Last week over at the New Statesman, Sophia McDougall had a long piece about how she’s sick of strong female characters.

Nowadays the princesses all know kung fu, and yet they’re still the same princesses. They’re still love interests, still the one girl in a team of five boys, and they’re all kind of the same. They march on screen, punch someone to show how they don’t take no shit, throw around a couple of one-liners or forcibly kiss someone because getting consent is for wimps, and then with ladylike discretion they back out of the narrative’s way.

McDougall also points out that men don’t have to be strong — they can be addicts like Sherlock Holmes or indecisive like Hamlet or puny like Banner. Being male makes them the center of attention, so they don’t need to constantly prove that they’re tough.

Or, to put it another way, they don’t have to constantly prove that they’re men.

McDougall doesn’t quite get to this point, but one thing that you could say is happening in films like Captain America is a disavowal of femininity. Captain America, as the weak Steve Rogers, needs the super-soldier serum in order to be a man. Peggy Carter, a woman, is in an even more agonized position. Rogers can show weakness and overcome it, but the weakness in Peggy, the femininity, is intrinsic, and has to be constantly disavowed and/or smushed. She has to be hyperbolically competent and violent or dissolve into her own amorphous femininity, like the guys turning into puddles of ichor in The Thing.

Part of what has happened in pop culture, I think, is that the focus of misogyny has shifted, at least in part, off of feminine bodies, and onto femininity. It isn’t women who are held in contempt, but the things traditionally associated with women — weakness, passivity, frivolity. But, inevitably, the things traditionally associated with women are still associated with women — which means that folks with female bodies have to disavow femininity constantly if they’re not to be tainted with it. They’re left, indeed, without much space to do anything else. Men can be weird, or geeky, or odd, or conflicted, or even weak, but women have to just spend all their time shouting at the top of their lungs that they’re not women.

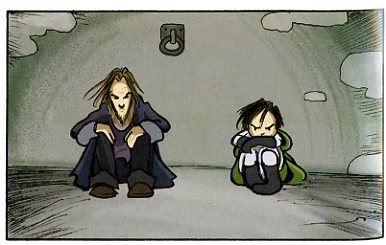

In that context, it’s kind of interesting to look at Ben Hatke’s Zita The Space Girl which I read recently. Zita has at least one of the problems that McDougall highlights as causing the strong female character phenomena. There’s really only one character who’s a girl (though many of the robots and animals are of indeterminate gender.) But that doesn’t seem to translate into the kind of princess-who-knows-kung-fu nonsense that McDougall discusses. Zita doesn’t know kung fu. She is pushy (we first see her engaged in some low-key bullying of her nerdy friend Joshua) but the pushiness is figured (in this initial scene) as a character flaw — a weakness, not a strength. When they find a weird alien remote control, she insists on pushing the button, sending Joshua into the other dimension and generally messing everything up.

Don’t get me wrong; Zita is totally a hero. She’s extremely brave; she goes off into the other dimension to rescue Josh though she doesn’t have any idea what’s there. And she’s compassionate and smart and game (though not exactly feisty.) But a lot of what makes her a hero is not “strength” and “competence” (stereotypical male heroic traits) but more feminine attributes — compassion, empathy, a talent for making friends, and a capacity for self-sacrifice.

So why is Captain America so unwilling to let it’s female lead be female, while Zita the Space Girl seems happy to shuffle male and female characteristics. Why isn’t Zita afraid that its protagonist will be too feminine?

Probably a big part of the reason is that Ben Hatke is just a smarter creator and a better artist than the hive mind that put together Captain America — certainly, I would say that Zita the Space Girl is pretty much categorically better than Captain America as a work of art (not a high bar or anything, but Zita clears it.)

But I also think that part of what’s happenening in Zita, part of why she can be weak as a strength, and strong as a weakness, and not know kung fu, is that she’s a kid. Kids, even female kids, don’t have to prove their men. If they’re not fully competent and self-actualized and don’t know martial arts, that’s not because they’re victims of creeping feminiity; it just means they haven’t grown up yet. If she pouts when she’s angry at you rather than clubbing the guy she’s angry at…well, that’s not because she’s a weak woman, it’s because she’s a nine year old or whatever, and he’s way bigger than her.

What we’ve got, then, I’d argue, is a kind of tomboy-in-reverse. Once upon a time, younger female characters were given a special dispensation to take on masculine attributes; to be adventurous or daring or competent or even violent. Now, in a perfect reversal, the girl’s youth gives her a special dispensation, not to be masculine, but to be weak.