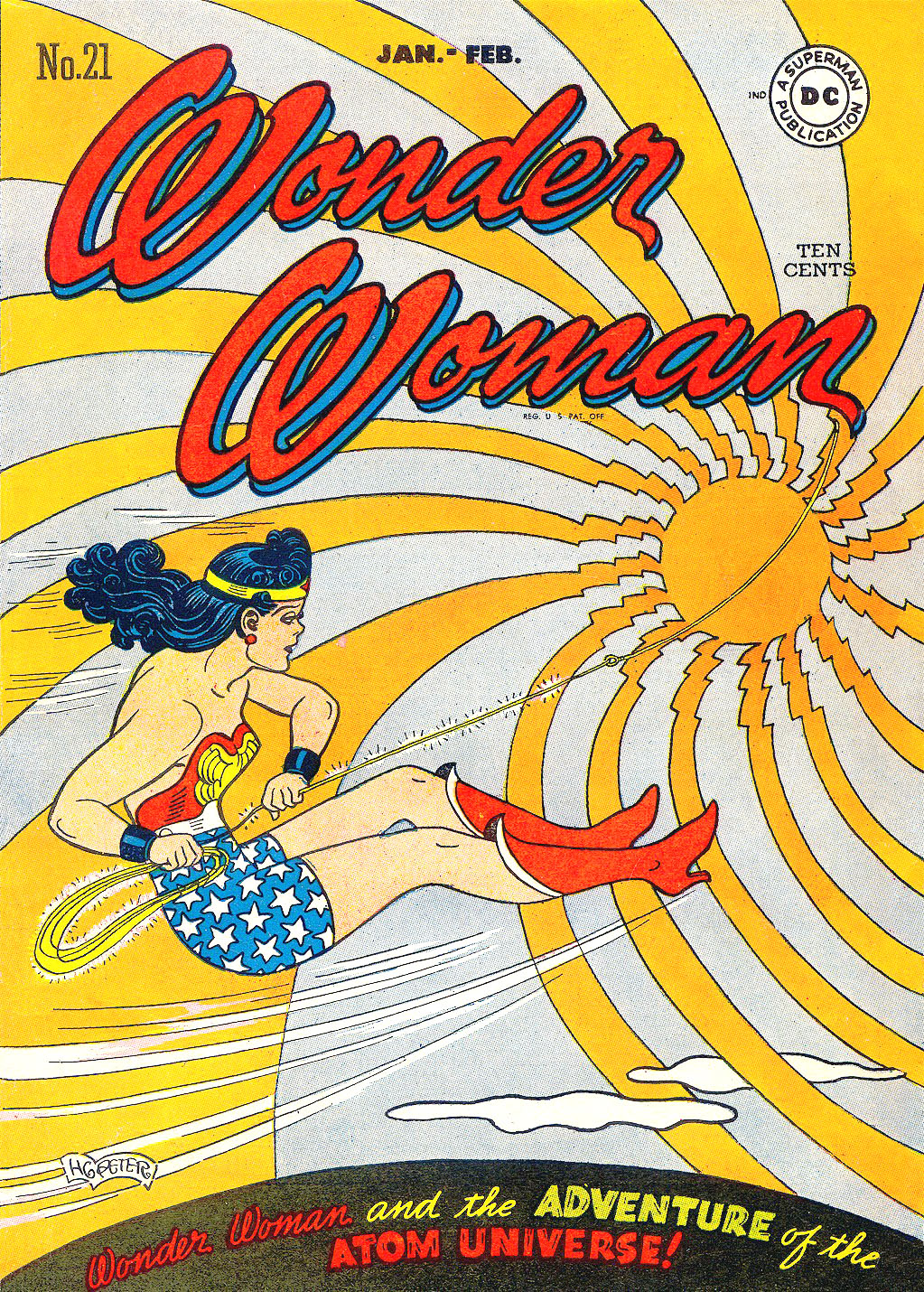

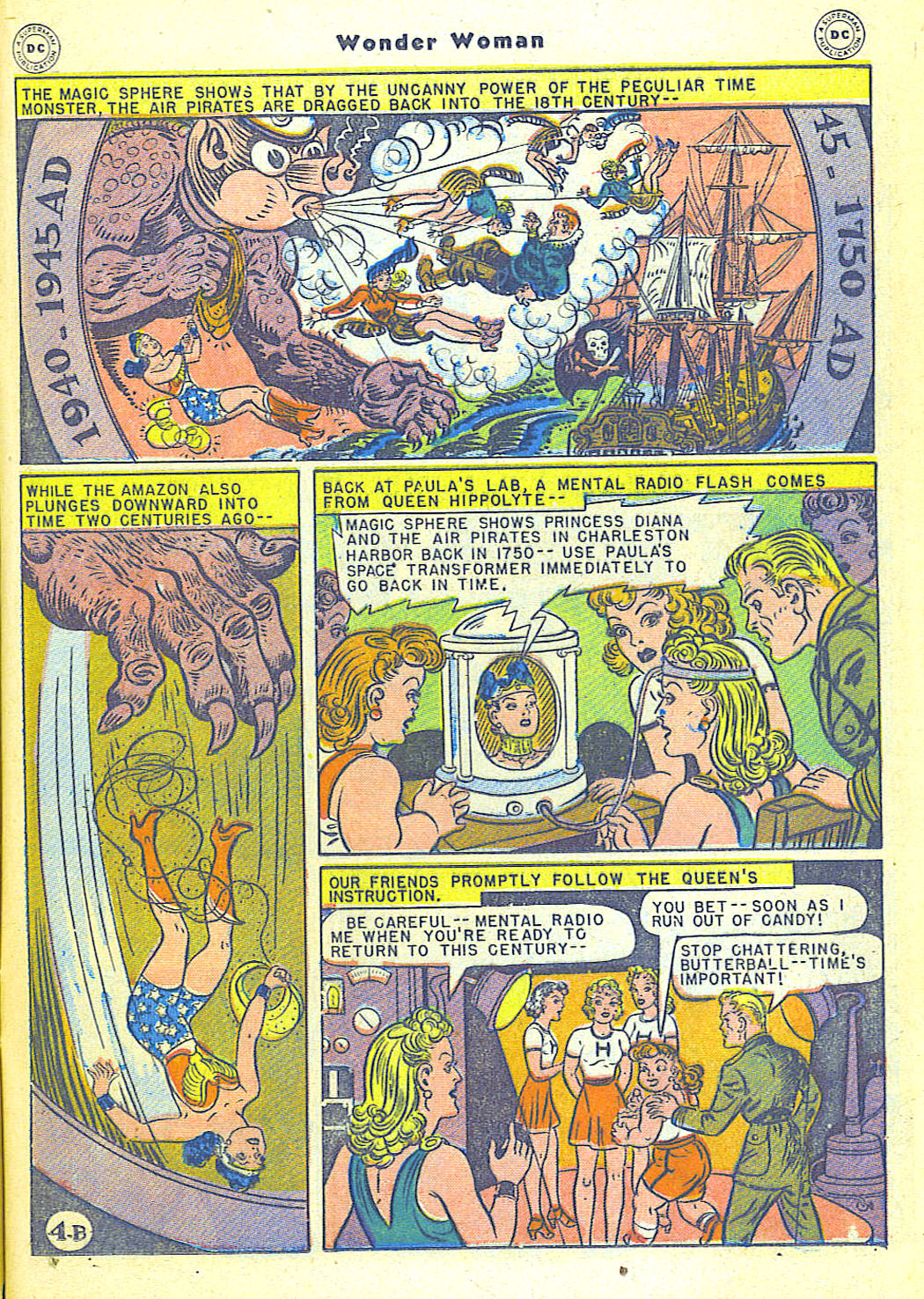

We’re up to #21 of the Marston/Peter run on Wonder Woman. The last few have been not so hot, and I have to admit that I’ve had a moment or two of doubt. After all, this is January/February 1947 here; when it was published Marston, who died of cancer in May, had only a couple of months to live. So…it seemed reasonable to wonder if maybe he hadn’t lost the spark, the edge, the compulsive and not at all unchaste desire to watch bound and blindfolded women perform surprising acrobatics with their teeth. Maybe the best was over.

I needn’t have worried. #21 is — well, let’s let it speak for itself.

And Grant Morrison thinks he’s weird.

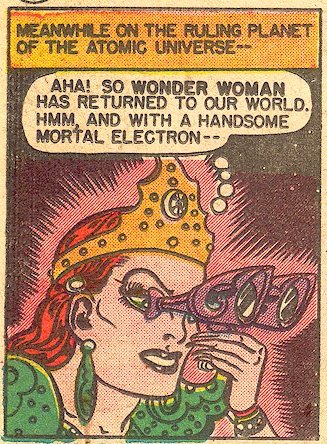

So, yes, as you may have guessed, this issue is, in post-Hiroshima mode, all about the perils and possibilities of atomic energy. Only, you know, it’s Marston, so the perils aren’t oh-my-god-the-bomb-will-fall-on-us-and-incinerate-us-to-death. Instead, the fear is that an evil matriarch ruling over a mixed community of females and robots on the surface of an atom may find a way to conquer the world!

Not very probable, you say? Well sure. But…look! Pretty colors!

