

Dickens’ Christmas Carol is not a direct parody or reworking of another story. But still, Lovett’s fan fiction seems so much in the spirit of the original in part because A Christmas Carol functions in a lot of ways as a criticism, or fan fiction retelling, of itself. Scrooge starts out as a “tight-fisted hand at the grindstone…a squeezing, wreching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous, old sinner!” That’s the iconic Scrooge…and then the rest of the book shows us what’s left out of the portrait, just as Jo Baker shows us what’s left out of Austen, and Austen shows us what’s left out of the Gothic. The ghosts don’t just transform Scrooge; they transform that original vision of Scrooge. We see his childhood; his love for his sister; his fiancé; we see, in other words, that the hard-hearted, miser Scrooge is not the whole story. Dickens could be seen as writing his own fan-fiction, creating an Elseworlds version of his own character. What if Superman had landed in Russia? What if Scully and Mulder had a passionate fling? What if Scrooge were a good man? That last is the premise of The Further Adventures of Ebenezer Scrooge — but it’s also the premise of A Christmas Carol.

Criticism, fan fiction, and original art seem like easily separable categories; Mark Twain’s works goes in the library, your online Twilight story about Edward and Jacob and all the things they do goes in the online forum, this essay you’re reading right here is in the TNR books section. But Mark Twain wrote Arthurian fan fic (and criticism) in Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. E.L. James’ Twilight fan fic went to the best-sellers list. This essay is, admittedly, not likely to enter the western canon, but still, I contend that it’s inspired by the same impulse as Baker’s Longbourn, or Northanger Abbey or those further adventures of Ebenezer Scrooge. For art, for criticism, or for fan fiction, the question is always the same. How might this story be changed? Questioning the world, playing with the world, and creating the world — those things aren’t so different. We can maybe even write a story, or an essay, if we’d like, and imagine a place, much like this one, where they’re all the same.