Note: Quotes from Joyce Farmer and Lyn Chvli are from interviews with the post’s author.

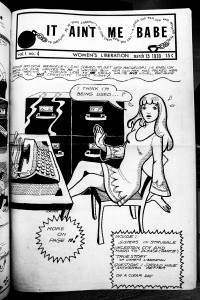

While Wimmen’s Comix can be linked to the feminist newspaper movement of the early 1970s through It Ain’t Me Babe Comix, its arrival was foreshadowed by another all-women underground comic out of Laguna Beach. The first issue of Tits & Clits, by Joyce Farmer and Lyn Chevli, was published just weeks before the first issue of Wimmen’s Comix in 1972. Lyn Chevli had first learned about underground comix through the bookstore Fahrenheit 451, which she owned with her husband. Chevli said, “I took one look at one and it blew my mind. I thought, ‘Oh my god, this is incredible.’ And it just stirred in me, for maybe two weeks, and then I came up with this thought, ‘If I ever sell the store, I’m going to do an underground comic.'” When Chevli parted ways with her husband, the store was about $20,000 in debt, so she decided the time was ripe to start her comic.

Accounts of the anthology’s founding differ between its founders. Chevli said,

I put a little sign in the store, in the window, saying “artists wanted.” And Joyce [Farmer] worked right next door to us [and she] showed up and said, “I’m answering the ad for an artist.”So I said, “Ok, fine, let’s get together and show me some of your work, and let’s see what happens.” She had never seen an underground comic before. She came over to my apartment and I said, “Draw me some stuff,” and she did. And I said, “Ok, draw me something dirty.” Eventually she drew me a woman sitting down on the floor with her legs spread and a rat nibbling at her vulva. And that did it. I said, “That’s perfect. I love it.”…So we got together and we started to work…we had to invent ourselves. We were two nice little girls, college graduates and everything, and here we were getting into the sleaze pit.

Joyce Farmer remembers the meeting a little differently, saying that the comic was Chevli’s idea and that they were put in touch by a mutual friend.

The actual idea for the comic book occurred spontaneously while they were working on the first issue. Chevli said, “One day we were sitting there, drawing, and she shouted it out, ‘Tits & Clits!’ and I just about fell off my stool. I knew it was perfect. I hated her guts for that, but I knew it was a very good idea.” The name was a play on the phrase “tits and ass” often used in men’s magazines. Farmer and Chevli, as well as many of the women who later submitted to Tits & Clits, viewed female sexuality as fertile grounds (pun intended) for the expression of radical sentiments.

