The index to the Indie Comics vs. Context roundtable is here.

____________

“Ridicule or attack on any religious or racial group is never permissible.” – From General Standards Part C of the 1954 Code of the Comics Magazine Association of America

One of the consequences of the CMAA “Comics Code” of 1954 was that industry artists, writers, publishers, and distributors stopped taking risks when it came to race. At least, for a while. The slippery language of the “religion” section of General Standards Part C was broad enough that even the most tentative efforts to find an audience for increasingly complex, multi-dimensional images of blackness were scaled back. For several years, as the Civil Rights Movement transformed the social and political landscape of America, the mainstream comic book industry erred on the side of caution. (And I’m not just talking about those infamous beads of sweat.)

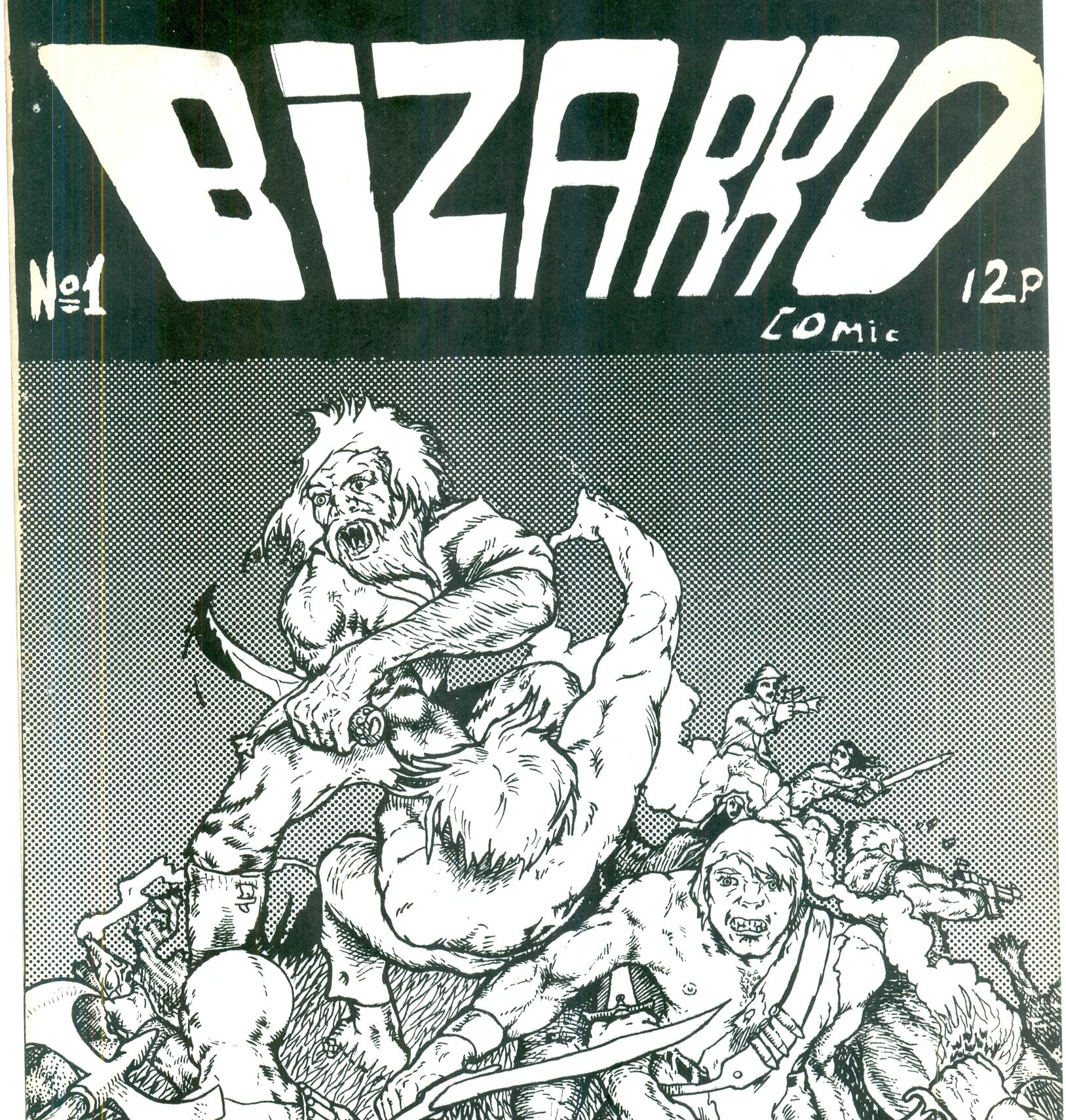

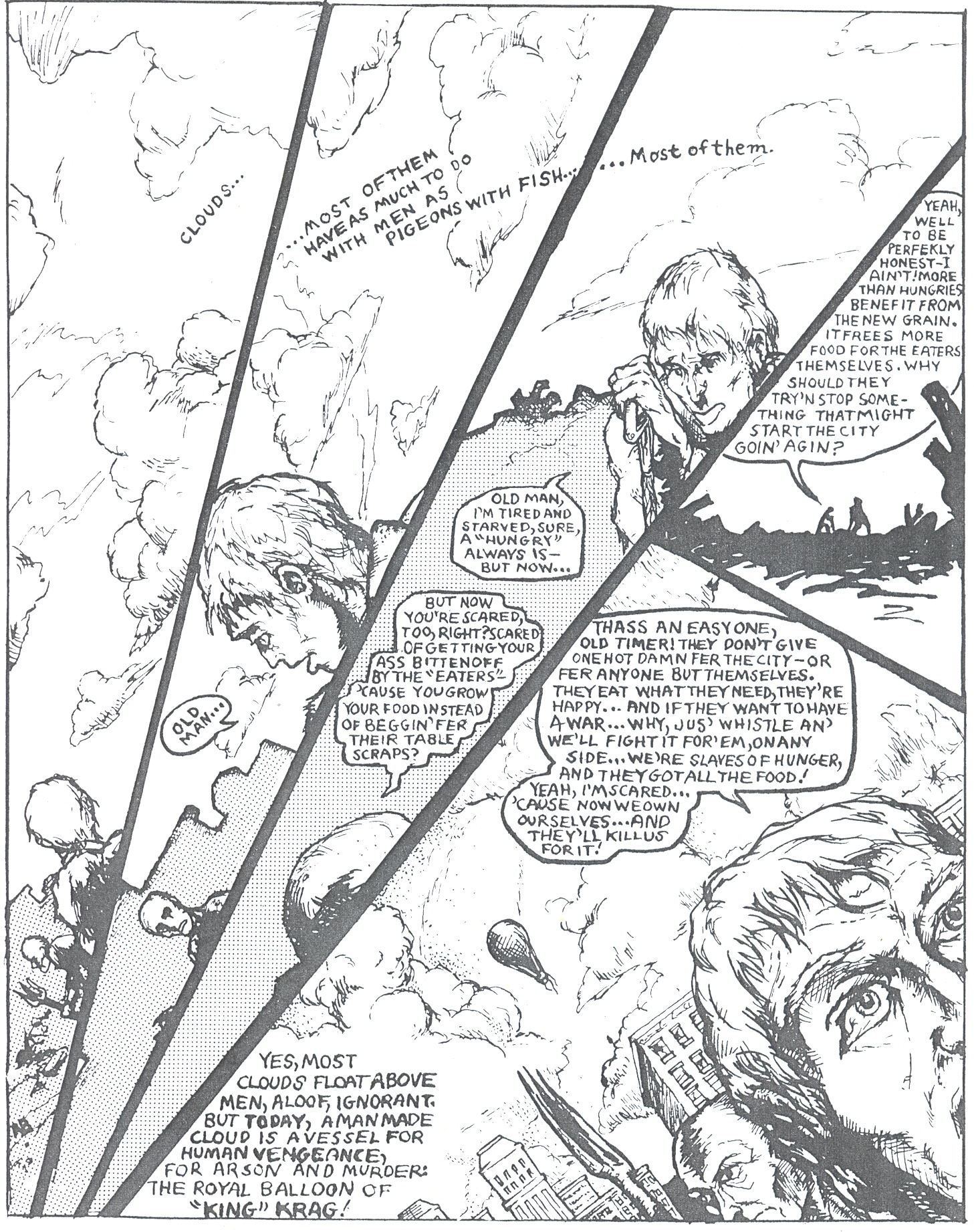

We know, of course, that the anxieties surrounding the Comics Code Authority’s strict guidelines opened up a space that mid-1960s underground comix would seek to fill. As Leonard Rifas states, “comix artists often tried to outdo each other in violating the hated Code’s restrictions,” deploying irony, satire, and caricature – notably, “extreme racial stereotypes” – to assert their freedom of expression.

In an interview from Ron Mann’s 1988 documentary Comic Book Confidential, R. Crumb explains:

We didn’t have anybody standing over us saying, “No, you can’t draw this. You can’t show this, you can’t make fun of Catholics… you can’t make fun of this or that.” We just drew whatever we wanted in the process. Of course we had to break every taboo first and get that over with, you know: drawing racist images, any sexual perversion that came to your mind, making fun of authority figures, all that. We had to get past all that and really get down to business.

Small press and indie comics creators continue to adhere to this countercultural checklist nearly sixty years later, gleefully undermining each new generation’s standards of good taste and decency with new artistic infractions. But Crumb’s approach to what he refers to as “absolute freedom” in the above quote does not adequately account for the risks taken by many African American artists and writers for whom the constraints, the taboos, and the violations differ. For me, then, examining indie comics and cartoonists in a larger contextual way means recognizing that there is more than just one Comics Code when it comes to race. And it means taking seriously the complex social and aesthetic tensions that black creators must navigate in order to exercise their own rights to free expression, even when they can’t get over or get past all that.

