I am a rational and even-tempered man by nature. Nonetheless, I can be driven to anger in certain extreme circumstances, such as the screening of films.

Even now, I can vividly recall my last episode: it was at an early afternoon show of 2009’s Watchmen, adapted from the original Alan Moore/Dave Gibbons comics by David Hayter (a contributing writer to various X-Men– and The Mummy-related projects) & Alex Tse (his sole theatrical film credit), and directed by Zack Snyder, a specialist in bombastic medium-budgeted geek-friendly franchise work, semi-revered at the time for his kinetic opening reel to 2004’s remake of Dawn of the Dead, in which Romero’s buckshot satire ably transitioned into a gory round of Crazy Taxi.

Watchmen ’09 was a horrible piece of shit, the absolute nadir of Snyder’s career, attributable mainly, I think, to dispassionate studio maths: Geek-Friendly Director + Superhero-Experienced Writer = Superhero Movie. The possibility that Snyder’s bodies-in-motion/all-sensation aesthetic might prove incompatible with a comic book series renowned for its slow, precision control likely did not enter into the mind of anyone capable of making a decision on the matter, because superhero movies, fundamentally, are specialty-branded extensions of action movie formulae – which is to say, the ‘superhero’ aspect is a means of allowing advancements in special effects and facilitating expansive franchising opportunities. Deviations in tone are at the indulgence of the individual director — provided they are not working for Disney/Marvel — with little discernible need to consult the source material. A superhero comic is a superhero comic is a superhero comic.

Or, perhaps we might say an fx blockbuster is an fx blockbuster is an fx blockbuster.