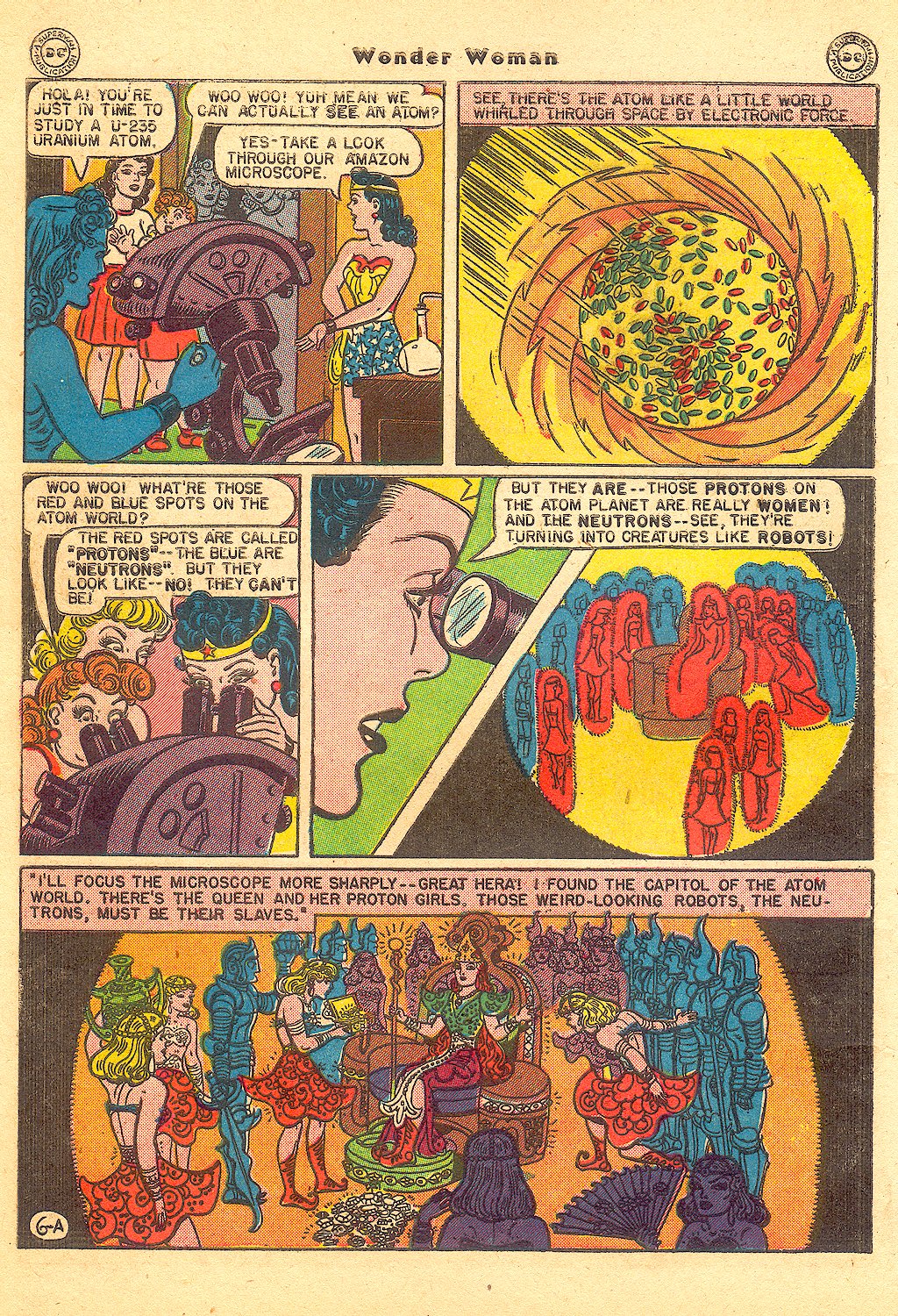

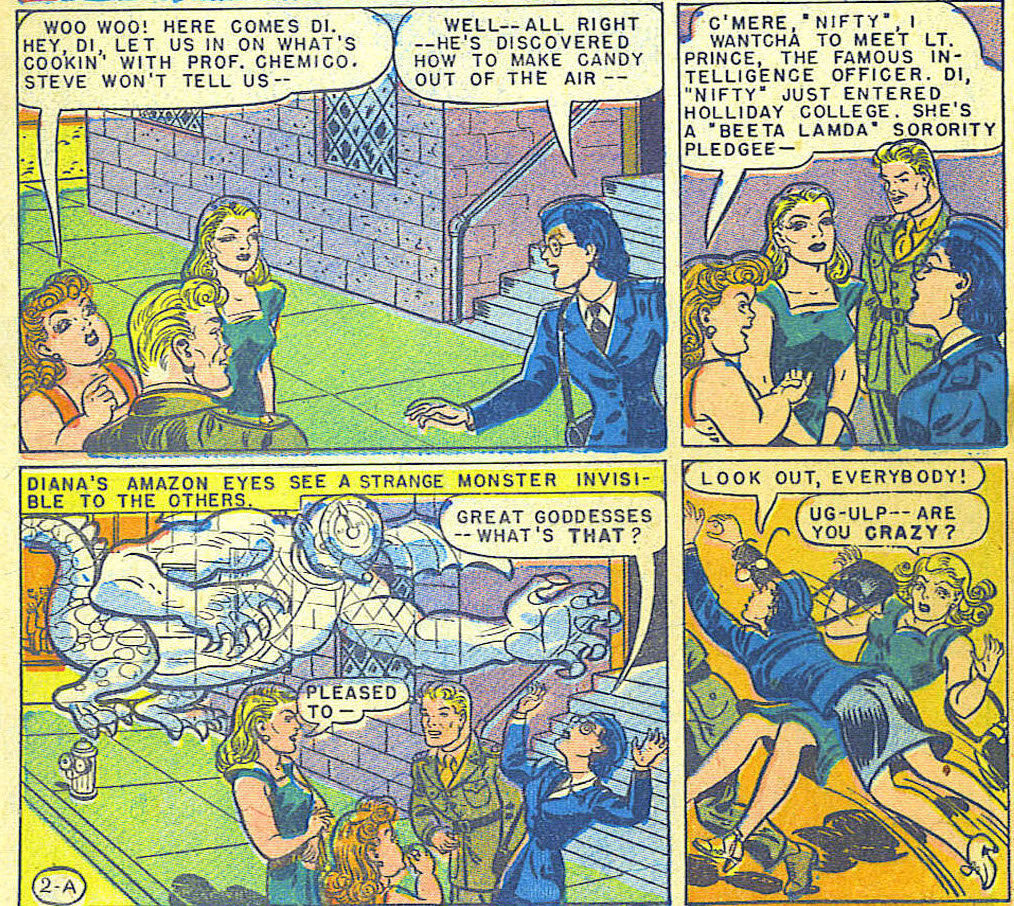

This is a lovely meta-moment from early in the comic; Wonder Woman and the Holiday girls are looking at a Uranium atom through an Amazon microscope. At first, they see just random bits of clumpy, sciency-looking stuff — inert, not human, and not especially Marston. But as they stare, the atom takes on more familiar characteristics. The protons look like red women, and the neutrons are “turning into creatures like robots!” That is, the way WW phrases it, it’s not just that she is able to see better or focus more clearly; rather, the atom is actually transforming before her eyes. It’s like the microscope looks into Marston’s brain, where the idea of atomic power lodged and, after a bit of a struggle, got transmuted by the alchemy of fetish into something closer to his usual concerns.

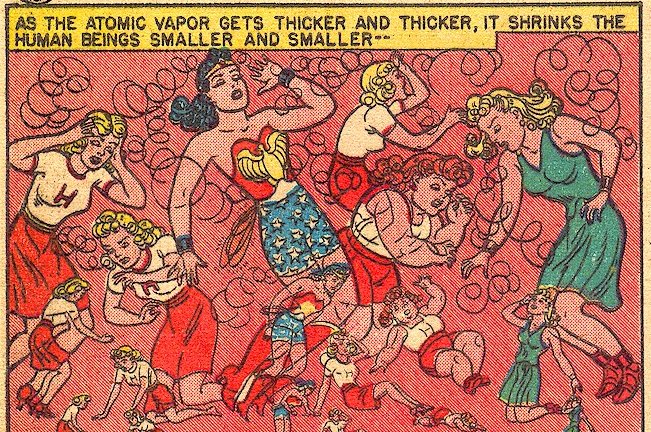

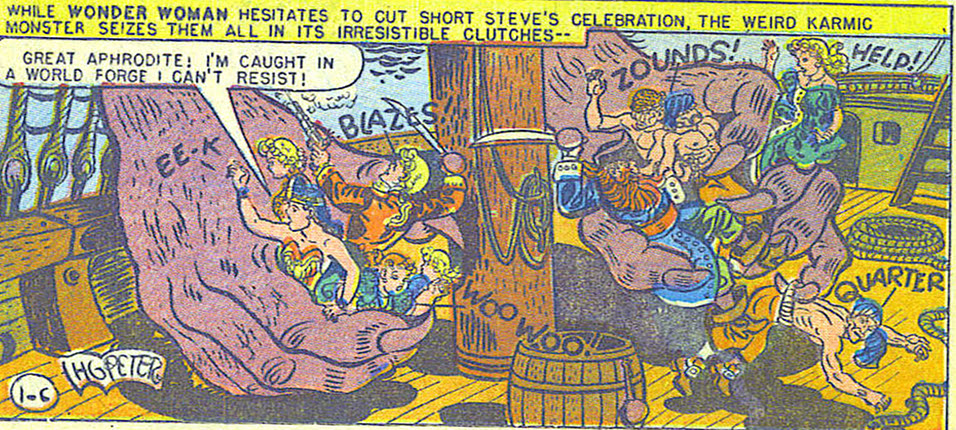

This is an amazing panel:

WW and the Holiday Girls are being shrunk down to the atom planet here…but the stiff stylization, the solid red background, and those awesome Harry Peter curlicue scribbles all make it look more like they’re being turned into wallpaper…or maybe dolls.

The way Marston links scientific miniaturization (atoms, protons, neutrons) to a feminized miniaturization (dolls, dainty frills) is brilliant, I think — it’s fascinating to see him incorporate cutting edge pop science into his preexisting edifice of crankery. But beyond that…well, thinking about this comparison has led me to realize the extent to which Peter, throughout WW, looks like he’s drawing, not people, but dolls.

The contrast between the stiffness of the figures in that upper left panel and the frilly, poofy expressiveness of the dresses — they look like porcelain figures.

