Reprinted from text scans of The Comics Journal #234 (June 2001)

History appears to indicate that William Hope Hodgson was not a particularly lucky individual. Rejected hundreds of times during the course of his literary career and finally blown to bits in Belgium towards the close of World War I, he could not have hoped for more in death. As such, he has largely been forgotten: his books have long gone out of print and even his finest works have been edited to eliminate excessive sentimentality by his literary supporters. Poor precedents indeed for Richard Corben and Simon Revelstroke’s pioneering adaptation of one of his works.

Born in Essex, England, into a family with an Anglican clergyman at its head, it has oft been pointed out that Hodgson’s family was frequently transferred to various removed locations including that of Galway in Ireland where The House on the Borderland (1908) is set. At various times in his life a sailor, a body builder, a photographer and an author, Hodgson’s works include The Boats of the Glen Carrig (1907), Carnacki, The Ghostfinder (1913, originally published as short stories in various magazines), and The Night Land (1912).

That tower of the horror genre and bane of elitists everywhere, H. P. Lovecraft, is frequently quoted (in cover blurbs) in defense and praise of Hodgson’s most fatuous book. He called it “a classic of the first water” and “perhaps the greatest of all Mr. Hodgson’s works.” Further, with regard to its place in literary history, he considered the “wandering of the narrator’s spirit through limitless light-years of cosmic space and kalpas of eternity . . . something almost unique in standard literature.” Others, such as Clark Ashton Smith and C.S. Lewis, have followed suit with praise for the imaginative elements found in Hodgson’s other novels.

Reason enough, one might think, for an adapter to create an unsullied version of this seminal work. To no avail. On the contrary, Corben and Revelstroke have chosen to adapt Hodgson’s novel in a way that makes the editor’s decision to label such changes “an original framing sequence that taps a contemporary vein” nothing short of diabolically disingenuous.

Here are the facts of the novel which do remain intact. While on a trip to West Ireland, Messrs. Tonnison and Berreggnog discover a manuscript detailing the final days in the life of a recluse and his sister, Mary, in a large house with a reputation among the local villagers of having been built by the devil. Almost from the outset, the narrator is plagued by feverish dream-like states compelling him to drift in disembodied fashion to arcane locales, sometimes encountering dangers in the form of swine-like creatures and at other times traveling through the millennia to witness apocalyptic visions of the end of life on earth itself. And that’s about it. Apart from these bare facts, very little else remains intact.

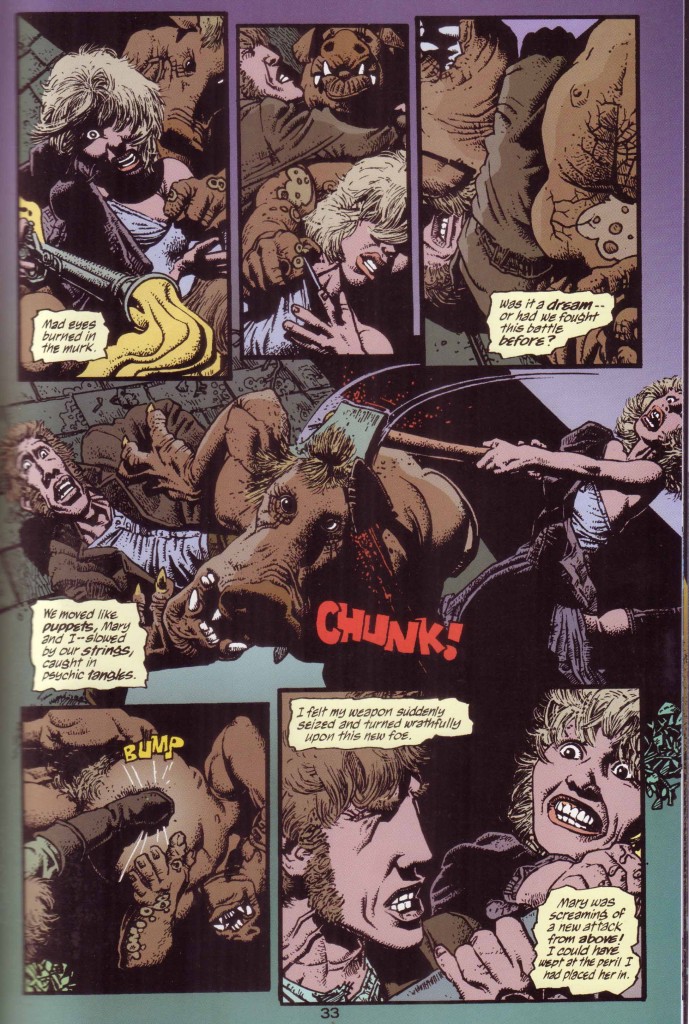

Some of Corben and Revelstroke’s changes are easily explained, though perhaps not as easily countenanced—their substitution of the original narrator’s almost placid defense of his house and sister against the swine creatures with a 20-page hammer and tongs affair involving a slew of blunt weapons and firearms, for instance. The former account is suspenseful and full of pent up energy while the latter simply revels in violence, not an unfamiliar predilection in Corben’s other works.