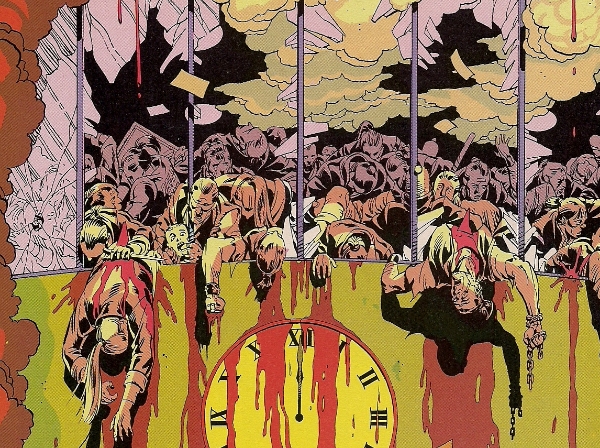

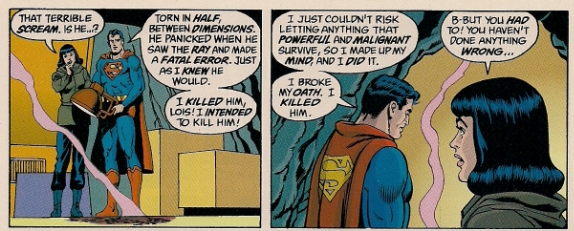

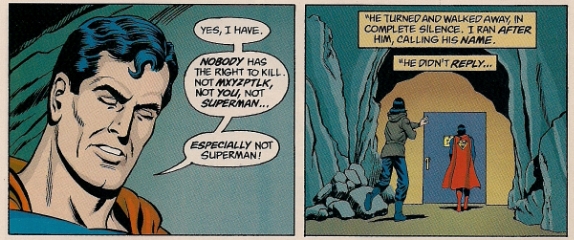

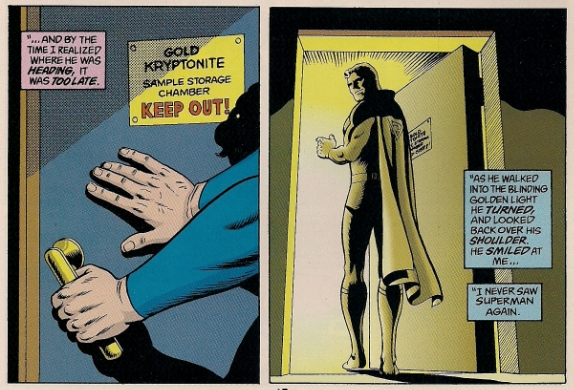

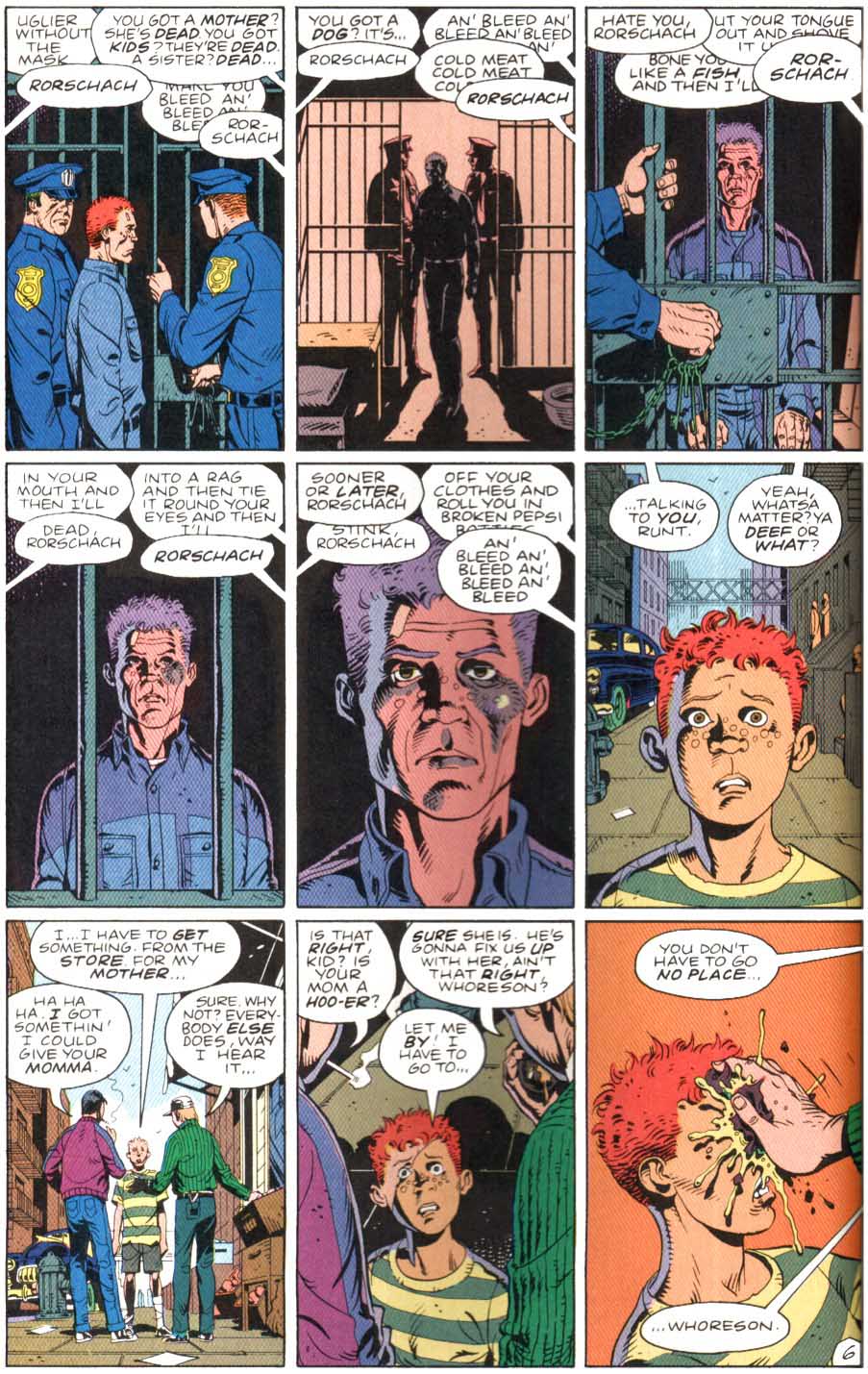

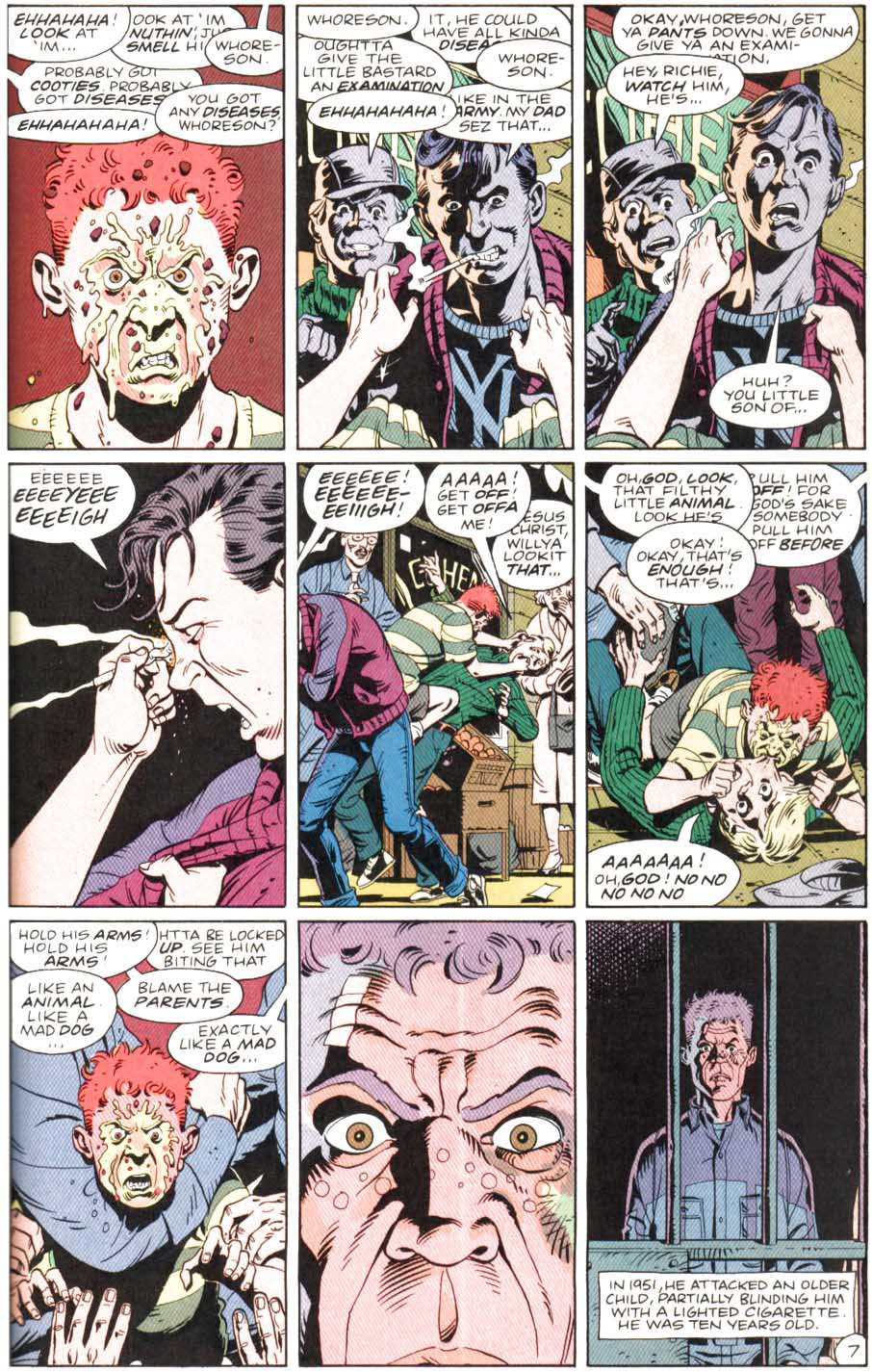

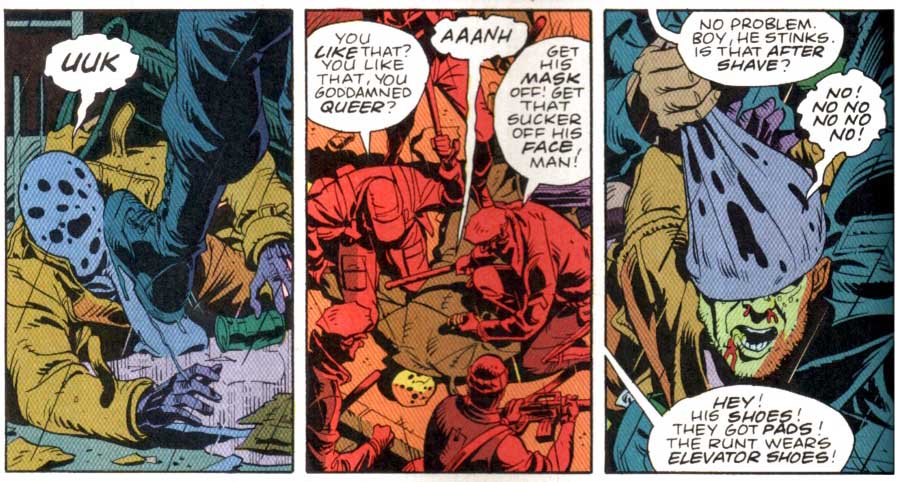

My hands shook in rage at the climax to Watchmen ’09; it was the part where they annihilate the city, and I had no refills left on my popcorn. I couldn’t have cared less about the fucking squid — and even now, close to half a decade later, where the befuddling fandom acceptance of that misbegotten project has faded into a sheepish Oh Well, you are still guaranteed to have any objection to the climax of the film met with ‘get over the fucking squid’ — because all I could see in front of me was sparkling-clean CGI decimation: New York vaporized