In July 2007 David Enright was at a Borders bookshop in the UK with his wife and two children when he stumbled upon a copy of Tintin in the Congo by Belgian comics artist George Remi (aka Hergé). The couple couldn’t believe their eyes: was this filth at children’s reach? Worst: was it addressed to them? Here’s what he said:

“So you are married to a monkey and have two little yard apes. Good job. Got bananas?” This is one of the letters and emails that my Ghanaian wife and I received, when we asked that the Hergé book Tintin in the Congo be removed from the children’s sections of bookshops back in 2007.

According to The Telegraph (July 12, 2007), after being contacted by Enright a spokesman for the CRE (Commission for Racial Equality), said:

This book contains imagery and words of hideous racial prejudice, where the ‘savage natives’ look like monkeys and talk like imbeciles.

It beggars belief that in this day and age Borders would think it acceptable to sell and display Tintin In The Congo. High street shops, and indeed any shops, ought to think very carefully about whether they ought to be selling and displaying it.

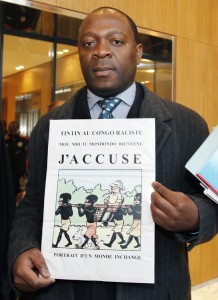

That same month, on July 27, 2007, a Congolese citizen living in Belgium (see above), Bienvenu Mbutu Mondondo, read an Enright related article in a newspaper and decided to act filing suit in a Belgian court against Tintin’s copyright holder, Moulinsart Foundation. After patiently waiting for three years Mondondo, now supported by a French anti-racist organization (CRAN: Conseil représentatif des associations noires – representative council of black associations), extended his suit against Tintin in the Congo‘s publisher, Casterman. The suit was also filed in France.

Mondondo and the CRAN wanted Moulinsart and Casterman to ban the book or, as an alternative, if the first plaint failed, they wanted a warning to be put on the cover of future editions as well as a foreword inside explaining the colonial context in which the book was created (basically they wanted the French-Belgian editions to follow the British Egmont edition). On February 10, 2012, the Brussels Court of First Instance rejected the applicants’ claims. The same thing happened at the Brussels Appellate Court last December 5.

Here are some of the court’s allegations, according to this site:

If we were to follow the appellants, for whom it would suffice to take into account the simple intent of publishing a book, that would require banning today, for instance, the publication of some of the works of Voltaire, whose racism, notably toward Blacks and Jews, was inherent to his thought, as well as whole segments of literature, which cannot be accepted [as] the passage of time must be taken into account. Hergé limited himself to producing a work of fiction with the sole objective of entertaining his readers. He carries out therein candid and gentle humor.

It is above all a testament to the common history of Belgium and the Congo at a given epoch[.]

The Telegraph, again (February 13, 2012) also translated the following court statement:

It is clear that neither the story, nor the fact that it has been put on sale, has a goal to… create an intimidating, hostile, degrading or humiliating environment[.]

Read here the whole document in French.

I’m not a lawyer or, more specifically, I’m not a Belgian lawyer, but come on! “candid and gentle humor”? How can a book that dehumanizes the Congolese people depicting them as childish and lazy and in need of white peoples’ guidance contain “candid and gentle humor”? Are racist jokes “candid and gentle humor”? And how does the entertainment purpose excuse anything? Plus: how can the environment depicted in this blatantly racist book not be “hostile, degrading [and] humiliating”? The known argument that the book reflects its times’ prejudice doesn’t hold water either as I’ve shown, here. Hergé could not invoke an insanity defense. He was responsible for creating racist imagery and racist writing. Others, like Alan Dunn, for instance, at roughly the same time, didn’t do so.

There’s another reason why Hergé couldn’t invoke the insanity defence mentioned above: he’s dead since 1983. Again, I’m no lawyer, but how can a court judge a dead man (guessing his intentions!) is completely beyond me. I know that the “goal” part above is what matters to the court, but in the dubious case that they are psychic isn’t there something called criminal negligence in the Belgian law? What they should be judging is how can today’s copyright owners ignore the racism in one of their books refusing to do anything about it. I can understand why did the Brussels court mention the banning of a book by Voltaire, but Mondondo and the CRAN didn’t want to ban Tintin in the Congo in their secondary plaint, they just wanted to add some heads up and some informative paratext? Here’s what the court had to say about that:

As for the subsidiary inclusion of a warning it is not only an interference with the exercise of the freedom of expression it also hampers the moral right to the integrity of the work which can’t be contested because the defendants don’t own it [Fanny Rodwell owns the moral rights to Hergé’s oeuvre, not Moulinsart and Casterman].

