(This article is the third in a series on Tsuge Yoshiharu. The two previous articles may be found in here and here)

“Tsuge tries…to grope for images that will enable him to reach the umbilicus of his uncertain existence. … He became a symbol of youth culture and also counter-culture…” (Tsurumi 1987: 417)

“Yoshiharu Tsuge stands among the giants of the world of comics.” (Randall 2003: 135)

“In the history of Japanese comics, Tsuge has his place on top of the mountain.” (Marechal 2005: 28).

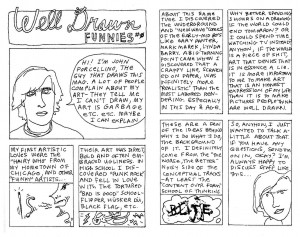

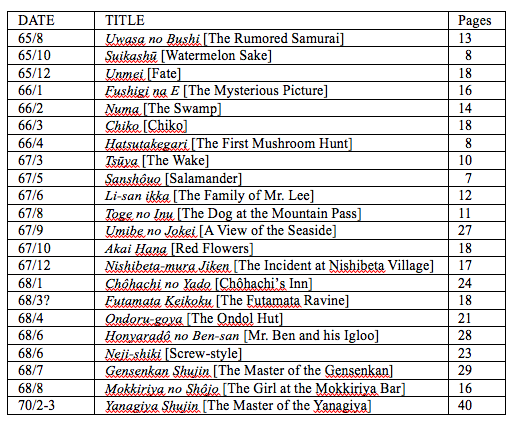

As these quotations show, Tsuge Yoshiharui is widely recognized as one of the truly great manga artists. At least two critics (Yamane 1983, Marechal 2005) specifically place him alongside Tezuka Osamu as one of the ‘twin peaks’ of the modern manga landscape.ii Yet very little of Tsuge’s work has been translated, largely due to the reclusive character of the author, and he remains under-researched and little understood in the English-language world. In two previous papers for IJOCA (Gill 2011a, Gill 2011b) I have discussed some of Tsuge’s seminal works from his golden period of 1966-68 for the underground magazine Garo. In this series of papers for IJOCA, I have attempted to make a start on filling the void in English-language Tsuge criticism. The first paper introduced some of the key Tsuge themes – alienation, madness, spiritual freedom, city-dwellers adrift in the country – through an analysis of a single manga, Nishibeta-mura Jiken (‘The Incident at Nishibeta Village’, December 1967).’ The second compared the treatment of the motif of an abandoned fetus in Tsuge’s Sanshouo (‘Salamander’, May 1967) with several manga by Tsuge’s contemporary, Tatsumi Yoshihiro. In this paper I propose to focus on Tsuge’s brilliant exploitation of the range of literary and visual techniques available only to the manga artist, by taking a close look at three more of Tsuge’s finest manga from his Garo period: Chiko (Chiko), Umibe no Jokei (A View of the Seaside) and Honyara-do no Ben-san (Mister Ben of the Igloo).iii They date respectively from 1966, 1967 and 1968. During these crucible years, Tsuge’s muse was developing so fast that it makes sense to describe these manga as representative of his early, middle and late Garo periods, although they were all written within a period of two years. Since none of these manga have ever been translated,iv I will give a brief plot summary of each before proceeding to discuss the way literary and visual narratives play off each other in each of the stories. I will also discuss the insights of Japanese critics, especially Shimizu Masashi, who to my mind is the most interesting of Japan’s numerous Tsuge scholars.

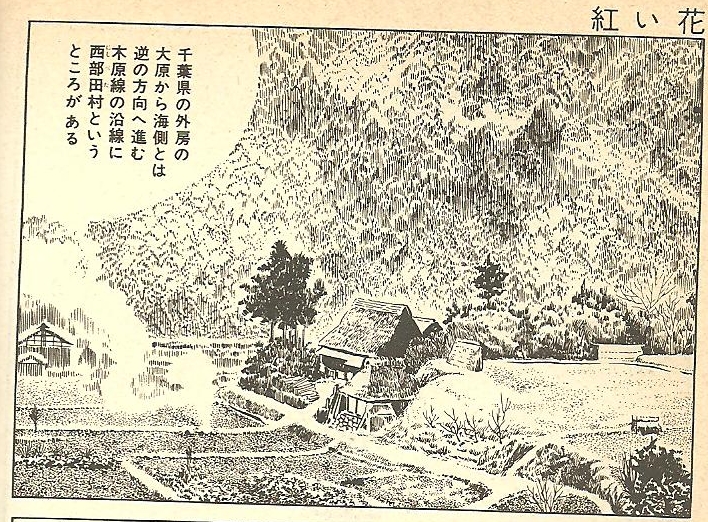

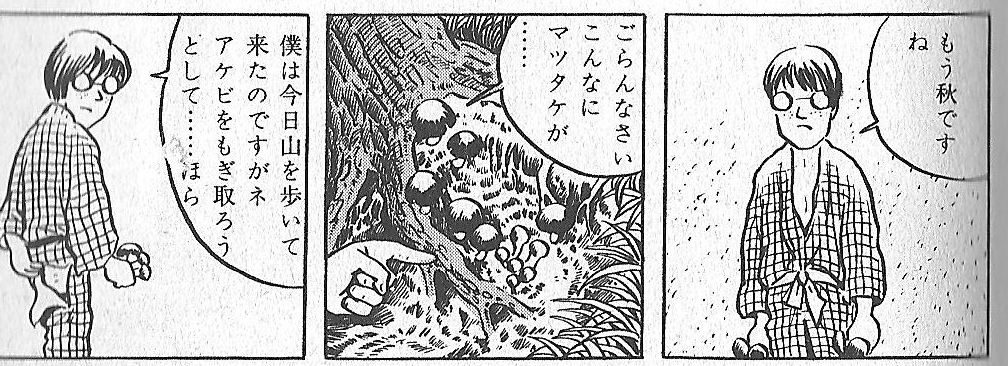

‘Chiko’ (Garo, March 1966, 18 pages)

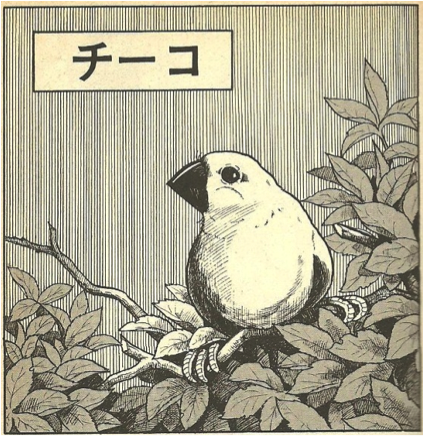

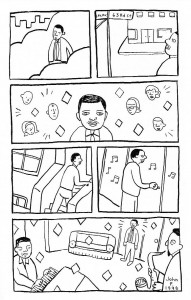

Figure 1: ‘Chiko’, opening frame

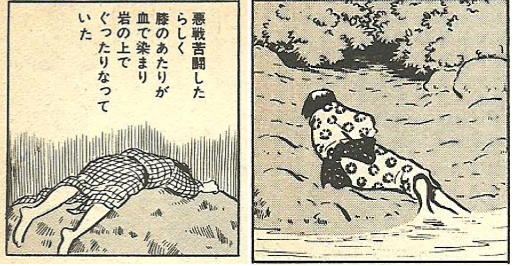

The second of Tsuge’s great Garo manga,v this is one of several that is heavily autobiographical, and hence operates at one level as a reflection on the nature of the manga artist’s profession. It depicts a struggling manga artist living with his girlfriend. His career is stagnating, and she is working at a hostess bar to support both of them. She buys a baby Java sparrow (buncho) with pocket money she has saved by abstaining from playing pachinko. That night she fails to come home at the usual time. He waits at the station until the last train has come and gone, then returns home to find her lying collapsed in the hallway. She is totally drunk and has been out for a drive with a customer from the bar. This triggers an ugly row: he resents the fact that her work involves flirting with other men; she resents the fact that his lack of success forces her to do that kind of work in the first place.