into a bloodless field of stone rubble. Heresy! Travesty! People say the problem with the film is its hidebound adherence to the comic, but this is only half the problem: it is notionally ‘faithful,’ but lacks many of the specific visceral cues of the original work. The Moore/Gibbons Watchmen was as subdued in its violence as it was in its page layouts, until that awful moment where the blood POURS and the grids EXPLODE into booming splashes, forcing us to feel the transgression to which its superheroes are party, shaking the very foundations of their comic book universe.

That said — because I am vulgar, but not so much an auteurist — I cannot blame Zack Snyder as a purely affirmative actor. He had $130 million studio dollars under his oversight, and having an “R” rating withheld for depicting a holocaust as a holocaust would be tantamount to chucking bushels of cash money into the furnace of an engine careening toward a sheer cliff. Of poverty. The irony, of course, is that ‘important’ topics are frequently given a societal nourishment’s leeway in ratings considerations, but a superhero movie? Forgive me for repeating myself, but again: there is no substantial difference between Watchmen and Green Lantern in the fx movie calculus, they are superhero movies, and it is already a goddamned miracle that one of them snuck away without a PG-13 restriction, which *only* happened because a pair of half-billion-dollar-grossing Frank Miller adaptations could be processed as ultra-stylized Crime and War pictures. Suddenly, the ferocious opposition authors gave to the notion of a comic book ratings system around the time of the Moore/Gibbons original makes a lot of sense.

