This is part of a roundtable on the work of Octavia Butler. The index to the roundtable is here.

__________

Most of the posts in the Octavia Butler roundtable (including my earlier post) have been fairly laudatory of Butler’s work. And there’s certainly a lot to like in Butler’s novels. She tackles complicated themes in imaginative ways and manages to be quite repulsive while doing so. Not many folks out there walk the line between slavery narratives and tentacle sex. Hard not to cheer for that.

But, while I like Butler quite a bit, I do have some reservations. The main one being that she’s not a very good writer.

Of course, Butler is a good writer in some ways. As I said, she’s very inventive and thoughtful; she has lots of ideas; and she explores them in interesting ways. Still, reading her, you can’t help but notice that her prose rides a fine line between uninteresting and actively insipid. Yes, there’s tentacle sex, but it’s tentacle sex described with all the fever and poetry of a long, leisurely session at your tax accountant’s. Mutant eternal killer demons speak from out the ages with the somnolent laconic lack of affect of a Calvin Coolidge. Apocalypses of multivariant forms all land upon an unsuspecting earth like wire service news bulletins. Characters of diverse class, race, and ethnicity, whether blood-sucking vampires or gelatinous fern assemblages, all speak with a default mid-range vocabulary, eschewing figurative language for bland glops of transparent earnestness.

Here, for example, is Mary, a troubled young African-American girl who is coming into her own as a massively powered telepath who can read the minds of hundreds and hundreds of other psis all bound to her will. She has just defeated her only rival for power. It’s an emotional moment. Right?

Not so much.

They cremated Doro’s last body before I was able to get out of bed. I was in bed for two days. A lot of others were there even longer. The few who were on their feet ran things with the help of the mute servants. One hundred and fifty-four Patternists never got up again at all. They were my weakest, those least able to take the strain I put on them. They died because it took me too long to learn how to kill Doro. By the time Doro was dead and I began to try to give back the strength I had taken from my people, the 154 were already dead.

he sentences sit there in a Hemingwayesque funk, desperately hoping that the short. simple. structure. will lead you to think that the passage is economical, even though she keeps repeating the same not especially revelatory information with a distant, feeble ruthlessness. They were the weakest, and they could not take the strain; they were dead, and then they were dead, and at the end of another sentence, they’re still dead.

Perhaps you could argue that Butler is deliberately using a simple voice to convey Mary’s consciousness here — but, again, Mary is supposed to at this point be an incredible mutant superconsiousness. What is it like to be inside the head of someone who is inside the head of hundreds of other people? How must it feel to know all those other people’s lives and vocabularies? If Samuel Delany or Gwyneth Jones or Joanna Russ or any number of Butler’s compatriots in the realm of gender-bending avant sci-fi art were writing this, Mary’s consciousness would be multi-vocal and strange — it would mirror alienness in its syntax and grammar and language. Mary wouldn’t just say, “Hey! I’m different! How about that?” Her voice would be part of the meaning of the novel. But it’s not, because it can’t be, because Butler has no interest at all in language, the supposed tool of her trade.