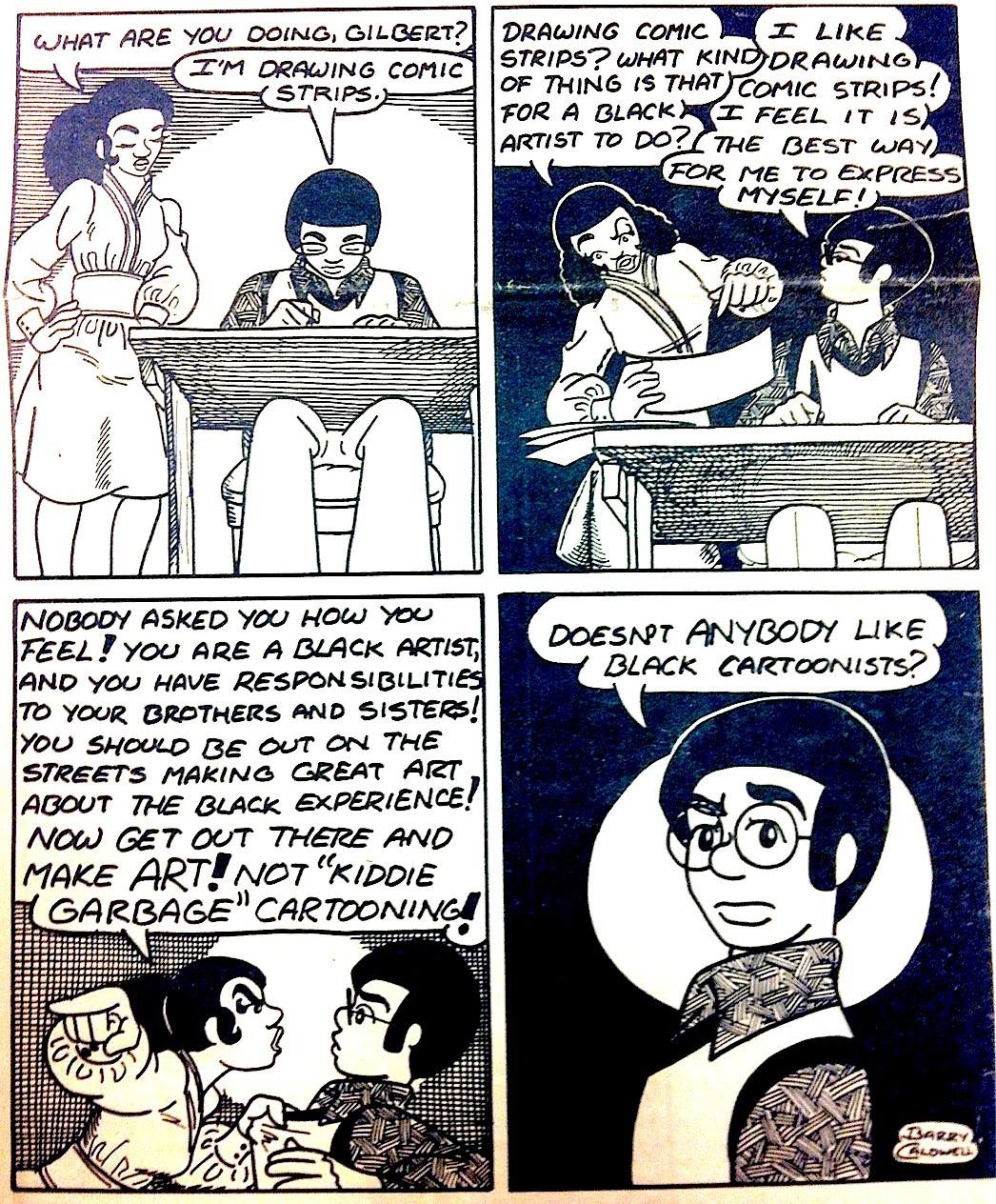

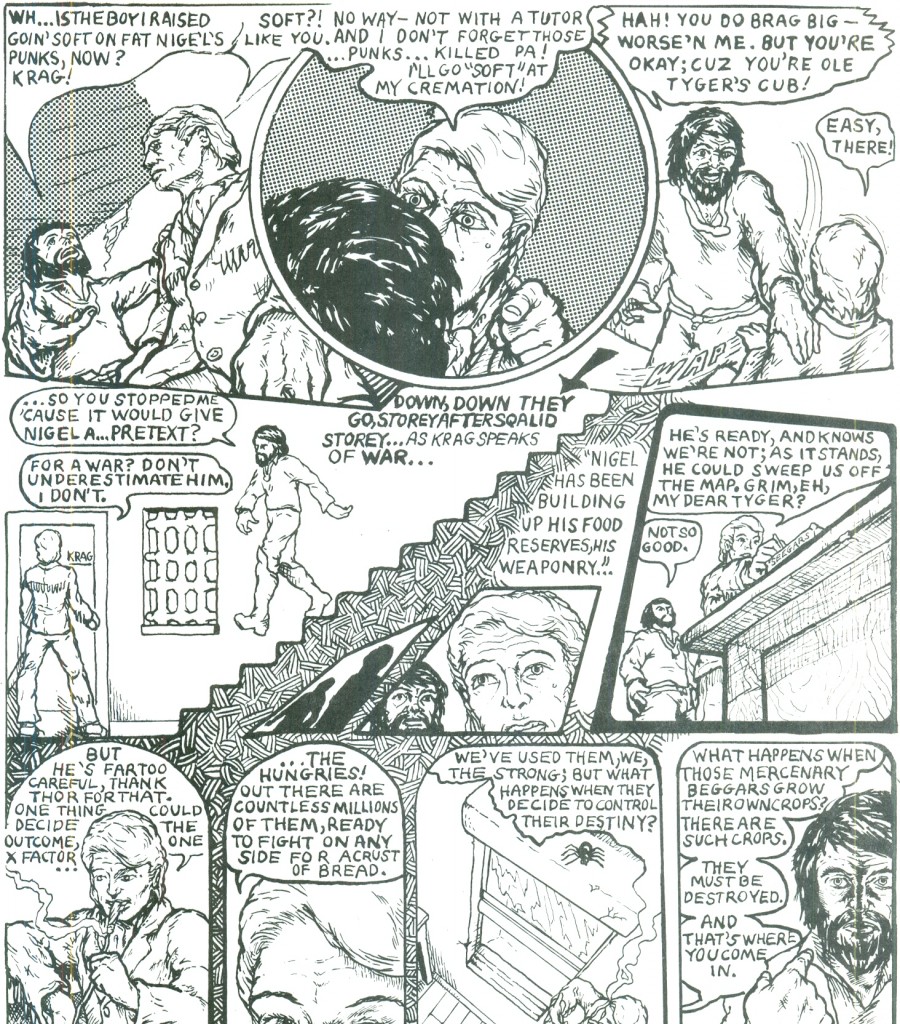

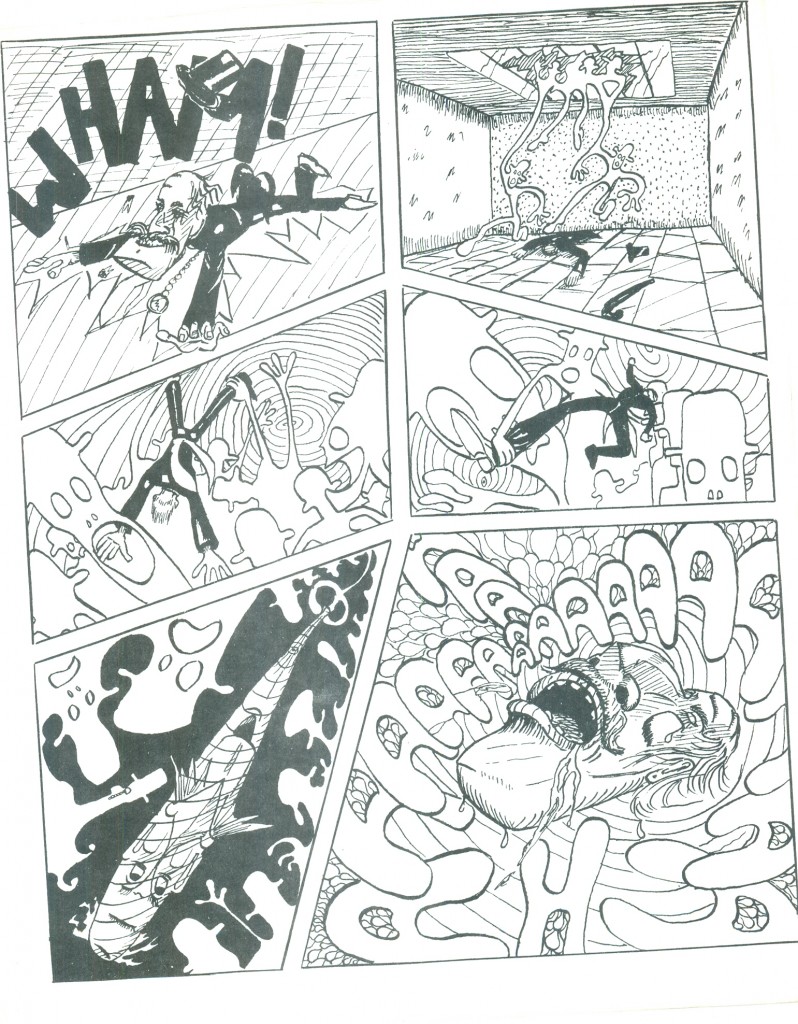

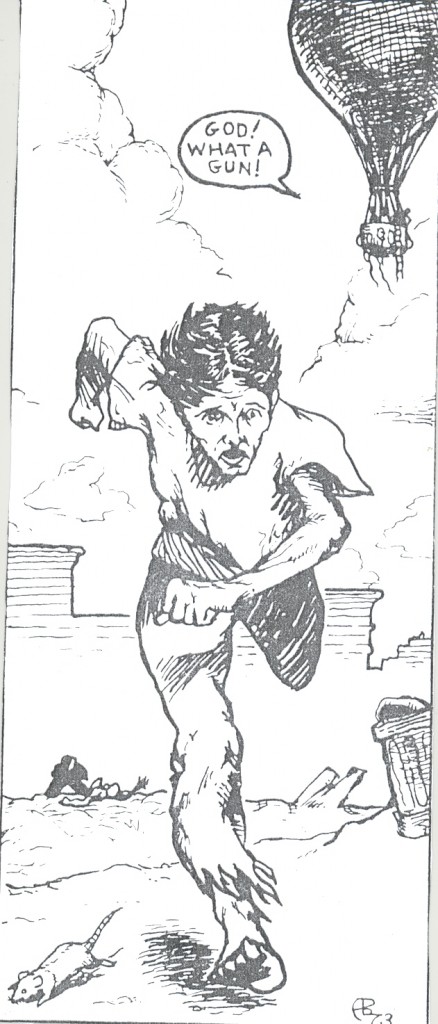

Cartoonist Barry Caldwell’s semi-autobiographical character Gilbert Nash is reprimanded in the 1970s strip above for making “kiddie garbage.” The regulating body standing over him in this instance belongs to an acquaintance that doubles as the physical manifestation of the cartoonist’s self-doubts. Her pointing fingers and exclamations intrude furiously into his drawing: “You should be out on the streets making great art about the black experience!”

Caldwell illustrates how an entrenched politics of racial respectability intersects with ongoing debates within black communities over the social function of art. Comics are derided by the woman in the strip as a frivolous medium through which white cartoonists are afforded the luxury of feelings, but a treacherous, irresponsible choice for a black artist with a greater obligation to his people. This is what is at stake when the chastising voice says, in other words: “No, you can’t draw this.” And yet four panels into exposing what is presumably a private exchange, Gilbert has already claimed his existence as a comic artist during the Black Arts Movement, rebuffing the viewer’s objectifying gaze with a question of his own. Taboo is drawing one’s self into being as an indie black cartoonist.