That’s the kind of shit you have to deal with when you’re Zack Snyder. Half the thirteen-year olds in the United States of America imbibe exquisitely gory martial violence every single day whilst calling each other faggots during marathon gaming sessions, and that’s because dorky, costly video games — unlike movies and comics — initially faced sluggish acceptance as a valid avenue for mass culture, allowing it to bypass much of the heavy breathing over its societal impact until it was already established as a gigantic capitalistic force. As such, if you’re chasing an audience which now equates ‘thrills’ with ‘nonstop violence’ — and if a movie studio gives you $130 million dollars, guess what, you’re chasing it — you need to make things as sensational as possible while also bypassing those niggling concerns over beloved cinema as a pollutant of mental hygiene.

And there’s an old, easy solution to that: make the violence clean. That’s why nobody uses squibs anymore to simulate gunshot wounds – if you use CGI, you can scrub away the nasty effects of shootings when necessary so that they register as murders in a white hat/black hat western. It’s just that there’s more of them. Lots more. An absence of blood in extraordinary quantities! As an accomplished, successful director of films of the type, Snyder has doubtlessly internalized these techniques, and imparted such wisdom to his crew, in the unlikely event they — professionals all — were not already hip.

This is why arguments were made as to whether Watchmen should even have *been* a movie, but I suppose that’s not so much asked about superhero comics anymore.

***

Anyway, now everyone hates Zack Snyder, largely due to the next live-action film he directed: 2011’s Sucker Punch, which he also co-produced and co-wrote. It was the obligatory passion project you get to make after serving xx number of successful years as a good soldier: his Inception, in more ways than one. Tracking the queasy travails of young, exploited girls through numerous cross-pollinating levels of masculine dreamtime fantasy, the film married intense images of geek culture sexualization to furious denunciations of the male gaze in a profoundly bizarre manner. Watching it was like seeing a filmmaker struggling nakedly with his indulgences, and at best fighting them to a draw – idealizing women in a Chaplinesque manner which, by their profound suffering, strips them of agency. Names as diverse as Lucile Hadžihalilovic and Lars von Trier spring to mind in comparison, with all their clashing ideological baggage crammed into the trunk of a speedy genre vehicle.

There was little nuance to the film’s reception, though. Sucker Punch is one of the most widely-loathed films in recent memory, overtly *hated* to the extent that Snyder’s prior films became tainted by association. Duly empowered, dissenters to the sexual violence of 300 and the general cluelessness of Watchmen broadened and intensified the scope of their criticisms to the point where “Zack Snyder” became synonymous with “trash.” I can understand why it happened: Sucker Punch is indeed a broken, fucked attempt at a feminist statement. Yet it worries me that the film’s attempts to be a feminist statement carry no apparent rhetorical value, and, moreover, are commonly misidentified as a brazen, belching effort at the ultimate in deliberate objectification, with little reference to the ‘text’ of the film beyond Just Look At It. I did look at it! I swear! And what I saw was an opportunity for a detailed analysis of what did and didn’t work — a ‘teachable moment,’ to be condescending as hell — falling by the wayside in favor of wholesale denunciation on the basis of received wisdom. I tried, nobody bit.

The message to Snyder, and the people in any position to fund his efforts, must have been very clear: do not try this shit again. Play it safe next time. Go back to what you were doing before.

So we can blame you more when you do.

***

I’m not in any place to defend Snyder’s Man of Steel; I haven’t seen it. From what I’ve been reading, both inside and outside of the nerd conversation bubble, there’s a big debate brewing now over depictions of sanitized violence and the ethics of lethality in popular cinema. I welcome this, although I do find it funny that it was necessary to have a man dressed as the American flag whooshing around disaster areas to prompt such widening concern; so much for the argument that superhero movies are unnecessarily blunt!