I mentioned Sharon Marcus’ Between Women: Friendship, Desire, and Marriage in Victorian England last week. Anyway, in the book, Marcus devotes a great deal of space to talking about women’s relationship with their (female) dolls. She talks especially about “doll tales,” a genre of stories about girls acquiring, loving, and often abusing and leaving their dolls. Or as Marcus puts it:

Children’s literature tendered stories of imperious girls punishing, desiring, adoring, and displaying dolls that resembled fashionable adult women. In Victorian children’s literature, dolls are…beautifully dressed objects to admire or humiliate, simulacra of femininity that inspire fantasies of omnipotence and subjection…..Vicotrians did not confine objectification, domination and idealization of women to men. The stories they told about girls and their dolls show that Victorians imagined girls…enmeshed in indealizing and aggressive homoerotic fantasies.

You can see Marston having to stop at that point in order to fan himself vigorously.

Marcus argues that this kind of cultivation of homoerotic fantasy was not, in the Victorian context, lesbian. Victorians didn’t draw the strong lines between heterosexual and homosexual that we do…as a result, women desiring women or fantastizing about women didn’t necessarily make one less heterosexual. In fact, Marcus argues, the cultivation of homoerotic fantasy (through fashion plates or doll tales or through romantic female friendships) was seen as an important part of heterosexual female identity. Marcus notes, for example, that girls who treated their dolls well were supposed to make better wives; the cultivation of a partially maternal, but also potentially sisterly, bond, was indicative of one’s general capacity for love and care.