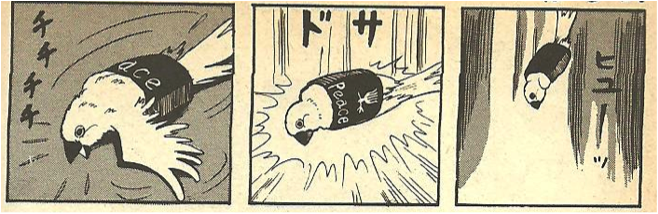

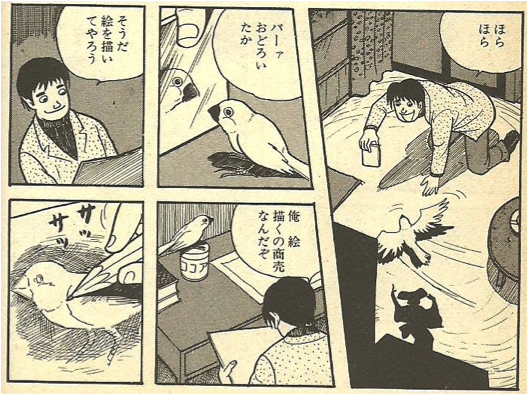

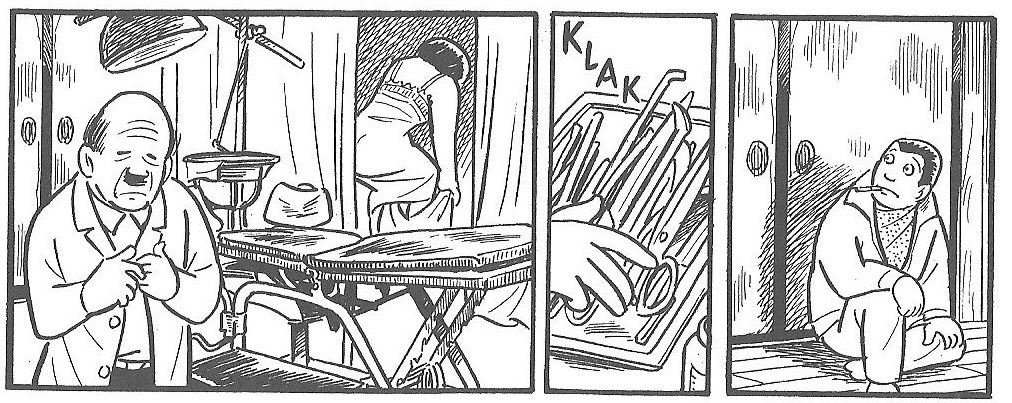

The dark atmosphere of the yarn is dispelled by the antics of Chiko. There is an unsignalled gap of a few weeks or months after page 10. Chiko has grown into a pretty bird who enjoys flying around the apartment. The girlfriend mentions that they have had far fewer fights since Chiko arrived. While she is out, the artist tries to draw a picture of Chiko, and he puts her little body in the sleeve of a cigarette box to keep her still while he draws. Then he playfully tosses the box into the air. Chiko manages to get out and fly to safety. Delighted, he tries to repeat the trick but this time Chiko fails to escape and is killed on impact with the floor after pathetically struggling for a few moments (figure 2). In a small but telling detail, the sparrow’s little red beak turns white before his eyes.

Figure 2: The Death of Chiko

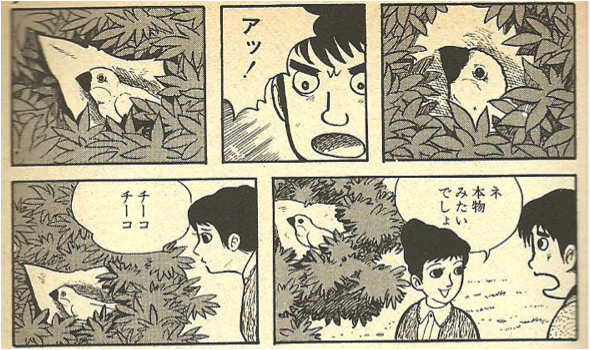

Deeply shocked, he buries Chiko in the garden and pins the picture he has just drawn of her on the doorpost. He lies to the girl that Chiko has escaped; she does not believe him. She accuses him of killing Chiko out of jealousy because she loves the little bird so much, gets a trowel and starts digging around in the garden. She announces she has found Chiko. In fact it is a strange, hysterical joke: she has put the picture he drew of Chiko in a bush so that it looks like the real thing. As they look at it, a gust of wind lifts it into the air and it appears to fly away as they look blankly up at it (figure 3). The End.

Figure 3: The picture in the bush

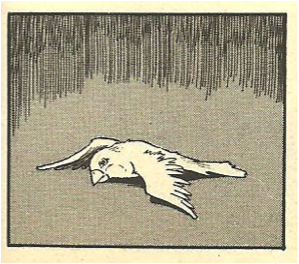

This is a symbolist fable, in which the sparrow seems to work on at least three levels. First, it symbolizes the girl. She twice refers to the fact that Chiko never tries to escape even if left by an open window. We wonder why she herself does not try to escape from the manga artist, who frequently addresses her rudely and fails to provide for her. When she does make a show of escape, she ends up dead drunk and collapsed on the floor. This scene is later visually echoed by the dying bird on the floor (figure 4).

Figure 4: ‘Chiko’ p. 8 bottom frames, p.14 frame 9

The death of the bird – thrown up in the air in a cigarette packet by the manga artist – results from a casual deprivation of freedom perhaps similar to that he has imposed on the girl. When its red beak turns white on death, that could symbolize the end of their affair: blood draining away equating to passion fading away. Chiko’s little red beak could even be read as a symbolic clitoris, as opposed to the phallic duck in Numa.

Secondly, the sparrow is a symbolic child. One might say that of all pet animals, but especially of this one. Shimizu points out that the wheedling way the girl talks about wanting to get the bird – “I’ve been wanting one for a while now… they become very attached to you if you raise them from chicks” etc., sounds almost as though she is talking about wanting a child, and he even experiments with rewriting the conversation so that she is telling him about an unexpected pregnancy rather than spotting some chicks in a pet-shop (Shimizu 2003: 31-2). He then reads the ensuing events as symbolically representing the abortion of a fetus. That is a speculative reading, but certainly the killing of the bird appears to be killing the relationship, whether you read it as symbolic abortion or infanticide.

Thirdly, like all caged birds, Chiko also represents the trapped human spirit. The story is saved from being unremittingly bleak by the final twist where the picture of Chiko appears to morph into the real thing and fly away in the final frame. The mysterious ending may not signify the saving of the relationship (the shocked/bewildered expressions on their faces tell us this is not such a simple happy ending), but perhaps it does remind us that the end of a relationship can bring freedom as well as loneliness.

Figure 5: ‘Chiko’, final frame (left); detail (right)

There is something very playful in this final image of an image of Chiko: is she really coming back to life, turning this into a magical fable? Or is it just a trick of the light? The bird certainly seems to be coming away from the paper, but it is still in the standing pose as drawn by the artist. It almost seems to be riding a magic carpet. There is of course a layer of ironic self-referentiality here as Inaga (1999: 125) points out: the ‘real’ Chiko is really just a drawing in a manga, which is itself about a manga artist, shown drawing it in the second frame, so at one level the closing frames constitute an intellectual joke at the expense of the reader.

And then Tsuge plays one more trick: though to get it, we have to return to the title page (figure 1). Here’s a charming study of Chiko, sitting on a little branch amid foliage, looking very perky indeed. And then we remember: this scene never happened. Chiko was taken from the pet shop as a fledgling, reared in captivity, and never flew out of the window. So what is she doing on this branch? Perhaps this story, like its predecessor (Numa, the Swampvi ), is readable as a loop, in which the first page leads on from the last, in which case Chiko really did come back to life, at least in the artist’s imagination, reminding us again that this is a manga within a manga, and inviting us to reflect on the artist as god on paper, even as he struggles with poverty and alienation outside the frames of his work. Yet another layer of self-referentiality comes from the fact that Chiko’s death follows her entrapment in a cigarette pack (the ‘Peace’ brand) which has a picture of a flying bird on it – the dove of peace. There is a sad irony in Chiko’s death, deprived of her ability to fly by a box with a flying bird depicted on it. She has been trapped by the artist, just as later, on the final page, she will be liberated.

In an interview with Gondo Shin, Tsuge comments about the time when he was writing Chiko: “I felt this sense of liberation from the story-driven, entertainment manga I had been drawing up till then… I think there was some sense of propriety inside me that said this was how manga have to be. That gave way to a feeling of liberation” (Tsuge and Gondo, 1993(2): 38). I would argue that the image of Chiko the sparrow, peeling away from the paper she is drawn on as she drifts into the sky, is an expression of that sense of liberation. It is not a simple achievement of happiness – a story in which the little bird came back to life bringing happiness to all would have been trite indeed – but that final image allows us to hope. Along with the opening image of Chiko, this is one of very few frames which are set outdoors and in daylight. Otherwise the story is set in an unremittingly claustrophobic interior and mostly at night. Note too that the opening and closing frames are by far the largest: most pages in Chiko have 7 to 11 little frames, but the 2/3 of a page devoted to the opening portrait of Chiko, followed by a cinematic half-page frame on p.2 taken from an elevated position in the manga artist’s room and showing him at work, draw us into the story while the whole page of the final scene brings closure/revelation. As Yomota argues, frame design is a device that distinguishes manga from film: variations in size and shape by the author, and the time taken over viewing each frame by the reader, create a unique communicative experience (Yomota 1994).

The rhythm of the frame sequencing is enhanced by some simple graphic techniques. Backgrounds are drawn in alternating shades of white and grey, with hatched shading used at dramatic or ominous junctures. Human figures are sometimes drawn in silhouette, notably the girl when she lies collapsed on the floor. A fairly conservative reliance on rectangular frames gives way to asymmetrical trapezoid frames at four crucial junctures in the story, disrupting the balance and perspective of the visual narrative. Figure 6 shows a good example. The playful antics of the manga artist as he waves a mirror to confuse Chiko are given an ominous tone by the trapezoidal frame and the black silhouette of the dancing doll in the foreground.

Figure 6: ‘Chiko,’ p.10 frames 6-10

Sound effects are faded in and out – with typical manga use of onomatopoeia, Tsuge lets us hear the sound of the bird chirping or the door opening when the girl comes home; but he leaves us in total silence as the crowds of commuters hurry out of the station. Again, the sparrow’s death rattle (kukuku) is the last sound effect in the story. Apart from one slight rustle in the bushes, there are no sound effects in the last four pages of the story – we never hear the digging of the grave, the return of the girlfriend, the opening and closing of the door, or the whistling of the wind that carries off the picture of Chiko. Except for a little dialog, Tsuge has silenced the soundtrack as his fable moves from social realism to magical realism.