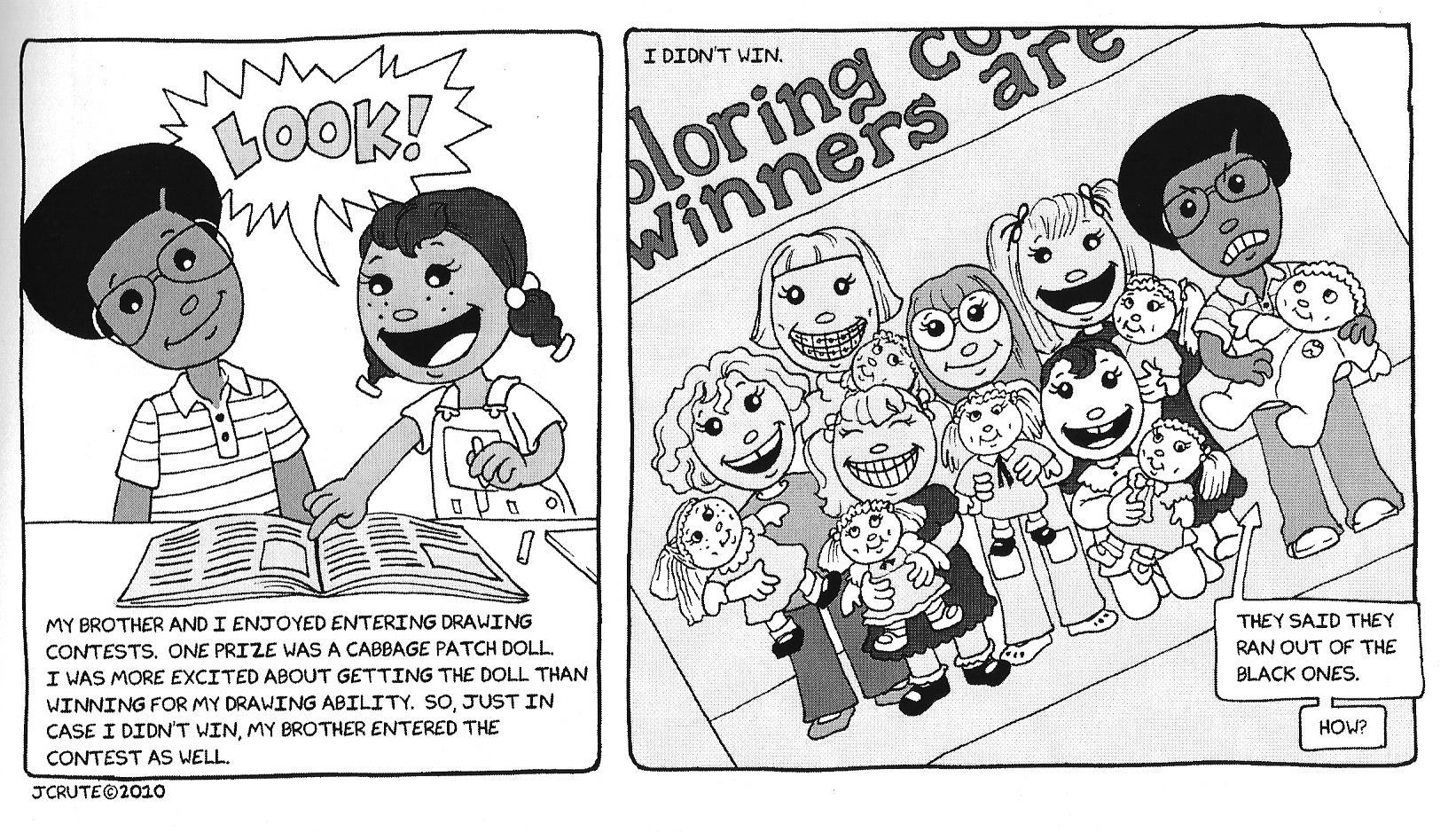

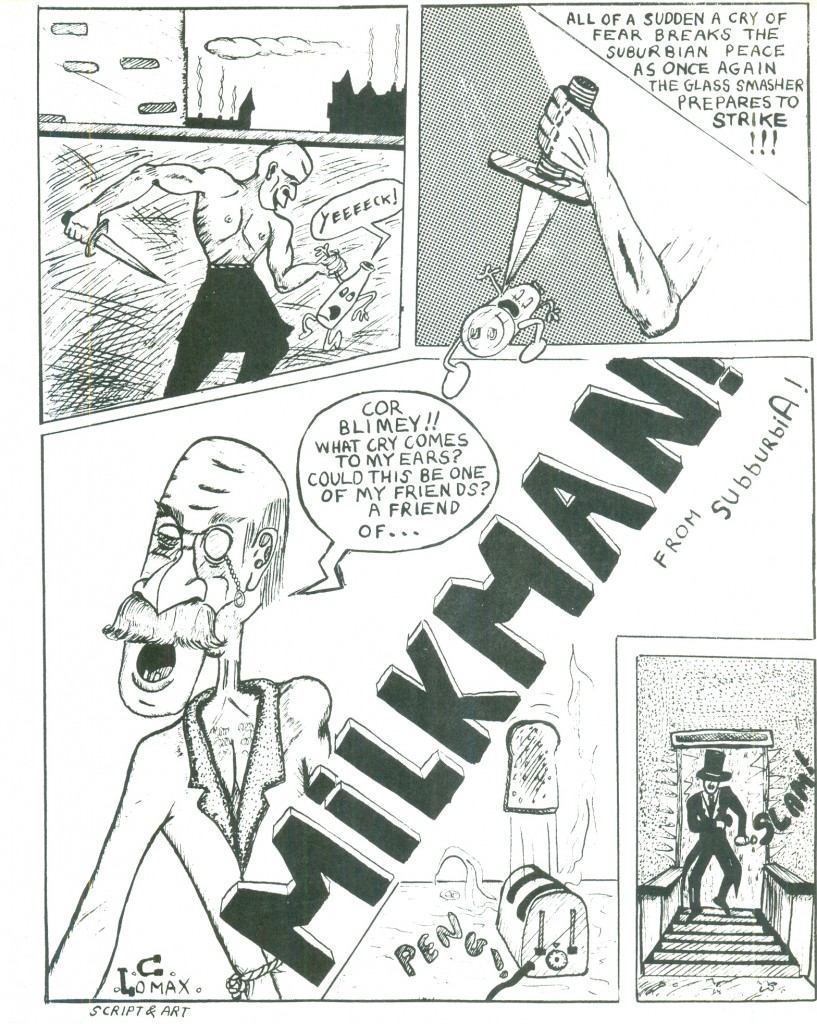

This is the context that shapes my reading of the comics of Jennifer Cruté. The two collected volumes of her comic strip, Jennifer’s Journal: The Life of a SubUrban Girl, feature autobiographical sketches of her upbringing in New Jersey suburbs as well as her life as a freelance illustrator in New York. With round, expressive black and white cartoon figures, Cruté’s characters appear to come from a charmed world where “ridicule or attack on any religious or racial group is never permissible.” The wide faces tilt back and break easily into open-mouthed grins and scowls. Her freckled persona wears teddy bear overalls, while an older brother’s Afro parts on the side, Gary Coleman-style. Like the cursive “I” that is dotted with hearts on the title page, the comic adopts a style more closely associated with the playfulness of a schoolgirl’s junior high notebook. The title foregrounds the space of socio-economic privilege and gentrification that her family occupies during the 1980s complete with Cabbage Patch Dolls, family vacations to Disney World, and copies of Ebony and Life side by side on the coffee table.

