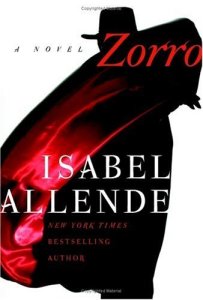

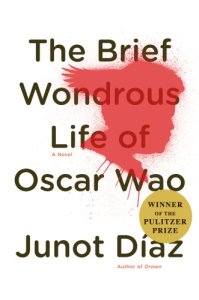

In their works, Ana Kai Tangata and Zorro, Scott Nicolay and Isabel Allende use subterranean features, specifically caves, as a mirror to their male character’s relationship with females. Although Nicolay and Allende have vastly different writing styles and storylines, their main characters are strikingly similar in one major aspect: All of the men in Nicolay and Allende’s works have flawed relationships with females. However, despite external similarities, Nicolay and Allende portray their male characters in different lights. For Nicolay, the relationships his male characters form with women are unacceptable. These relationships isolate the men enough to leave them vulnerable to the “weird.” On the other hand, Allende rewards and romanticizes her male character’s interactions with the feminine. Paralleling caves with the female body in Nicolay and Allende’s stories allows the reader further insight into gender relations in the universe of Ana Kai Tangata and Zorro. In Allende’s universe, the caves are sacred, a place where Diego seeks solace. However, they also clearly belong to Diego and his group of followers. Conversely, the caves in Nicolay’s works are grotesque in nature and clearly the realm of powerful, albeit terrifying, female characters. Ultimately, how Nicolay and Allende write about caves depicts the morally accepted roles of masculine characters within their created universes.

To begin this discussion of cave symbolism in Nicolay and Allende’s works, it is necessary to explore the concept of ecofeminism. As one scholar defines it, “Ecofeminism argues that there are important connections between the domination and oppression of women and domination and exploitation of nature by masculinist methods and attitudes” (Kaur). Ecofeminism has gained credence and popularity in the last few years, as it seeks to understand not only the relationship between the female body and the earth, but also how this relationship either empowers or disempowers women. In literary works, especially, Nature is often linked to the feminine form, while Reason/Logic are linked to the masculine (Gaard 118). Indeed, the figure of the Great Mother Earth is one of the most famous Jungian archetype, standing directly opposite to Logical Man. This dichotomous relationship between Nature and Logic mirrors the binaristic mode so common in patriarchal cultures. It assumes the mind is inherently separate from the body, thus creating a centralized “One” and an ostracized “Other.” The field of ecofeminism connects the “othered” Nature with the “othered” female and attempts to reconcile their place on the outside. Furthermore, ecofeminism is “committed to exposing the ways in which certain groups maintain their superior status through the subordination and domination of women” (Mallory 177). In other words, the ways in which men interact with the Earth are not only symbolically, but also literally, mirrors of how they are expected to treat women within their culture.

In the case of Ana Kai Tangata and Zorro, the most representative natural feature of the female body is the cave. Although extensive analysis has not been conducted on cave symbolism in literature, there is a long anthropological and oral history linking caves to the womb. As Doris Heyden writes in her commentary on cave symbolism, “In all cultures and in almost all epochs the cave has been the symbol of creation, the place of emergence of celestial bodies, of ethnic groups and individuals. It is the great womb of earth and sky, a symbol of life” (Heyden). Furthermore, caves share many of the same physical attributes as the womb: Dark, wet, round, hidden within, etc. They also act as literal entrances and exits from the earth, suggesting both the reception of the penis during sex as well as the expulsion of the child during birth. In analyzing the male characters in Nicolay and Allende’s books through an ecofeminist lens, it is important to realize the potent symbolic and literal relations between the caves and the female body.

Before delving into literary analysis of Ana Kai Tangata and Zorro, one must clarify the types of relationships Nicolay and Allende’s male characters have with females. Allende writes about her main character, “Thanks to his natural charm – which is more than a little – and his awesome good luck, he has been loved by dozens of women, usually without inviting it” (168). However, while Diego de la Vega participates in various sexual escapades, he never develops an emotional attachment to these women. The only exception would be Amalia, the gypsy woman, who acts as both a Mother figure as well as a sexual partner to Diego. However, Allende reminds her reader that Diego’s “emotions were compartmentalized, parallel lines that never crossed” (168). In other words, love and lust never overlap in Diego’s world. While he cares for Amalia as a mother figure, he does not love her in a romantic way, therefore making sex with her possible. Indeed, as Isabel reveals at the end of the novel, “I realized in time that our hero is capable of loving only women who do not love him back” (390). For Diego, the elevated concept of love exists separate from and above the physical female body. The romance he creates in his head is entirely separate from the female’s physical form, allowing him to objectify women while still maintaining the aura of a romantic gentleman.