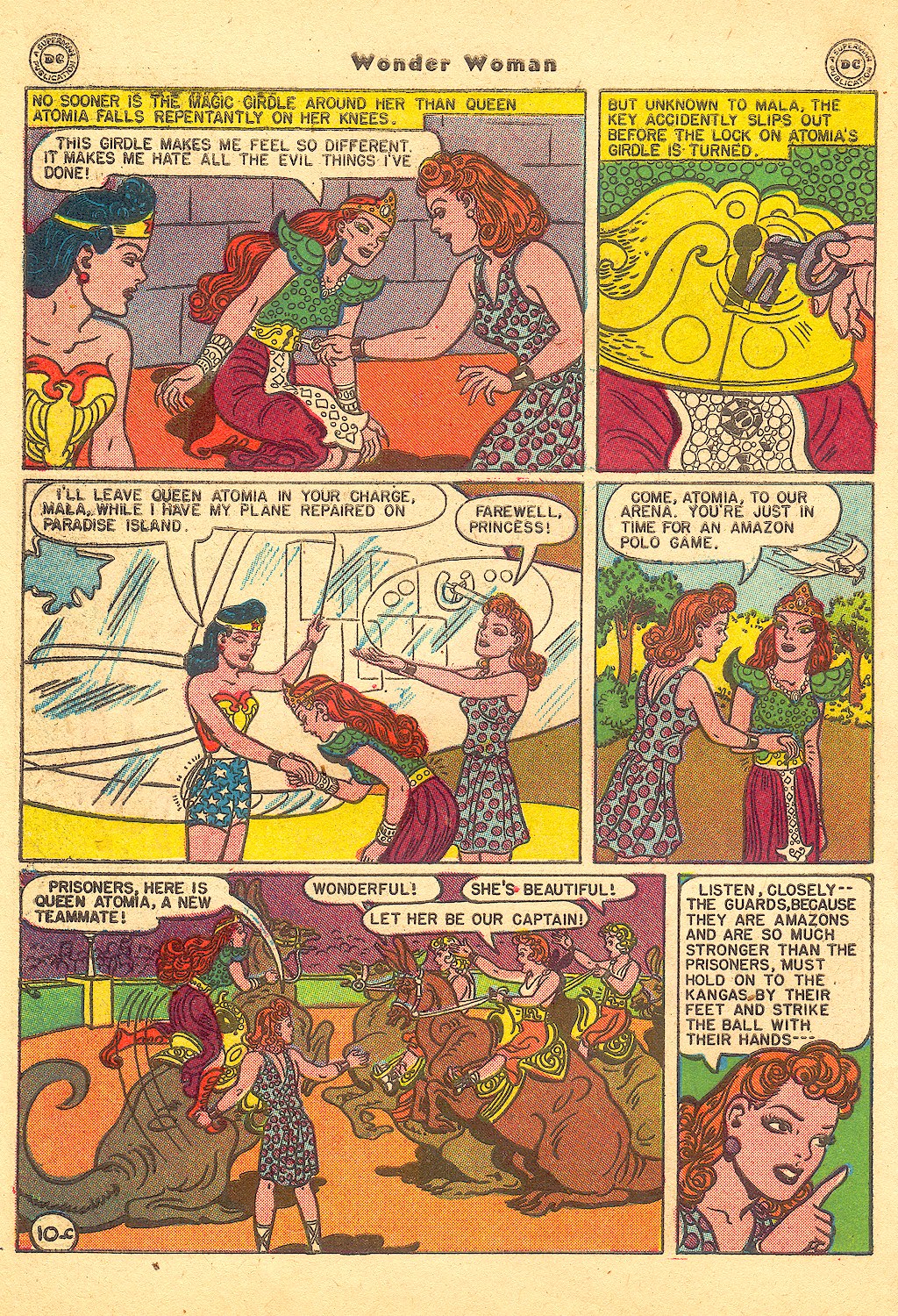

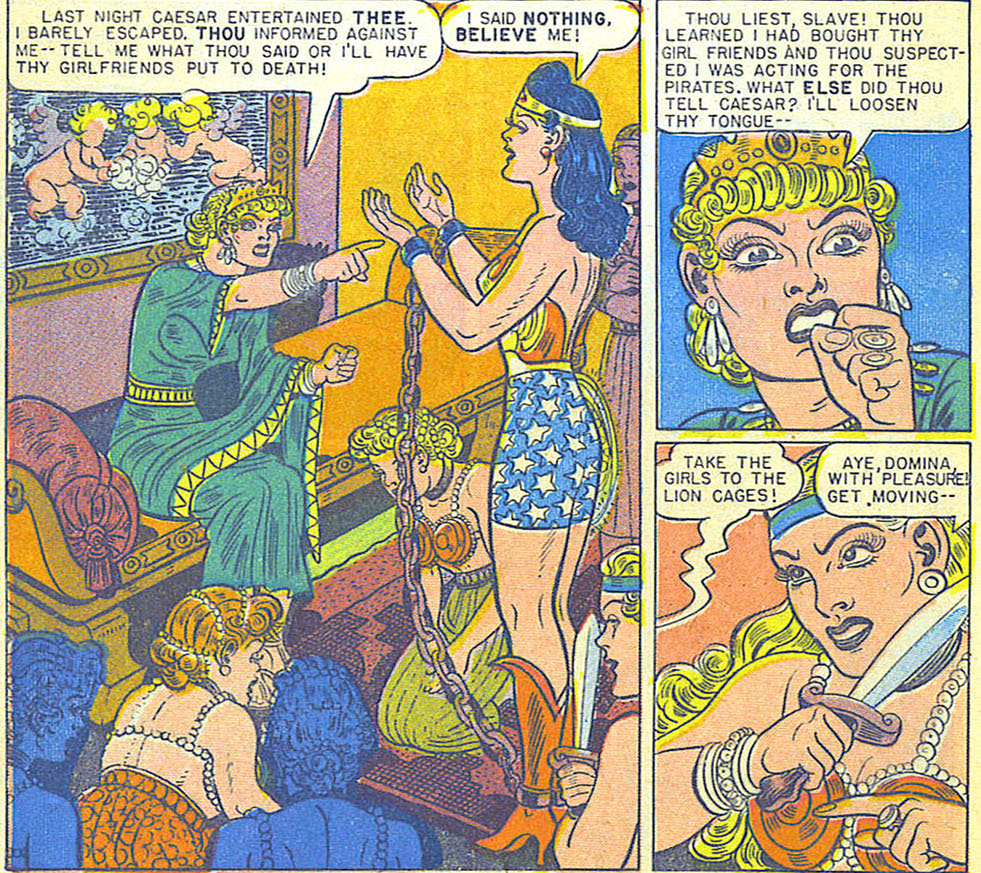

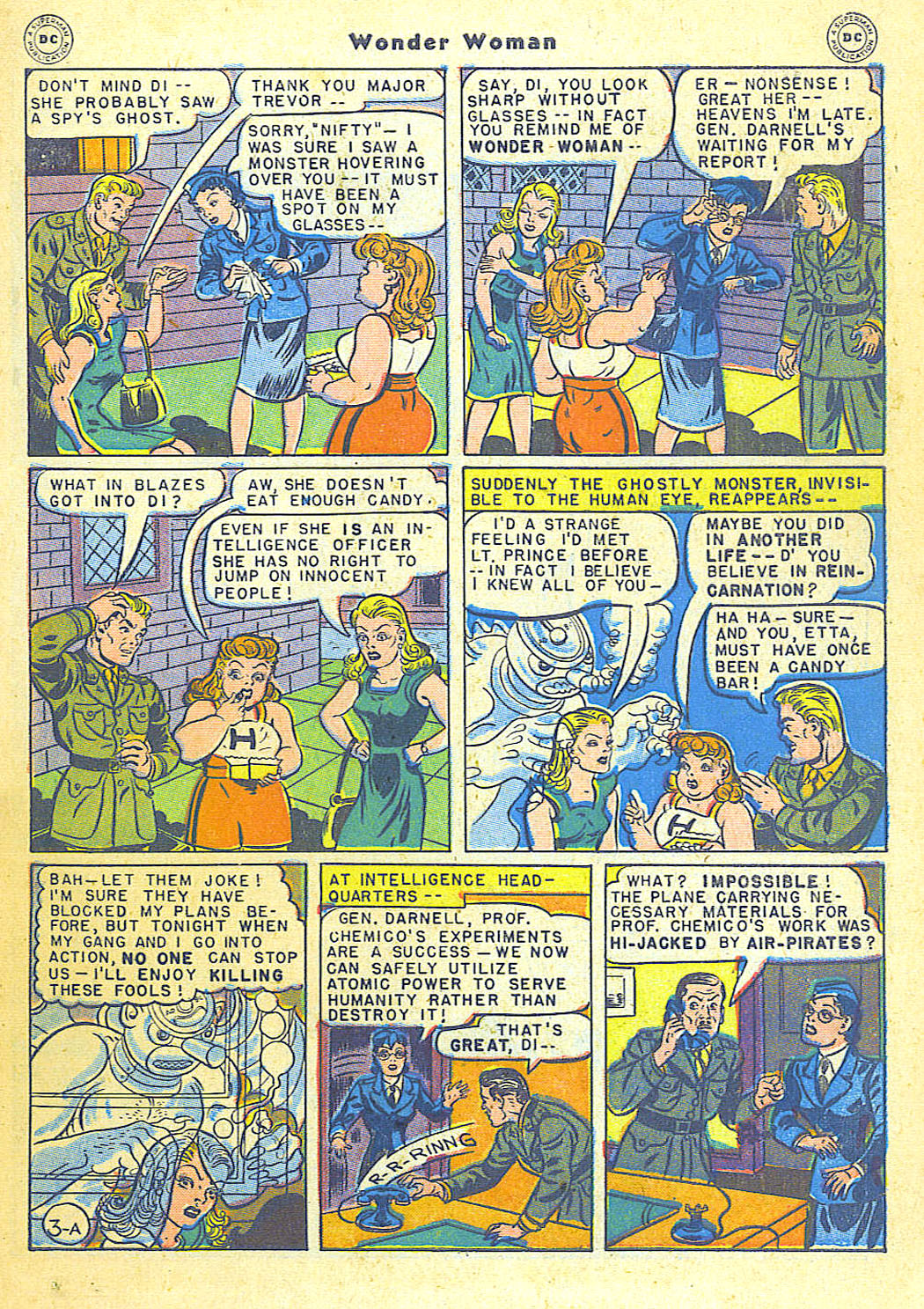

Since Marston lived with two female bisexual lovers, it seems, shall we say, unlikely that he didn’t see homoerotic fantasy in a potentially lesbian context. Still, I think Marcus’ take on doll tales gives a context for Marston’s particular interests. For instance, look at these pages again:

It’s not so hard to imagine the queen here as the little girl in a doll tale, abusing her dolls, commanding them about, gloating over their beauty (“pretty protons”!) and anticipating with relish a the continuing and ever-more-restrictive action of her own will. As in a doll tale, or in doll ownership, the female reader (or doll owner) is called upon to appreciate, manipulate, and sadistically control an icon of femininity. On the one hand, as Marcus notes this gives her a freedom of action to experience what are usually considered masculine pleasures — pleasures which would in most (Victorian and later) venues be denied her. On the other hand, (and here Marcus is suggestive but less clear) the sadistic inhabitation of femininity is a kind of practice. Linda Williams in Hard Core argues that the point of much pornography is to uncover or expose women’s inner self — that it’s primary impulse is a drive for total (sadistic) knowledge and occupation — an eradication of female self and replacement with male will or fantasy. Doll play, then, might be seen similarly as a drive to sadistically penetrate to the core of femininity — to pleasurably occupy it not in order to replace it with male will, but rather to settle down inside it as a grown woman.

What’s great about Marston is that he takes this already-queer woman-on-woman eroticized pedagogy and fetishistically flips all the genders. It’s not just boys who get to inhabit the feminine and so assert masculine power and mastery — girls can do the same.

Here the Queen is strapped into a Venus Girdle, making her loving and peaceful and generally the soul of femininity. And as soon as that happens she can go off and….participate in violent deeds of daring sport atop giant kangaroos!

