Individualism is a mature and calm feeling, which disposes each member of the community to sever himself from the mass of his fellows and to draw apart with his family and his friends, so that after he has thus formed a little circle of his own, he willingly leaves society at large to itself. Selfishness originates in blind instinct; individualism proceeds from erroneous judgment more than from depraved feelings; it originates as much in deficiencies of mind as in perversity of heart.

– Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America (1835)

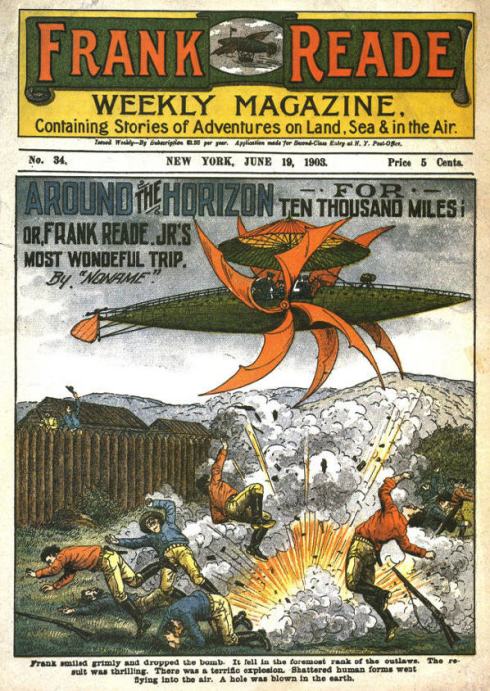

Superheroes are an American invention, because America is the land of entrepreneurs.

– Life, a.k.a. Chaim Lazaros (2011)

In the first four chapters of this study, I have concentrated on Europe exclusively as a source for the ideas and tropes that would lead to the modern figure of the superhero. Yet few would contest that the latter is overwhelmingly an American phenomenon; why, then, my emphasis on the “old continent”?

In an age when so many either bemoan or celebrate American cultural hegemony worldwide, it is well to remember that the United States was, until the 20th century, very much a backwater in culture– even in popular culture. American pop was generally derivative, where it existed at all; its melodramas came from the stages of London, its novels from Britain and France.

This was due to several historic reasons that were slow to fade away. The new republic was sparsely populated and thus had difficulty sustaining strong media industries; its language was the same as that of one of the cultural giants of Europe, Britain, assuring that country’s dominance. And until 1891 — and the adoption of the International Copyright Act — the United States offered copyright protection to U.S. citizens or residents alone.

The last fact was pernicious both to foreign authors such as Dickens (who complained bitterly about legal American piracy of his books), and to native ones. Why should a publisher spend money on an American writer of uncertain appeal, when he could publish a best-seller such as Jules Verne for free?

(It was a doubly bad deal for the American authors: they received no payment for books published abroad.)

This explains why the factors leading to the emergence of the superhero — the notion of the superman, science fiction, crime fiction, and so on– were overwhelmingly European in origin.

And yet it was America that gave birth to the superhero, as we understand it.

Why?

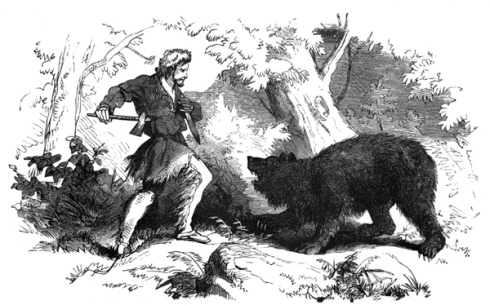

The unusual length of the claws, foot, stride, etc., filled Crockett with hope that the bear was a grizzly; a species with which he had never yet measured his prowess, though long anxious for the opportunity. — from The Bear-Hunter; or, Davy Crockett as a Spy

The two quotes that open this chapter offer a clue.

De Tocqueville, by David Levine

Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–1859), still considered today one of the greatest analysts of the United States and its society, was — as his quote shows — suspicious of individualism; he also noted democracy’s ability to counter its more invidious manifestations. He saw as well that nowhere in the world was individualism as prized as in America ( at least in theory; he also remarked on the great pressures to conform with received opinion.)

On paper– on the gaudily colored pulp paper of the comic book — the superhero is the ultimate fantasy of the individual, beholden neither to the laws of society, nor to those of physics.