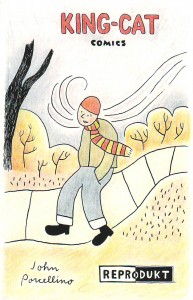

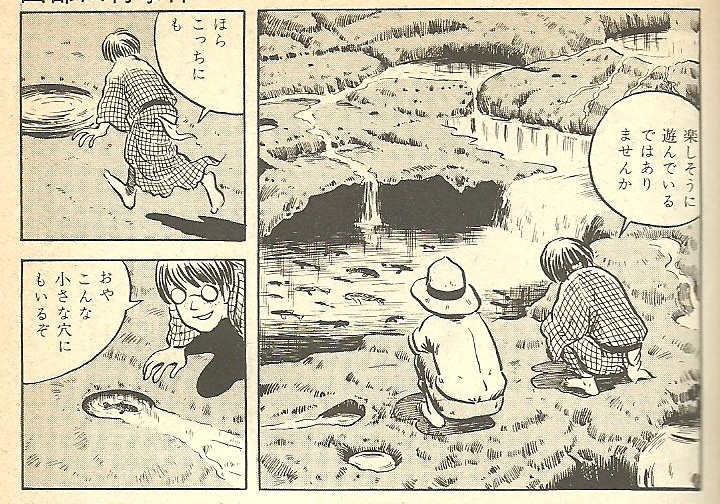

‘Umibe no Jokei’ [A Description of the Seaside] Garo September 1967; 27 pp

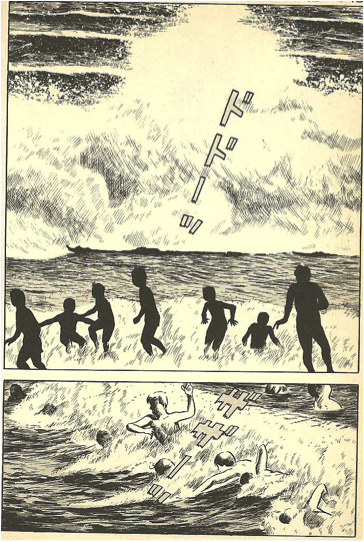

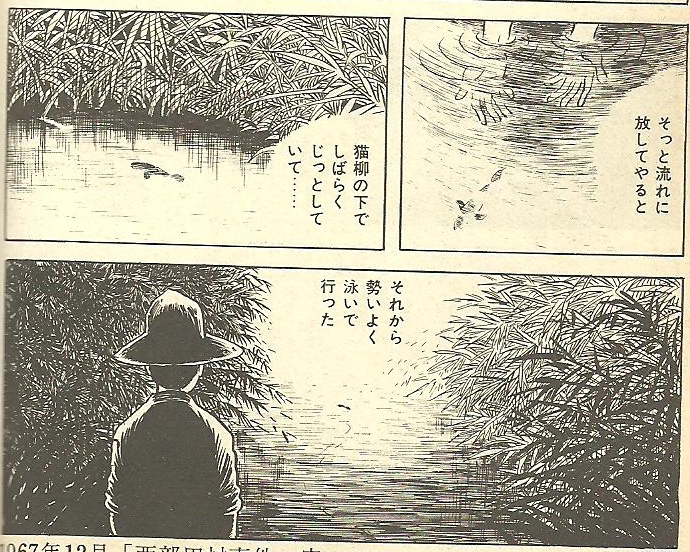

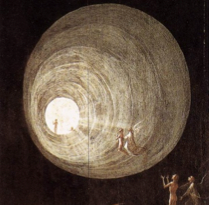

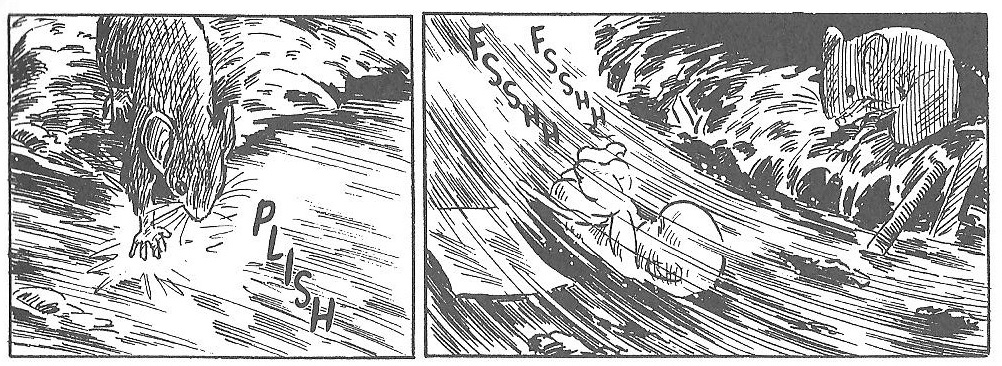

Visual and literary narratives pull in opposite directions in this story of a young man finding love on a solitary trip to the seaside. It opens with a 2/3 page frame of holidaymakers playing in the surf at a beach, seen in black silhouette while the surf crashes in. The second frame shows the swimmers in close-up, seeming to struggle desperately against the breakers, though they are supposed to playing (figure 7).

Figure 7: ‘A View of the Seaside’, page 1

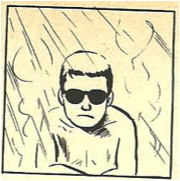

On page 2 another large frame shows parasols and sunbathers on the beach, one young man sitting separate from the others in the foreground. Two more frames pan in on him from behind (figure 8 top). Each shot is from a different angle, as though we were approaching the boy in a serpentine movement. On page 3 the camera has traversed and we see him from the front, sitting alone in dark glasses, smoking (figure 8 bottom). A pretty young girl in a bikini throws herself down on a towel nearby and looks at him. She seems interested in him. He shyly looks away and lights a cigarette.

Figure 8: ‘Seaside,’ p.2 frames 2 and 3 (top), p.3 frame 2 (bottom)

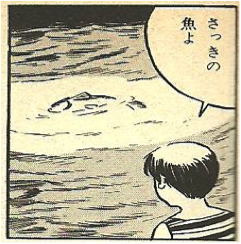

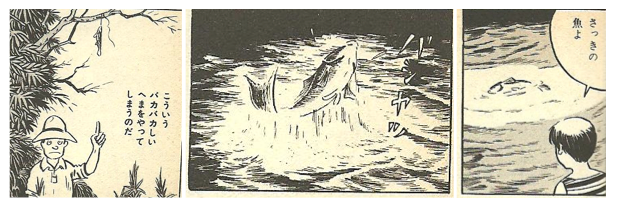

An older man comes over and warns her of sunburn. She asks him to rub olive oil into her back. Our hero is jealous and walks away. Blazing sun, steepling stratocumulus, black birds tossed across the sky Van Gogh style. He stands in front of a cove with crashing surf; huge cliff on far side. Senses a presence: finds the girl sitting on the other side of an outcrop in a hooped one-piece. As their eyes meet, a big fish leaps out of the sea, hooked on a line (figure 9). A fisherman standing on the cliff has caught it and hoists it up into the air, but the line snaps and the fish falls back. She wonders what kind of fish it is but he doesn’t know.

Figure 9 ‘Seaside’ p. 7 Frame 4

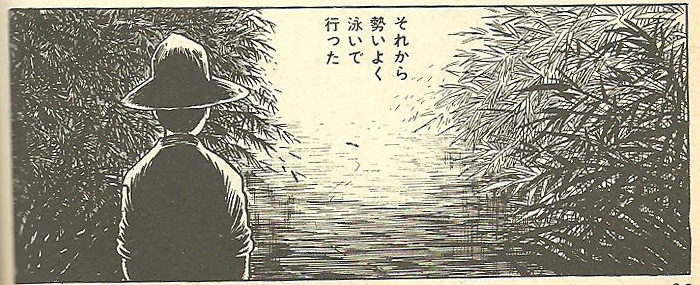

He lights a cigarette and she asks for one. They are shown in a big frame, silhouetted in front of the white surf and black cliff beyond. In conversation, she tells him that she is on her own – she says she enjoys travelling alone, but her eyes are wistful. It turns out they are both from Tokyo. He has been invited to the seaside by his grandmother – he is pale and unhealthy and needs to get some sunshine. He came reluctantly, “but I’m glad I came. I’m really glad.” He speaks in silhouette against a grey sky with a single bird flying across it. “It’s indescribably better than staying put in my gloomy apartment in Tokyo. If only this feeling would continue forever…”

He explains that his mother was born in this town and that he lived here himself for a year when he was small. He is now staying at his grandmother’s house, but doesn’t know the other people there – it’s been twenty years. She says she envies him having relatives in such a lovely place.

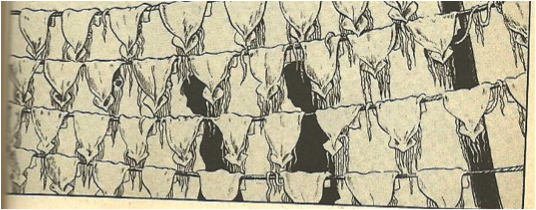

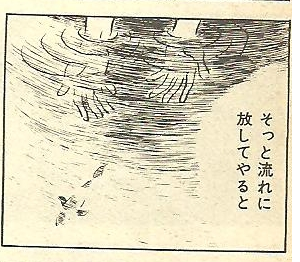

Walking along the foot of the cliff, they notice the fish – floating there dead. It must have been killed on impact when it hit the sea. He now recalls an incident from childhood – a drowning victim was found caught in the nets of a fishing boat over by the cape. The victim was totally white, with mouth and nostrils full of seaweed. “Do fishermen sometimes get drowned?” she nervously asks. “It was a woman, with a child,” he replies. “The child was half skeletonized. It was terrifying. There’s a nest of octopuses under that cape.” She thought octopuses were cute, but he tells her they are voracious predators – as one can see from their sharp beaks. While speaking, they pass a set of wooden frames with caught octopuses hung out to dry (figure 10) – some of these voracious predators at least have been defeated.