From now on we’re informed that a foreword constitutes a violation of a “work’s integrity.” I can understand the reasoning behind the idea that such a foreword would be a violation of Moulinsart’s and Casterman’s freedom of expression (as well as Fanny Rodwell’s moral rights) though. Said foreword would be forced on them by the court. You’re wrong if you think that I’m on Mondondo’s side on this. I agree with him only when he says that the court suit was a means to force Moulinsart to seat at the conversation table. I understand the strategy, but it was doomed from the beginning: big corporations don’t deal with the little guy. When I repeatedly say on this post that I’m not a lawyer what I really mean is that I don’t want to discuss matters I know little about. (What I do know, however, is that they are lousy comics critics at the Brussels court.) What’s unfortunate is that the publishers themselves don’t comply with Mondondo’s wish for a foreword of their own free will as they should. It shows that Continental Europe is still way behind America and the UK when these matters surface in the public sphere.

Another quote in the court’s decision (written by De Theux de Meylandt, according to this site), states:

We see in particular that Tintin in the Congo does not put Tintin in a situation where there is competition or confrontation between the young reporter and any black or group of blacks, but puts Tintin against a group of gangsters… who are white[.]

I’ll let a Portuguese anthropologist living in Maputo, Mozambique, José Flávio Teixeira, answer to the above for me (in a review of Deogratias, a book about the Rwandan Genocide by Belgian comics artist Jean-Phillipe Stassen):

Beyond a self-centered gaze (ethnocentric: what interests him, above all, is how “his people” behave themselves elsewhere and how they get astray from the recommended “good behavior”) what the book states (distractedly) are two fundamental points: the perennial (the need for?) European leadership; the inferior malevolent capability of the Rwandan people (the African people). Thus crystallizing the racism, affirming white superiority: “people” (race, because, in the end, the book is about race) who are more in the lead, who are more corrupt, meaner. More human, right?

Going back to the UK, Ann Widdecombe, a Conservative politician, criticized the CRE (see above) for their support of Enright’s views (she said that their claim was ludicrous):

It brings the CRE into disrepute – there are many more serious things for them to worry about.

I don’t know if this is an apocryphal story or not (it probably is), but this reminds me of that officer of justice, after Belgium’s liberation, who refused to accuse Hergé of collaboration with the Nazis under the excuse that he didn’t want to cover himself in ridicule. It’s a well known fact: comics are less powerful, less corrupt, less mean. Less of an art form, right?

Just a short note on the recourse to José Flávio Teixeira’s evaluation of Jean-Philippe Stassen’s Déogratias. Though he is entitled to that interpretation of the text, Stassen would disagree wholeheartedly. In interviews (http://gciment.free.fr/bdentretienstassen.htm) and in his work since Déogratias, it is blatantly clear that condemns colonial logic and, more importantly, its continued influence both in Europe and throughout the former French and Belgian colonies. One need only read the dedication on the very first page of Pawa: Chroniques des monts de la lune – one of Stassen’s other texts about Rwanda (Merci beaucoup à tous ceux que j’aime bien au Rwandan et au Burundi. Merci à Godelieve et à Joe Sacco. Je tiens à ne pas remercier les services consulaires de l’Ambassade de Belgique à Paris qui ont fait tout ce qui était en leur pouvoir (et même davantage) pour m’empêcher de voyager.) – to know that he is not only against such racist views, but that he is also committed to challenging all manner of discourses (including visual discourses) that perpetuate colonialist ideology.

Interestingly enough, Stassen’s illustrated version of “We Killed Mangy Dog” by Mozambican author Luís Bernardo Honwana is a more broad critique of all European colonialism in Africa beyond the Belgian (or even Francophone) context(s).