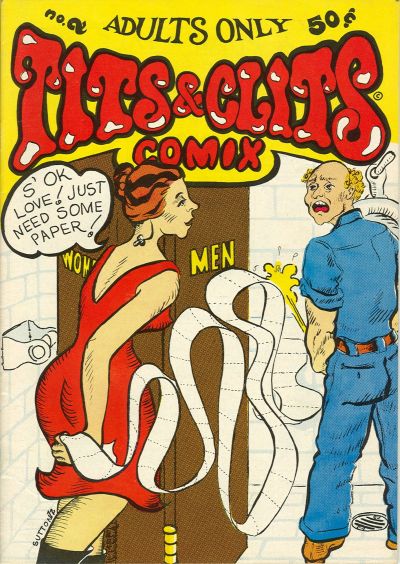

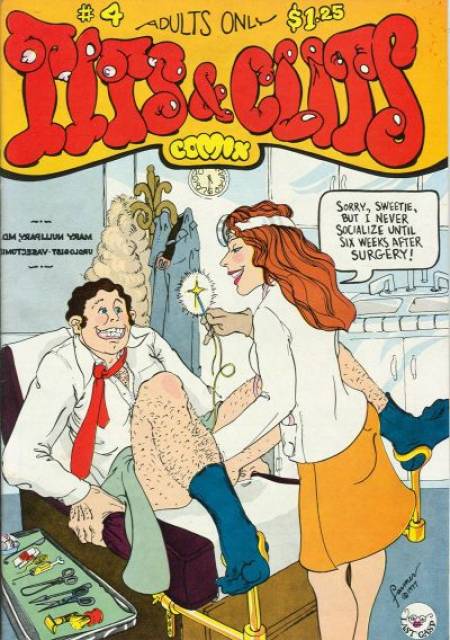

From its inception, Tits & Clits was a fundamentally different anthology than Wimmen’s Comix. Not only was it more single-minded thematically, it completely lacked the collective structure and underlying democratic ideology of Wimmen’s Comix. Whereas Wimmen’s Comix at its inception was a collaborative effort aiming to unite all of the women currently in the underground comix world (and to bring in even more women), Tits & Clits began as a partnership between Joyce Farmer and Lyn Chevli, who created all of the material for Tits & Clits #1 and #2, Pandora’s Box, and Abortion Eve by themselves. (Farmer and Chevli produced seven issues of Tits & Clits between 1972 and 1987.)

Their location in Laguna Beach, removed from the hubbub of San Francisco, meant that they were initially isolated from the other artists in the underground. Farmer recalled, “The weird thing was that we just decided independently to do a comic book and we didn’t discuss it with anybody in San Francisco.” The two artists worked in close conjunction, often trading the work of drawing and writing the stories. Only having two artists doing the work meant that only about one issue was published a year, if that. Chevli and Farmer did eventually bring in other artists from Wimmen’s Comix in order to get their comics published more frequently, but the decision was possibly more practically than ideologically motivated. Chevli preferred not to draw and stopped drawing when they had other artists to do the stories. Tits & Clits tended to feature the same roster of artists rather than purposefully working to include new artists, although Farmer noted that they were open to submissions by new artists.

Chevli and Farmer define Tits & Clits as one of the first (if not the first) self-published underground comic by women. Since they both understood the way in which underground comix worked from reading them — 32 pages of black-and-white content (“guts”), and a front and back cover in color — they simply mimicked the form. Chevli and Farmer self-published their early works (including Pandora’s Box, Abortion Eve, and Tits & Clits #1) as Nanny Goat Productions before ultimately partnering with Ron Turner of Last Gasp for Tits & Clits #2-7 to improve the anthology’s distribution and circulation.

At the outset, Nanny Goat was able to get their work into circulation through Chevli’s bookstore connections. Chevli knew one of the underground comix publishers in Los Angeles, and the artists figured that if they produced their own comic, they could distribute it through that publisher. Chevli commented, however, that other publishers were initially hesitant to be involved in Tits & Clits.

I went to Bob Rita [at the Print Mint] who was a big publisher [and] showed him the book. He looked through it very slowly and very seriously. He said at the end, “Why do you think any woman in her right mind would buy something like this?” I said “Well, because I’m a woman.” He said, “I’m sorry.” He pushed the copy I had given him back to me and said, “I can’t print this. It’s too bad. It’s horrible.” Later on, we were invited to a huge party that he gave, at his home, and he was blushing. He was sorry that he said that. But he didn’t want to show the magazine to anyone else, to any woman. “No, heavens, we have to protect our girls.” That kind of thing. But everybody understood eventually.

For Farmer and Chevli, publishing a book that was so objectionable was a radical act of defiance against what women were supposed to be doing at the time, particularly college-educated women with children. Despite (or because of) its controversial nature, Tits & Clits sold fairly well when it could get distributed, according to the artists. Chevli said, “Our first edition we sold out in 8 months, I think it was. We produced 9 books in ten years and caused all kinds of ruckuses in the county and elsewhere. We sold over 100,000 comics during the 9 years and were relatively successful.” Farmer agreed, “Tits & Clits sold like wildfire when we could get distributed.” Both artists note that they never made very much money off Tits & Clits, however, since each issue only sold for $0.75 to $1.50.

Tits & Clits, as a sex comic produced by women, provoked a great deal of uproar within and beyond the comix community. According to Farmer, Tits & Clits made people uncomfortable and therefore was not widely read or distributed. Even just the name of the anthology was often considered obscene; the book was often left out of magazines or newsletters as it simply could not be put into print. Farmer said,