Figure 10: ‘Seaside’ p. 13 frame 5

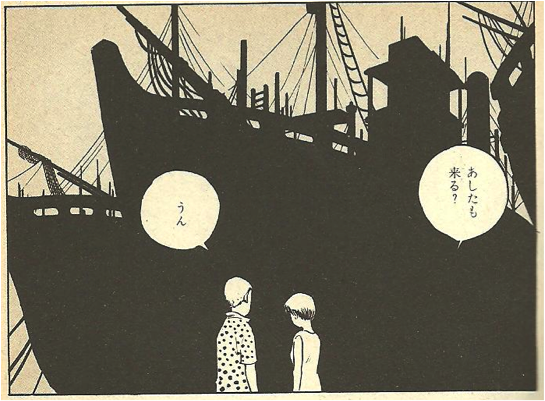

Standing in front of two vast silhouetted fishing boats (figure 11), she asks if he will come to the beach again tomorrow. He says yes, probably just after lunchtime. They part at a beached rowing boat. These two frames take up a whole page. The story is moving more slowly, more cinematically, than ‘Chiko.’ Where ‘Chiko’ had 142 frames in 18 pages, this story has 116 frames in 26 pages; 4.5 frames a page, against nearly eight for Chiko.

Figure 11: ‘Seaside’ p.13 frame 1

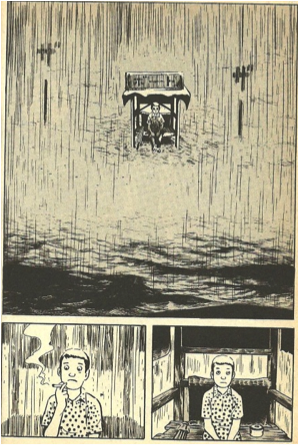

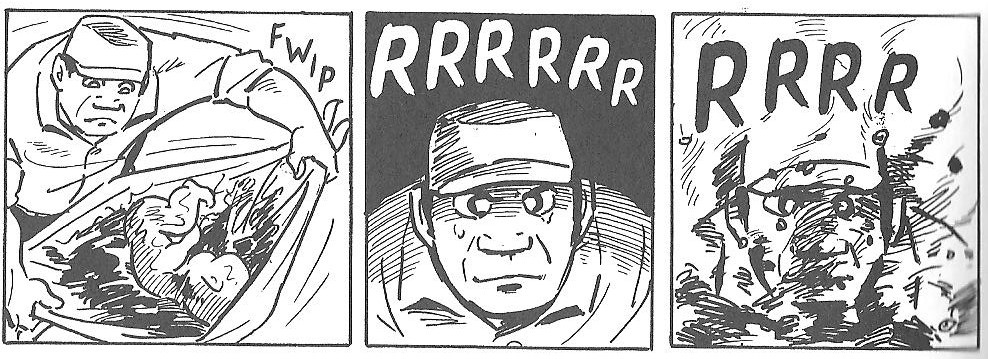

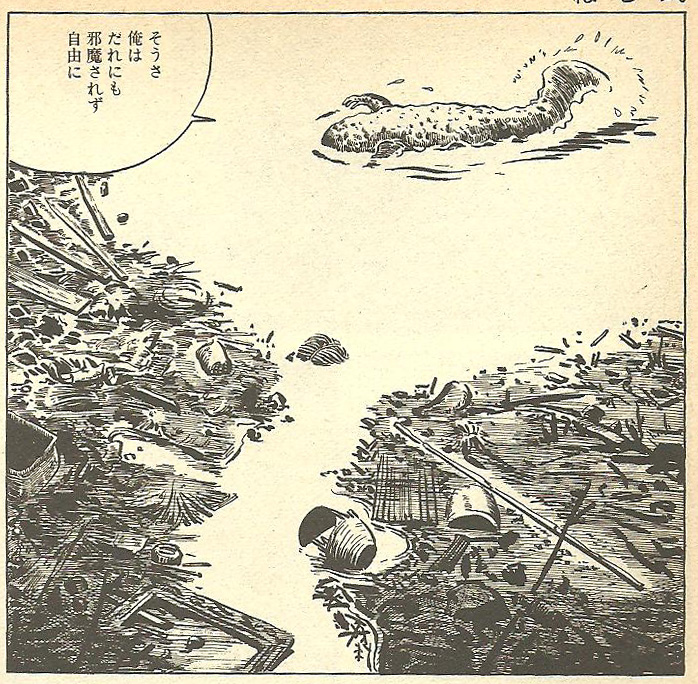

The next day, rain is crashing down on the beach. Hero is sitting alone in the shelter of a small hut for boat hire, smoking (figure 12). He tosses the butt into the sea, then lobs a couple of pebbles at a flock of seagulls gathered in the water just off the coast. They fly up, in black silhouette. He is about to give up waiting and go home, when the girl comes running in a tiger-stripe one-piece, a towel over her head. She is sorry she is late – she has been working. He correctly guesses that she is a fashion designer. How did he guess? “The dress you’re wearing now shows very good sense.” “It’s just a towel,” she says, slipping a strap off the shoulder. The pace of the narrative is picking up – we are briefly up to eight frames a page.

Figure 12: ‘Seaside,’ p.15 (top); detail (bottom)

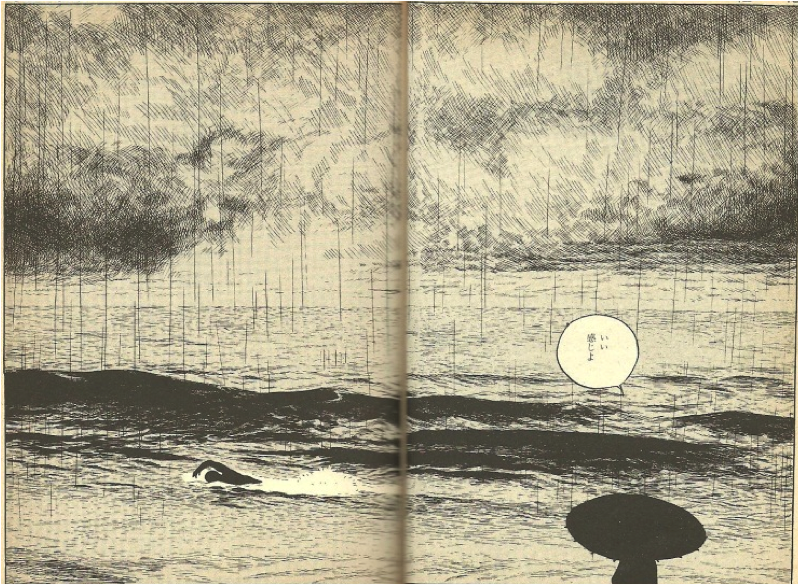

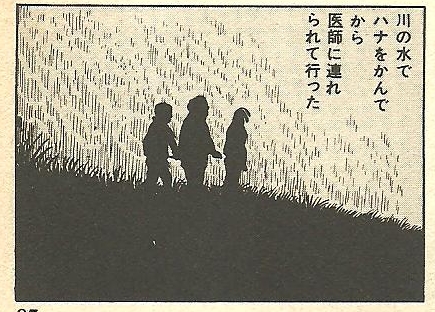

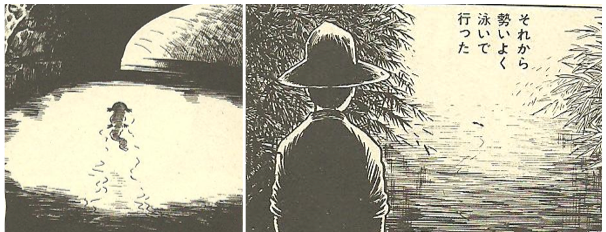

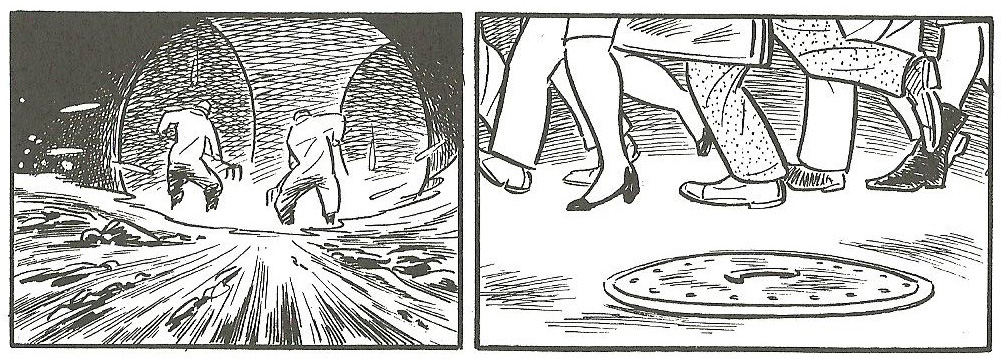

They sit down together in the boat-hire hut. “There’s nobody here at all,” he observes. “Nice and quiet this way,” she replies. He offers her some honey beansvii he has sneaked from his aunt’s house. She enjoys a spoonful, then says she is going to go swimming in the rain. She strips off to reveal a new bikini; he says it suits her incredibly well. Their eyes meet significantly. “You’re a nice guy” (anata ii hito ne) she says. They run into the sea together, silhouetted and with lots of black gulls above them. She admires his swimming style – now the gulls are all white. He proudly tells her he got a first-class swimming certificate when still in junior high school. But he confesses he has lost strength since then – and indeed, he is puffing and panting now. She notices that he is unhealthily thin and his lips have gone blue. She suggests they should get out. He is about to agree, but changes his mind – since she has praised his swimming, he will do some more.