On a side note, Alain Mabanckou’s take on the continued controversy surrounding Tintin au Congo – http://blackbazar.blogspot.com/2010/05/tintin-au-congo-le-proces-continue.html – raises important points and speaks to the larger context and implications of such a controversy. In particular, when asked whether or not Tintin au Congo should be censored or altered, Mabanckou replies:

Non, je ne suis pas partisan d’une interdiction de cette bande dessinée. Elle doit rester une trace de l’esprit belge de ces années trente. Elle est une des preuves historiques d’une certaine pensée occidentale – mais pas de toute la pensée occidentale ! La polémique qui entoure cette œuvre risque de friser la cocasserie à force de ne lire les choses que sous un angle « africaniste », voire «intégriste». Ce n’est pas à partir de «Tintin au Congo» que la pensée du Blanc sur le Nègre s’est formée. Lorsque Tintin est «arrivé au Congo», l’idéologie raciste et coloniale sur le Noir était déjà bien établie.

Il faut remonter à la source, déconstruire cette pensée et poser la vraie question: comment enseigner la colonisation aux enfants ? Oui, la colonisation est un sujet mal abordé en France – c’est presque un sujet «explosif». Et jusqu’alors il se trouve que beaucoup croient encore au rôle pleinement positif de l’Europe en Afrique. La colonisation est un asservissement, point final. Il est ridicule de songer à rajouter un texte pédagogique dans l’album « Tintin au Congo ». Pourquoi ne pas, alors, le faire aussi dans L’Esprit des lois de Montesquieu, où il est dit que les gens du sud sont faibles comme des vieillards et que les gens du nord sont forts comme des jeunes hommes ? A ce train-là il va falloir relire tous les livres du monde et rajouter des pages pédagogiques ici et là !

Une fois de plus, il suffit d’enseigner avec objectivité la colonisation en France, dès le bas-âge, pour que les enfants forgent leur intime conviction et regardent l’Autre à sa juste valeur. Lorsqu’on est enfant, on pense toujours que les héros d’une œuvre sont réels. En apprenant à ces mêmes enfants la pensée coloniale, ils seraient enfin capables de séparer le bon grain de l’ivraie.

Just some food for thought.

I don’t like labels on movies, videogames, or music. The same goes here. Did you need a label to tell you that this book is “blatantly racist”? What’s the point other than to dumb down the world with simplistic slogans?

I can see why a bookstore owner would put a kids book in another section if it contains racist content that kids might not possess enough knowledge to process. Bring it to the shopowner’s attention, make your case. If he or she doesn’t agree and refuses, shop elsewhere if it’s troubling enough for you.

There are problems with movie labels…but as a parent, I have to say they are kind of useful.

Certainly taking your money elsewhere is one option. But is that really the only recourse allowable in a democracy?

I don’t think going to the courts is a good idea, though, as this incident sort of shows. Picketing and public denunciations or other exercises of free speech seem reasonable, though.

M. Bumatay: I don’t doubt that Jean-Phillipe Stassen is not a racist, but these things can function at a subconscious level. Maybe there’s even an unsuspected link between Tintin in the Congo (plus: tons of other mass culture) and Deogratias created in Stassen’s subconscious mind, who knows?

Anyway, I really don’t care much for the legal discussion, really… What matters to me are the court’s inconsistencies and the court’s incredibly bad comics criticism. I don’t want to second guess their motives, but it seems to me that it is legitimate to question their competence to judge a national treasure like Hergé. We’re dealing here with two biases (or so it seems to me): 1) comics are so under the radar and is such a minor art form that it is ridiculous (“ludicrous”) to pay them this much attention; 2) how could this sacred cow not do right?

By the way, it’s also interesting to see that the first bias happened in the UK and the second one happened in Belgium.

I agree with you that it’s interesting that it happened in the UK first and Belgium / France (because of CRAN’s involvement) second, though not surprising due in large part to the differences in the colonial missions of the UK, France, and Belgium respectively and the resulting sociopolitical and cultural issues of today. France’s memory wars speak to such issues.

And as to a possible connection between Stassen and Tintin au Congo – I think it is explicit and purposeful at both the level of form and content. In my opinion, Stassen’s art is a politically-driven deformation of the ligne claire style epitomized by Hergé and, if we compare the various renditions of the scenes in the various editions of Hergé’s Tintin in the Congo and the school scene in Déogratias, then we see Stassen alluding to Tintin au Congo and essentially equating teaching the colonial civilizing mission in Tintin’s classroom and teaching the division of the Rwandan people into the Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa enforced through the use of identity cards by the Belgian colonial officials and politicized by certain groups after Rwandan independence.

