In his study of the Batman TV show from last year, Matt Yockey argues that season three’s introduction of Batgirl (Yvonne Craig) carefully maintains patriarchal norms. Batgirl is always subordinate to Batman, Yockey says, and/or to her dad, Commisioner Gordon — or even to Alfred. “The implicit threat of the female crime fighter is contained by Alfred’s knowledge of her dual identities.” Batgirl gets to be somewhat heroic, but ultimately some guy in Gotham is always the boss.

This analysis fails to take into account one small fact. Namely, Season Three (or at least the first few episodes I’ve seen) is not an ordered hierarchy. Instead, it is a huge, staggering, lurching mess. The second episode in particular, with Frank Gorshin returning as the Riddler after a season long absence, teeters on the verge of utter incoherence, before plunging gleefully over the edge.

Seasons 1 and 2 followed a regular two-episode formula arc, from the introduction of the villain to the meeting with the commissioner through the cliffhanger to the escape and on to the defeat of the bad guy. But season three exchanges the two-parters for single episodes, and throws in the addition of Batgirl as an extra bonus crimefighter. The result is a plot that see-saws widely every which way. The Riddler pretends to be the prizefighter Mushi Nebuchudnezzer, drugs various prizefighters, wheels Joan Collins out as a super-villainness who sings a high-pitched note to mind-control other prizefighters, calls Batman a coward to lure him into a fight, uses magnets, tries to mind control Batgirl, fails, and connives with a sports reporter as the narrative veers back and forth between Batgirl running around and Batman and Robin running around, with a brief interlude for Dick Grayson’s aunt Harriet Cooper to explain that she’s been traveling abroad. The winking, knowing humor of the first two seasons dissolves into manic idiocy, summed up by Frank Gorshin bouncing and bobbing around the prize-fighting ring, looking punch-drunk one moment, walking into Batman’s fist the next, gleefully punching the magnetized Caped Crusader from behind in the third.

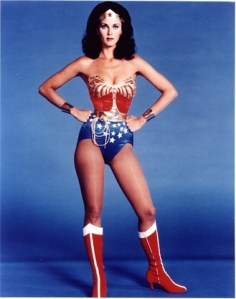

I guess it’s possible that the show’s creators were nervous about the threat of a female crime fighter and were trying to carefully maintain patriarchal order. But that’s not what happens. Instead, the introduction of Batgirl coincides with a show going utterly off the rails. Batman, who in earlier seasons has every answer at his bat-gloves’ finger-tips, now seems to be almost drowning in the whirlwind of plot. He doesn’t know who Batgirl is, and barely seems to know what he’s doing as he thrashes around in the ring with the Riddler until Batgirl demagnetizes him. In the next episode, (featuring Joan Collins again in a skirt so short it’s amazing it got past the censors) Batman, who has been resistant to the blandishments of all other villainnesses, has his Batbrain scrambled, and has to be rescued by Batgirl and Robin.

I wouldn’t say this is some sort of programmatic feminist message. But the first two seasons of Batman always carefully balanced celebrating the superhero as all powerful fuddy-duddy force of order and mocking him for being an all powerful fuddy-duddy force for order. In season three, the female crimefighter arrives, and the fuddy-duddy force for order experiences some sort of apocalyptic bat seizure. System disintegrates; super-villains profligately flock together, Bruce Wayne’s will, heretofore inviolable, is mushed by the exigencies of plot and the power of Joan Collins.

Most of the mix up is no doubt a simple the failure of capital, as cratering popularity and slashed budgets undermined the Wayne fortune and the shows’ shooting budget. But part of it is, too, the addition of that Domino Daredoll. Spending narrative time with the Batgirl-cycle may not topple the patriarchy, but it at least leaves it in massive disarray.