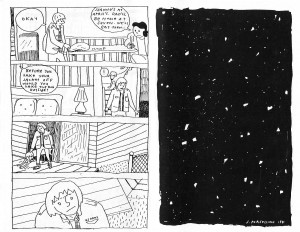

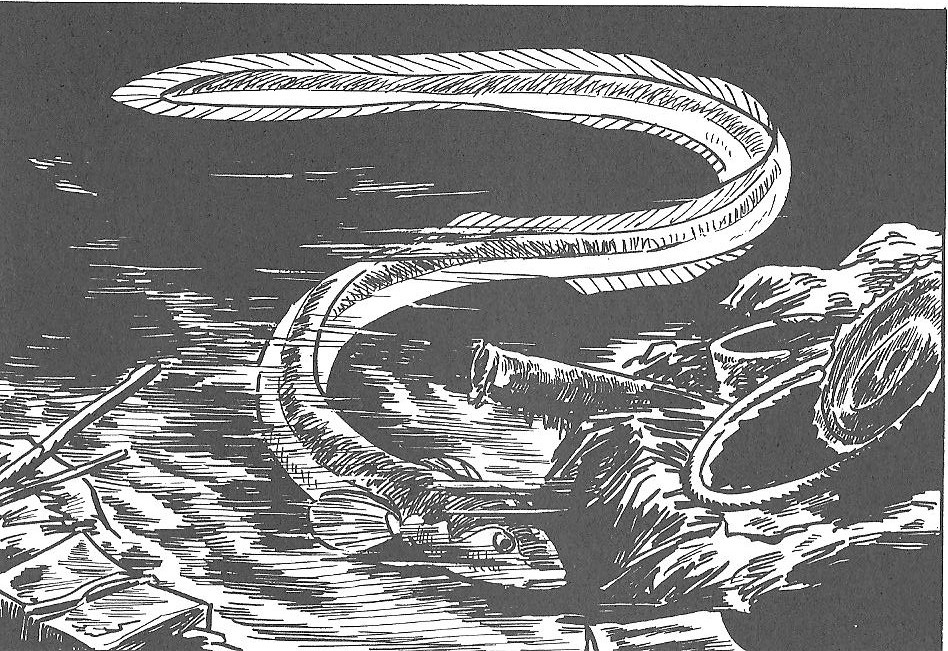

He starts swimming back and forth amid the dark, swollen breakers, while she retreats to the shore and watches from under a traditional lacquered paper umbrella. He is breathing heavily, totally absorbed in the swimming. She looks on in a half-page frame, saying “you are lovely” (anata suteki yo). The final frame (figure 13) goes over two whole pages and is one of Tsuge’s most famous images. Hero is still swimming, and she is standing under her umbrella saying “feels good” (ii kanji yo). Both of them are black silhouettes, like cut-out holes disrupting the otherwise photographic zero-point perspective of the image. The camera has pulled back from the previous frame, revealing a hazy horizon, vast banks of bulging clouds, and rain coming down like needles. It is a fittingly cinematic conclusion, and prompts Takeuchi Osamu to discuss it at some length (Takeuchi 2005: 76-82) as an exemplar of what he calls “the narrator of perspective” (shiten no katarite).viiiWhen the protagonists are conversing, the camera is positioned fairly conventionally, close up and just a little above the speaker’s face. But at intervals the camera pulls out, and the narrator of perspective takes over. In these frames either the characters are silhouetted or the landscape is blacked out. The former effect foregrounds the characters; the latter brings the landscape closer and reduces the characters to anonymous ciphers. The net result is to “alienate reality” (genjitsu o kairi saseru) (ibid.81).

Figure 13: ‘Seaside,’ last frame

On the face of it, things seem to have gone very well for our shy and awkward hero – an attractive girl is consistently positive towards him and we might even expect a conventional romantic conclusion. But the relentlessly dark tones of the drawing, and the disturbing imagery of the dead fish, drowned woman, vicious octopuses etc., lead the reader to expect the worst – perhaps the hero’s exertions in attempting to impress her with his swimming will lead to his own drowning. As he dives into the water, his form clearly recalls the dead fish (figure 14). In the end, we get neither the romantic nor the tragic conclusion: instead, the story ends with an upbeat, romantic last line and a dark, foreboding image. Both expectations and fears are left unrequited.

Figure 14: ‘Seaside’ p.12 frame 1, p.23 frame 5.

Shimizu (2003: 413-414) offers a daringly Freudian reading. For him, this is an oedipal fable, the man wanting to return to the womb / eternal mother = the sea. The fish leaps up in the air at the moment our hero catches sight of the girl – a phallic moment. But then we see it is not leaping but caught – hoisted into the air and then dropped to die on impact with the sea.ix Shimizu sees this as a metaphor for the young man, the fisherman being his father-figure. The girl is a siren, luring him back to the sea / death. On the second day, when he appears sitting in the boat-rental hut with the rain pouring down, he is already dead. As evidence, Shimizu points out that behind his head are two diagonal black lines, resembling the black ribbons at the top corners of a dead person’s photo at a funeral (figure 12 bottom). In the next frame, the diagonal lines have mysteriously disappeared, but he has a small pot next to him (figure 12 top, frame 2). In plot terms it contains the honey beans that he will share with the girl, but in symbolic terms, Shimizu argues, it contains his own ashes.

Tsuge’s fables are more ambiguous than Shimizu’s intermittently brilliant commentaries on them allow. There are plenty of sinister characters in his works, but the girl in ‘Seaside’ is sweet and innocent. She is scared of octopuses and tries to persuade our hero to leave the dangerous cold waters of the sea. She is not a plausible siren. But we do not have to accept the whole of Shimizu’s radical interpretation to appreciate the sinister effect on the atmosphere of the story from the visual devices that he identifies. ‘A View of the Seaside’ is a classic example of Tsuge’s brilliant use of the manga medium: the visual narrative, with its huge brooding cliffs, sinuous black waves and silhouetted hulks of ships, creates a constant undertow pulling against the tentatively optimistic verbal narrative.

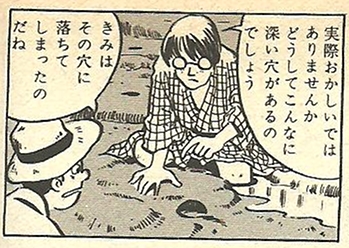

‘Honyarado no Ben-san’ [Mr. Ben of the Igloo]. Garo, June 1968, 28 pages

Tsuge published this story in a special issue of Garo devoted to his work, along with ‘Neji-shiki’ (‘Screw-style’), his most famous work and one of the few available in a good English translation (Tsuge 2003). Though ‘Mr. Ben’ is a sad story, it does not have quite the doomed atmosphere of the other two, and it lacks their sexual tensions, focusing instead on the relationship between the artist/narrator and the intriguing man who becomes his host.

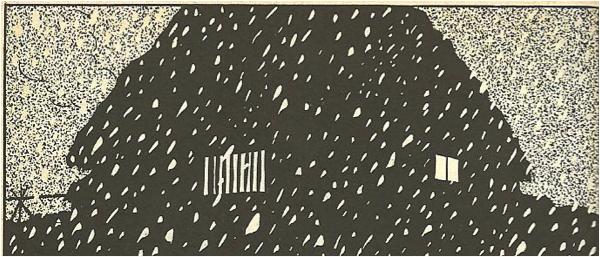

Figure 15 ‘Mr. Ben,’ first frame

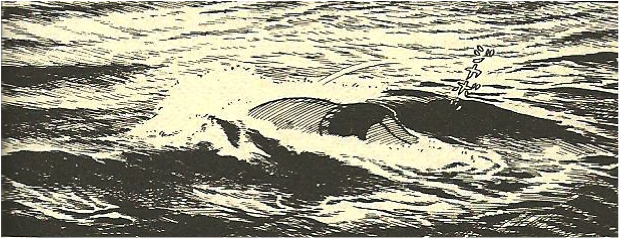

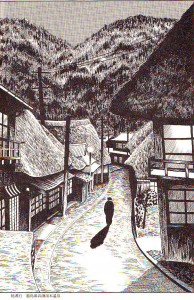

In the hamlets around Uonuma county in Echigo (Niigata prefecture), they have a custom called Torioi (Chasing off birds), held at Koshogatsu (Little New Year, Jan 14-15), in which the local children build igloos, called honyarado, and then spend the night sleeping in them (figure 15).They wear straw hoods, carry lanterns, and sing a song telling the birds to fly off back to Shinano (neighboring Nagano prefecture in today’s Japan). It is supposed to promote a good harvest in the coming year, by chasing away birds that might otherwise eat seeds, grain etc.