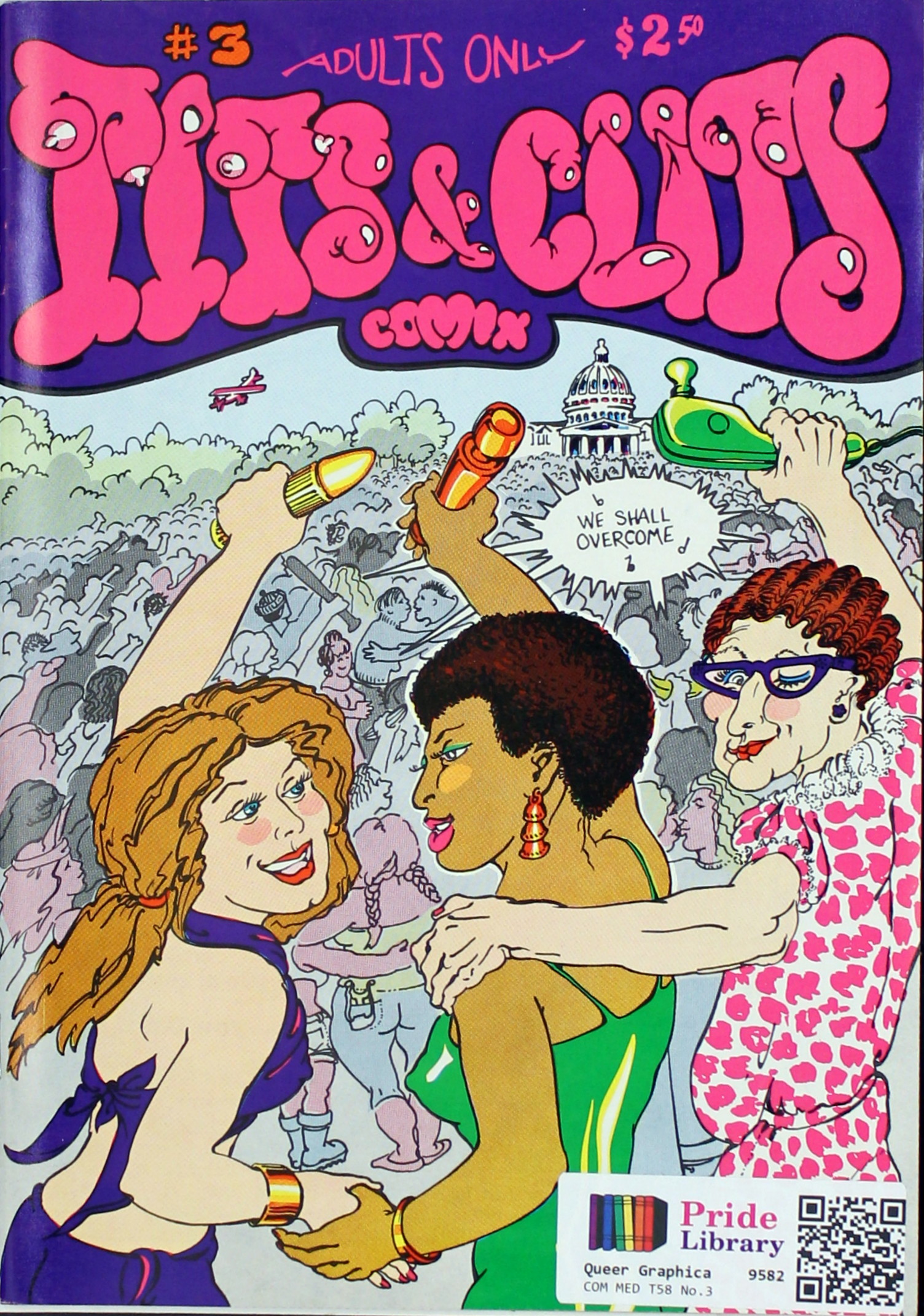

[It was controversial because it was] sex from a woman’s point of view, a woman’s body from a woman’s point of view. Hustler didn’t even come out until 1973 or so, so we were saying things about women and women’s bodies that had just not been said in print…Women have been considered dirty for so many centuries that we were just breaking into that and saying, “Yeah, we’re dirty, ha ha, here, have some.”

Chevli added, “What could be worse than telling the truth about female sexuality, and how men treat women … In that age, it was not considered nice for women to do [that]. And that’s what exactly we wanted to pull out and show and exhibit and push in people’s faces.” The confrontation of Tits & Clits was not only that it talked about women’s sex lives truthfully, but that it did so from a woman’s viewpoint. Tits & Clits, in significantly eroding the private/public boundary, delved deep into the realm of the personal, so deep that it went well beyond mainstream feminist thought at the time, at least according to Farmer and Chevli.