This piece first ran on Splice Today.

________________________

Kate Beaton is the rock star of web cartoonists. Hark a Vagrant may not be the most popular strip online—I doubt it’s overtaken Randall Munroe’s xkcd or Mike Krahulik and Jerry Holkins’ Penny Arcade. But, especially with Achewood on hiatus, Hark a Vagrant is probably the hippest web strip around, combining popularity with almost universal critical acclaim. If you’re not familiar with webcomics, there’s a good chance that Kate Beaton will be one of the two or three examples of the genre that you’re familiar with.

Beaton came out with a collected book of her strips last week published by Drawn and Quarterly. The most striking thing about seeing the strips on the page is, perhaps, how un-striking it is to see the strips on the page. In the dim, pre-historic Internet dawn of 2000, Scott McCloud in Reinventing Comics proposed that the Internet would allow comics to spread and morph into fabulous shapes. Creators could take advantage of what McCloud called an “infinite canvas” to produce sprawling images that scrolled across multiple screens.

Some creators have picked up on the hint—McCloud himself has made some comics in this vein—but for the most part, webcomics look a lot like newspaper comics. Beaton’s certainly do; almost all of her strips are three or four panels, like a daily, or else two tiers of three-or-four-panels, like a Sunday. Occasionally she’ll have a slightly different format: for instance, a strip about Vikings collecting souvenir-illuminated manuscripts from sacked monasteries is eight panels arranged as two pages of four-panel blocks. But that’s about as adventurous as the layout gets. Artists like Bill Watterson and Winsor McCay were eager to use every inch of space they had for lush landscapes across which action rolled and sprawled in lavish, kinetic detail. In theory Beaton has a lot more room than Calvin and Hobbes, and even more than Little Nemo, but she’s not interested. Instead, like most web cartoonists, she seems comfortable in the small cramped boxes, which she fills mostly with people standing around with their speech bubbles.

It’s not that the web form has no effect on Beaton; it’s just that you need to squint a little to see them. Most significantly, perhaps, is that you don’t actually need to squint. Comics in the paper have gotten smaller and smaller, encouraging the proliferation of strips like Dilbert—hideously ugly, but readable at even microscopic size.

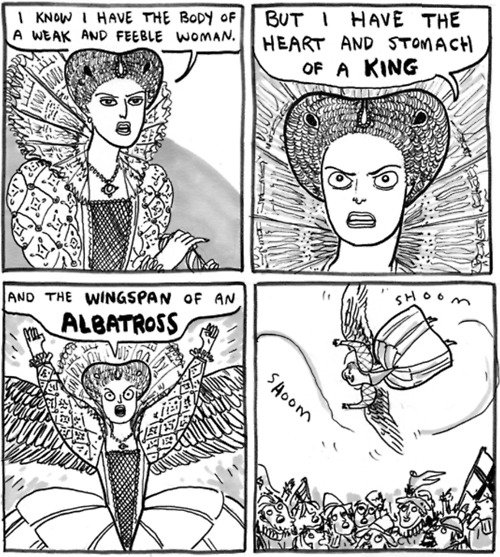

Many webcomics, like Achewood or xkcd, also feature rudimentary art, but Beaton’s work is much more accomplished. In a strip showing the battle between a giant squid and the Nautilus, the bigger-than-newspaper-size panels give Beaton a chance to play with scale. In one panel, a giant tentacle wraps around one of the men; in another the squid sidles up to the sub. Similarly, in a Sunday-shaped-strip about Queen Elizabeth, Beaton draws the first tier of panels in increasing close-up, allowing us to enjoy the tightly-drawn pattern on Elizabeth’s headdress. Then in the second tier, we pull back, as Bess declares she has the wingspan of an albatross, and goes swooping up, up and over the landscape, until she’s just a butterfly-like squiggle in the sky. It’s not a flashy effect, but it’s nicely done, and it would be difficult-to-impossible to pull off in the space constraints imposed by newspapers.

