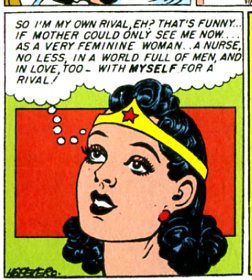

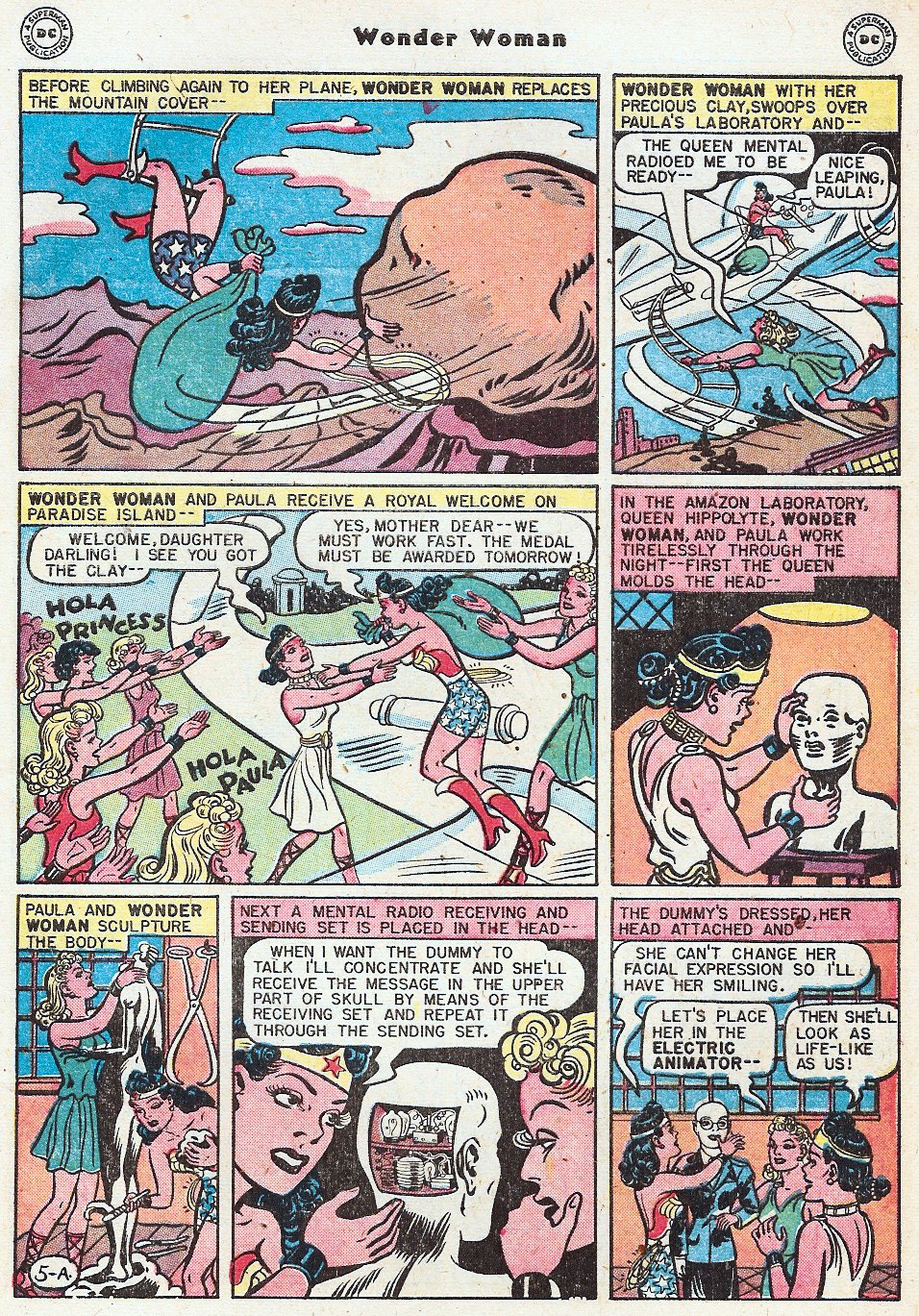

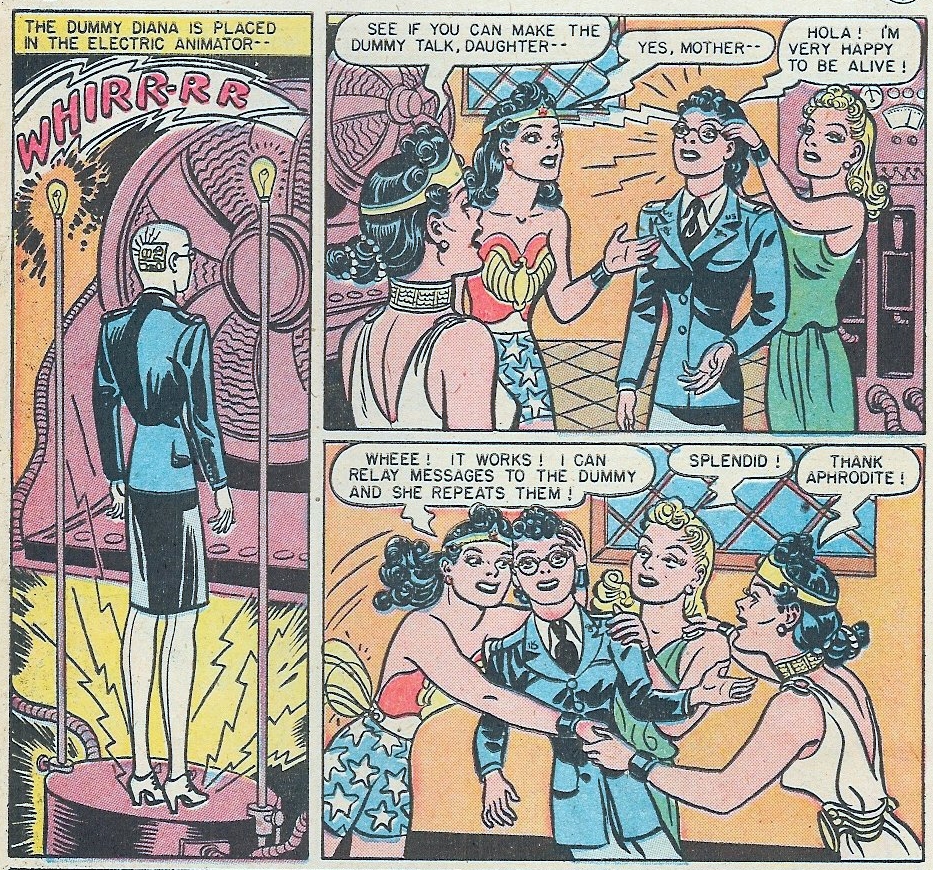

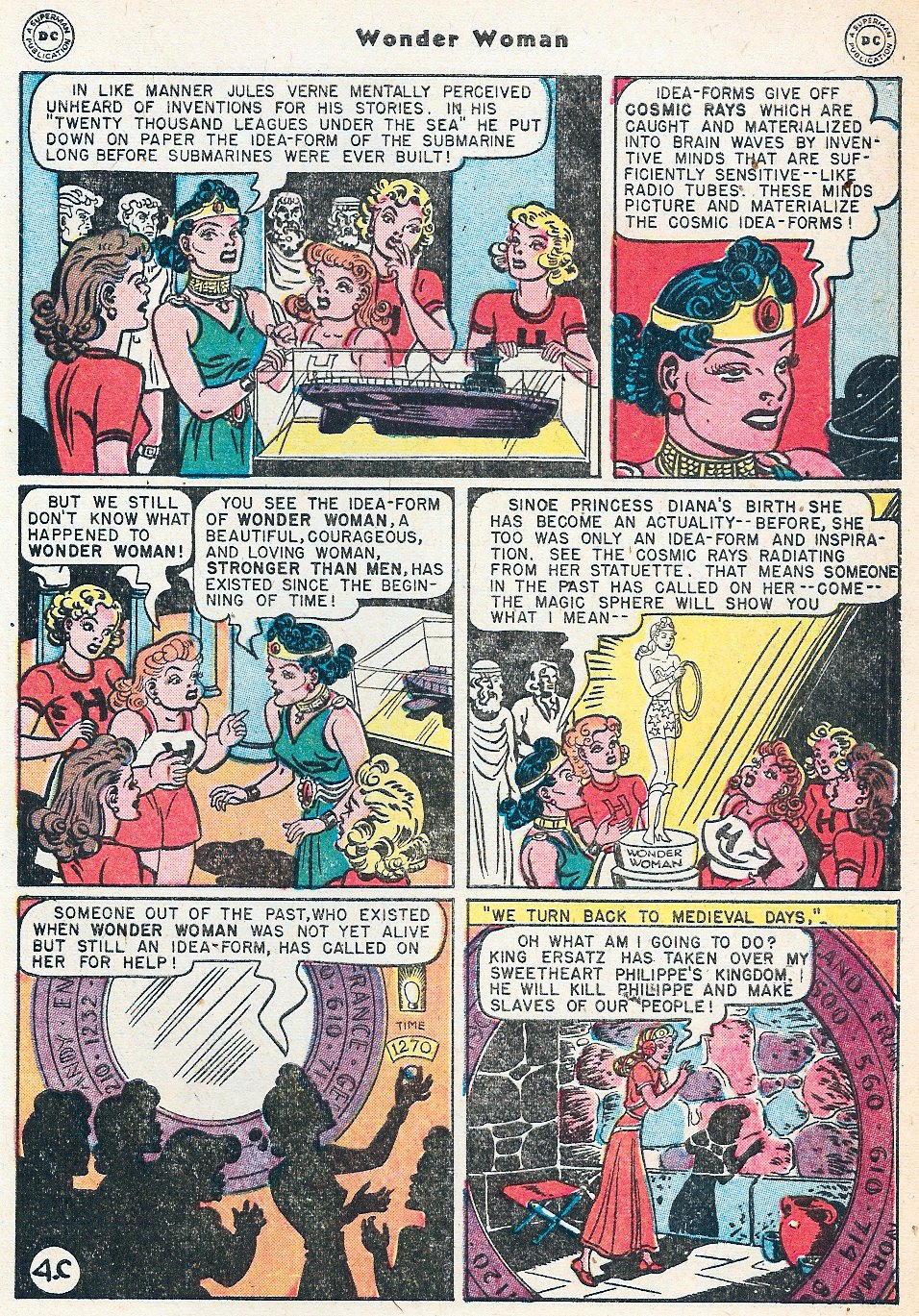

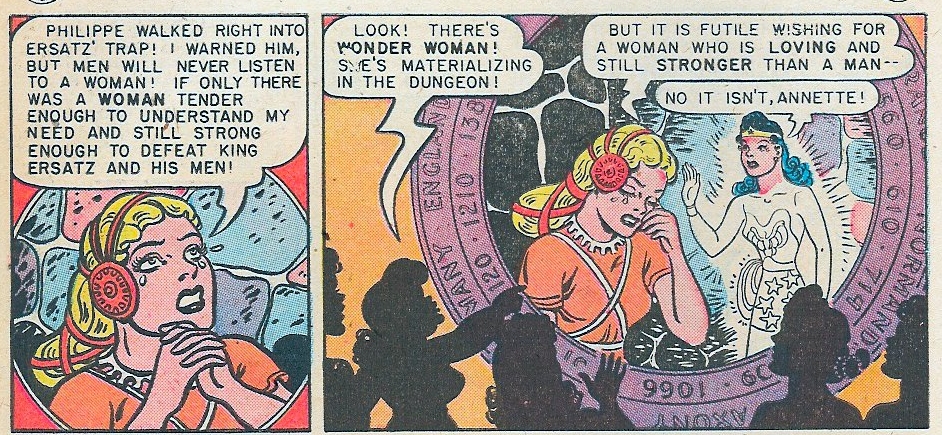

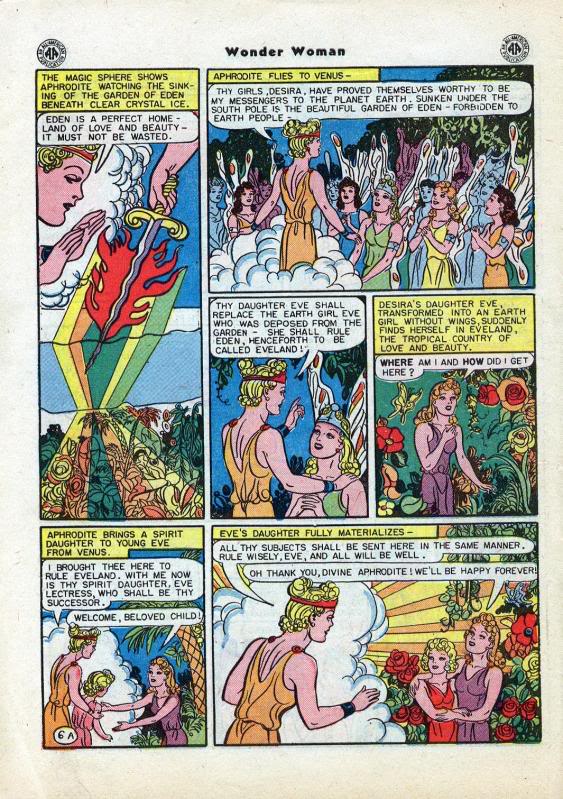