Figure 16 ‘Mr. Ben,’ p. 2 frame 4

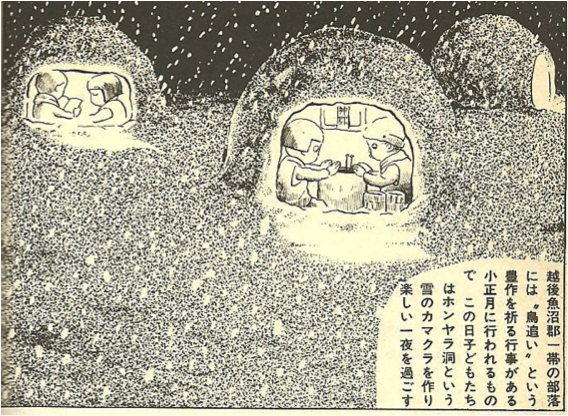

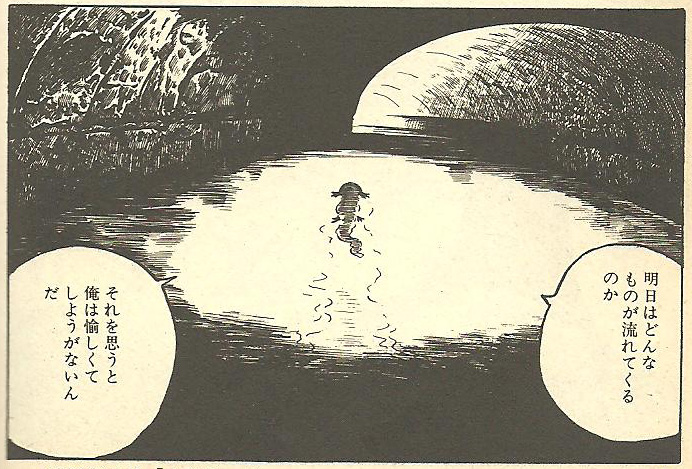

Our hero, a struggling manga artist on a solitary journey in quest of inspiration, arrives at Ben’s inn, on the outskirts of the village. Ben has not bothered to sweep the snow off his roof, so the inn resembles a giant igloo. Hero finds Ben lugubriously drinking alone (figure 16). He is Ben’s first guest for six months. They discuss hero’s inability to sell his work. Both men appear to be failing in their respective professions. Hero asks for dinner, but all Ben has is some grilled goldfish that he admits he stole from the neighboring village, where they are farming them. With that he falls asleep – hero has to rouse him to obtain a futon. Ben asks hero why he is traveling in such remote parts so soon after New Year, and suggests he must be lonely. Hero insists he just likes traveling and staying at inns like this one. Old pendulum clock shows 10.10 as they drift to sleep.

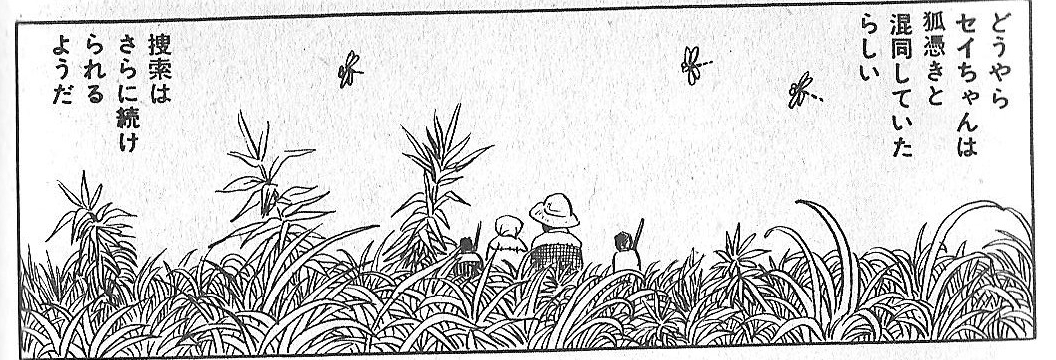

Next morning Ben catches a lot of dace, by banging on the ice with his mallet – the reverberations stun the fish and they float to the surface where he catches them in a net. He has placed a brazier in the toilet among various efforts to make the accommodation more comfortable. He has a pet rabbit called Pyon-chan in a cage with its name written on it. Ben is enlivened because he thinks hero will stay a few nights, but as Ben heads off to buy food, hero tells him he is not planning to stay any longer. He can’t afford it. Ben persuades him to stay and draw some manga. Hero says he needs a theme. For instance, the oddity of the rabbit with its cute name in an old man’s inn – there must have been children here lately. The inn is too big for a single man to run. Taken aback, Ben grumpily remarks “manga aren’t what they used to be.” Hero has sensed Ben’s wrecked marriage. Hero cheers Ben up by saying he might as well lay in a pen and some paper during his shopping.

