I’ve been doing a series of posts about superheroes and gender. In the most recent I talked about superdickery. Superdickery here refers to the way super-heroes tend to stand in for the uber-patriarch, both as benign law-giver and as evil ogre-father. In the post, I talked especially about how Marvel’s innovation was to shift more explicitly towards the idea of superhero as nightmare ogre-father (the Hulk! the Thing!) Ultimately, though, the ogre-father is still the father; Marvel comics are still about dreams of empowerment, rather than about denigrating or undermining those visions of absolute mastery.

Okay. So…if superheroing is all about superdickery, what happens when you have a female superhero? As the title up there says, can Wonder Woman be a superdick? And, if so, how, if at all, is that dickishness different when it’s attached to a woman?

There have been a couple of gestures at making Wonder Woman dickish. As I mentioned last post, Kate Beaton’s butch WW can be seen as dickish to some extent. And Greg Rucka’s WW in the Hiketeia might be considered superdickish in some sense too.

Overall, though, male writers have seemed distinctly uncomfortable with having Wonder Woman act as a superdick. I’m going to talk about some specific examples in a minute. First though, I want to discuss briefly why the superdickery meme is so hard (as it were) to apply to female characters.

In general, the whole point of the superdick is that you have some non-powered weakling (Bruce Banner, Clark Kent, whoever), and then the superhero acts as empowerment fantasy. Bruce Banner can’t lay down the law — but Hulk can smash. Peter Parker can’t replace Unlce Ben — but Spider-Man can! Bruce Wayne cant’ fight evil in his undies — but Batman will. Etc.

On the one hand, this is a pretty simple formulation. On the other hand, though, it is, I think, plugged into some fairly profound dynamics around male identity. As I discussed in this post, this post, and this post, male identity is built around a central incoherence. This incoherence can be seen as biologically Oedipal (with Freud), or as cultural (with Eve Sedgwick.) Either way, the point is that a male is both identified with patriarchal power (the father) and distanced from that power (the child.) To be identified with patriarchal power is to turn one’s back on femininity, and in some sense on humanity — so that the uberpatriarch is both a monster and, in some sense, unmasculine, since he rejects women (what gender is the Thing under those briefs, exactly?) But, on the other hand, to be a sniveling child outside of patriarchal power is to be feminized.

In short, the engine behind the super-hero split identity is the anxiety of maleness. Peter/Spider-Man is constantly vacillating between two people because neither one is stable. Peter is under pressure to take up the rod of superdickery and become a real man; Spider-Man is under pressure to cast aside the rod of superdickery and pay attention to the girls already so he can become a real man.

Women aren’t implicated in this psychodrama. Female identity isn’t incoherent — or at least, it’s not incoherent in the same way. A commenter on a recent article of mine at Reason put the point succinctly:

girls can think ninjas are cool without any blowback. Any man who likes sparkly emo vampires is probably sorting through some issues.

That’s exactly the point; a girl who likes ninjas doesn’t have her femininity called into question (on the contrary, butch women are often considered especially hot, as I argue here. Men who like romance, on the other hand, open themselves up (as it were) to the charge of not being sufficiently masculine.

So that means women have it easy compared to poor, conflicted men, right? Well, not exactly. It’s true that female identity is in some sense more stable…but there’s a certain amount of coercion which goes into enforcing that stability. Men are always defined by their lack of the phallus, always anxiously scurrying after the unattainable superdick…or dropping it like a hot potato and scurrying away when they get it. Women, on the other hand, aren’t supposed to have the superdick in the first place, so they’re just kind of supposed to sit there and be. Basically, for women, the ideal is more coherent, which means that individual slip ups (watching ninja movies) aren’t necessarily always as important. However, overall, a more coherent ideal can actually be more limiting. Always striving and failing is tiresome, but probably preferable overall to being stuck in prison.

Which brings us back to Wonder Woman.

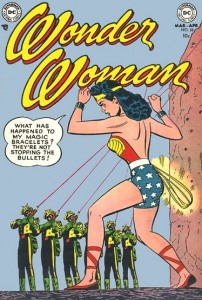

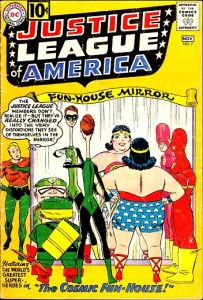

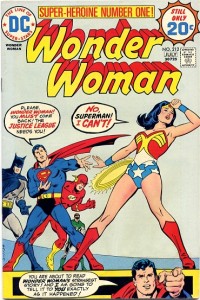

That’s from Denny O’Neil and Mike Sekowsy’s first issue on WW from 1968. And, as you can see, the creators seem to be of the opinion that WW is a freak. And why is she a freak? Not because she’s actually a monster like the Thing, but simply because she’s got “muscles” and is a woman. And, not coincidentally, in the following issues of their run on the series, O’Neill and Sekowsky actually depowered WW, turning her into a civilian spy — still a crime fighter, but one who wouldn’t necessarily scare the (male) kiddies.