But Beaton is mostly a creature of the web not so much in her drawings as in the topics she chooses and the way she approaches them. Traditionally, most strips have featured recurring characters (like Peanuts). Some web strips work that way too, but there are others which are more conceptual…. or more gimmicky, depending on how charitable you’re feeling. Ryan North’s Dinosaur Comics, for example, re-uses the same clip art dinosaur art in the same six panels every day, altering the text to create different gags. Dan Walsh’s amazing Garfield Without Garfield alters a Jim Davis strip every day, removing the eponymous cat in order to focus on Jon Arbuckle’s life of emptiness and absurd despair.

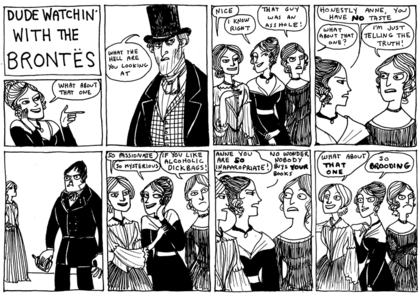

Beaton’s approach isn’t as formulaic, but it’s still (for the most part) a formula. Rather than inventing her own story lines, she takes characters from literature and history and writes jokes around them. So in “Dude Watchin’ With the Brontës,” Emily and Charlotte enthuse about brooding, violent men (“So passionate.” “So mysterious.”) while Anne points out that these brooding, violent men, are as she says, “alcoholic dick bags.” In another memorable strip, a badass Wonder Woman gets a cat out of a tree by viciously lassoing it and nearly terrifying it to death; in another Marie Curie goofs around by putting little chunks of radium over her eyes.

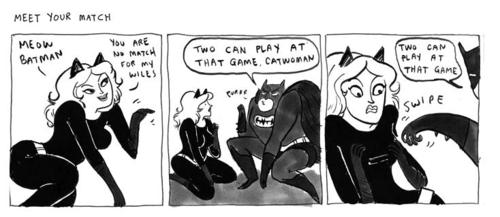

The joy of Beaton’s work is seeing familiar figures given a half twist and recontexualized—Dracula’s wives discussing women’s rights, or Moses losing the respect of his people because he’s dressed in sandals and socks. As such, her comic fits right in on the web, which has an insatiable love for creating the new out of the bits and bytes of the old. Beaton’s cartoons are like mash-ups or fan-fiction. They’re perfect for an environment in which large communities of people who love, say, Nancy Drew, are primed to send each other links to the new cartoon where Nancy dons a KKK mask, or those who love superheroes are ready to tweet about the strips featuring sexy Batman. Beaton cartoons all feel like Internet memes waiting to happen.

When Internet memes are great, it’s because of their unassuming absurdity; the brilliant ease with which, for example, Beaton makes Charlie the reluctant winner of a trip to a turnip factory, or the quick, biting snark with which she portrays the perfect Dickens heroine as a bland nonentity who looks like her brains have been scooped out with a melon-baller.

When Internet memes are not so great, it’s because of that same swiftness and effortlessness—they can come off as glib. That’s the case for Beaton’s work too, especially over the course of an entire book. One historical figure talking like a valley girl is very funny; when it’s the patois of Elizabethan peasants and Nordic adventurers alike, though, it can start to seem like a tic. Similarly, Beaton’s “isn’t history/literature funny, huh?” schtick gets tiresome after awhile—like those emails from your friend who just can’t help sending you every single “hilarious” link that the Web happened to spit out that day. When Beaton’s good, she reminds you of Gary Larson; when she’s not so good, it feels like Gary Larson domesticated for NPR.

Still, if every hilarious link you ever got was as funny as Beaton’s cartoons generally are, the world would be a happier place. If the Hark a Vagrant collection is, like the Internet, occasionally disappointing, it is also, like the Internet, often delightful, and ultimately worth paying for.