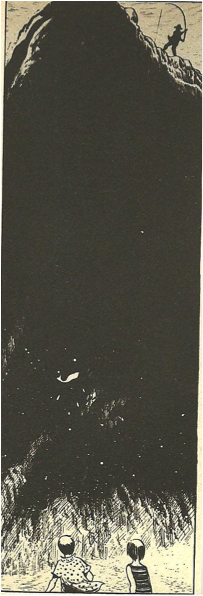

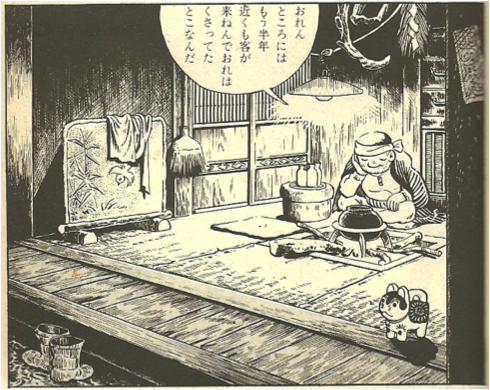

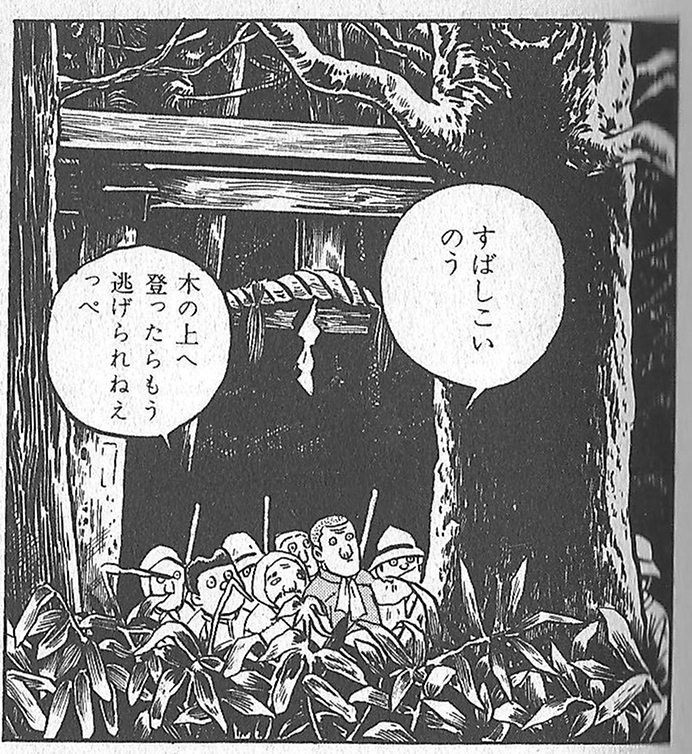

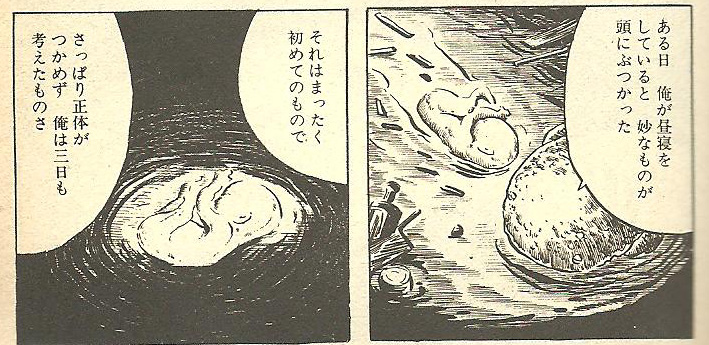

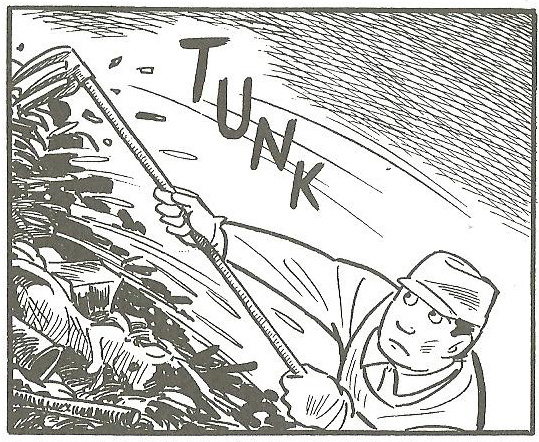

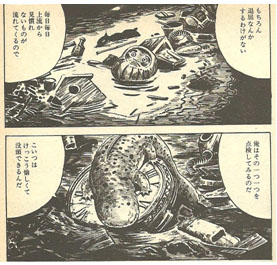

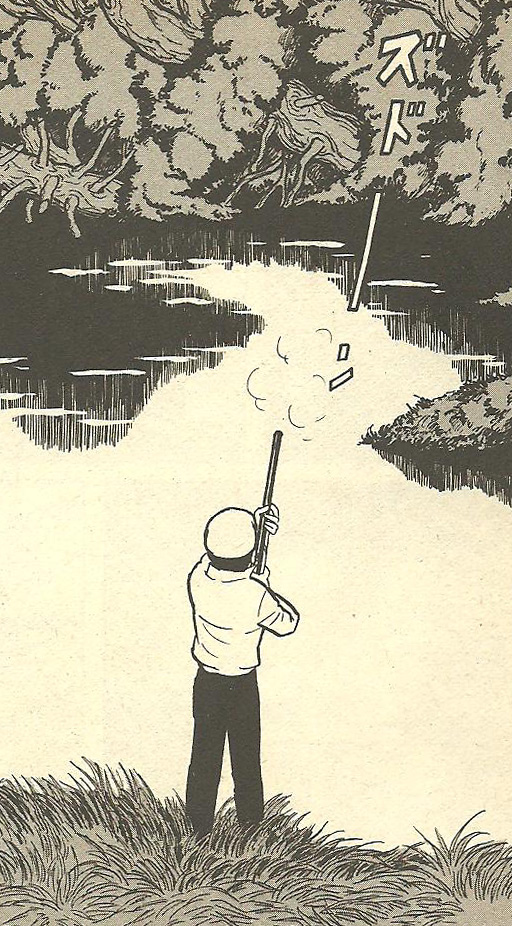

Figure 17; ‘Mr. Ben’ p. 18 frame 1

Night falls; Ben is back from the shops. Snow falling; clock ticking. Hero cannot think of manga idea. He will have to go home tomorrow. Ben suddenly resolves to go out and steal some more goldfish. Hero goes with him. Strong images of their figures struggling through snowbound countryside (figure 17). It is four miles to the neighboring village. Ben nets a beautiful golden carp in a pond there which he says is probably for export and worth about 100,000 yen – over $1,000. He is caught in the act by his daughter, a little girl in a straw hood, who is waiting for her friends to show up for the torioi. Ben asks after her mother. The girl says ‘nanmyohorengekyo’, a sutra, indicating that mother is a Nichiren Buddhist, possibly a member of Soka Gakkai.x Ben makes his daughter swear that she will tell nobody that she saw him here. Her friends arrive; she runs to join them; all are wearing straw hoods that make them look like birds. They chant the traditional lines and knock wooden blocks together to make the birds leave the crops alone (figure 17).

Figure 18 ‘Mr. Ben’ p.21 frame 3

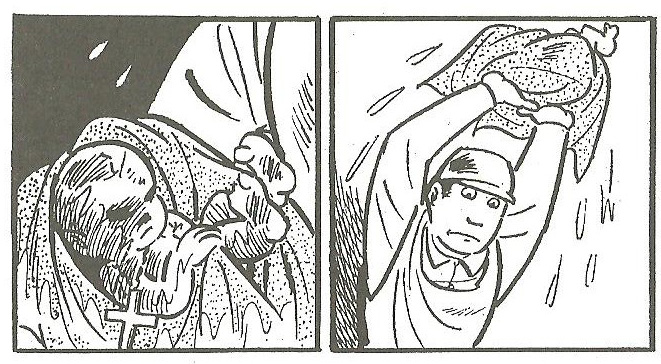

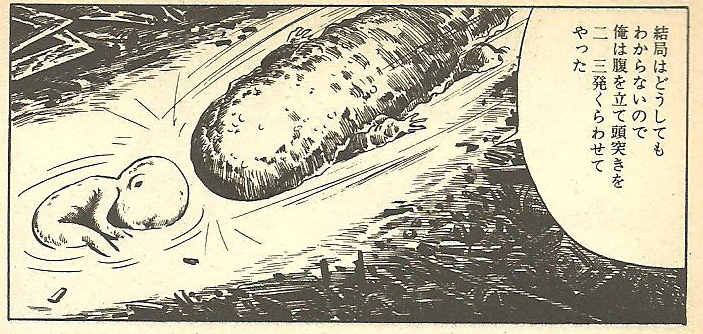

Ben and hero complete their escape with the carp. Ben explains that his wife thinks the success of her fish-farming enterprise is due to her sincere religious belief. He wonders maliciously how she will account for the disappearance of her prize carp despite all her sutras. When they get home, Ben plans to throw the carp into his own pond, so that he can look at it every day and say “serves you right” to his wife. But when hero takes it out of the net, it is frozen solid with its back bent. It has been a three hour walk home through intense cold. Ben is deeply shocked. They take it indoors, thaw it out and eat it for sashimi instead.

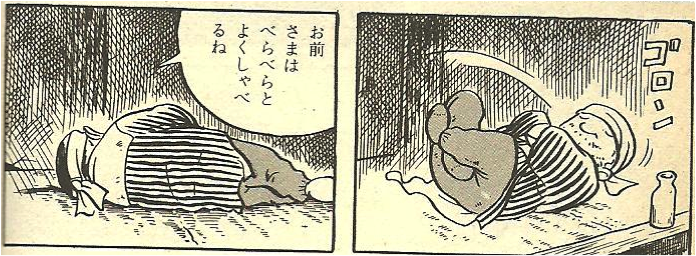

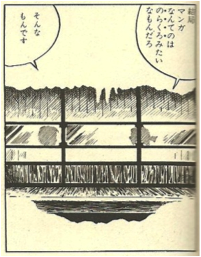

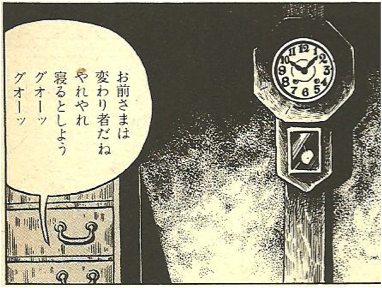

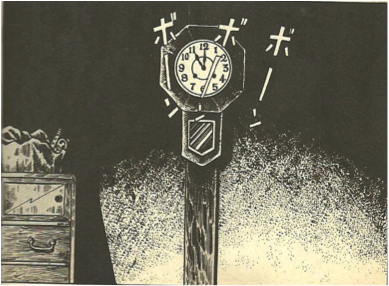

Last two pages. Hero and Ben drinking saké at the hearth. Hero asks: “In the end, what were we really doing in the snow?” (Ben empties saké cup). Hero continues: “If someone looked at us like items added to a landscape, in the final analysis what general meaning would it convey?” Still getting no reply, he asks, “Old man, how do you find the taste of a 100,000 yen carp?” Ben merely rolls over to go to sleep, aying “how you do go on – blah, blah, blah (bera-bera)…” (figure 19). The clock starts striking eleven, bon, bon, bon, seen on its own in dark shadow in the final frame. In a comic that makes very little use of sound effects, the clock is the loudest thing in the house: silent when first observed on page 6, its accentuated ticking (katchi-katchi) dominates page 15, and its funereal chimes on page 27 bring the story to a lonely conclusion.

Figure 19 ‘Mr. Ben’ p. 27 frames 2, 3

Once again, the story ends on an enigmatic note, challenging the reader to decipher it. In the closing pages the reader merges with the manga artist in the story, wondering what on earth the two men have been playing at and fearing that his own interpretation could be no more than the “blah blah” cynically dismissed by Ben.

The first clue is in the title – Mr. Ben of the igloo. It focuses on the relationship between the man and his house. It is a cold and empty house – his family is gone. The house is a macrocosm of the man. With its thatched roof it physically resembles Mr. Ben when wearing his straw coolie hat. When Ben is happy because of the arrival of our hero, the snow is piled up in front of the house in a way that resembles a smile (figure 20 left). In its final exterior shot (figure 20 right), where light pours from two eye-like windows beneath the thatched roof, the snow falling before it suggests lonely tears.

Figure 20 ‘Mr. Ben,’ p. 12 frame12, p.27 frame 1

His solitary igloo is counterpoised to the cozy domesticity of the children sitting in couples in the cluster of igloos in the opening image of the story (figure 15). Shimizu, determined Freudian, also finds a hint of sexual bliss in the image of the little children sitting in boy-girl pairs in their igloos – or maybe the igloos are like little wombs (Shimizu 2003: 134). Later he also describes Ben’s inn as a kind of womb, warm and moist against the cold dry air outside. Ben several times rolls up in a fetal position (figure 19) – he is returning to the womb, and he doesn’t really want to wake up from his frequent drunken stupors (ibid. 164). When we first see Ben (figure 16) he is sitting apathetically in a homely room bathed in warmth and light and dotted with symbols of domesticity – a broom, a ceramic cat, a wooden screen with some clothing hung over it, the hearth, the cooking pot. But by the hearth is an empty cushion – in the position where, as Shimizu points out, we would expect his wife to sit (ibid. 136).

As the yarn unfolds, the sad tale of Mr. Ben’s failed marriage is gradually revealed. The marriage seems to have foundered on religious differences. His wife’s obsession with her religion has taken her and the daughter away from Ben, who is deeply skeptical. She has gone back to her family, who share the same religion and the same obsession with fish farming. These farmed fish are counterpoised to the wild fish that are symbols of freedom in other Tsuge manga such as ‘The Incident at Nishibeta Village’ and ‘A View of the Seaside.’ Ben’s four-mile journeys to the neighboring village to steal carp may well be prompted not only by resentment against his wife and her family, but also by the possibility of catching a glimpse of his daughter.

We may guess that the break-up was fairly recent – the rabbit with its childish name is still alive and well. Perhaps the half year since Ben last had a customer corresponds to the time since his wife went back to her folks.