And I do not think that comics are so under the radar specifically in Belgium and France given that bandes dessinées are such a large industry and make up a large portion of print sales in both countries and that is precisely one of the main reasons why many people (aligned with and who benefit from the dominant culture) become agitated when Tintin and Hergé (money-making ultra-superstars) come under fire.

There’s slight misunderstanding, here. I meant that the first bias (it’s ludicrous to pay comics this kind of attention) happened in the UK and the second one (the sacred cow had to do right) happened in Belgium. If the economy got in the middle of the court’s decision, as you say, it stops being a bias to start being a corrupt decision.

I read Deogratias a couple of years ago to write a review, but I don’t own a copy and I don’t remember much.

Do you know what the “downstairs” witticism is? Probably not… It’s what happens when someone has left the house, is already going downstairs and remembers a smart retort. Too late, of course…

Well, something similar happened to me here (minus the smart part) hence the delay in my answer to Charles.

Is Charles right in what he says about labels? Maybe, I certainly can see his point, but if in the publisher’s shoes I would want to disassociate myself from this king of imagery and words. If you say nothing you’re spreading the damn thing. You’re agreeing with it. The problem, and this is my main point, is that both the court and the publisher see nothing wrong in the book. This, to me, is simply appalling.

(1) At this date I think it’s irresponsible to publish TINTIN IN THE CONGO in kid-friendly formats without a warning or contextual introduction of sorts. (I specify “kid-friendly formats” because I don’t really have a problem with the expensive, black-and-white facsimile ARCHIVES format version, either the French one or the now-out-of-print Last Gasp English language version.)

(2) That said, I’m very, very, uncomfortable with the idea of legally enforcing the addition of this material under threat of a ban (and I have the American free-speech-libertarian’s extreme discomfort at European and Canadian “hate-speech” bans).

(3) That said, I can well see why someone who was sensitive to the material becoming so frustrated with the adamant refusal of those who control it to concede to this very reasonable request that they take legal action.

(4) And it’s somewhat unfair to accuse Mondondo of wanting to flat-out ban the book when it seems pretty explicit that he’s looking for the contextual warning and the ban is more of an if-they-can’t-agree-to-that threat that is part of the lawsuit.

(5) TINTIN THE CONGO is clearly not harmless, and I suspect those who minimize its toxicity, whether journalists or judges, do so to justify their own squeamishness on point 2.

(6) My guess is that if Hergé was still alive he’d either ask that the book be withdrawn (as it was at certain times) or insist on that kind of contextual material himself.

(7) It’s nice that later in life he was publicly and vocally mortified at the content of TINTIN IN THE CONGO himself, although maybe a little creepy that he seemed more genuinely distressed at Tintin’s bloodthirsty hunting rampage.

(8) I love TINTIN IN THE CONGO.

(9) I recognize TINTIN IN THE CONGO is evil.

(10) But I think in creating it Hergé was at worst misguided and naïve.

Domingos, that makes sense. And so does Kim’s list of points.

It’s a good sum up. Thanks, Kim!…

Noah? There’s only one post (this one) tagged under Tintin in the Congo. Couyld you fix that?

It occurs to me belatedly that perhaps the Hergé estate’s resistance to including that kind of a disclaimer is legalistic. In the same sense that your lawyer will tell you it’s a bad idea if you’re in a traffic accident to say “I’m sorry” to the other driver because it can be taken as an admission of guilt should things get ugly, conceding the racist nature of TINTIN IN THE CONGO in print might, in the context of European hate-speech laws, make the publisher more vulnerable to legal action rather than less. (“They ADMIT it’s racist!”) Making it a classic unintended-consequences legal situation. But maybe there’s someone familiar with European jurisprudence out there who could weigh in.

Sorry Alex; it should be fixed now.

“Do you know what the “downstairs” witticism is? ”

Wit of the Staircase / ‘eprit d’escalier

Kim: see here for a lawyer’s view. He also entertains the strange notion of a foreword in a banned book, but anyway…

—————————-

Domingos Isabelinho says:

I don’t know if this is an apocryphal story or not (it probably is), but this reminds me of that officer of justice, after Belgium’s liberation, who refused to accuse Hergé of collaboration with the Nazis under the excuse that he didn’t want to cover himself in ridicule. It’s a well known fact: comics are less powerful, less corrupt, less mean. Less of an art form, right?

