Hanabusa Itcho, Blind Monks Examining an Elephant. Itcho, by the way, not Hokusai, contrarily to popular myth, coined the word “manga.”

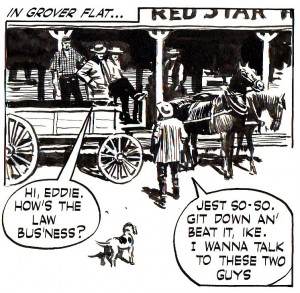

Speaking of stories… you know the parable: the blind men feel different parts of an elephant’s body and, afterwards, they disagree on what an elephant looks like. Such is the nature of truth; knowing only part of it we can’t grasp… speaking of pictures, the whole picture. In another version the men and the elephant are in a dark room, so, as the great Mevlana Rumi put it in this version: “If each had a candle and they went in together/ The differences would disappear[.]” If you didn’t get it already, and there are absolutely no reasons for you to know where I’m heading, I’m referring to the Eddie Campbell vs. Suat Tong or the “picturaries” (as I called them) vs. “literaries” controversy. I guess that the differences of opinion can be extended in an “us vs. them” kind of way to The Hooded Utilitarian (the non-essentialists) vs. The Comics Journal (the former Comics Comics – a great name to describe their philosophy echoing Eugeni Dors’ “painting-painting”). As I see it there are really two disputes, not just one: the aforementioned “various ways to look at an elephant” (Eddie vs. Suat) and the essentialist debate (THU vs. TCJ). I’ll try to address the two.

I’m worlds apart from Rumi’s greatness and I don’t believe that the differences will be solved by my saintly intervention, but, in a true meta-critical stance, I’ll try to do my best. I’ll state from the start that, obviously, I’m an interested part in this debate. Coming from a “picturaries” background, I graduated in Studio Art, I pass as one of the literaries. I don’t see myself as one, though. To explain why let me examine the core (as I see it, of course) of the text that started the whole thing: Eddie Campbell’s “The Literaries” at TCJ’s website:

What appears at first to be taking a more stringent view is in fact applying irrelevant criteria. It dismantles the idea of a comic and leaves the parts hopelessly undone.

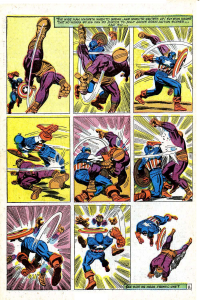

See that elephant over there? Besides, this is where the two debates converge: essentialist Eddie views literary criteria applied to comics as misguided because the true applicable criteria must be about pictures. And yet, what does Eddie consider to be literary specifically? The story or, the plot. The only problem is that in comics the drawings are the story too. To prove it I don’t need to go any further than Lee and Kirby’s (et al.) case in point below, given to us as an example of non-literary excellency in the aforementioned “The Literaries” blog post:

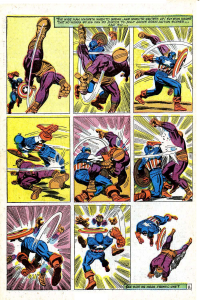

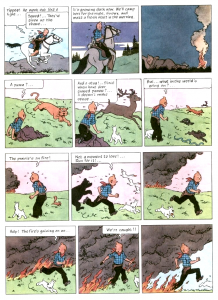

Stan Lee (w), Jack Kirby (p), Frank Giacoia (i), Sam Rosen (l), anon. (c), “The Blitzkrieg of Batroc!,” Tales of Suspense #85, January 1967 (page # 8).

Curiously enough in the above example it’s the words that are self-referential and non-diegetic while the images tell the whole story: two characters beat the crap out of each other. If story equals literature who’s a literary now? Eddie Campbell himself inadvertently acknowledges this when he says:

Now, I am cognizant of the fact that the multitude of kids reading that Captain America were just thinking about what Cap and Batroc were doing to each other.