Less explicable is the authors’ decision to slice off thc entire first section of Hodgson’s manuscript which sees the protagonist floating across a plain of desolate loneliness into a valley of murderous gods in half-slumber. Hodgson’s writing here is energetic and effective and the protagonist’s first encounter with the swine creatures in this section of the book, a most useful cap to the almost signature dreamscapes he creates. One can only guess at the reasons why such a key sequence was excised. It does allow for delay in the introduction of the swine creatures which grow to dominate the book and it might have been felt that the portrayal of such unearthly elements so early on would not have served the rhythmic crescendos of the comic. Yet these are sorry excuses for such vandalism.

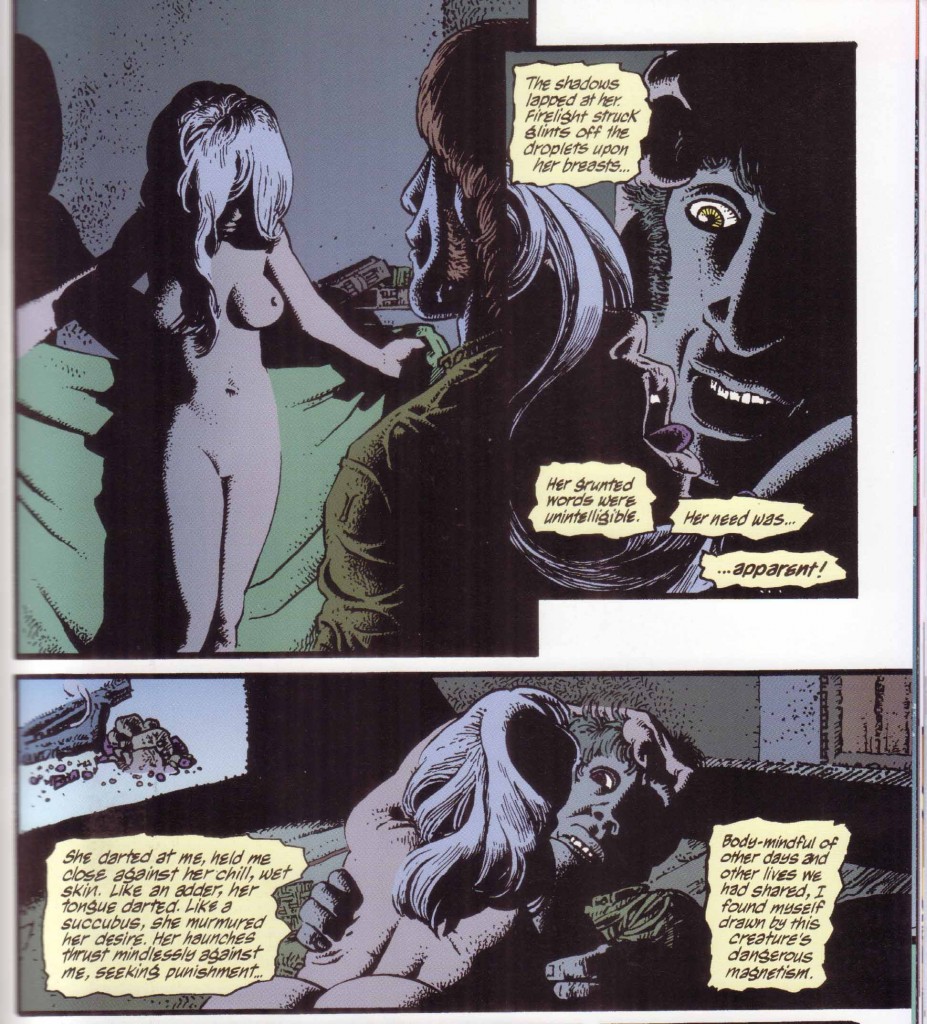

Equally dissatisfying is the comic’s tendency toward logic and cozy explanations, features with no place in Hodgson’s novel, which revels in its utter obscurity, failing at every turn to apprise the reader of its true meaning. As it happens, the comic comes close to a complete rewriting of the text stopping only to preserve some of the main points of the novel, while adding elements with a rampant disregard for its sexually innocent strains. In relation to this point and as their centerpiece, the authors present us with a mildly perverted 20th century interpretation of Hodgson’s work: the swine beasts who hardly even touch Mary in the original, are now doing the needful and have procured an “intent which is hideously clear” (the panel in question shows Mary two legs thrust in the air and spread wide in deference to those readers who have not divined this clarity.)

These elements do not reside in Hodgson’s book but are a kind of freeform interpolation on the part of the adapters, taking the mysterious seclusion of the siblings and extrapolating this to its ultimate late 20th century conclusion. I can only surmise that they felt free to do so since any thinking reader glancing through Revelstroke and Corben’s adaptation would realize that Hodgson would probably have been pilloried and sent to Reading Gaol if he had undertaken such an offensive stance.