On the other hand, Nicolay’s characters are not romanticized in any way. In “Phragmites,” Austin Becenti continuously recalls his relationship with Sam, stating, “He more likely would’ve laughed had he foreseen how far south this relationship would go and how fast it would go there” (Nicolay 122). Their rocky relationship haunts him throughout the entirety of the text, culminating in the revelation that Austin is actually Sam’s half-brother. Although Austin’s story is less sexual than many of the others in Ana Kai Tangata, his failed relationship with Sam is still a prevalent trope throughout “Phragmites.” In “Tuckahoe,” Donny Cantu is a much more sexualized character, though he also has a significant association with Alyssa Campion. Their relationship is highly sexualized, as witnessed by their first “date,” in which “Donny looked her up and down without apology now, tits and hips and smooth creamy skin. Hair short and shiny and black as a crow’s back” (288). Their sexual chemistry extends further when Donny recalls, “She’d gotten her rocks off a bunch of times but Donny just couldn’t come … still had all his cookies as Martina used to say although when she said it she said it for herself – and to critique his performance” (292). Not only does this statement suggest the sexual nature of his relationship with Alyssa, it also suggests the existence of past sexual lovers. Presumably, he did not share a sturdy relationship with these other women either. Unlike in Allende’s works, these troubled relationships between Austin and Donny and their female counterparts are representative of their failed masculinity.

Perhaps one of the most important means of discussing masculine power in Ana Kai Tangata and Zorro is the way in which the male characters inhabit the female space of the cave. In “Phragmites,” Dennison pushes his cousin into the cave. Thus, Austin enters the inner space of the cave against his will. Afterwards, he lies incapacitated on the floor of the cave, broken and battered. Nicolay describes the scene aptly, writing:

He couldn’t tell for how long, knew only that he came to aware all at once of a gap and of his battle for breath. A weight compressed his chest and what little wisps of air he could manage rasped in his throat. He tried to scream as panic swept him but squeezed out only a whispered croak (162).

From the time he enters the cave until the moment of his untimely death, Austin is a prisoner of the cave. Even in the face of his own death, he is helpless, unable to escape the advance of the Spider Woman. In this way, the cave strips Austin of his masculine power, both physically and mentally. Not only is his body destroyed – “His torso though was become an arena of blunt agony and his right leg had caught beneath itself and bent with a crack … He was fucked up enough already. He could tell that much” – but he is also left mentally devastated. After his fall into the cave, Austin denies the hopelessness of his situation for quite some time. He continues to go through the steps leading to his rescue in his head, including, “Dennison calling for help, walking back down the mountain if he had to. A chopper. Airlift. ER.Surgery … Whatever it took. Put him back together again” (162). Despite the fact his cousin knowingly and willingly destroyed their only means of transport back down the mountain, in addition to purposely pushing him into the cave, Austin believes he will escape with his life. He only understands the true nature of his situation when he hears Sam’s cell phone ringing somewhere inside the cave. At this point, “A depthless sob racked his torso and he gasped in anguish and agony … He began to cry for real then” (166-167). Although he appeared to have been holding it together prior to this realization, Austin loses control of his mental facilities entirely when he is confronted by the dead body of his ex-lover. Ultimately, both Austin’s physical and mental capacities are broken down, leaving him in the control of the cave. Thus, the cave actively works towards destroying the masculine entity in its physical and mental form.

Similarly to Austin, Donny in “Tuckahoe” enters the cave unwillingly. In this story, Nicolay makes a very blatant comparison between the cave and the vagina, stating, “Donny leveled the 9 at the tall man’s chest just as the ground split beneath his feet and sucked him in quick and smooth as Alyssa’s snatch had swallowed his cock the night before” (Nicolay 327). Before being swallowed by the earth, Donny attempts to confront Storch with his gun, not realizing until too late “bullets won’t do much good on them” (335). Taking the gun as a phallic symbol, Donny’s masculinity fails him at the moment he most needs it. He also goes through a similar process of denial as Austin, thinking through in his head an escape plan:

Donny calculated how he could clear a path with just two rounds left, make his route out, how to get to a main road and a radio. Most of all a radio or a phone. Maybe that neighbor with the chainsaw if he was still around. Then backup. Lots of backup. National fucking Guard backup (327).