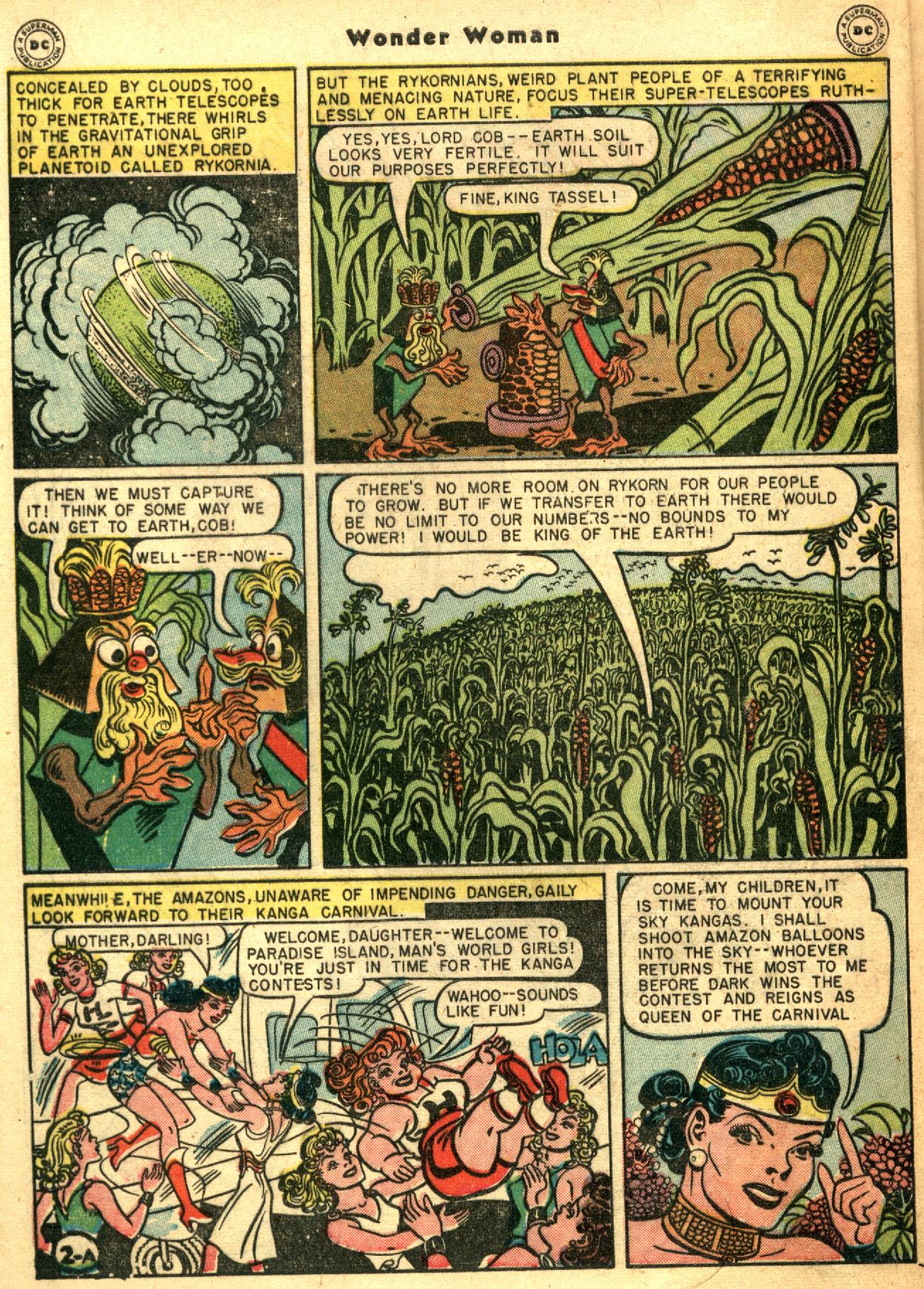

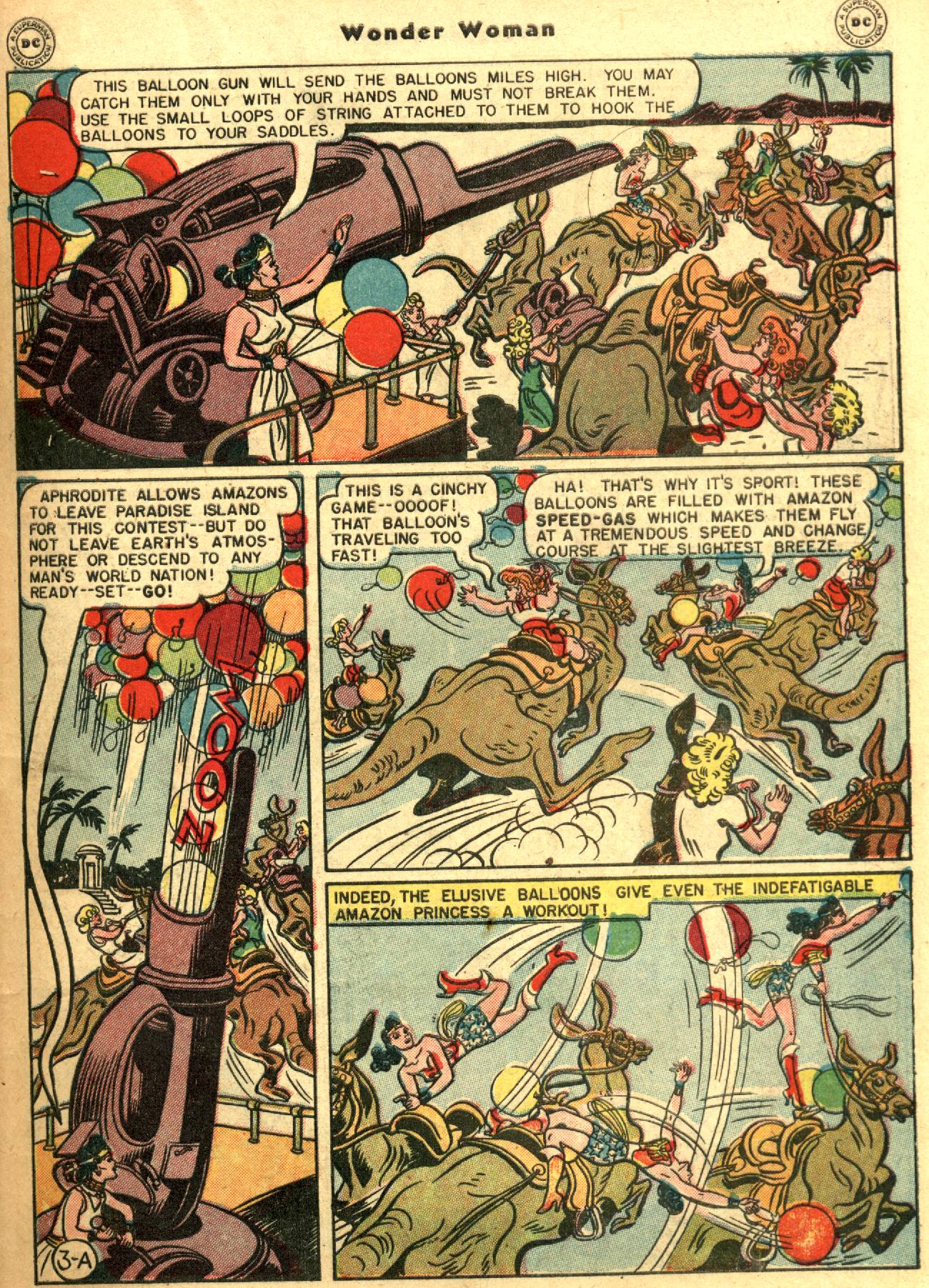

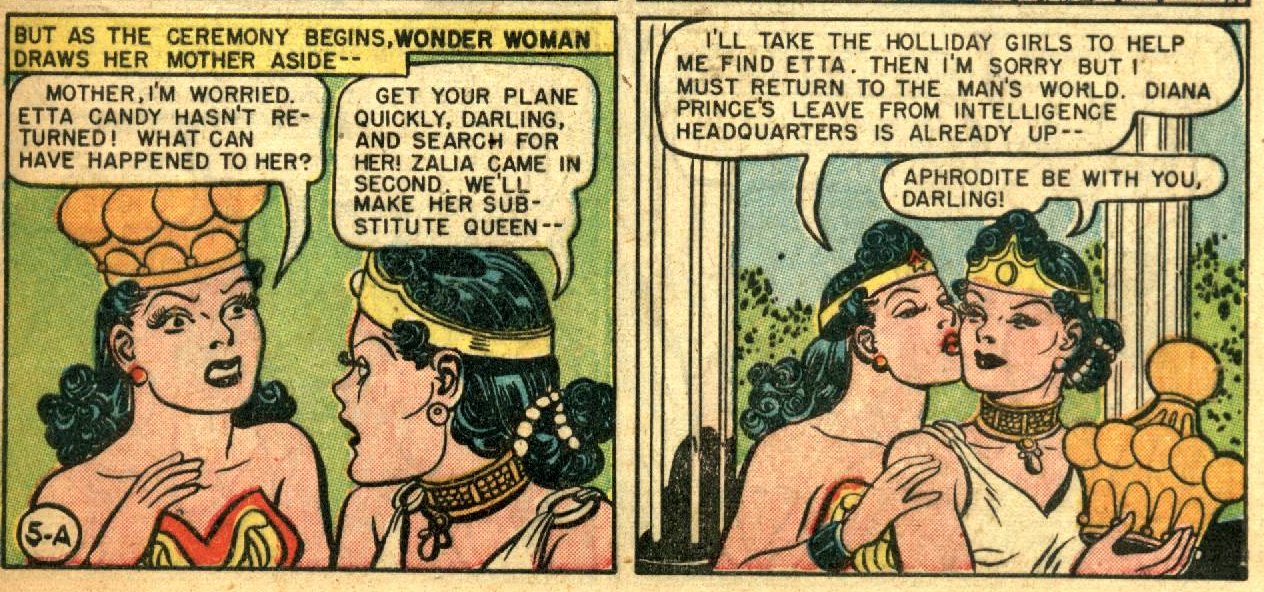

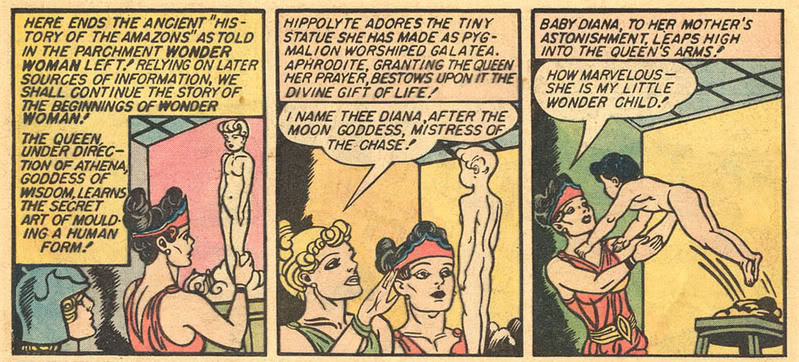

I wrote a little about the Azzarello Amazons in the latest Wonder Woman