O’Neill and Sekowsky are more blatant than most, but they’re hardly alone in their discomfort with the super-powered WW. Throughout “The Greatest Wonder Woman Stories Ever Told,” there’s a constant, insistent effort to evade the image of Wonder Woman as superdick — to domesticate her, if you will. In Robert Kanigher’s “Top Secret,” Steve Trevor engages in an elaborate plot to get Wonder Woman to marry him. His scheme fails…but it forces WW to create her Diana Prince identity in which (of course) she serves under Steve in the military. In this story, then, Wonder Woman isn’t Diana’s empowerment fantasy; rather, Diana is *Steve’s* empowerment fantasy. WW does get the better of Steve, but only by doing what he wants. She bows to his superdickery and relinquishes her own.

Similarly, in Robert Kanigher’s revealingly titled “Be Wonder Woman…and Die!” the emotional focus of the story is on a terminally ill young actress who impersonates Wonder Woman and then expires beautifully. It’s pretty clearly a Mary Sue story in some sense — a WW fan appears, is lauded by her idol, and then shuffles off the mortal coil to great acclaim. But you do have to wonder — if this is a Mary Sue, whose Mary Sue is it? Who exactly is getting off on a depowered and dead WW clone? Could it be the male writer,by chance?

One final example; Wonder Woman #230, from 1977. (Todd Munson very kindly gave me this issue when I visited his class at Randolph-Macon a few weeks back. ) This issue is by Marty Pasko, and it’s set in the 1940s to tie in with the then-current TV series. It’s also obsessed with doubling. The villain is the Cheetah, who suffers from multiple-personality disorder; normally she’s an everyday socialite (Priscilla Rich), but when she sees Wonder Woman she has a psychotic episode and turns into a supervillain. In this sotry, Priscilla accidentally encounters WW and has her transformation triggered. As the Cheetah she then manages to discover WW’s secret identity, and makes plans to use the information to kill her. However, Cheetah turns back to Priscilla before she can take action. Priscilla then contacts Diana Prince…and hypnotizes her into forgetting she’s Wonder Woman, figuring that if Wonder Woman disappears, Priscilla herself will never change into the Cheetah again.

So along the way here there are several suggestive incidents.

— Early in the issue, Steve Trevor is gushing on and on about Wonder Woman. Diana Prince is clearly quite pissed about this; she’s jealous of her alter ego. Thus, there’s a definite implication that Diana *wants* to get rid of WW, just as Priscilla wants to get rid of the Cheetah.

— There’s an erotic tension between the female antagonists. Priscilla’s repressed emotions are released whenever she sees Wonder Woman; it’s not hard to read a lesbian subtext into that. Moreover, the hypnotic encounter between Priscilla and Diana is framed as seduction; Priscilla even comments (lasciviously?) on how “naive” Diana is.

In breaking the mirror here, Priscilla is banishing both Wonder Woman and the Cheetah. Where agonized male-male tensions tend to lead to heroes hitting villains and hyperbolic violence, the female-female encounter/seduction does the reverse. It doesn’t redouble anxieties around female identity; it eliminates them. Priscilla is ushering Diana back into femininity. (I don’t think it’s a coincidence that in the last panel Diana’s face seems definitely softer and less butch than it does towards the top of the page.)

Priscilla can be seen, in other words, as patrolling the boundaries of femininity. This is actually a fairly common dynamic, I think; women are often harsher on (small) infractions against femininity than men are. My wife pointed out that Patti Smith in the 70s once commented that there’s nothing more disgusting than seeing some woman’s breast hanging over a guitar. The quote is interesting too, because, like this encounter, there’s definitely some not quite dealt with eroticism there; Smith is perceiving female guitarists as sexual beings; there’s a same-sex frisson. I haven’t quite worked this through, but it seems like there’s a parallel here with Eve Sedgwick’s ideas about male homosociality. That is, men form homosocial bonds (and repress explicit homosexual ones) as a way of cementing patriarchal power. Women might be seen as forming homosocial bonds (and repressing explicit homosexual ones) as a way of policing or reaffirming femininity — which again essentially has the effect of cementing patriarchal power. That seems like a good description of what Priscilla is doing here, certainly — she seduces/explains the error of her ways to Diana in order to prevent Diana from becoming a superdick, and so leading Priscilla herself into superdickery.

On the one hand this ends up being a false consciousness argument (women reinforcing the patriarchal order out of a mistaken fear of their own power/acceptance of their natural role.) On the other hand, it might also be seen as a not unrational risk assessment. Priscilla is worried that Wonder Woman’s escape from femininity will bring reprisals against Priscilla herself (she’ll become the cheetah, get herself in trouble, and end up being punished.) Similarly, Patti Smith, as a female rockstar, could be seen as covering her own ass — too many female rockstars might cause trouble.