Exactly so because they were reading a story (the use of the word “reading” is, if you ask me, a co-option by the literary field because those putative kids were interpreting images). Why did this co-option of everything narrative by literature occur? Eddie Campbell didn’t invent it. It’s one of the dogmas of Modernist art of the Greenbergian kind. But Clement Greenberg didn’t invent it either. Here’s what Paul Cézanne said according to Joachim Gasquet, writing in 1912/13 (not exactly a reliable source, but still…):

I don’t like literary painting. […] [T]o want to force the expression of nature, to twist the trees, to make the stones grimace like Gustave Doré, or even to refine like da Vinci, that’s all still literature.

And yet Eddie Campbell doesn’t go that far. What he likes in the above page is clearly the expression (here’s what he says about a performance by Billie Holiday; we can’t compare comics with literature, but, apparently, it is OK to compare comics with literature if in a song; Eddie isn’t much of an essentialist, after all, even if he used the very word “essence” below):

I’m not talking here about technique, a set of applications that can be learned, or about an aesthetic aspect of the work that can be separated from the work’s primary purpose. The performer’s story is the essence of jazz music. The question should not be whether the ostensible “story,” the plot and all its detail, is worth our time; stories tend to all go one way or another. The question should be whether the person or persons performing the story, whether in pictures or speech or dance or song, or all of the above, have made it their own and have made it worthy.

So, Eddie Campbell wants us to pay attention to the artist’s expression (Cézanne/Gasquet would call him a literary I’m afraid). That’s one blind man feeling the elephant and I don’t deny his importance and value. But what about the other blind men? Don’t they feel equally important parts of the beast? Why this rage against the story?

I can’t talk for others, but what I value in a comic isn’t the story per se. What I really value is the meaning. This may be clichéd, but so be it: I believe that great artists reach some kind of truth. (They may be as blind as Itcho’s monks, but they’re very good feeling the little part of reality that interests them.) Doing so I considered already that the technical skills of the artists and writers, their ability to convey feelings (their expression or lack thereof because an artist may choose to convey ideas mainly) were capably handled. This isn’t an either or kind of situation. That’s why the claim that we literaries value Fun Home over Cliff Sterrett doesn’t make any sense (it’s an obvious straw man). Besides, meaning can be found in every mark that the artists and writers create on the page. I don’t see why meaning has to be associated with story and why story has to be associated with literature. By claiming meaning for my main criterion am I calling it the whole elephant? Maybe I am, but I’m as biased as the next guy. Why choose this elephant instead of that one is my next question?

That leads us to the essentialist problem (counseled reading: Leonardo da Vinci’s Paragone): why can I compare a comic with another art artifact? Because meaning is something that we can find in every work of art. Exalting the comicness of comics to us non-essentialists doesn’t make much sense: yes, a comic is not a piece of music, but can’t we find cadences, internal rhythms in a comic? Again, why do we accept that those qualities are in music alone and not everywhere? Yes a drawing in a comic may be read in a narrative context (so, now the story is important again?; Eddie goes in and out of his philosophies as it suits his arguments), but aren’t these drawings lines and textures and compositions as all other drawings?

I could go on, but I prefer to analyze Lee and Kirby’s (et al.) page above from my point of view. I must acknowledge first the fact that it is a segment of a larger story (ten pages). I never write about stories that I’ve never read or are in progress, so I’m breaking one of my rules here… for now… This is wrong because, I don’t know?, judging a comic by one of its pages is the same thing as judging a book by its cover, isn’t it (that’s what Eddie kind of did in Kurtzman’s case)? Also, doing so, it seems to me, dismantles the idea of a comic and leaves the parts hopelessly undone, right? Gérard Genette said that there are two readings in a comics page:

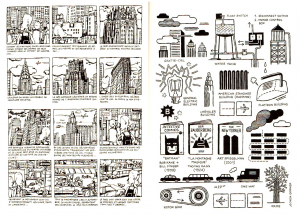

in [visual] forms of narrative expression, such as the [fumetti] or the comic strip (or a pictorialstrip, like the pre-della of Urbino, or an embroidered strip, like the “tapestry” of Queen Matilda), which, while making up sequences of images and thus requiring a successive or diachronic reading, also lend themselves to, and even invite, a kind of global and synchronic look—or at least a look whose direction is no longer determined by the sequence of images.

