In his post last week, James Romberger argued that the “offensive flaw” of Watchmen is its suggestion that a woman could forgive, and even love, her rapist.

Sally kissing the photo of the late Blake amplifies the flat note in what is otherwise one of the most carefully and sensitively composed comics ever done. In a medium predominantly directed to males, an often overtly misogynistic form oblivious to the consequences of sexual violence, this rare realistic depiction of rape in comics comes to represent a offense a woman could forgive, that she even might even come to love her rapist.

James is certainly correct that the trope of woman-falling-for-her-rapist — the conversion rape — is a standard of misogyny. As I’ve noted before, the ur-conversion rape is probably the notorious scene in Goldfinger where James Bond overpowers Pussy Galore and fucks her. Afterwards, Pussy Galore abandons her lesbianism and betrays her boss, risking her life and the lives of her whole lesbian posse for the love of Bond’s magic penis.

what’s especially offensive about this whole scenario is the extent to which Ms. Galore is so completely beside the point. The rape and transformation is never about her; in fact, we don’t ever get a sense of her as a character except that she’s tough and independent, and then, suddenly, not so much. She falls for Bond because he’s just so darn overwhelmingly attractive, and she abandons her (never quite stated) lesbianism as if she were doffing a hat. There’s no actual psychological progression attempted; it’s just, insert phallus, hello enlightenment. The whole point of the encounter is, in fact, to annihilate her as a character; in entering her, Bond replaces her will with his own, and she becomes simply his catspaw. It’s the crudest kind of male power fantasy, and one which is more than a little pitiable, suggesting as it does a desire to fuck a mannequin, rather than a real person.

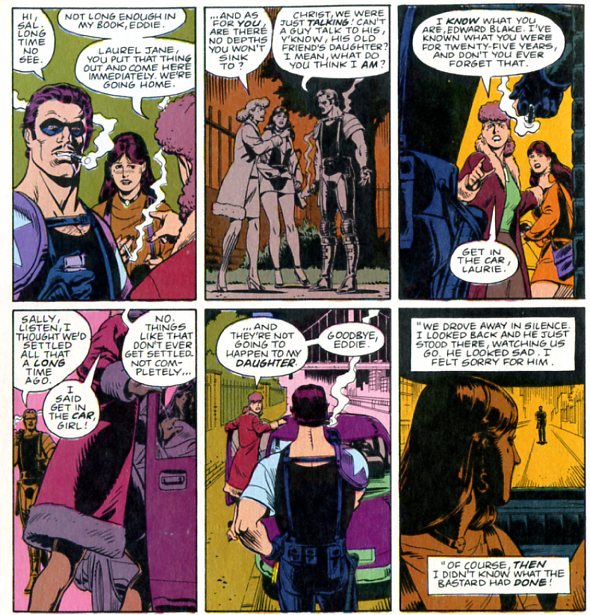

The Bond/Pussy Galore conversion rape is undoubtedly misogynist — but it’s also really, really different from the rape in Watchmen. In the first place, there’s nothing romantic or pleasurable about the sexual violence that Sally experiences. On the contrary, Blake’s assault is bloody and miserable. He himself is anything but cool; Gibbons portrays him pathetically pulling his pants up afterward, and then getting beaten to a pulp by the Hooded Justice.

Moreover, Sally is not converted by the rape. On the contrary, she never forgives Blake.

She hasn’t forgotten, she hasn’t decided what he did was okay. He’s a monster, she knows it, and she’s never going to let him have anything to do with her daughter.

Of course, the part that gets James, and that he feels is misogynist, is that Laurie is Blake’s daughter too. Sally did not forgive him, but she did love him.

James feels that that is problematic. In part, he seems to feel that it is problematic because it is unrealistic (“this rare realistic depiction of rape in comics comes to represent a offense a woman could forgive, that she even might even come to love her rapist.”)

But is Sally’s reaction unrealistic? Women do often love, or are intimately attached, to the people who abuse them, whether husbands or boyfriends. This is an uncomfortable truth, especially for a feminist vision that puts a premium on empowerment and autonomy. Sally Jupiter is certainly not perfectly self-actualized; there’s no question about that. But because she’s not perfectly self-actualized, does that mean she and her choices are necessarily wrong or misogynist?

In James’ reading, Sally’s love becomes the misogynist smoking-gun; the love is wrong. I don’t accept that. It’s not Sally who’s wrong. It’s Blake. It’s not the love that’s at fault; it’s the violence.