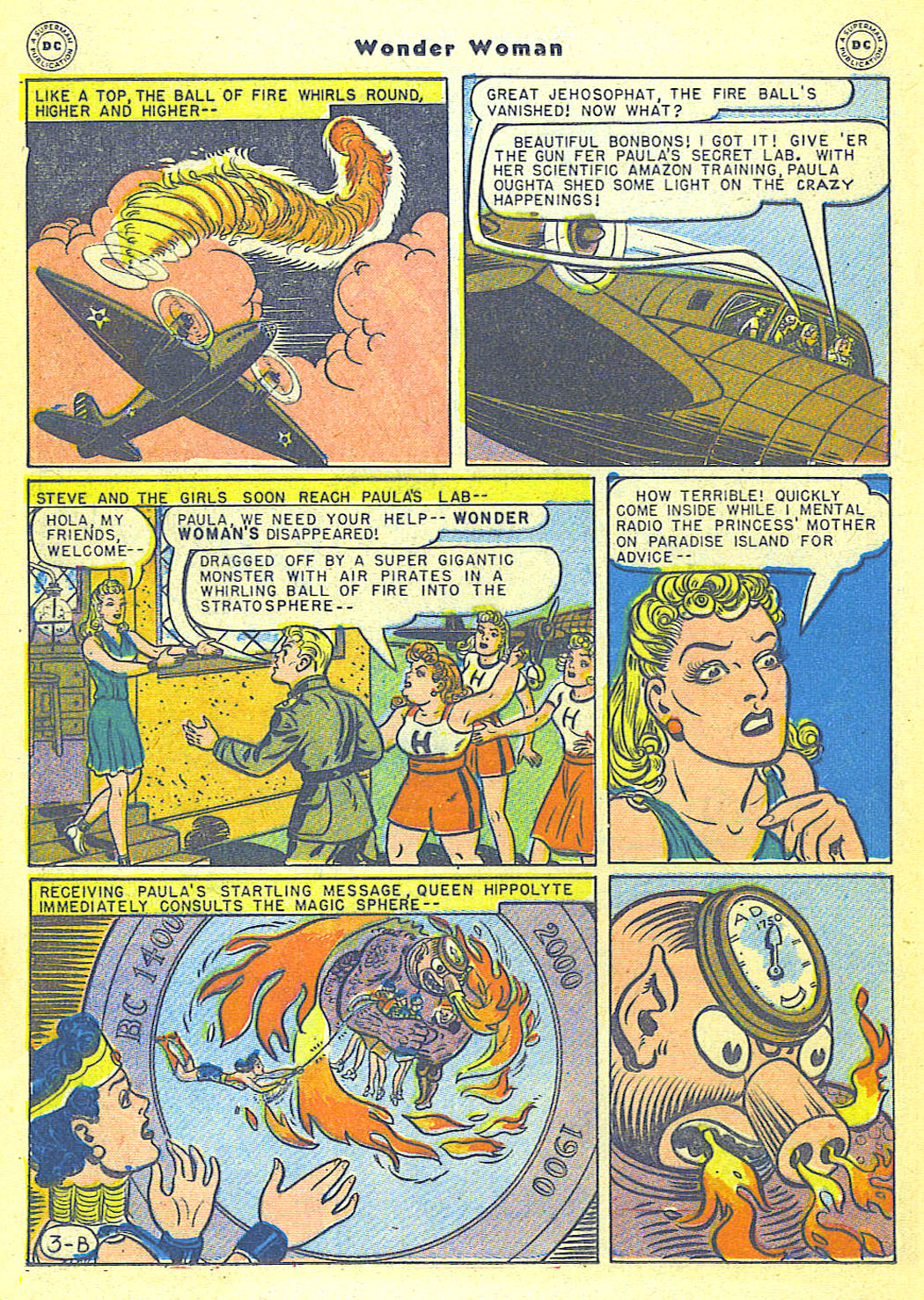

By the same token, it’s not just girls who sadistically inhabit the feminine in order to become mature women — rather, boys also get to manipulate the feminine in order to become mature women.

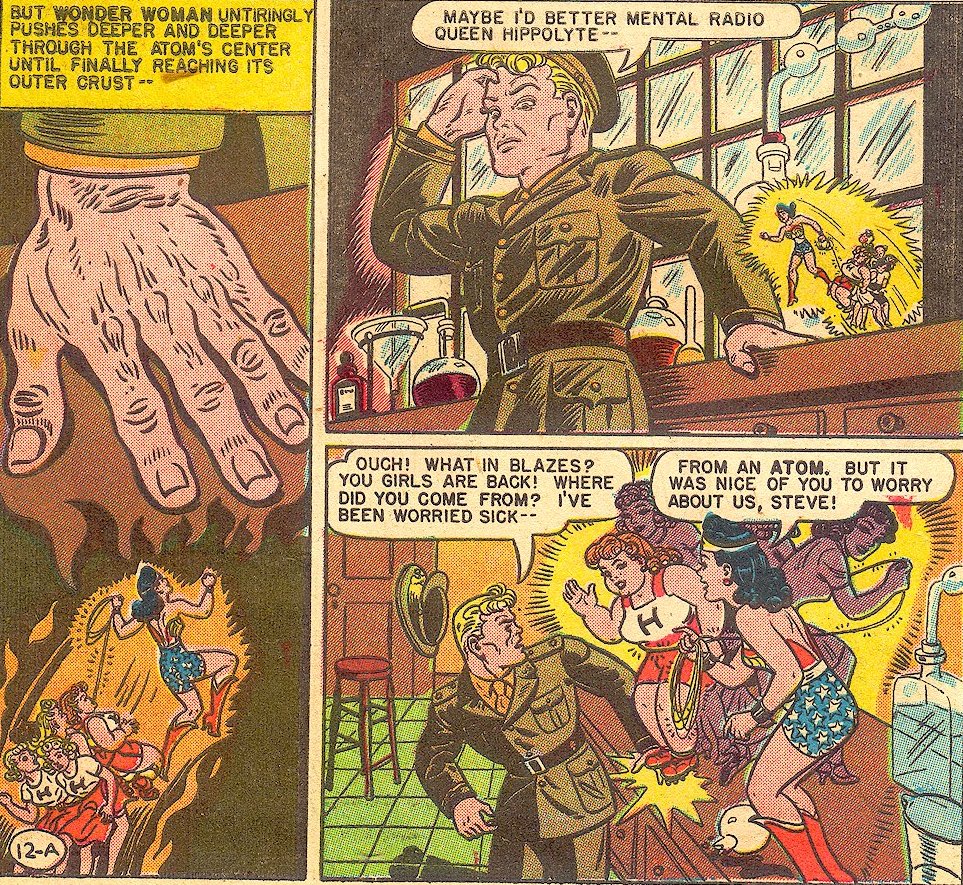

Here Steve is positioned as the doll owner; his giant hand set beside the miniaturized WW and Holiday girls. He is, moreoever, feminized — he’s the worry wort fretting about when hubby will come home. The last panel dialogue could be a sitcom back and forth “Wife: Where were you! I was worried sick!; Husband: Aw, it was so sweet of you to worry you pretty thing!” With a little imagination, you could see this as showing Steve playing with dolls in order to prepare himself for his (proper) feminine roll.