These sexual shenanigans may have their origins in some of the vague plotting Hodgson resorts to two thirds through his novel. Here he introduces the hitherto unknown aspect of the protagonist’s former fiancee. Hodgson’s protagonist writes in an elliptical way about his former love and his sister’s increasing withdrawal and distance from himself, almost as if she were possessed of greater apprehensions about her own brother than the swine creatures lurking outside the house. These enigmatic relationships are twisted into a secret lust for his own sister in the adaptation; the swine creatures now symbolic of the protagonist’s own fears.

The creatures take on the role of his sister’s manhandlers and rapists, opening her up (by means of a feral bite) to the carnal delights of incest. Later in the comic, she strips brazenly for him and caresses him in a most vile yet delectable manner. These sexual feats bring Mary to the forefront of a story in which she is curiously absent — and in which she was certainly not the deranged, gun-toting, buxom Rambette of the comic.

It might be best to see the comic not as an adaptation in the purest sense of the word but a combination of adaptation and homage comparable to the wealth of fan and professional fiction that has sprouted up around the Cthulhu Mythos (and to a considerably lesser extent the prose-form House on the Borderland). Nowhere is this better seen than in the final section of the book where there are musings on the nature of fear, wherein the author of the manuscript becomes a makeshift replacement for Hodgson himself speaking of the “Outer Dark,” “Watcher[s]” (references to Hodgson’s The Night Land) and the guarding of portals between unknown nightmarish lands and our own.

It is interpretive in a way that echoes Alan Moore’s musing upon the source of the novel’s magical qualities in his introduction to the comic adaptation: the Jungian landscape of the house and the porcine quality of the men Hodgson may have come across in his travels during his youth. The borderland is seen as a place between “waking thought and the night-land of the unconscious.” In this sense, Corben and Revelstroke’s idea of the shifting nature of the house, at once a gateway, an asylum, and a state of mind, is not without justification.

It is also possible to surmise that the adapters have combined the ideas found in Hodgson’s short story, “The Hog” (a story from the Carnacki, The Ghost Finder cycle of stories), with those in The House on the Borderland producing a fusion of forms. Various themes in the adaptation may be seen to have their genesis in concepts articulated by Hodgson in “The Hog.”: the notion of being transformed into something less than human by contact with the swine beasts; the heightened terror of the protagonist in the basement cellar of the house (which mirror those of the hapless Bastion and the pit); the concept of the Hog as a “cloud of nebulosity,” an “Outer Monster” residing in an outer psychic circle—these ideas do not have as firm a basis in the original novel as they do in Hodgson’s short story. It will also be evident to readers of Hodgson that the explanations foisted on the strange events in the comic are more in keeping with “The Hog,” in particular the motif of unearthly intrusions and the ravenous feeding of those alien creatures on the fears of mankind. This may be compared with Carnacki’s thoughts towards the close of Hodgson’s short story:

“They plunder and destroy to satisfy lusts and hungers as other forms of existence plunder and destroy to satisfy their lusts and hungers. And the desires of these monsters is chiefly, if not always, for the psychic entity of the human.”

Clearly the adapters have taken the author of Borderland at his word, for Hodgson himself exhorts his readers to uncover the “inner story” according to personal “ability and desire.”

Of course, horror and science-fiction adaptations of this ilk are nothing new to Corben. There is the reasonably faithful adaptation of Harlan Ellison’s “A Boy and His Dog” in Vic and Blood for example. More relevant is Corben’s reworking of The Fall of the House of Usher, which demonstrates many of the idiosyncrasies which mar the comic Borderland: the bosomy lady phantoms; Madeline Usher traipsing about half-naked; and the fervid sex betwixt Lady Usher and Poe. The current adaptation of The House on the Borderland seems almost restrained by comparison. If anything, middle-age, Revelstroke and perhaps the sheer “respectability” of the Vertigo line have resulted in some of the reining in we find in the new work.

There is no doubt that the hard money at Vertigo has done wonders for the reproduction of Corben’s artwork. The slightly muddy printing of some of the Fantagor color books have been replaced by sharp, clear reproductions. What is missing and has been missing since the late 1980s has been Corben’s beautiful palette, which has been historically varied, rich, and at times subtle. The color work which Corben produced in the early 1980s and which probably reached its final flowering in some sections of his Children of Fire series has been described by the artist as “time consuming” and “highly evolved,” words which have no place in an age of quick fixes. Corben commented on his difficulties in an interview with Heavy Metal magazine in 1997:

“My style, although I have several styles, I used to do a fully-rendered, in-color style, but everything has to be done too fast now, so I’m doing a line style and then it is colored in. My attitude is different. When I started doing comics, I did them because I wanted to and if I made money, that was good. If I didn’t, well, I did them anyway. Now, I feel like I have to meet a financial quota.”

I mention this not as a criticism of Corben but of an industry which virtually compels its best artists to produce less than their finest efforts if they are to find a reasonable living within the industry. Even so, it must be said that The House on the Borderland represents something of a high point in Corben’s art. It also demonstrates that he is still holding firmly to many of the old values of naked big-breasted ladies, balding men, and free-wheeling literary license. It is, in the final analysis, entertaining and remains a good if not wholly truthful advertisement for Hodgson’s famous novel.