And who is the other quote’s author, Chaim Lazarus (1984- )?

He’s the RLSH (Real Life Superhero) known as Life:

… and the founder of Superheroes Anonymous, a team-up of dozens of New York-based, masked and costumed RLSHs specialised in battling injustice by distributing food and necessities to the homeless.

His remarks about American entrepreneurship dovetail with de Tocqueville’s observations. The great myth of the American — a myth all the more potent for its kernel of truth– is that of the can-do lone wolf, the pioneer, the tamer of wilderness; of the fur trapper and the dot-com starter upper, the inventor, the self-made-man, the superhero.

And this myth had its roots established as long ago as the 18th century.

‘I want Elbow Room!’

This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact…print the legend.

— Dorothy M. Johnson, The Man who shot Liberty Valance

Publishing in colonial America was, as mentioned above, dominated by imports from Britain; the few native publishers were booksellers, bringing out the occasional volume to round out their inventory.

This changed during the War of Independance; however, the young republic’s offerings tended to be imitations of British originals. But one bestseller went against this trend, introducing a new sort of hero suited for the growing country:Daniel Boone.

Boone (1734–1820) was a real person. Over his long life, he was a pioneering settler of Kentucky; fought the French, the British, and the Shawnee; and ended as a settler in Missouri. His was an active, often violent life, marked both by adventure and tragedy, studded with both success and abject failure.

A life that was to be transmuted into legend, at the hands of one man: authorJohn Filson.

In 1784, Filson published The Discovery, Settlement, and present State of Kentucky, and one long chapter (based on interviews) was given over to the career of Daniel Boone. The material was factual, but rewritten in a florid, excited style alien to the laconic frontiersman. The book was a hit, and the Boone chapter was excerpted, expanded, and published separately. It was a sensation, much to its subject’s bemusement.

Here was a hero for the New World. Wrestling with bears, alternately fighting and being adopted by Indian tribes, free to stalk the virgin wilderness unencumbered by the sullen strictures of civilisation! Just the thing for the leisure reading of farmboys mired in drudgery, or city clerk‘s apprentices dully laboring in their offices. At any moment one could cast off the chains of societyand stride forth into the wonder and adventure of the frontier! (And kill lots of Injuns!)

This was a fantasy, of course — settling new land meant preparation, capital, and years of backbreaking, boring work. Boone himself spent decades embroiled in lawsuits over land title. But it was a fantasy that resonated strongly. It evoked one of the most powerful allures of American life: the possibility of re-inventing oneself.

(Boone resented this depiction of him as some sort of noble savage: “Nothing embitters my old age like the circulation of absurd stories that I retire as civilization advances….” He would also be appalled at future depictions of him as a bloodthirsty Indian killer. Boone fought Indians, but also dwelt among them in peace and was adopted by the Shawnee nation.)

For the past two hundred years, Daniel Boone has remained a mainstay of American pop culture.

Another frontiersman, supposedly of the same mould, was Davy Crockett(1786–1836) of Tennessee, whose legend outshines even Boone’s. This may be mostly due to his hero’s death at the siege of the Alamo in the Texan War of Independance; but also, largely, to Crockett’s shrewd cultivation of his image. He was, after all, a politician.

“In one word I’m a screamer, and have got the roughest racking horse, the prettiest sister, the surest rifle and the ugliest dog in the district. I’m a leetle the savagest crittur you ever did see. My father can whip any man in Kentucky, and I can lick my father. I can outspeak any man on this floor, and give him two hours start. I can run faster, dive deeper, stay longer under, and come out drier, than any chap this side the big Swamp. I can outlook a panther and outstare a flash of lightning, tote a steamboat on my back and play at rough and tumble with a lion, and an occasional kick from a zebra.” – Speech of congressman David Crockett at the House of Representatives, as reported in DavyCrockett’s Almanac

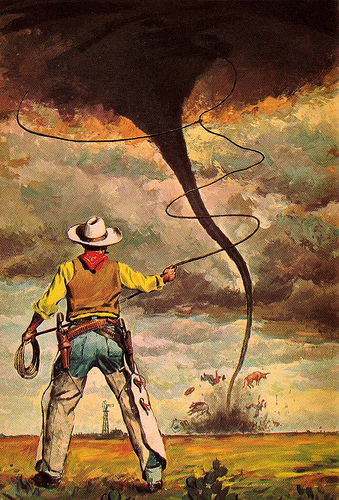

The above brag fits squarely into a tradition of American folkore and pop culture: the ‘tall tale’, often presenting the ridiculously impossible exploits of supermen: the cowboy Pecos Bill, who lassoed a tornado; or the giant lumberjack Paul Bunyan, who created the grand Canyon by dragging his pickaxe behind him.