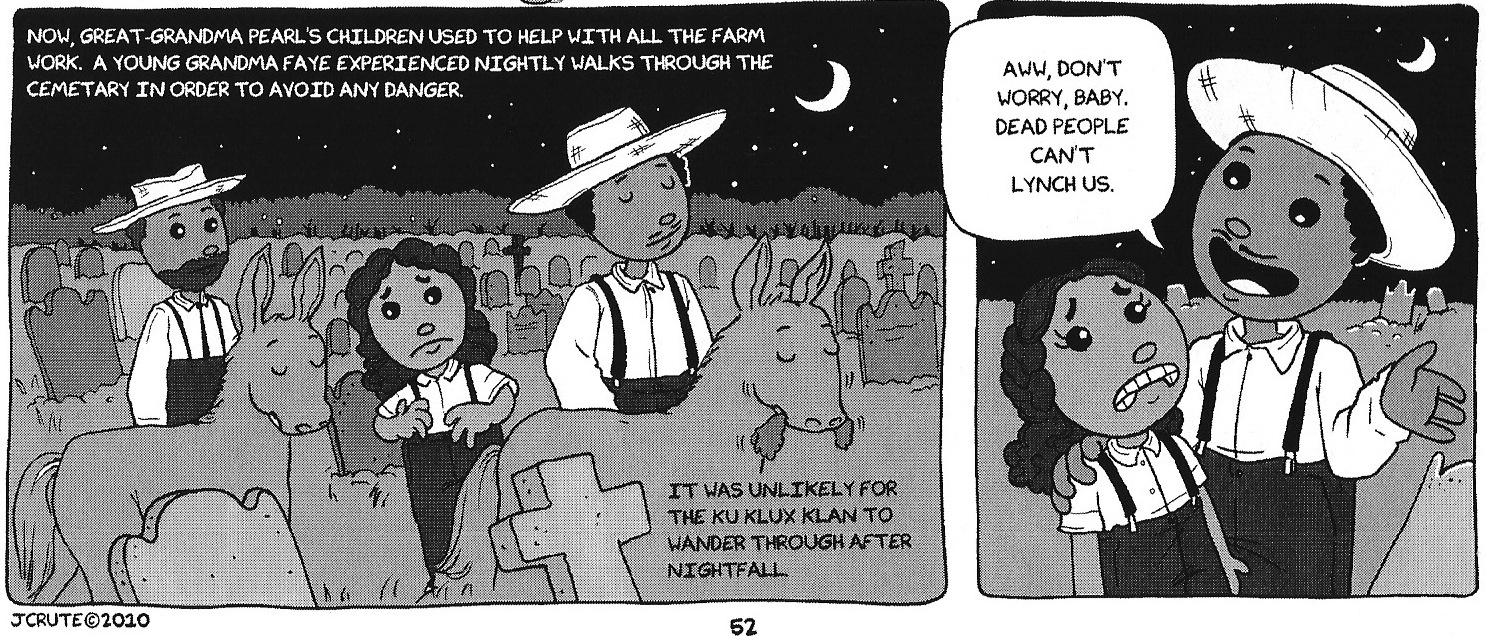

Race introduces a source of friction that impacts Cruté’s decision to represent her experience as a young black girl through caricature. There are plenty of comic strips that depict the lives of children, but much like Ollie Harrington, Jackie Ormes, or more recently, Aaron McGruder, Jennifer’s Journal uses children to explore the absurdity of racism and the means through which blackness is socially constructed. She traces her earliest affection for Kermit the Frog, for instance, to the episode of “The Muppet Show” when she mistook guest Harry Belafonte for puppeteer Jim Henson. And in scenes that take place down South, fears of lynching and racial violence dominate the story’s action, while the narrative turns to everyday micro-aggressions and more subtle humiliations to capture her own encounter with racism in the suburbs.