—————————-

Ah, using a dubious line of reasoning to thump on that ol’ “comics are inferior” drum again.

Because some targets — cartoonists, comedians, tabloid newspapers — are better able to retaliate by making their attackers look ridiculous (thus making would-be attackers loath to do so), has no reflection upon the aesthetic qualities of the target’s work.

—————————-

Even before its official unveiling, the Last Judgment became the target of violent criticisms of a moral character. Biagio da Cesena, the Vatican’s master of Ceremonies, said that “it was mostly disgraceful that in so sacred a place there should have been depicted all those nude figures, exposing themselves so shamefully”, and that it was “no work for a papal chapel but rather for the public baths and taverns.” Michelangelo’s revenge was to paint Biagio in hell, in the figure of Minos, with a great serpent curled around his legs, among a heap of devils.

—————————

http://www.robinurton.com/history/Renaissance/michelangelo.htm ; close-up of the “critic as a devil” at http://100swallows.wordpress.com/2007/10/05/michelangelos-portrait-of-a-devil/ . (With ass’s ears; and is that serpent biting his whatsis?)

Re Hergé as a “collaborator,” info at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herg%C3%A9 , http://www.tintinologist.org/articles/defence.html .

—————————–

Kim Thompson says:

It occurs to me belatedly that perhaps the Hergé estate’s resistance to including that kind of a disclaimer is legalistic. In the same sense that your lawyer will tell you it’s a bad idea if you’re in a traffic accident to say “I’m sorry” to the other driver because it can be taken as an admission of guilt…

——————————

I’ve got a copy of the Fantagraphics-published “Cosmic Retribution” book of the brilliant Joe Coleman’s work ( http://www.amazon.com/Cosmic-Retribution-The-Infernal-Coleman/dp/0922915067 ), bearing an easily-removable sticker in the front, “Warning! Contents May Offend!” (Which I never took off; it tickled my fancy.)

Would that approach not do well for “Tintin in the Congo”? A sticker is removable, thus not “violating the integrity” of the book. It can be easily affixed to already-printed books, in the appropriate language, thus inexpensively “retrofitting” them for the more sensitive.

And finally, the wording contains no “admission of guilt”; merely notes that some may react in an untoward fashion to the contents.

(Speaking of a “classic unintended-consequences legal situation,” one account tells how Marvel’s reluctance to give Jack Kirby back his original art was partly motivated by concern that he would then proceed to demand at least part-ownership of the characters as well. [Not defending Marvel here, which should have treated Kirby with the utmost respect and remuneration; just pointing out that something more than petty assholishness might have motivated them.])

Mike: I’m aware that to quote is to decontextualize, but there’s decontextualizing and then, there’s decontextualizing. Your quote above is meaningless without the rhyme with José Flávio Teixeira’s quote. Also: that putative officer of justice didn’t want to cover himself in ridicule not because he was afraid of satire (Hergé wasn’t much of a satirist). He was afraid of ridicule because, in is view (not mine), comics aren’t serious enough to deserve any punishment.

I agree that Mike Hunter’s “fear of satire” argument is nonsensical (sorry, Mike) but I don’t think yours is exactly right either. Domingos. Hergé’s continuing to draw TINTIN for LE SOIR was so far on the venial side of the “collaborationist” spectrum that this, combined with his enormous popularity, made it arguably unwise to drag him into those purges. At the very least in fairness you should say that “he was afraid of ridicule because HE THOUGHT THAT IN THE VIEW OF THE GENERAL PUBLIC, comics aren’t serious enough to deserve any punishment.” Fear of ridicule has to do with his perception of popular opinion on the subject, not his own view.

That makes perfect sense to me, Kim. It’s a nuance that I welcome, but I don’t even know if the story really happened, let alone who this person was and what he (I guess he was a he) thought about comics.