Pecos Bill lassoes a twister. Yee-haw!

These tales show features not dissimilar to those of the later adventures of Superman or Captain Marvel; the popular imagination was thus primed for superpowers and superheroes.

Boone, Crockett, and other frontier adventurers such as Jim Bowie were fodder for chapbooks, pamphlets, and almanacs. Boone was also the model for the hero of America’s first international hit fiction: Natty Bumppo.

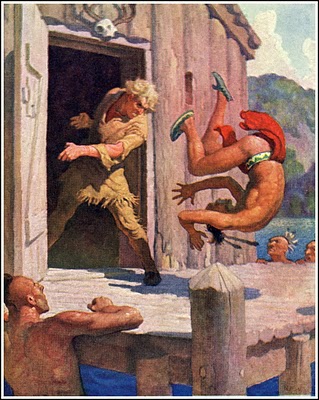

The Deerslayer, illustrated by N.C.Wyeth

James Fenimore Cooper (1789–1851) wrote the novels grouped as the Leatherstocking Tales, chronicling the woodsman Bumppo’s adventures in colonial America; the best-known remains The Last of the Mohicans (1826). This was one of the best-selling novels of the 19th century, both in the States and in Europe.

It’s intriguing to note that Bumppo, throughout the books, is known by many names: Leatherstocking, Deerslayer, Pathfinder, La Longue Carabine. In America your identity was fungible; you could remake it as you pleased. Small wonder the next century’s superheroes briskly adopted sobriquets. Thus Clark Kent becomes Superman, Bruce Wayne Batman, Steve Rogers Captain America. (And society at large is depicted as remarkably complaisant in accepting these names, whereas in the real world such sobriquets are generally bestowed by the press– rarely in complimentary terms, sports figures apart.)

The Leatherstocking tales were published as quite respectable, middle-class oriented novels, though they attained vast popular acclaim. However, there wasa growing ‘sub-literature’ of a less respectable cut that was poised to exploit the opening of the frontier and develop one of the most successful popular genres in history: the Western.

Go West, Young Man, in your Mind

Washington is not a place to live in. The rents are high, the food is bad, the dust is disgusting and the morals are deplorable. Go West, young man, go West and grow up with the country.

Thus Horace Greely, in an 1865 editorial in the New York Tribune. Although the third sentence is what has come down to us as a much-repeated quote, it’s instructive to pair it with the first and second ones. Greely was as much blasting the new urban America as praising the West qua arena of the nation’s future.

We mythologize the United States of the first decades after the Civil War as the scene of a vast epic of westward expansion…buffaloes, cowboys, mining camps, noble Sioux braves, gun-toting outlaws, wagon trains of settlers– all the colorful bric-a-brac of the legend of the West.

But legend it remained, though again, as with all legends, there was a grain of truth to it around which accreted romance and glamor, as nacre accretes round a grain of sand to make a pearl.

The salient change in late 19th century America wasn’t the settling of the West; it was the powerful urbanization and industrialization of the East. In 1860, the United States had thirty thousand miles of railroads and produced ten thousand tons of steel a year. By 1900, it had 200 000 miles of railroad and turned out six million tons of steel, overtaking Britain as the world’s top producer.

But a city schoolchild or factory wage slave still needed a mythical space for his or her dreams; and the Western appeared in pop culture to service this escapist need.

Its arrival coincided with America’s answer to Britain’s penny dreadfuls, the cheap and sensationalistic pamphlets we know as dime novels.

The term is generally agreed to have sprung up in 1860, in the title of Beadle’s Dime Novel series. The dime novel flourished circa 1860 to 1910, not becoming extinct until around 1925. Yet its decisive influence — both in content and in format — on popular fiction up to the present day merits a detailed overview; indeed, the comic book is the direct descendant of the dime novel, in more ways than one.