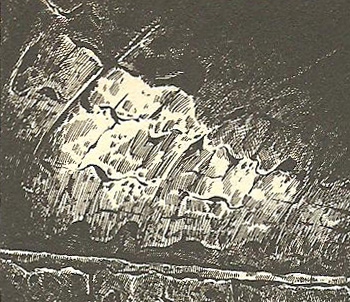

Once again the final frame (figure 21 bottom) is laden with significance. Shimizu points out a subtle touch: though the chest of drawers next to the clock is shrouded in darkness, we can just about make out a basket, with a small flute and the head of a kokeshi doll protruding from it (ibid. 163). These are no doubt things that Ben’s little daughter used to play with, and they bring a very lonely note to the ending. This chest has already appeared 20 pages earlier (figure 21 top) but there the top of it was deliberately concealed by a talk bubble, so we did not see the reminder of lost domesticity (ibid. 164). In another brilliant use of the manga medium’s potential, Tsuge draws attention to the little basket by concealing it and then revealing it with a device not available to any novelist, painter or film director. One can only nod in agreement when Shimizu admires the skilful use of these subtle devices in Tsuge’s work (ibid.).

Figure 21: ‘Mr. Ben’ p.6 frame 5 and p.27 final frame

Here, however, the acutely observant Shimizu makes an uncharacteristic error. On close inspection the object next to the flute in the final frame proves to be not a doll but a little drum with a handle and two tear-shaped black decorations. This is also a traditional child’s toy, but one more likely to be associated with a boy. This opens up a way for us to get deeper into the hidden back story of Mister Ben than even Shimizu has managed. I would suggest that in fact Mister Ben had two children, a boy and a girl, of which the boy has died. Likely it was the boy’s death that prompted his wife’s departure and increasing obsession with religion; maybe she blamed Ben’s impiety for a greater misfortune than just the decline of their inn-keeping business.

This interpretation, admittedly speculative, could account for Ben’s bizarre behavior with the stolen carp. He apparently thought it would still be alive after the three-hour journey home, since he proposed to throw it into his own pond. When it turns out that the carp is frozen stiff, he reacts in horror, and stands there cradling it in silence for two frames (figure 22), though to most people there is nothing obviously more shocking about a frozen dead carp than a limp dead carp. Perhaps the carp is a symbolic substitute for the dead boy… and Ben is totally unhinged. Once it is discovered that the carp is frozen stiff, Ben and hero thaw it out and eat it for supper, a fairly sensible thing to do in normal circumstances but deeply shocking if we take the fish as a symbolic equivalent of his son. No wonder Ben is plunged into total silence as hero asks him lots of questions about the meaning of the day’s events. We sense there is a great secret hidden behind his silence… I suggest that the two toys in the final frame represent two children, hinting at a deeper tragedy than the break-up of Mr. Ben’s family.

Figure 22 ‘Mr. Ben’ p. 25 frames 5, 6

There are a few more strands to the sadness of Mister Ben. First, the story is woven around the Torioi festival, designed to expel harmful pests from the village community.xi Ironically, Ben’s carp thievery means that he himself is now just such a harmful pest. When his daughter joins with her little friends to chant the ritual words of the Torioi festival, she is symbolically expelling her own father from the community. And second, there are times when a certain camaraderie seems to develop between Ben and the traveler, raising the possibility of male friendship as an alternative source of emotional warmth in the igloo. But that hope is dashed in the final frames, when the traveler tries to intellectualize their experience of the night, but Ben just complains about too much talk. He never even formally admits that the girl is his daughter, that his wife has left him, or anything else about his personal circumstances. Rather than opening up to the traveler, he rolls over, in a posture that could resemble a fetus, or maybe a frozen carp, and goes to sleep, next to his probably emptied sake bottle.

Conclusion

All three of these manga turn out to revolve around abnormal emotional states. The destructive relationship in ‘Chiko’ crystallizes around the little bird, functioning in a slightly similar way to the wild duck in Ibsen’s play of that title. Indeed the brooding atmosphere of this story and its sister piece, ‘Numa,’ which also features a duck wounded by a hunter’s shot, often recall the great Norwegian playwright. The woman’s game with the picture of Chiko is an act of madness. The young man in ‘Seaside’ appears to be risking death in a desperate bid to impress the young woman. Mister Ben has rejected society and is losing the will to live. Each of the stories also features a dyadic central relationship, and leaves us to ponder the state of the other partner: when the manga artist sees the image of Chiko fly into the sky, has he too been drawn into madness? Is the pretty young woman in Seaside an innocent, a siren, or both? And what of the artist in ‘Mister Ben,’ lost in the snow, struggling to make sense of his own actions?

Visually, the association between people and animals – a Java sparrow, a hooked sea fish and a frozen farmed carp in the three stories discussed here – is central to the symbolic system throughout. The line between humans making willed, conscious decisions, and animals governed by brute instinct and vulnerable at all times, is deliberately blurred, with ominous implications for the protagonists. The subtle variation in shape, size and shading of frames creates a distinctive narrative rhythm which is further refined by silhouetting and the use/non-use of sound-effects. Subtle changes in perspective and focus leave the reader unsettled and occasionally staring at frames that are works of art in their own right. Where some see comics as an inferior creative medium, literature not good enough to work without pictures, these works of Tsuge’s constantly remind us that in the hands of a master, this is a medium that can surpass the limitations of both art and literature, creating something truly new.

References

Gill 2011a. ‘The Incident at Nishibeta Village: A Classic Manga by Yoshiharu Tsuge from the Garo Years.’ In International Journal of Comic Art 13(1): 475-489.

Gill, Tom. 2011b. ‘Fetuses in the Sewer: A Comparative Study of Classic 1960s Manga by Tatsumi Yoshihiro and Tsuge Yoshiharu.’ In International Journal of Comic Art 13(2): 325-343.

Inaga, Shigemi. 1999. ‘Images of an Oriental Artist in European Literature.’ In Text and Visuality: Word and Image Interactions 3:117-126.

Marechal, Beatrice. 2005. “On Top of the Mountain: The Influential Manga of Yoshiharu Tsuge.” In The Comics Journal, Special Edition: 22-28.

Randall, Bill. 2003. Introduction to his translation of Tsuge’s “Screw-style” in The Comics Journal, vol. 250: 135.

Shimizu, Masashi. 2003. Tsuge Yoshiharu o yome (Read Yoshiharu Tsuge!). Tokyo: Choreisha.

Takeuchi, Osamu. 2005. Manga hyogengaku nyumon (An introduction to manga expressionism). Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo.

Tsuge, Yoshiharu. 1994a. Akai Hana (Red Flowers). Tokyo: Shogakukan.

Tsuge, Yoshiharu. 1994b. Neji-shiki (Screw-style). Tokyo: Shogakukan.

Tsuge, Yoshiharu. 2003. ‘Screw-Style’ (translation of ‘Neji-shiki,’ 1968). In The Comics Journal #250. Seattle: Fantagraphics; 136-157.

Tsuge, Yoshiharu and Shin Gondo. 1993. Tsuge Yoshiharu Manga-jutsu (The Manga Art of Yoshiharu Tsuge). Tokyo: Wise Shuppan. 2 volumes.

Tsurumi, Shunsuke. 1987. A Cultural History of Postwar Japan 1945-1980. London: Routledge.

Yamane, Sadao. 1983. Tezuka Osamu to Tsuge Yoshiharu: Gendai Manga no Shuppatsu-ten (Osamu Tezuka and Yoshiharu Tsuge: The Starting Point of Modern Manga.) Tokyo: Hokuto Shobo.

Yomota, Inuhiko. Manga genron (A basic theory of manga) (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo, 1994).

i. Born 1937. Though still alive, he has not published a new manga since 1987. Note that in this paper Japanese names are given with the family name first, personal name second except where quoting works that use the reverse order.

ii. Comparisons are odious, but for what it is worth I personally would rank Tsuge far above the overrated Tezuka as an auteur/artist. I would also rank Shigeru Mizuki, Sanpei Shirato and several others above Tezuka.

iii. All three have been reprinted in numerous Japanese editions. I used a cheap paperback edition that handily covers all Tsuge’s major Garo period works in two small volumes (Tsuge 1994a, 1994b). ‘Chiko’ is in volume 1; ‘Seaside’ and ‘Mr. Ben’ in volume 2.

iv. The exception is an unauthorized and rather stilted translation of ‘Chiko.’ Along with various other unofficial Tsuge translations, it can be found at SAP Comics.

v. The first being ‘Numa,’ (‘The Swamp’), published a month earlier. This also has a poorly translated scanlation at SAP Comics.

vi. This story starts with a girl finding a wounded duck struggling in a swamp and ends with a young man standing by the swamp and shooting a bullet into the sky.

vii. Mitsumame – a mixture of gelatin cubes, boiled beans, and fruit topped with molasses.

viii. Readers may object that “narrative of perspective” or “perspective of the narrator” would make more sense, but “narrator of perspective” is the precise meaning of Takeuchi’s Japanese expression.

ix. Readers of my previous IJOCA paper on ‘The Incident at Nishibeta Village’ will notice a recurring theme here in which a fish escapes from a fisherman only to be killed anyway – by hanging in ‘Nishibeta’ and by impact with the sea here. In both stories, the fish and fisherman are both defeated, with nihilistic implications.

x. A popular Japanese religious movement that branched out from Nichiren Buddhism. A massive social phenomenon, Soka Gakkai today controls a major political party, Komeito.

xi. The Torioi Festival also features at a dramatic juncture in the famous novel Yukiguni (Snow Country) by Nobel literature prize winner Kawabata Yasunari. That novel deals with a doomed love affair between a rural geisha and a wealthy traveller from Tokyo. Tsuge’s story echoes Kawabata’s in various suggestive ways, and if my theory about Ben’s son is correct there may be an oblique reference to Yukio, the consumptive youth who dies in Kawabata’s novel.