series, or at least on the description of the them I heard second-hand. For those not in the know, Azzarello has the Amazons be lying, murdering, borderline rapists. I thought this was a pretty awful desecration of Marston.

There were a couple of interesting comments on the post. John argued:

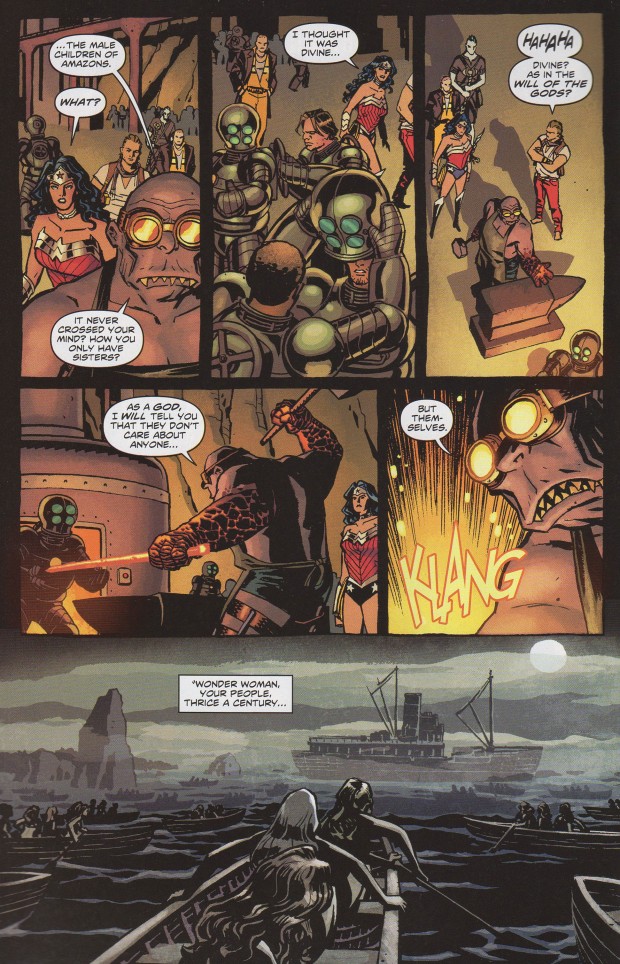

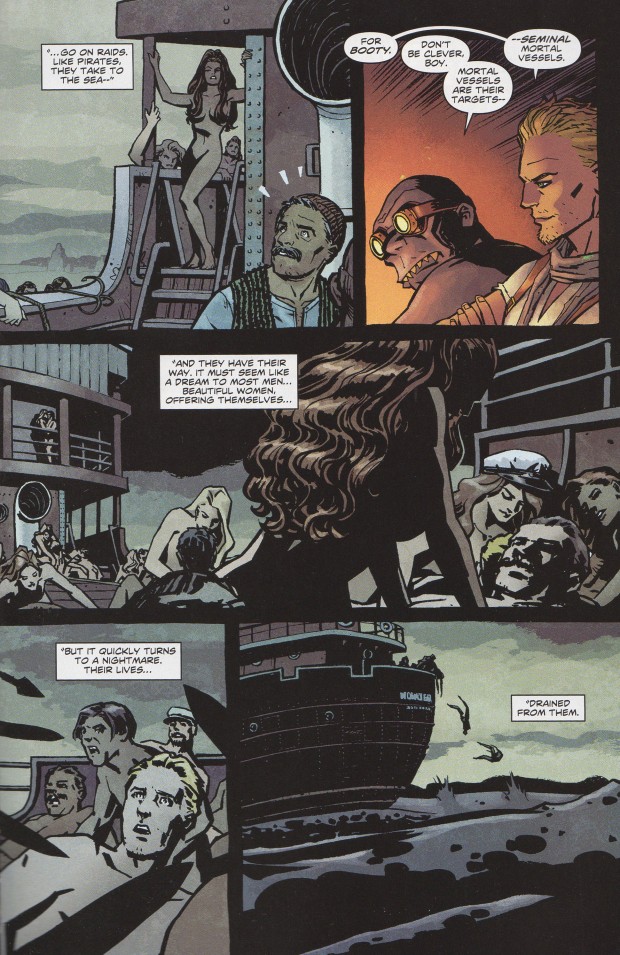

What you’ve just described as a “misogynist horror fever dream” is about two pages of the arc so far — two pages depicting the Amazons as the source of disappeared ships on the Bermuda Triangle. They have sex — depicted as primarily consensual — with men, then kill them. They sell any male children they bear (to Hesphaestus, who as it turns out is not cruel to them.)

