This first appeared on Comixology.

________________

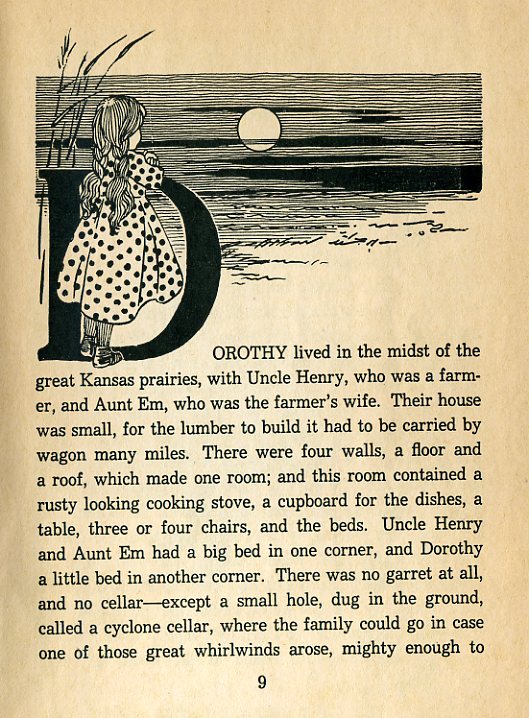

That’s the first page of the first chapter of The Wizard of Oz, written (of course) by L. Frank Baum, and illustrated by W.W. (William Wallace) Denslow. As you can see, Dorothy is leaning on the first letter of her own name, standing beside a Kansas wheat stalk. She stares into a mysterious fairie twilight…and not coincidentally, also seems to be staring into the book itself, with its own mysterious fairie treasures. Dorothy is about to enter the story, and she’s also the story itself; she’s an image and a name. You can’t show her without showing the start of the book.

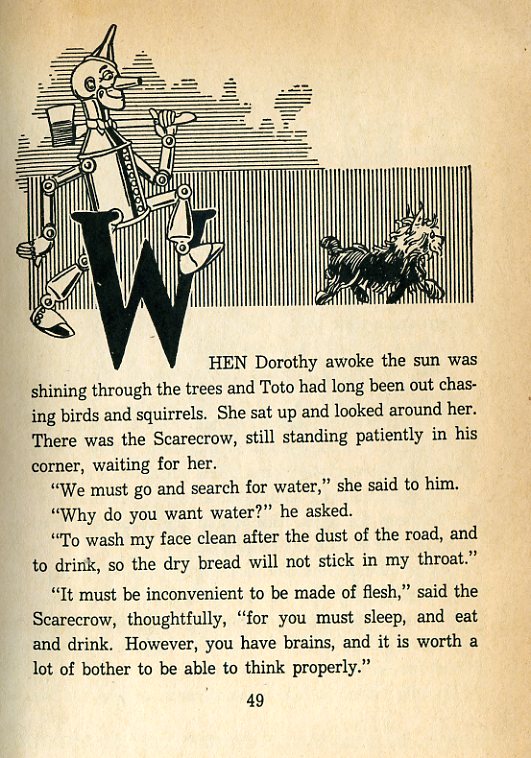

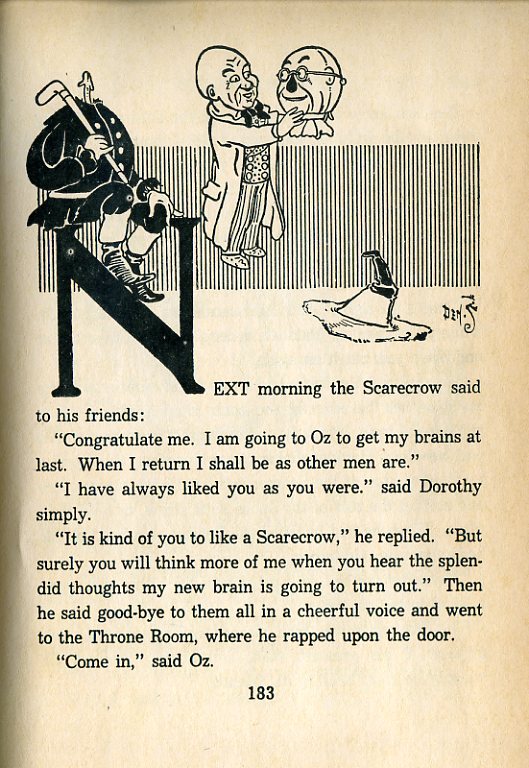

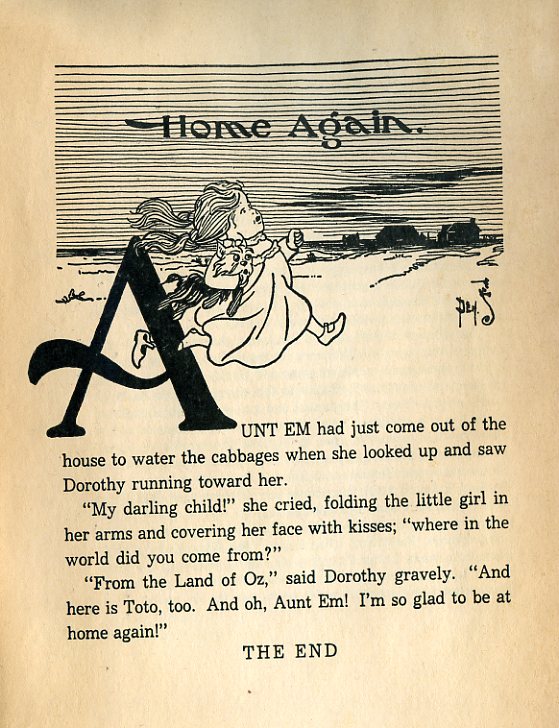

Denslow used illustrations like this, incorporating a letter into his picture at the beginning of each chapter.