Of course, the genders are also mashed because WW was read by, and aimed at, both boys and girls. Marston wants everyone, boys and girls, to enjoy dominating and controlling femininity in order to teach themselves how to become better women. The male gaze, so despised by feminist film theory, is here seen as the key to ushering in a feminine, and indeed a feminist, utopia, where boys and girls join in joyful sisterhood, and militant atomic power is transformed into love which heals the crippled children.

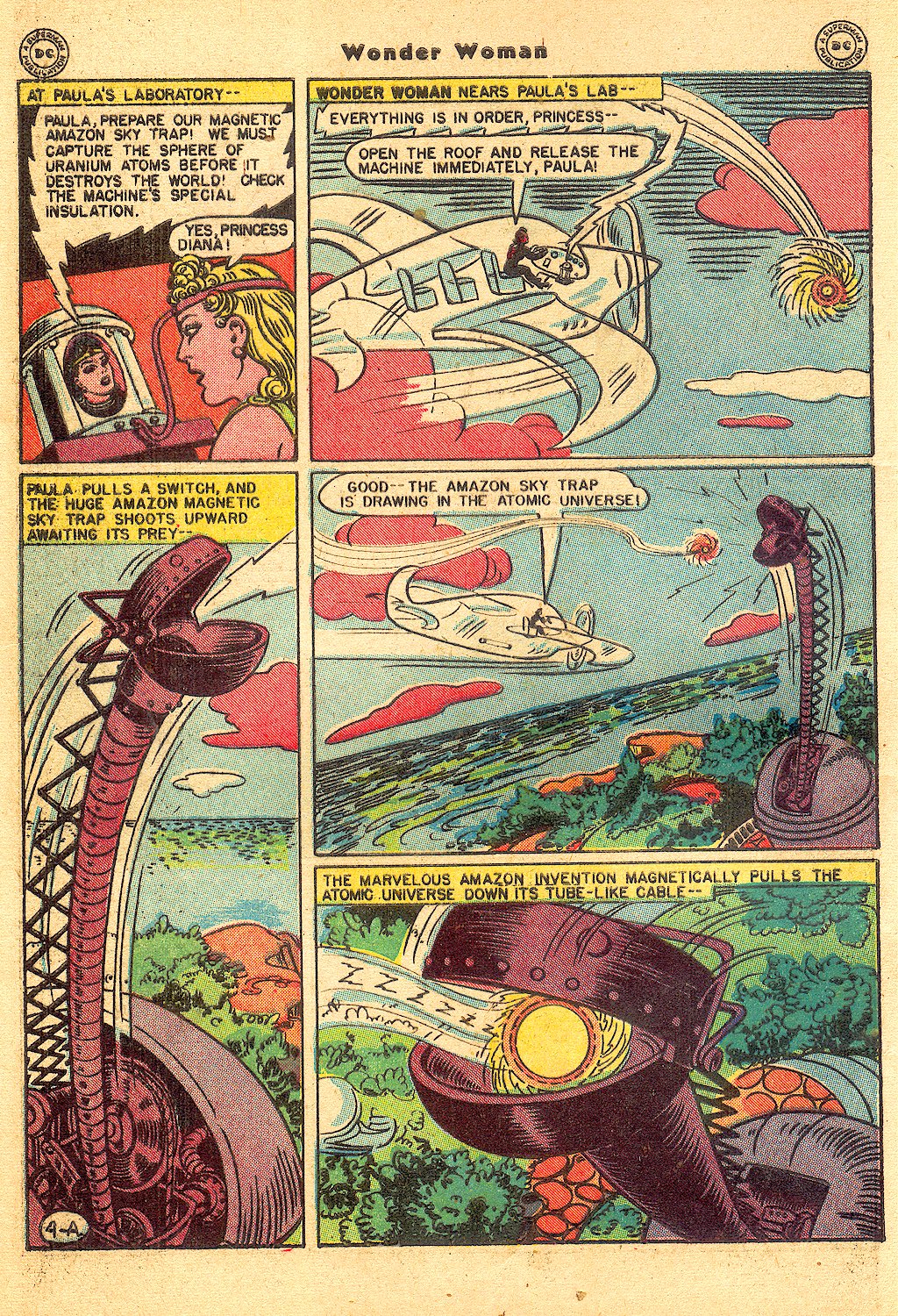

And what better symbol for this new age than…enormous mechanical yanic penis!