Despite his best efforts, however, Donny falls victim to the cave. During his time there, “He hung in the open, no wall behind him, wrists wrapped in some thick cords, ankles also bound” (Nicolay 329). The scratches on his back, given to him by Alyssa during their sexual tryst, appear to be supporting him, or at least keeping him alive. Like Austin, the cave drains Donny of both his physical and mental prowess, though the process takes somewhat longer for Donny. And, while Donny does endure a great deal of physical torment, the focus on his loss of mental abilities is more pronounced than in “Phragmites” After some time hanging in the cave, Donny realizes “what thoughts he managed were muzzy and no longer his own … He drifted in a daze now, no division between waking and dream, nightmare long since his life as much as his dreams” (330). Indeed, even after his physical death, Donny’s mental anguish remains present. At the end of the story he watches a very pregnant Alyssa pick up his own brain. In this scene, Nicolay simultaneously reinforces a resemblance between Alyssa and the womb-like cave and also suggests the control they both have over Donny’s body and brain.

In contrast to the male characters in Nicolay’s work, Allende’s main character moves through the caves much more freely. Diego/Zorro enters/exits the caves whenever he pleases. Indeed, sometimes, such as in the case of the tunnels at the old prison, they seem to appear to him like magic. However, the most telling sign of Diego’s power over the caves occurs shortly after his grandmother introduces him and Bernardo to the sacred caves around their house. Here, “Diego, who was slimmer and more agile, crawled inside and discovered a tunnel that quickly opened up enough for him to stand. The boys returned with candles and picks and shovels, and in the following weeks worked at widening the passageway” (38). Not only does Diego use the caves at his whim, he also takes the liberty of physically altering them when it suits his needs. Allende’s character’s “remodeling” of the cave could be quite harmful to the natural balance of the underground world. Even if the widening did not harm the cave itself, the fact that Diego exerts power over the caves in both a physical and mental way is in stark contrast to Austin in “Phragmites” and Donny in “Tuckahoe.” Additionally, Diego houses all of his Zorro possessions, including his mask and whip, inside the caves. After Zorro’s heist at the prison, he also finds in the cave “a wineskin, bread, cheese, and honey to help him recover from his recent bad treatment,” courtesy of Bernardo (375). Here, the caves literally nurture Diego and provide him with a safe space to store his costume and other Zorro possessions. These tokens are closely tied with Diego’s manhood, suggesting his masculine presence in the caves at all times. Thus, he constantly inhabits, in an active manner, the most intimate part of the female body. In doing so, he also shows subconscious control over the women in his life.

Another key factor in analyzing these characters’ relationships with females is through the feminine characters that inhabit the caves alongside the male main characters. In the example of “Phragmites,” one of the most significant feminine characters is Na’ashjeii Asdzaa. The Spider Woman, who eventually kills Austin at the end of the story, maintains a great deal of agency over the caves. Before Dennison and Austin reach the cave, Dennison stresses, “You understand? It’s her cave” (139). Earlier in the story, he also explains “her home was a scary place and the Twins had to think hard about going down there. So scary it was the great moment of decision on their journey. Bones all over. Stink of death” (138-139). In that same story, the Spider Woman gives the Twins eagle feathers, one of the most powerful and sacred symbols in Navajo tradition. Indeed, she helps the two boys who journey to her cave, suggesting she is not an inherently evil force. However, as Austin sees her, the Spider Woman is presented as “the dreadful immensity emerging from the shadowed depths … filling the passage with its bulk” (167). Due to Austin’s terrified description of the Spider Woman, it can be assumed she did not help Austin at the end of the story. Rather, the Spider Woman is almost goddess-like in her ability to both reward and punish men depending on their moral character.

Indeed, in both “Phragmites” and “Tuckahoe,” major female characters appear to be otherworldly or superior to humans. In Tuckahoe, the most omnipresent female figure is Mother Storch, who is mentioned several times throughout the story before the reader is finally introduced to her in a physical form. The way Donny treats Mother Storch at first is careful, as evidenced when he “entered the chamber with slow and deliberate steps and advanced until his light at last began to shine on the base of the immensity direct in his path” (Nicolay 338). The bulk blocks Donny’s path to the exit, literally taking up an entire room within the underground tunnel system. Donny notes, “It was not as high as the haystack from before but reached all the way to the low vaulted roof where it extended out in one vast and slowly pulsing mass” (339). Not long after Donny’s initial encounter with the mass, he finally realizes its true identity: the old Mother Storch, or Mother Leed as she prefers to be called. The monster/ fertility goddess speaks directly to Donny in this story, stating, “You men are great deceivers you are. You only want to push us full of babes and make us do the work. But you always hurt, hurt, hurt” (Nicolay 341). In this passage, Mother Storch addresses the issue of male dominance directly. At the same time, she acts as a powerful female figure, cutting Donny off from the outside world and eventually aiding in his death.