I read it as part of Azzarello’s generally nasty outlook on life and specifically nasty outlook on Greek myths. Because it’s of a piece with reimagining Hades as a creepy child with melted candlewax for a head, and Poseidon as a hideous fish-beast, etc, and portraying every single god shown so far as a monster or a dick, I didn’t read it as specifically anti-woman. It’s just Azzarello’s cynicism.

Charles Reece also weighed in, arguing among other things:

(1) I don’t see it as necessarily suggesting that’s the way things would be in reality (e.g., “a society of women living together must be perverted, violent, evil, and anti-men”), but as a possible way of getting to people to deal with fears that already exist. Such fiction doesn’t have to be Birth of a Nation. (2) It’s also a way of questioning whether the majority power is inherently wrapped up in the qualities of those holding the power, or if there’s something about hegemony that tends to erase the differences in groups once they’ve achieved that status. That is, are these women acting like men, or are they acting like a group with absolute power? I suspect that your reaction to White Man’s Burden would be that the film is a racist vision of blacks, rather than an attempt to get whites and blacks to see things from an inverted viewpoint (I’m not saying the movie is worth a shit, of course).

So now I’ve read a few issues of the series (5, 6, and 7, I believe). I thought I’d go back to this.

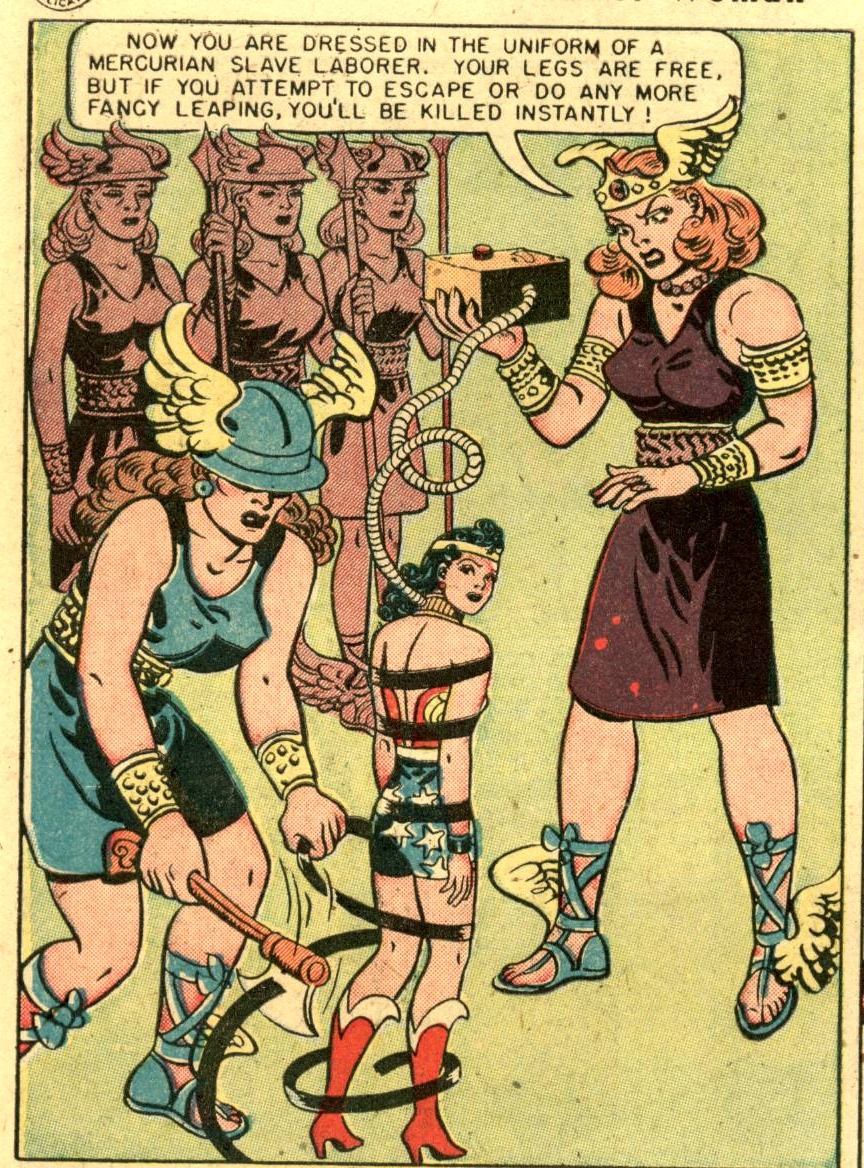

Here’s the sequence in question, narrated by Hephaestus, the god of forging things.