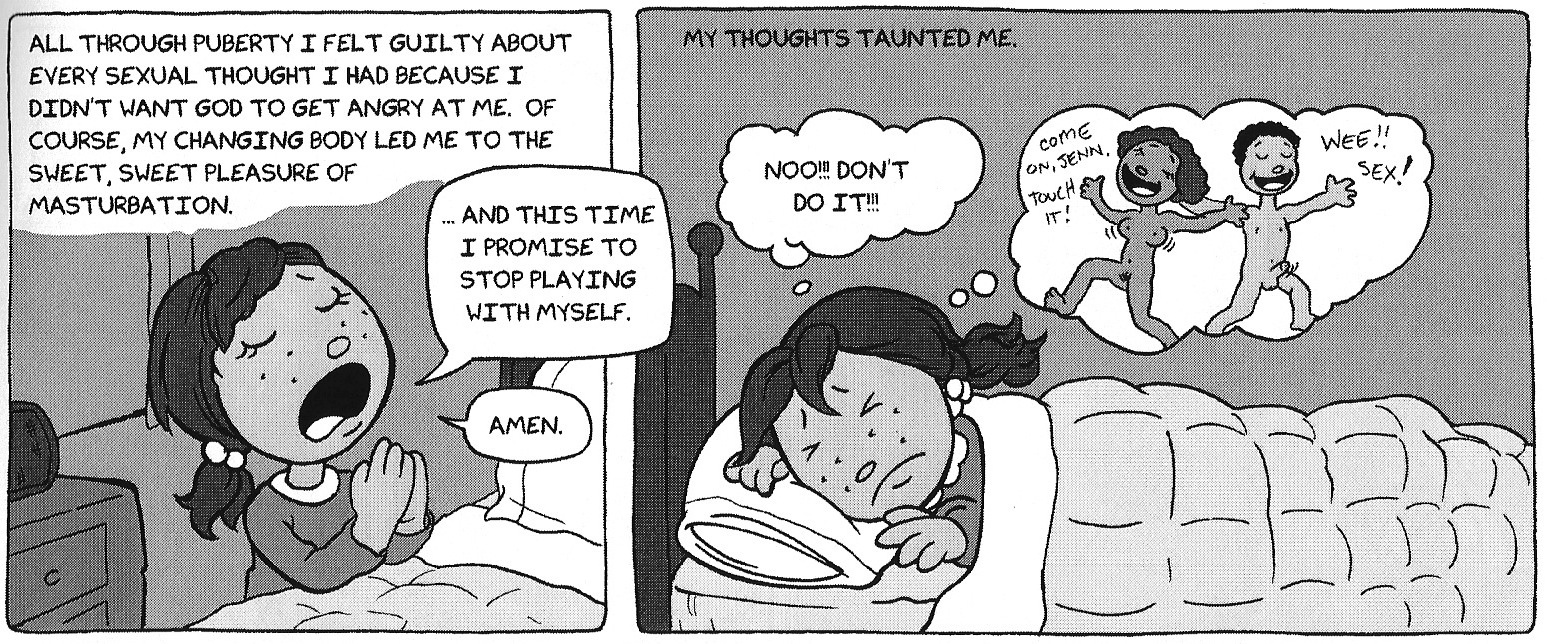

The first volume’s cover image further aligns Cruté’s work with the confessional mode of popular small press and indie comics; a young African American girl nervously pulls down the pants of a plush toy bunny, while surrounding her are other undressed stuffed animals posed in various sexual positions. The fact that young Jennifer’s inspiration comes from an art history book open to a painting of a nude Adam and Eve speaks to the notion that visual images have the power to confer an uninhibited sense of expressiveness and wicked curiosity. Likewise when her reflections turn to religion and sin, Cruté confesses her nightly struggle to abstain from masturbation. She portrays the temptation as she tries to go to sleep beneath a pictorial thought balloon that recalls the image from the book’s cover, although this time the nude Edenic bodies that entice her to “Come on, Jenn! Touch it!” are created in her own brown-skinned image.

My point here is that the push and pull of creative freedom and self-regulation play out in Jennifer’s Journal on multiple registers. Though warnings mark the front and back cover to alert readers that the book is “NOT recommended for children,” the comic’s aesthetic choices incorporate cautionary measures that gesture toward the kind of “instructive and wholesome” entertainment that the Comics Code Authority sought to preserve. In an author’s note, she writes: “I draw simple characters with round figures to soften the complex and contradictory life situations I depict.” But despite this stated intention, I can’t help but see a rewarding motley of signifiers in the comic – some that soften, others that rankle and surprise. The comic playfully mocks both the demand for racial respectability and the longing for a vision of reality that treats frank discussions about racism and sexuality as inappropriate.

I have tried to be careful not to suggest that black artists and writers are the only ones entitled to complex images of blackness in comics, nor are they the final arbiters of how best to represent and confront racism. As Darryl Ayo points out in his post about Benjamin Marra’s Lincoln Washington: “People are going to do what they’re going to do.” But as Darryl goes on to suggest, there should be a more meaningful, substantive awareness of historical context in our interpretations of comics that explore racial conflict. I believe we should also ask tougher questions about how and why particular notions of absolute freedom are idealized in underground, indie, and small press comics. And why there isn’t more room in these discussions for the “kiddie garbage” of Jennifer Cruté and the other creative risks that black comics creators are taking right now.