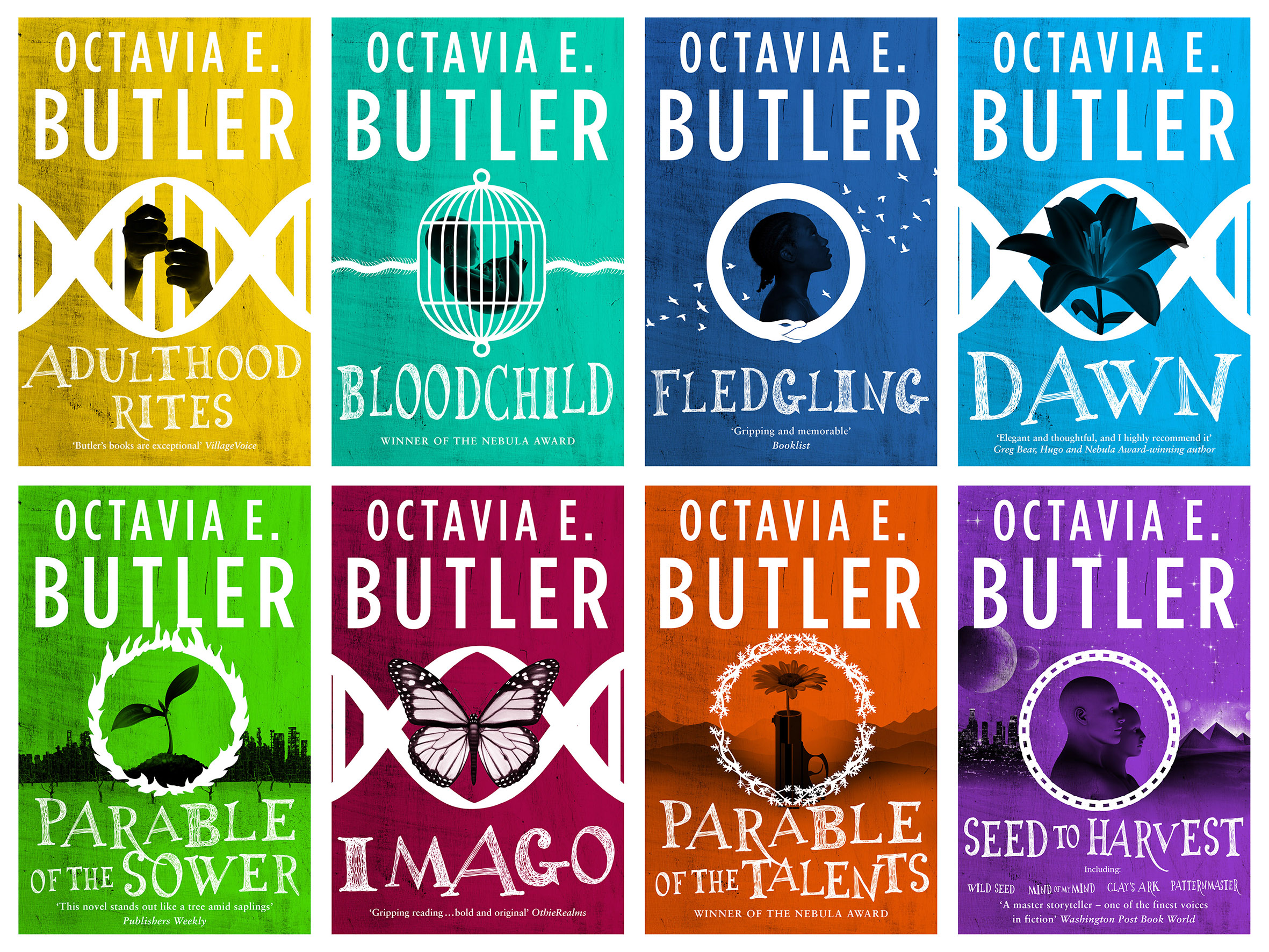

There are times when the lax limpidity of the prose does work thematically, at least up to a point. “Dawn” and “Fledgling” can both be read as coming-of-age novels, with the protagonists growing up to discover their true selves as tentacled imperialist monstrosities and vampiric incestuous slaveholders, respectively. In these books, you could argue, the flatness of the prose (and as a result of the affect) has an almost satirical fillip; the default of bland genre becomes a patina of normalcy over a pit of perversion and alienness. The nice, easy story isn’t so nice and easy — or possibly vice versa.

Still, it seems pretty clear that, in many respects, better prose would in fact result in better books. In “Wild Seed” and especially in the earlier “Mind of My Mind”, Butler creates careful moral dilemmas, only to have them sag beneath the damp uselessness of her style. Doro, the eternal mutant who survives by jumping from body to body and killing his hosts, is, as I’ve said, completely unconvincing; when he speaks he sounds not like an all-powerful parasite, but like mid-range science-fiction narrator explicating.

Even worse is the fact that the rest of the characters are equally indistinguishable and bland. Doro is supposed to be a monster, destroying person after person — but the people he destroys aren’t real. We never feel any deaths, because the characters are just chits Butler moves around the page. It’s almost as if Butler is Doro; he sees humans mostly as personality-less puppets to manipulate through his plots, and Butler treats the humans as personality-less puppets to manipulate through her plots.

This is especially painful in “Mind of My Mind” where Butler switches point of view characters repeatedly, in an effort (presumably) to have us get to know each one. But instead, what we get to know is that they’re all the same. In theory, if we actually could tell one from the other, we might feel some sort of loss when Mary pulls them into her pattern, and they abandon their independence. But it never happens, because they were never individuals to begin with. Similarly, the Patternists take over the minds of normal humans (mutes) and enslave them. But it’s hard to much care when the humans are blandly uninteresting before being slaves, and then blandly uninteresting afterwards. How can you provide a moral meditation on human individuality when you’re unable to create an even passable representation of an individual human?

In her post on Butler and empathy, Qiana Whitted says that she is impressed with the way that Butler creates repulsive insect-like aliens as a barrier to empathy. It’s true that Butler’s aliens can be squicky, and that can in some cases be a way to withhold empathy, or insist on difference. But those insisted-on differences in Butler’s work rarely go more than squick-deep. Bodies in Butler may be wildly heterogenous and imaginative, but her language is always the same untrammeled non-thing, scooping up tentacle creature and vampire alike in its unwavering similitude. Everybody thinks alike and talks alike, which means that on the level of the prose, which is the essence of the book, Butler often seems unable to think difference at all. Maybe that’s why her books can seem oppressive — not because she has a bleak vision of human intolerance for strangeness, but because the pattern in her books is too flat to allow the strangers called humans any life of their own.