For Allende, the main female character involved with the caves is Isabel. Unlike many of the other females in both Ana Kai Tangata and even Zorro, Isabel is a strictly nonsexual character. Although Allende reveals she has been sexually active by the end of the novel, throughout the majority of the text Isabel is described as someone no man would desire in a sexual context. Indeed, only one man in the entire story calls her beautiful, and that man ends up marrying her older sister. One of the reasons Isabel is desexualized is because of her “masculine” nature. Isabel is described as a very masculine female, especially after their pilgrimage to escape from Barcelona. Alledende writes:

Isabel, strong and slender, was the one who suffered least from the journey. Her features sharpened, and she acquired a long, sure stride that made her appear boyish. She had never been happier; she was born for freedom. ‘Curses! Why wasn’t I born a man?’ (Allende 257).

Furthermore, when Isabel is within the caves, she is actually portrayed as a male. Originally, Diego believes Bernardo, his milk brother, is the only other Zorro. However, after he escapes from Moncada with the help of Zorro and returns to the caves, he realizes Isabel is also Zorro. Although Diego is grateful for Isabel’s assistance, he originally suggests she cannot be Zorro, because she is a female. Although he changes his mind, it is important to note Isabel is not a feminine Zorro. Instead, she is a biological female donning the costume of the very masculine Zorro. Allende introduces Isabel as Zorro by writing, “There he stood, flesh and blood, lighted by several dozen wax candles and two torches, proud, elegant, unmistakable (383). Thus, Isabel should not be read as a strong, independent woman, but rather a woman who is forced to become a male in mind and form in order to enter into the sacred context of the caves. In this way, despite the presence of a female character, the caves are still entirely under the control of the masculine.

The relationship between the female body and the earth is a long-standing literary tradition, dating back to the Greeks in written history, and well before their time in oral cultures around the world. However, as Donald McAndrew points out, “this romantic and ideal view of nature – ‘Mother Earth,’ ‘Mother Gaia,’ the pure, all giving woman – in much of contemporary ecological theory and comes to the conclusion that behind this romantic posture is a nastier side that desires control and power” (McAndrew 376). Thus, writing about the earth in a romantic manner, as Allende demonstrates in Zorro, may initially appear to be flattering to the female form. However, underlying the outwardly praise runs a deep-seated current of male dominance. In writing about the Earth as only a gentle, nurturing figure, Allende creates a very one-sided feminine world. Furthermore, in her portrayal of Diego as both a womanizer and a romantic, she empowers the concept of masculine domination over the feminine. On the other hand, Nicolay presents his readers with a much more three-dimensional portrait of the feminine earth. The caves in “Phragmites” and “Tuckahoe” empower the feminine through the destruction of the male main characters. By reading Nicolay and Allende’s texts through the lens of ecofeminism, the differences in treatment of the male characters by these two authors become clear. While Nicolay punishes and alienates his male characters for their misogyny, Allende creates a world in which misogynist tendencies are either ignored or blatantly rewarded. Thus, the relationships these men have the earth, specifically caves, illustrates the balance (or imbalance) of masculine and feminine power within the world of Ana Kai Tangata and Zorro.

Works Cited

Allende, Isabel, and Margaret Sayers. Peden. Zorro: A Novel. New York: HarperCollins, 2005. Print.

Gaard, Greta. “Toward a Queer Ecofeminism.” Hypatia 12.1 (1997): 114-37. Web.

Heyden, Doris. “Caves.” Encyclopedia of Religion. Ed. Lindsay Jones. 2nd ed. Vol. 3. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2005. 1468-1473. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 12 Dec. 2014.

Kaur, Gurreet. “An Exegesis of Postcolonial Ecofeminism in Contemporary Literature.” GSTF Journal of Law and Social Sciences (JLSS) 2.1 (2012): 188-95. ProQuest. Web.

Mallory, Chaone. “Locating Ecofeminism in Encounters with Food and Place.” Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 26.1 (2013): 171-89. Web.

McAndrew, Donald A. “Ecofeminism and the Teaching of Literacy.” National Council of Teachers of English 47.3 (1996): 367-82. JSTOR. Web.

Nicolay, Scott. Ana Kai Tangata: Tales of the Outer the Other the Damned and the Doomed. Nampa, ID: Fedogan & Bremer, 2014. Print.

(Brittany Lloyd is a senior English and Anthropology Major at Washington and Lee University. Her interests include Native American literature, 21st century American literature, Queer Theory, Postcolonial Theory and Ecofeminism. She will be graduating in May of 2015 and hopefully interning in publishing before applying for Ph.D Programs in English. She wrote “’As if the earth under our feet were an excrement of some sky:;” An Ecofeminist Reading of Cave Symbolism in Scott Nicolay’s Ana Kai Tangata and Isabel Allende’s Zorro” in Chris Gavaler’s course 21st Century North American Fiction.)