James says that:

Even more offensively, Snyder in his film made the fact of Laurie’s very existence through Sally’s forgiveness be the salvation of the world. This concept unfortunately lurks in the book…

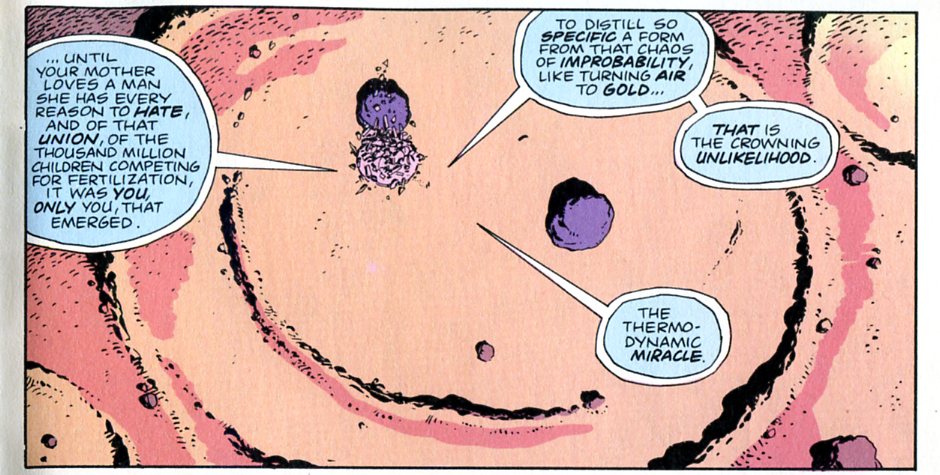

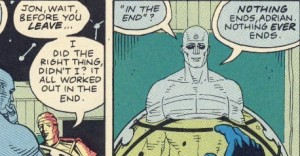

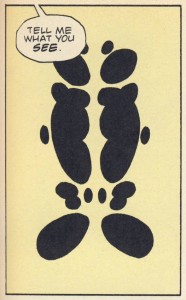

I’m relieved to discover that I’ve almost completely forgotten Snyder’s crappy film. In the book, though, Laurie’s existence is indeed seen as a miracle (though not necessarily as the salvation of the world, as my brother points out). As Dr. Manhattan puts it:

So yes, Sally’s love (though not, as I said, her forgiveness) is seen as transformative, and even beautiful. And it is seen as transformative and beautiful in large part because it produced Laurie, who Sally loves, and who Jon loves.

I think James in part sees Sally’s love as a flaw because he sees it as mitigating, or validating the rape. But I don’t think that’s the case. Just because something good comes from evil doesn’t make evil good. Paul Celan’s poetry is wonderful, but it doesn’t validate or recuperate the Holocaust. Or, as C.S. Lewis says in Voyage to Venus, talking about the fall from Eden:

“Of course good came of it. Is Maleldil a beast that we can stop his path, or a leaf that we can twist His shape? Whatever you do, He will make good of it. But not the good He had prepared for you if you had obeyed Him. That is lost for ever. The first King and first Mother of our world did the forbidden thing; and He brought good of it in the end. But what they did was not good; and what they lost we have not seen. And there were some to whom no good came nor ever will come.” He turned to the body of Weston. “You,” he said, “tell her all. What good came to you? Do you rejoice that Maleldil became a man? Tell her of your joys, and of what profit you had when you made Maleldil and death acquainted”…

The body that had been Weston’s threw up its head and opened its mouth and gave a long melancholy howl like a dog….”

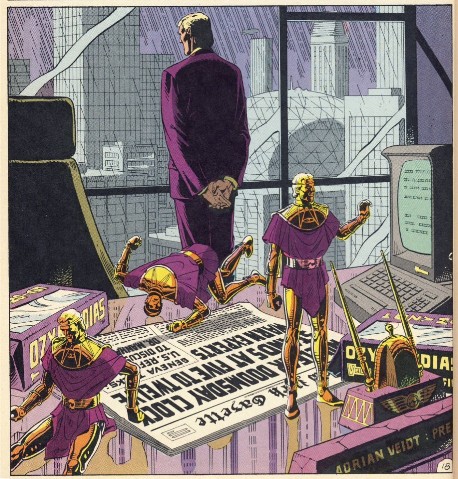

That could be Blake at the end giving that howl, almost. Certainly, he dies ignominiously and alone, having lost even the comfort of his amorality. Laurie, as a living manifestation of her mother’s love, is a standing rebuke to Blake and his life. If Laurie is a miracle, then the Comedian’s cynicism and nihilism truly mean nothing. This is not to say that Moore and Gibbons, or even Laurie herself, entirely reject the Comedian’s evil or his violence. But it is to say that, to the extent that Watchmen does reject it, it’s because of, not despite, Sally and her choices.

I don’t mean to say that those choices are ideal. Sally herself doesn’t think her choices are ideal. But just because a woman fails to make ideal choices, and just because she does not respond to violence with hate (or at least not only with hate), doesn’t make her a failure. If feminism requires perfect women, there won’t be any feminism. Sally may be a flaw, but humans aren’t gems. Flaws don’t make them less precious.