Pingback: Comics A.M. | Tokyo’s Comiket to lose $117,900 due to threat letter | Robot 6 @ Comic Book Resources – Covering Comic Book News and Entertainment

I’m a little late to the discussion here, and thus don’t have much to add that hasn’t already been written. I largely agree with Charles and Kim and Devriendt (the author of that write-up Domingos linked to), with the addition that I’m unsure how harmful something as naïve as Tintin in the Congo can be today. I think there’s a real argument to be made that the book, read today, actually exposes the horrendous racism of its age in very illuminating ways, rather than perpetuating it. The changed context makes it satirical in a way it was never intended to be. (For Danish readers or anyone willing to brave a Google translation, I’ve written a bit more on the issue here).

Not that that makes the book any less racist, of course. And while I think Devriendt is right that pursuing the case in court was counterproductive for general discussion on the book, their lawsuit should be seen in the context of the general lack of official Belgian reckoning with its horrendous colonialist past — something that makes Mondondo’s actions more understandable. (Joël Kotek from the University of Brussels elaborates a bit here).

One more thing: I think Domingos has made this somewhat clearer in comments, but I think it’s important to note that Mondondo and Cran *did* in fact seek to have the book banned from the trade.

The question of harm is such a tricky thing, isn’t it? It’s really hard to know how influential a work is, or how that influence affects people or doesn’t. I know I used Tintin books (not Tintin in the Congo, but other ones) to talk to my son about racism (this was when he was 5 or so I think?)

When there’s something like Tintin and the Congo…it seems like the issue is less “will it harm people?” and more thinking about what sort of society you want to be, or who is included in your vision of what your society is. It seems like it’s important to have a note, or (better) a forward, not so much to prevent damage (which is hard to quantify or prove), but more as a way of saying, “as a society, racism has been a problem for us in the past; this book is one symptom of that, and we’re trying to do better — and one way you can see we’re trying to do better is that we’re acknowledging that this particular book was in a number of ways really fucked up.”

The point is…it seems like the issue is less about protecting the children, and more about etiquette. Etiquette can often get a bad rap, especially from aesthetes who tend to see it as conventional weakness vs. the true power of art, or some such. But… racism is in many ways actually a system of etiquette and social norms (Huck Finn gets at this well, I think), which means that anti-racism is also built around etiquette. It’s maybe a small courtesy to be willing to acknowledge the problems with Tintin in the Congo — but small courtesies can be important.

Matthias: did you read the real document written by the court of appeal? You may do so here. The plaintiffs wanted to ban the existing editions, not the book. If they talk about putting a warning on the cover and a foreward in the album it’s obvious that they didn’t want to ban the book for ever and ever.

Yes, but that is from the appeal, not the original suit brought before the Brussels court of first instance in 2007. I haven’t read the court documents from back then, so I don’t know, but the way the story was reported conforms to point III.2 in the formulation in the court decision document you linked to, which demands an immediate cessation of all commercial exploitation of the book on the part of the publisher and rights owners. This 2007 interview with Mondondo further confirms that his first, if not exclusive, intention was to have the book banned. I could definitely be wrong, but it seems possible that the language demanding insertion of a warning, if an outright ban isn’t granted, came with the appeal.

Noah, I don’t disagree, but I believe that in the present context the book itself is a good Exhibit A if one wants to talk about how horrible early- to mid-century colonialist thinking in Belgium and elsewhere was. Banning it, on the other hand, it would remove (or begin to remove) from public view important historical evidence. And as I wrote, it’s almost as if it’s become satirical of its own ideological position with time. As Mondondo also notes, the book is widely read in the Congo, and surely not taken at Hergé’s face value, which again suggests an interesting contextual shift.

Yeah…I certainly agree that banning it is a terrible idea.

I’m not a lawyer, but it seems strange to me if an appeal, by its very nature, brings new data to the process. Here, in 2010, the foreward is already mentioned. You’re right though. My mistake happened because I didn’t stop enough to consider the word “subsidiaire” (secondary). Here is an explanation that says, more or less: “it’s a plaint that will be judged only if the judge rules against the plaintiffs in the first place.”

Now I need to go back to the drawing board, sigh!…

In fairness, in the 2007 interview Matthias cites, the following exchange occurs:

“Is banning the correct response?”

“Since there is no other solution, [the book] must be eliminated.”

The first half of his response could be read as “Since the publishers refuse to add any kind of contextual commentary…” And you can’t, so far as I know, legally force the publisher to add this — so if the publisher refuses to do so, your only legal recourse is to seek a ban. Moreover, what they were seeking to ban was a specific object, that edition of the book sans contextual acknowledgment. In theory if the courts had ruled for them and the book had been banned Casterman could have re-released the book with this addition and been fine.