Post- Civil War America ushered in a golden age of magazine publishing. New printing technologies allowed enormous press runs and attractive graphics, often featuring color; railroad networks enabled, for the first time, real national distribution across the vastness of the republic. Literacy was universal (possibly higher than it is today.) A growing middle class had more money to spend on leisure, and the magazines stood ready to provide them fitting entertainment.

For the highbrow, Harper’s or the Atlantic provided choice literature; middle-class families enjoyed the weekly ‘storypaper’ anthologies that serialised romantic or historical novels, such as the New York Ledger. As for respectable young folk, they could turn to equally respectable children’s magazines — the Riverside Magazine for Young People or the St Nicholas’ Magazine, for instance.

But what of those deplorable young people who craved fare that wasn’t respectable?

The weekly dime novel offered its raffish lowbrow charms.

Some aspects of the dime novels point to the future– ultimately, to the adventure comic book, and hence to the superhero comic.

In contrast to the storypapers, which appealed to all members of the family, the dime novels quickly succumbed to market segmentation; and, though some of them were aimed at a feminine audience, and many adults read them, they were predominently catering to boys aged 9 to 16, mostly from the working class.

They appeared weekly, bi-weekly, or occasionally monthly, and were distributed on newsstands and in dry-goods and candy stores– the “mom and pop” mainstays of comic-book distribution until the 1970?s.

They featured, issue after issue, the death-defying adventures of the samecolorful heroes, often operating outside the law: this was the norm in the dime Westerns.

Upon closer acquaintance with Westerns as presented in dime novels, their differences from their twentieth-century equivalents are enlightening. Yes, we have battles with Indians and cattle rustlers; but the latter are more often than not mere spear-carriers for the real villains: the rich.

The outlaw hero is typically a young man of sterling character who has been dispossessed by scheming plutocrats, and forced into a Robin Hood life of high-minded crime. The law and its representatives– judges, sheriffs– are wholly corrupted by moneyed interests; the only recourse of our hero is to take the law into his hands.

Typical is the case of ‘Deadwood Dick‘, the popular creation of Edward L. Wheeler, first appearing in 1877. Young Edward Harris is swindled out of his inheritance by the Filmore brothers. As he explains:

I appealed to our neighbors and even the courts for protection, but my enemy was a man of great influence, and after many vain attempts, I found that I could not obtain a hearing; that nothing remained for me but to fight my own way; And I did fight it.

He becomes the masked highwayman Deadwood Dick, who, after many adventures, finally manages to capture the villainous Filmores. He serves them his own brand of justice:

Now, I am inclined to be merciful to only those who have been merciful to me…Boys, string ‘em up!

And his gang hangs the wealthy malefactors. The reader has been maneuvered into cheering on lynch law.

Thus, the populism of the dime Western has its darker side. Class resentment on the part of their proletarian readers leads to an exacerbation of individuality; the law is a plaything of the rich, and so to be discarded altogether; what remains is the revenge fantasy.

Revenge is a kind of wild justice, which the more man’s nature runs to the more ought law to weed it out — Sir Francis Bacon

Consider the following lynching by a self-described “mob of one”:

Lighting a fresh cigar, Dick watched the convulsions of the two men until they had ceased, his wild glances gradually becoming less wild, and by the time both forms had become motionless in death, his eyes had become as mild and gentle as those of a gazelle. His desire for vengeance had been appeased! His sense of duty and justice satisfied!’ — from Daredeath Dick, King of the Cowboys, by Leon Lewis

This is vigilantism, the privatisation of justice and of vengeance. It is an implicit premise of every crime-fighting superhero to this day.

(This glorification of outlaws also alarmed the establishment; dime novels extolling criminals such as Jesse James, the Daltons, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid made the fortunes of publishers Frank Tousey and Street & Smith, until, in 1903, public outrage and the threat of the Postmaster General to revoke second-class postal privileges caused the cancellation of all ‘true outlaw’ novels.

One may legitimately wonder whether the authorities were more alarmed by the praise of lawbreakers, or by the populist, subversive ideas that permeated these books.)

Vigilantism is known worldwide — see the Vehmgerichte of medieval Westphalia, or the White Hand death squads of modern Brazil — but it is seen, abroad, as a source of terror; in the U.S.A. alone is it romanticised.