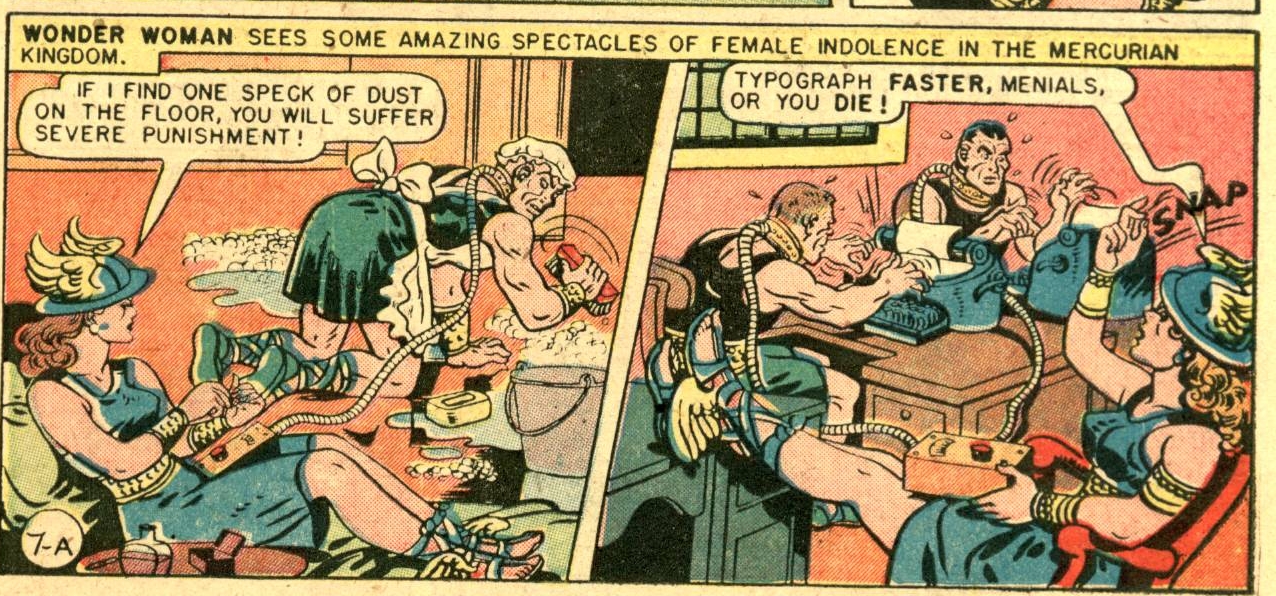

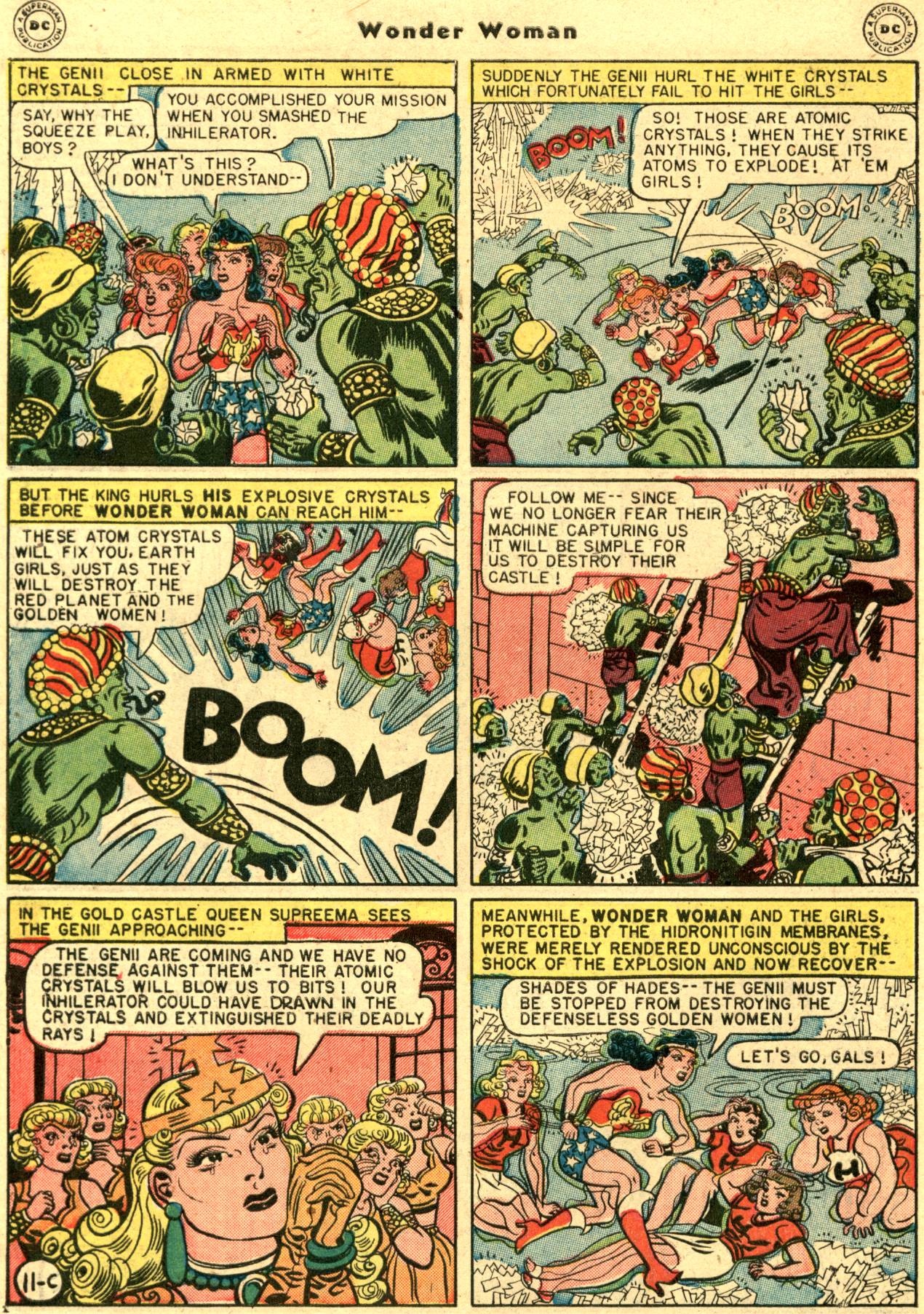

As Charles intimates, if you read through this, you see that Azzarello and Chiang aren’t just making evil Amazons. Rather, they’re using the evil Amazons to flip the history of gender oppression. Throughout history, women have overwhelmingly been the victims of sexual violence…and when men have suffered sexual violence it has also been overwhelmingly (not always, but overwhelmingly) at the hands of men. So here, instead, it is men who are sexually used, and women who do the using. Similarly, throughout history, it has been girl children who have been the victims of infanticide and exposure, and girl children who have been treated as unwanted byproducts. Here, though, in accord I believe with Greek legends, it is boys who are cast off.