In some sense, these are just flourishes; you don’t need the illustrations to follow the story, as you would in many comics. Yet, the intertwining of words and images fits Baum’s story unusually well. Rereading The Wizard of Oz in comparison with, say, The Hobbit or a more recent series like Patricia Wrede’s The Enchanted Forest, it’s striking how shallow Baum’s narrative is. Not that it’s not delightful or even moving — it’s both of those things. But Oz, the world itself, seems about an inch deep. You get the sense that Baum has thought only a sentence or so ahead of his protagonists, if that. The yellow brick road doesn’t so much lead Dorothy through the narrative as it skips rather desperately ahead of her. Ummm…creatures with bear bodies and tiger heads…and then, ur, flying monkeys, and…a city of china people! And next…creatures that shoot their heads like cannon balls! And the queen of the mice! Each section seems to come into being in the nick of time, just before Dorothy can put her foot down upon it.

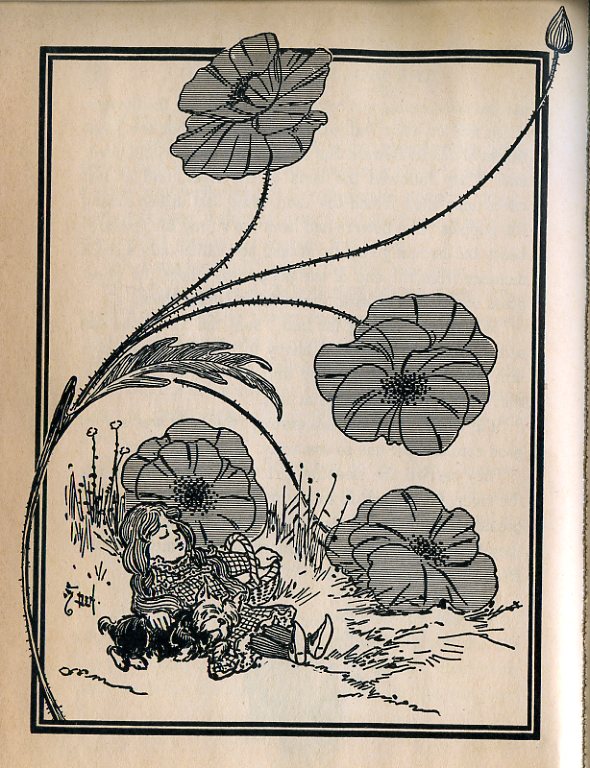

Partially for that reason, one of my favorite passages in the book is when Dorothy and her companions are in the poppy field. Dorothy and Toto fall asleep. The Tin Woodman and the Scarecrow can carry them, but the lion is too heavy, so they urge him to run ahead and get out of the field. So he “aroused himself and bounded forward as fast as he could go. In a moment he was out of sight” — running ahead of the story, and so vanishing into the poppies and dreams.

Literally, as it turns out. The others find the Lion

lying fast asleep among the poppies. The flowers had been too strong for the huge beast and he had given up, at last, and fallen only a short distance from the end of the poppybed, where the sweet rass spread in beautiful green fields before them.

“We can do nothing for him,” said the Tin Woodman sadly; “for he is much too heavy to lift. We must leave him here to sleep on forever, and perhaps he will dream that he has found courage at last.”

On the next page, there’s this striking illustration, showing Dorothy and Toto asleep and the giant, deadly poppies twining around them and breaking out of the panel borders. The poppies seem to be trying to reach and intermingle with the text on the facing page, as if to suggest the words are in Dorothy’s dreams and vice versa.

In that context, it’s worth noting too that the Tin Woodman’s hope for the Lion — “perhaps he will dream that he has found courage at last” — is exactly what happens. The wizard is revealed as a humbug…which is to say, he’s a storyteller.

The Scarecrow’s body rests on the letter “N” while the wizard takes the head to stuff it with brains — or, more precisely, with the word “brains.” The text is what surrounds the scarecrow and what’s going inside him, just as the Lion gets not courage, but a dream of courage. Which is, as it turns out, the same thing.

In his 1971 book The World Viewed, critic and philosopher Stanley Cavell argued that for the film version of The Wizard of Oz:

The unmasking of the Wizard is a declaration of the point of the movie’s artifice. He is unmasked not by removing something from him but by removing him from a sort of television or movie stage, in which he has been projecting and manipulating his image. His behavior changes; he no longer can, but also no longer has to maintain his image, and he demonstrates that the magic of artifice in fulfilling or threatening our wishes is no stronger than, and in the end must bow to, the magic of reality….

Whether or not this is the case for the film, it seems much less clear-cut in the book. Oz is revealed as a story teller, but he doesn’t stop telling stories, and those stories don’t stop being real. In fact, he seems a better wizard once he’s been exposed, not because he’s more real, but because — what with dispensing brains, hearts and courage — his humbug is more convincing. How can you tell the magic of artifice from the magic of reality anyway? How can you separate what you say from what you see?

That’s the last page of the book. Dorothy has skipped across the desert back to Kansas with her magic silver shoes, and they fall behind her. You can see one of them has fallen off already; it’s dropped in the “A”. Except…when I first looked at this drawing, I thought the shoe was Dorothy’s foot; it took me a moment to realize that it had gotten detached. Which seems apropos. Dorothy’s still in the text, even after all these years. The home she comes back to isn’t any more real than the words “Home Again” which float like a sign-post above the twilit Kansas sky. Which is to say, both aren’t real, and are.