This may partly be due to the necessity, in vast wild territories under little more than nominal control of government, of appealing to civilians to defend the country from attack, whether military or criminal. That necessity informs the second amendment to the United States Constitution:

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

The problems arose when militias were not “well regulated”. There were legal frameworks, most famously the law of “posse comitatus” enabling a sheriff to commandeer any able-bodied man in his jurisdiction for purposes of law enforcement: thus the “posses” galloping through Western movies.

A real-life 1922 posse in Arizona, with two captured murderers

But irregular vigilante groups abounded in real life: the San Francisco Committee of Vigilance, the Montana Vigilantes, the Bald Knobbers of Missouri all resorted to clandestine murder and other terror tactics against lawbreakers, generally to the applause of the populace and the fury of the authorities.

Small wonder the vigilante found himself cast as a hero of American pop literature, first in the dime novels, then in pulp magazines, and finally in the modern-day comic book. Deadwood Dick is a direct ancestor of the Punisher and other vigilante superheroes — which is to say, of nearly all of them.

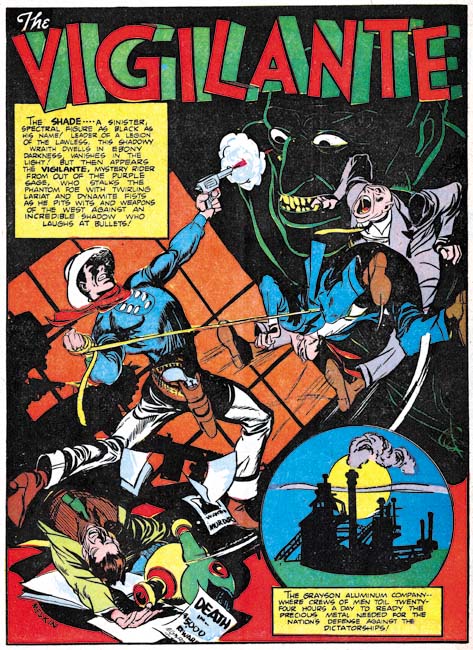

From Action Comics 43 (December 1941): art by Mort Meskin. As direct a link as can be between the old West and modern superhero vigilantes.

The United States of the dime novel’s heyday was undergoing immense upheavals. Gigantic corporations — the ‘trusts’ — came to dominate the economy: Armour, International Harvester, Standard Oil, United States Steel.The immense wealth of cattle barons and of what we now call ‘agri-business’ was choking the life out of traditional smallholding family farms and ranches. The modern Labor movement was coming into a painful and violent birth, against a backdrop of falling wages due to automation and mass immigration amid severe, recurring recessions.

And ironically, just as the Western reached the pinnacle of popularity, the Frontier had closed. As the historian Frederick Turner noted in The Frontier in American History (1920), this closing heightened ” the sharp contrast between the traditional idea of America — as the land of opportunity, the land of the self-made man, free from class distinctions, and from the power of wealth — and the existing America, so unlike the earlier ideal.”

Is it any wonder that powerless working-class adolescents should subscribe to dreams of summary justice dealt by outlaws to evil, moneyed malefactors? Or that this dream should linger into the twenty-first century?

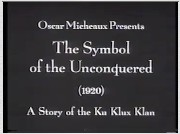

Let us end this chapter by taking note of one of the most vicious and evil vigilante organisations of all time: the Invisible Empire of the Ku Klux Klan.

The Klan was formed after the Civil War defeat of the southern Confederacy, in 1865, as a secret organisation bent on terrorising freed Black Americans and Republicans, as well as Catholics and Jews. Their ‘Masked Riders’ secretly murdered and tortured. A rump of this vile gang lives on today, still spreading its doctrine of hate.

The Klan had its spectacular — some would say ridiculous — side. At their meetings, or ‘klonclaves’, masked members ( with titles like Wizard, Dragon, Titan, or Fury) would burn crosses and chant slogans.

A masked Klansman before a burning cross

Let’s see… masked vigilantes with colorful names hiding their secret identity… sound familiar?

I think it’s inescapable to conclude that something uniquely American led to both the formation of the KKK, and the emergence in the U.S.A. of the superhero.

That’s right: the first major superhero film is D.W.Griffith‘s The Birth of a Nation (1915).

Next: Into the 20th Century– pulps, funnies and radio

————————————————————————————-