__________________

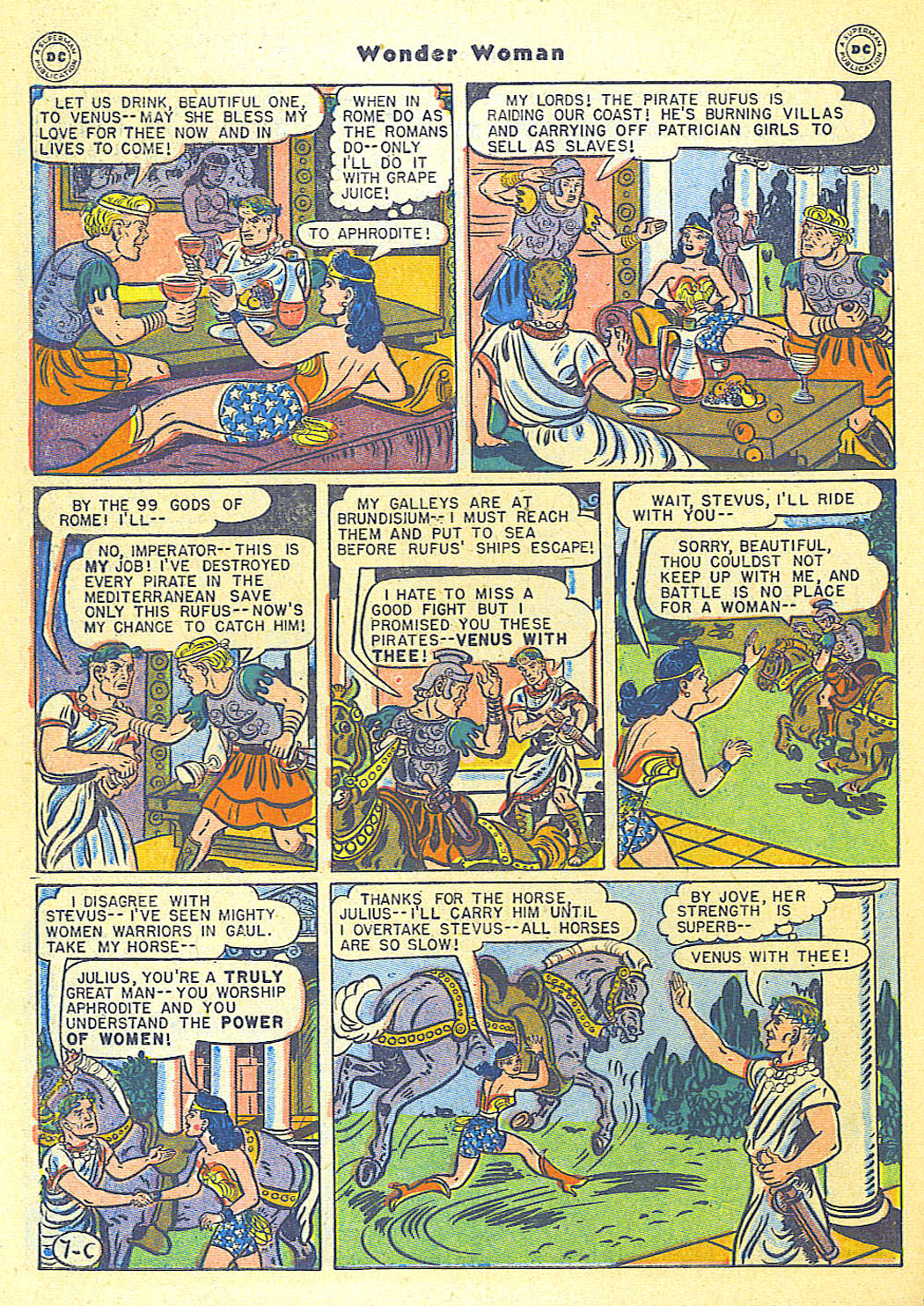

Okay; I have to show this too.

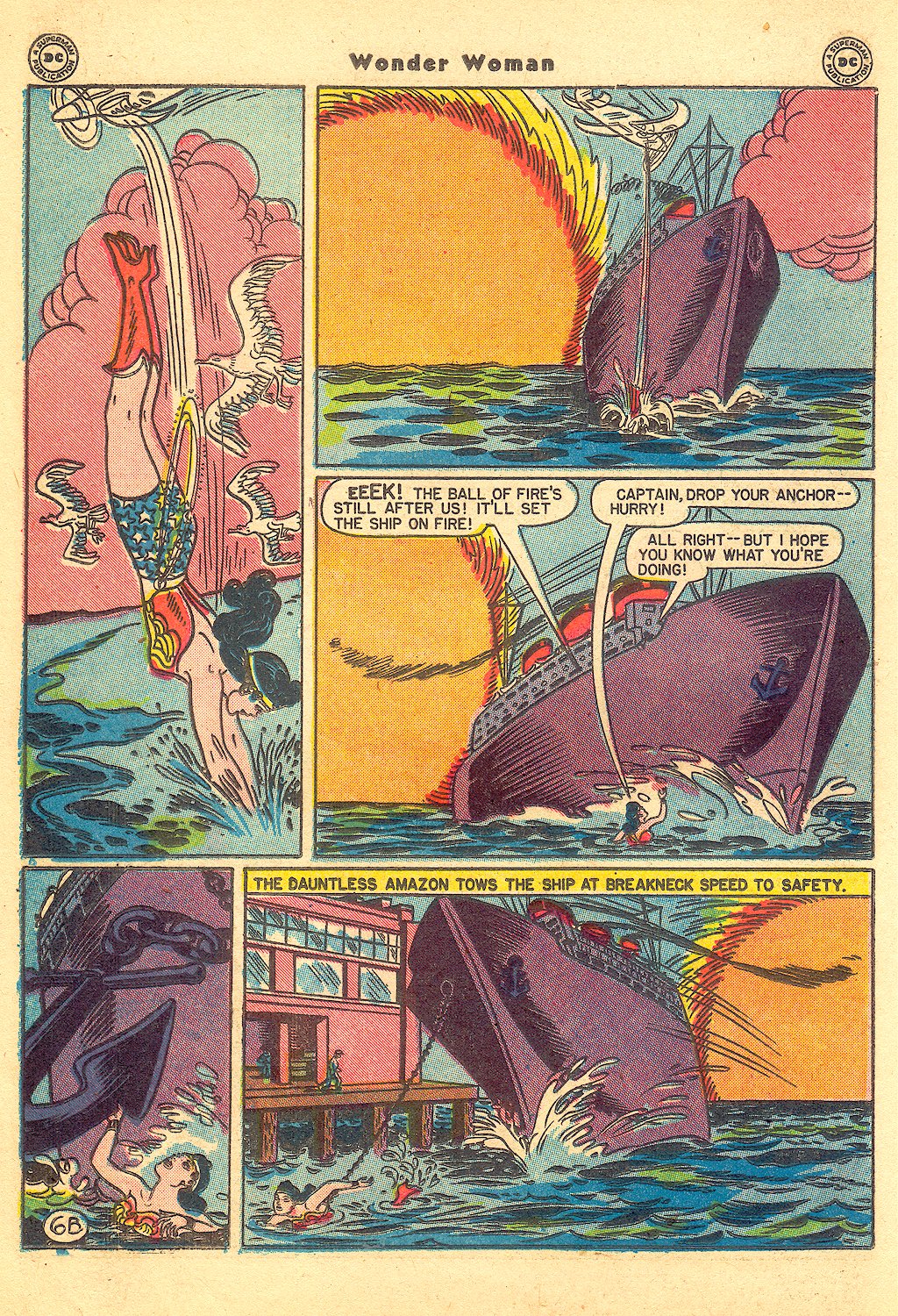

That’s WW rescuing a ship from a runaway overgrown atom.

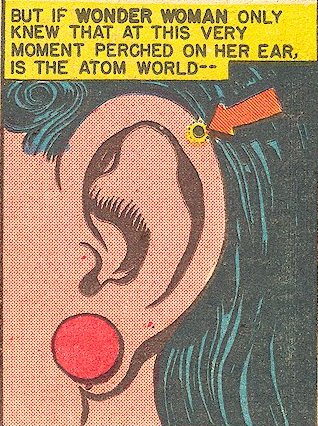

And then there’s this:

My favorite thing about this is that you know — you know — that Marston thinks it’s sexy to have an atomic world filled with women lodged on Wonder Woman’s ear. He’s in his fifties, he’s dying of cancer — and he’s still updating his masturbatory repertoire with the very latest technological advances. It kind of makes me tear up.