Charles argues that this is a means of getting us to think about power dynamics; it’s showing us that the issue is not male/female, but group-in-power/group-out-of-power. If you give people power, they will become exploiters. That’s a universal truth, supposedly Azzarello is knocking the stuffing out of Marston/Peter’s women-veneration (a women-veneration that even Gloria Steinem found troubling, incidentally). Through that stuffing-knocking, he shows that hegemony is not fixed, but fungible.

This is, in short, another example of the ever-popular sci-fi metaphorical approach to issues of discrimination. Rather than looking at how race or class or gender effects the characters, you simply map these effects onto a different set of relationships. This creates new insights (everybody would be oppressors if they could!) while also adding the thrill of novelty (women perpetuating sexual violence! how cool is that?) Powerful messages and cheap thrills; what more could you want from your superhero comics?

I think, in response, it’s worth considering the opening of Shulamith Firestone’s radical feminist classic, The Dialectic of Sex.

Sex class is so deep as to be invisible. Or it may appear as a superficial inequality, one that can be solved by merely a few reforms, or perhaps by the full integration of women into the labor force. But the reaction of the common man, woman, and child — “That? Why you can’t change that! You must be out of your mind!” — is the closest to the truth. We are talking about something every bit as deep as that. This gut reaction — the assumption that, even when they don’t know it, feminists are talking about changing a fundamental biological condition — is an honest one.

In her conclusion, she says, “Nature produced the fundamental inequality — half the human race must bear and rear the children of all of them — which was later consolidated, institutionalized, in the interests of men.”

Firestone’s point is that the oppression of women is rooted deep in culture, based even upon biology — specifically on differences in relation to children and child-rearing. Firestone looks hopefully to new technologies of reproduction in the hope that they might change the relationship between men and women…and indeed, to some extent birth control has done that. But differences remain, and inequities remain — and those differences and inequities are not simply accidents, or random distributions of power which can be reshaped at a whim. They have long, long years of history behind them, and overturning them has taken equally long years of struggle.

Thus, simply reversing gendered oppression tends to make light of how deeply ingrained these issues of oppression are. The possibility of rape, for example, has a lot (not everything, but a lot) to do with our biological plumbing. Susan Brownmiller argues that “Man’s structural capacity to rape and woman’s corresponding structural vulnerability are as basic to the physiology of both our sexes as the primal act of sex itself.”

That’s perhaps extreme…but if you doubt that rape is not easily reversible, look again at those Azzarello/Chiang pages above. Charles would like the pages to show us that hegemony is not attached to particular bodies or histories; that power, rather than gender or past, is the ultimate truth. As I said, Azzarello and Chiang are reversing the tropes…but there are limits to how far they’re willing to go. Most notably, the men are not actually raped, because, presumably, Azzarello and Chiang can’t, or are reluctant to, figure out a way to violate men the way that men have historically and in great numbers violated women. Instead, they just assume that all the men in question would be happy to fuck random women at the drop of an anchor.

Moreover, look at the top two panels of the second page. In the first, we get to be in the position of the happy sailors, staring at some prime cheesecake (do the Amazons subscribe to Maxim, or are we supposed to believe that all women everywhere naturally adopt such poses?) In the second panel, we get a series of stupid jokes…because sexual assault is funny when women do it, get it? And, of course, on the remainder of the page the sex is significantly more explicit than the violence. Azzarello and Chiang are happy to show us women in the act, but the murder/castration is only suggested by some blades, and then by bodies falling into the water at a distance. The reader participates vicariously in the screwing, but gets to back off for the consequences.

Thus, the Amazons, even as they take the male position of oppressor, are still objects of a male narrative, and, indeed, of a male gaze. They are presented as sexual objects, and the bloodthirsty reversal is almost an afterthought…or, perhaps we should say, an excuse. Certainly, I don’t see any real commitment to thinking about power as a pragmatic, overarching truth. There’s no effort, for example, to use the switch to make men participate viscerally or emotionally in oppression, as you get in some rape-revenge narratives. Instead, I see pulp titillation, complete with snickering, coupled with dunderheaded pulp misogyny, which disavows the violence of the male fantasy by the simple expedient of blaming the whole thing on women. It feels fundamentally thoughtless and dishonest.

The rest of the context only tends to confirm this impression. Wonder Woman, who has newly discovered that Zeus is her father, wanders around obsessed with her patriarchal lineage. Other characters are constantly telling her how well she’ll fit in with the rest of the Gods — she’s her father’s daughter. She concocts an elaborate plan (with the unwitting help of her uncles) to humiliate her father’s wife, Hera — so much for Marston’s themes of feminist sisterhood. Admittedly, Wonder Woman does have a close female friendship…but it seems to be largely based on the fact that her friend is carrying a baby which is related to WW — again, the motivations seem to be all about patriarchs and their bloodlines.

I think all of this rather undercuts John’s claim that we’re just dealing with Azzarello’s cynicism. Azzarello is cynical…but it’s a cynicism of violence and male prerogative. What’s real in Azzarello’s world is power and patriarchy. Contra John, that’s an ideological position, not a neutral one; contra Charles, it has little to do with upending hegemony. Instead, it’s just the usual male genre bullshit, executed with just enough skill to be considered competent by the standards of contemporary mainstream comics. If it wasn’t about Wonder Woman, nobody would give a crap. As it is, Azzarello and Chiang are working on a character that someone else once actually invested some genius in, and so they get to bask in the wan glow of banal desecration. Good for them. No doubt Azzarello’s Comedian will be similarly daring. It’s a career, I guess.