I don’t know; not sure that that’s all thought through as well as I might like. But I think there is definitely a sense in which bonds between women are used to patrol femininity just as bonds between men are used to patrol masculinity. And the obsessively doubled relationship between Priscilla/Cheetah and Diana/Wonder Woman seems to get at that.

Though at the same time, of course, there’s a tradition of feminist sisterhood which is about confronting or challenging patriarchy. It’s interesting in that regard how, even though this is set in the 40s when the Marston /Peter stories took place, there are just a lot less women here than in Marston’s writing. The only woman who’s around is Priscilla, which is obviously an antagonistic relationship….

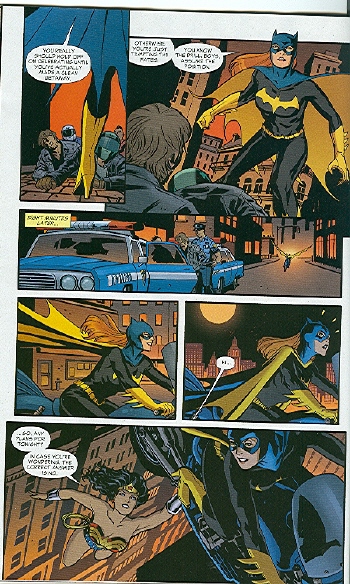

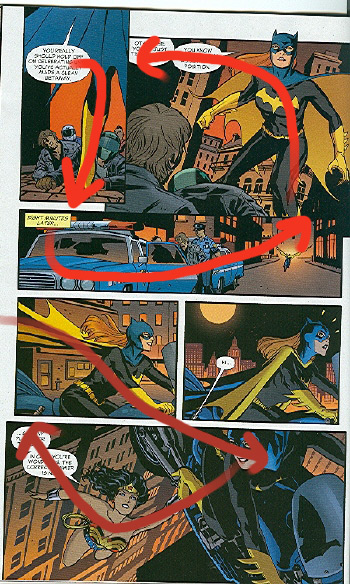

— Because WW has disappeared, Steve has to take her spot in a video. (The director comments “I’d rather shoot a war hero than some broad in a silly get-up anyway!”) The Cheetah has booby-trapped the camera, though. Priscilla doesn’t want to kill anyone…so she figures she has to remind Diana of who she was. She leads Diana off to the side (which looks again very much like femme/butch seduction)

and this time the female/female encounter brings WW and the Cheetah both back.

Because we see this entirely from Priscilla’s perspective, though, this comes across more as sad necessity than triumphant victory. The return of female superpowers may be necessary, but it’s not ideal or normal. And, moreover, it really does result in bad news for Priscilla; she gets beaten up, captured, and sent off to Paradise Island for reeducation (where presumably she’ll be reintegrated back into femininity.)

—Soon after WW reappears we get this panel:

The reappearance of WW seems to humorously undermine Steve’s maleness. When a woman wields the superdick, men are less male. Not only can’t Steve take WW’s place, but even in wanting to he becomes ridiculous; less of a man.

— The comic ends with WW back in Diana Prince identity, talking to Steve. Steve is worrying about the possibility of WW disappearing again — and Diana suggests that if WW does disappear Steve should spend more time looking for her. There’s certainly a hint here that Diana would like WW to go away— she wants Steve to recognize, or respond, to Diana instead. Like Priscilla, Diana seems to in part want to lose her super-powers and her super-identity.

This isn’t that unusual a trope — as I mentioned in the last post, Spider-Man often wants to lost his powers, as does Bruce Banner, and so forth. The difference here is, perhaps, that when Diana is just Diana, there’s no indication that she wants to be anything else. She doesn’t wish she had her powers back, or think about WW. Instead, Priscilla has to remind her who she was. When Peter Parker, or whoever, is depowered, his identity remains incoherent; he still wants the superdick. But for Diana, the only tension is when she’s Wonder Woman. A feminized Diana, sans superdick, is perfectly happy — just as, presumably, a Priscilla without the Cheetah would be perfectly happy. There isn’t the attraction/repulsion for patriarchal authority that you tend to feel in male super-hero narratives. Instead, the energy of the story seems to push pretty firmly towards just turning superfemales into ordinary women and being done with it. Of course, it can’t end up there because, you know, Wonder Woman’s name is on the cover of the comic, and you need more stories with her. But that isn’t Marty Pasko’s fault. He didn’t create the character.

And next time we’ll talk about the guy who did create the character and how he felt about superdickery. Hopefully we’ll get to that next week.

In the meantime…this is actually part of a long series of posts on latter-day Wonder Woman iterations. You can read the whole series here.