Also, I can’t help but wonder why similar concerns didn’t crop up for such critically-acclaimed action bonanzas as director J.J. Abrams’ Star Trek, which opened the same year as Snyder’s Watchmen, and featured as a particularly zippy set piece the destruction of the planet Vulcan and the obliteration of billions of humanoid alien-persons. That’s a Star Wars trick, granted — and look what Abrams is directing next! — but it sat heavily with me as I realized the film’s screenwriters had absolutely no substantive emotional fallout planned: it was merely the signal of pathos necessary to allow some mild identification with fan-favorite corporate holding Mr. Spock. A box was checked, and then onward – to greater adventure!

It is a systemic problem. Perhaps it is only visible now because Superman carries a particularly weird set of viewer expectations, and Snyder is a very easy, zero-cost target for criticism at the moment; no death threats for fucking with him.

As luck would have it, though, there *was* a blockbuster-style fx movie in play this summer that offered a real alternative. A genuine response to all that plague us.

It was derided by critics to a spectacular degree.

I will be blunt. After Earth — an M. Night Shyamalan film, written by one-time video games journalist and occasional comics writer Gary Whitta, with Shyamalan himself (among various uncredited helping hands), from an original story by co-producer/star Will Smith — is not a particularly good movie. This, I admit, is reason enough for critics to reject it, though the conversation surrounding the film has not fit the mold typically set down for a summer flop. There is palpable glee to the denunciations, doubtless owing to some combination of: (1) the film’s relationship to Scientology; (2) the general air of circus ridicule that follows M. Night Shyamalan, who’s mocked in only the way a weird dude who got praised too much too early ever is; and (3) Will Smith’s own efforts at breaking his son Jaden into movie stardom by sheer force of indulgence, an acceptable practice in Bollywood, maybe, but not in these here United States, where everyone succeeds by the sweat of their brow and effort always correlates to reward, save for with those few bad apples who perpetually demand plucking.

Regrettably, After Earth is also the only would-be tentpole this year directed by and starring non-whites, which adds an extra drizzle of WELCOME TO EARF and “Shamalamadingdong” jokes to the comments section mix. Worse, it is arguably a non-Judeo-Christian work (by non-whites) that insists on operating as a serious religious allegory; much attention was paid to a recent Shyamalan interview in which he claimed to have ghostwritten the 1999 Freddie Prinze Jr. vehicle She’s All That, but the real juicy tidbit was the director’s profession of admiration for Terrence Malick’s brazenly churchy The Tree of Life. That’s fitting, given Shyamalan’s disposition as an artist; reared Hindu, he is nonetheless fascinated by the emotive and mystic capabilities of the Catholic and Episcopal faiths that surrounded him growing up in Pennsylvania. Thus, he would make the perfect collaborator for Smith, who is not officially a Scientologist but obviously sympathizes with the gathering in an intense, here’s-my-money fashion.

There are some who deny that After Earth is Scientology-based. Indeed, the Church of Scientology International’s own director of public affairs pooh-poohed such readings, claiming that the film contains themes “common to many of the world’s philosophies.” Which… of course! Why wouldn’t M. Night Shyamalan, good student that he is, suggest (say) Scientology’s focus on clearing the analytical mind of wicked engrams from prior days and prior lives to ascertain the state of the present as parallel to the karma yoga of the Bhagavad Gita, promoting perfection in action through disassociation with Earthly qualms and attachments? Fear is an illusion, after all.

So let’s play a game right now. Let’s set aside, for a moment, our concerns about Scientology, and divine from the resultant Smithian text a solution to the blockbuster problem.

Fundamentally, After Earth rejects the idea of ‘raised stakes’ as a necessary component to the fx extravaganza. What is at risk in the story of the film — seeing Jaden Smith’s anxiety-ridden, anime-like lonely child protagonist, complete with Neon Genesis Evangelion plug suit, stranded on the wild, overgrown, anti-humane landscape of a far future Earth, racing against time to raise a beacon to save himself and his similarly-stranded military hero dad (Will Smith), all the while stalked by an alien beast that tracks its prey by sensing its fear — is nothing more than the lives of two people. There is no galactic threat, no planetary devastation, no mission to eradicate the monster alien race, or reclaim the Earth, or win a war. There *was* a war with the aliens in the past, and it claimed the life of Jaden’s sister, and he is haunted. He does not want to lose his father, or his own life.