You may be right, Kim, but at this point I give up guessing what Mondondo really wanted. To be sure I need to read the plaintiff’s allegation. Unfortunately I couldn’t find it on the www.

The lawyer Ahmed L’Hedim says here: “This comic should be contextualized, relativized, at least, because it conveys negative images. […] We are aware that freedom of speech must be respected, but there are also limits to the freedom of speech.” It’s that “at least” (“au moins”) that worries me. He talks about limits, but he doesn’t explain what he thinks should happen if those limits are reached.

I think the “at least” is just lawyerspeak so as not to close off options. Really, the impression I’m getting is that the plaintiffs and lawyers were aiming for and would have been happy with the contextualizing material, and any harsher demands reflect a combination of needing to put those options on the table as a legal principle (and underlying threat), and cumulative frustration with the obstinacy of the publishers and the Hergé estate.

This is an interesting discussion, particularly of the banning vs contextualization issue. I just want to comment on one passage in Domingos’ original post, which I find problematic:

“What’s unfortunate is that the publishers themselves don’t comply with Mondondo’s wish for a foreword of their own free will as they should. It shows that Continental Europe is still way behind America and the UK when these matters surface in the public sphere.”

That is a pretty broad generalization to draw, of quite a few different countries, based off the decision of one (admittedly large) Franco-Belgian publishing house, no? I don’t mean to come off as an European who got my feelings hurt, but I think the above might be a dangerous conclusion to draw from this sorry affair.

I admit that it’s a huge generalization, but I do it not only because of this particular case. It’s not that I have any scientific hard data or anything, but from European comics scholars to the Belgian court (add also some South American insensitivity to Memin Pinguín for good measure) I’m sure that other countries have a lot to catch up with the U.S. in these matters.

I think all other Western countries are far more profligate in terms of passing hate-talk legislation that could in theory be used to attack this kind of material (as it was here), but American publishers on an individual basis tend to be more sensitive in terms of including advisories and contextualizing material to distance themselves from problematic racial stereotypes, etc.

You could argue socialist vs. individualist if you so chose.

You could also argue that Americans think their public is too dumb to figure it out for themselves, while Europeans give their readers more credit.

Charles put it in those terms too, but I wouldn’t. People who are “blind” to these issues, namely saying things like “what’s the big deal, it’s just a caricature of a black person” (I heard this in reference to Will Eisner’s Ebony) aren’t dumb necessarily. I remember talking to someone from Peru (methinks) who criticized Americans for their condemnation of Memin Pinguín. This because, he argued, Memin Pinguín is a beloved character in South America. Yes, but, I argued, look at the way all the other characters are drawn. Memin Pinguín, like Chop-Chop in Blackhawk comics is what Jones calls the alien character. What I think happens is that it’s more difficult to identify a racist caricature if the culture of a particular geographical area is not awaken to the problem.

I no longer write for The Hooded Utilitarian (it was a great run: thanks Noah!). After being repeatedly bullied (not Noah’s fault, mind you!) I don’t plan any further comments either. I’m making a last exception because a true gentleman passed away. I mean Mr. Kim Thompson, whose intelligent comments (as always) you can read above. You will be missed, Kim!

I was wondering if Kim Thompson’s passing would be noted here with a full post.

For better or worse, HU seems to have inherited some of the more interesting folks from the old Journal message board, but as was the case back then, it’s a mixed bag at best.

I admired Kim very much and enjoyed talking to him a great deal, but…I don’t know that I knew him or his legacy well enough to do a post myself, unfortunately. If somebody more knowledgeable wanted to do one, though, that’d be great.

Domingos will be missed.

Kim acting like an asshole was my final straw with TCJ’s messboard, funnily enough. He had a “with me or against me” kind of disposition (at least online), but that probably got translated as passion when it came to publishing comics. I suspect we’ll have fewer translations of good comics now that he’s gone, which speaks to his importance to the medium.

I really enjoyed arguing with Kim. He was definitely aggressive, but always civil, and hugely knowledgeable, obviously, so I felt I always learned things.

Domingos leaving sucks. I keep hoping he’ll change his mind….