In other words, every life is sacred. It is a *terrible* thing when people die. ALWAYS. Candidly, the film could have done better to emphasize this message. There is a considerable amount of time spent near the beginning of the film with the crew taking the Smiths across space, and none of them are particularly memorable; there is little emotional punch to their deaths when the ship inevitably crashes. A cynic might accuse the film of only really valuing the lives of the famous movie star Smiths, so intense is the focus on them. Yet it is nonetheless extremely clear that the deaths of the crew — the absence of lives — has a ready and palpable effect on the mission Jaden is forced to undergo. And we do see some bodies, strung up by the alien monster. PG-13, yes, but not invisible.

Not emotionally sanitized either. Jaden Smith has been lambasted for bad acting, but this is mostly a problem of hesitant and uncertain vocal delivery. In terms of bodily acting, facial expressions, reactions – the kid is pretty good at playing a nervous wreck. He is absolutely terrified for four-fifths of the runtime, hyperventilating in a sickeningly realistic manner, and at one point writhing and grimacing under the sway of toxins, his face swelling into a grotesque CGI mask that ably magnifies his natural expressions of agony until he throws himself onto a syringe of antidote. Warfare, battle, survival: After Earth posits these scenarios as FUCKING SCARY, and, moreover, situations in which one must rely on others to survive. Jaden of course has his dad’s stranded voice to inspire him, but he also encounters a more immediate ally in the form of a large, intelligent bird, who repays his small kindness with a selfless moment of aid.

It is almost a parody of the far more consumptive flying thingy/humanoid relationships in James Cameron’s Avatar, for Whitta & Shyamalan are prepared to extend the capacity for empathy to all smart things.

Ah, but what about the alien? The antagonist Other? Obviously the monster is intended to represent the limitations on human transcendence, but can’t it also be a handy means of demonizing all manner of corporeal foes? Is this not just a softer hymn to battle, to conquest?

(Hang on while I jump off the high horse and crack an M. Night Shyamalan joke like it’s 2002.)

TWIST: I’m not actually opposed to violence in movies! I’m not even opposed to sanitized violence! They pulled that shit all the time in old issues of 2000 AD, and those comics are like my personal Silver Age! Fuck Superman! As originating editor Pat Mills (specially thanked in the collected Watchmen) once wrote of his killing machine hero robot Hammerstein, I am “programmed to enjoy action and destruction.” But just as Alan Moore grew wary of popular films when he saw how the budgets of undemanding entertainments swelled to rival the GDP of small nations, so did the anonymous killings of summer and summery movies begin to wear me down. At least when Django Unchained leers at its dead you can see their faces.

Religious texts are generally not opposed to depictions of battle either, which is one capacity by which they can become instruments of oppression. Yet the climactic struggle of After Earth, perched on the trembling precipice of a mighty volcano — potent symbolism in Scientology, as that is where Xenu detonated nuclear bombs to release the thetans of his prisoners for indoctrination into bad religion — is marked by a distinct ambivalence. Yes, Jaden does clear himself of material concern and slay the beast, and it is the film’s great failing as entertainment that this development in his character seems utterly abrupt, divorced from any satisfying sense of dramatic build or character development.

But then, as he and his father are soaring away, Jaden tells Will that he does not want to be a warrior anymore. He does not want to fight things. He would rather divorce himself from violence. It is allowed, because there is no need for a sequel, a franchise. It’s not how you keep conversation buzzing, to let controversy feed the anticipation for your next move, but if critics are serious about their stated qualms, if they are not themselves tackling an outrage du jour to rustle momentary hits as justification for their declining wages, but interested in addressing underlying questions of motivation and depiction, the steaming husk of this capsule fallen to Earth is worth a closer look.