(As a side note: it’s interesting to realize that the great critic and theorist, one of the literaries if I ever saw one, acknowledges the existence of visual narratives while Eddie doesn’t or tactically avoids acknowledging them.) The successive diacronic reading (what Pierre Fresnault-Deruelle called the linear reading) of words and images gives the reader the succession of events, the narrative. The global synchronic look (what Fresnault-Deruelle called the tabular reading) gives the viewer more of an aesthetic feeling. Both readings exist in all comics and the latter is what Eddie and Noah are talking about when they speak of “something else” and “ab ex.” I doubt that many will read the above page in a linear way (what’s the point: it’s just two guys in funny costumes fighting), but I will do just that:

What we have here is a nine panel grid, a static page layout if there ever was one, which isn’t bad for the intended purpose: the page layout contrasts with the action going on inside the panels. The first panel shows Batroc in one of Kirby’s famous foreshortenings. Another of Kirby’s tropes is the character invading the gutter as seen subtly here. What’s interesting in these three panels is Batroc’s leg in the air pointing up. In the second strip what’s pointing up are Captain America’s hand (when he receives a blow) and, again, Batroc’s arm and hands. Those who have limbs pointing up are losing balance and, hence, are losing the fight. The last strip is pretty much the consummation of the scene with Batroc falling on his back. The last panel depicts post-action fatigue and domination if you know what I mean. The guy who fell into the passive role in the missionary position was feminized and lost the fight. Also interesting is the back of Batroc in the second panel mirroring Cap’s back in the 7th, but with opposite meanings: powerlessness in Batroc’s case and absolute power for Cap. So, not only do these images tell a story, maybe it’s not exactly the story intended for the frantic one (i. e. the infant reader).

What does the global synchronic look tell us, then? First of all there’s a rhythm of circular speed lines and straight shock lines (notice how Cap’s are a lot more powerful than Batroc’s sissified ones) constructing a texture that gave Noah the ab ex aspect that he mentioned. These are there to underline the violence and speed of the actions, but, more than that, to unify and create a relentless cadence in the page design. Here, again, the page functions differently in the three strips: a vertical thin speed line is counteracted in the next panel by a more powerful also vertical one. Things begin to change in that very panel though because the rhythm becomes horizontal until, at the end, returning to vertical completing a full circle with Cap’s might (in crescendo) replacing Batroc’s frailty. The full shot is consistently applied, but the feet deny that on panels one, two, five, six, seven, eight (it’s a device used by Kirby frequently: the characters don’t fit – as a curio see here the same effect used in 1109!). Cap starts on the viewer/reader’s opposite side to end up near his/her standpoint inverting positions with Batroc, in a kind of dance, as we have seen above. The 180 degree rule is broken from panel two to three. The point of view changes around the fighters. There’s a curious symmetry in the page with a kind of knot at the center. The last panel has no gutter (or has a virtual gutter) to show that something changed: the positions are now the same as those in the first panel, but Cap circles his prey in triumph (the symbolic order was restored; citizens may calmly eat their freedom fries again – Batroc, if you don’t know, is French and speaks with a heavy French accent – notice also the stereotypical pencil moustache and beard; I know that Europe was a female, so, it’s only natural that Batroc had to lose in combat against a macho American hero). The colors are loud and out of sync at some places. The background colors divide the page in, more or less, a dynamic diagonal. (If you allow me a personal note I always liked the imperfections of the old coloring.) Cap is garbed in white and primary colors (red and blue), Batroc is secondary colored (orange and purple). Looking at their colors alone no one can deny who will win. All this may seem exhilarating to Eddie, but I suspect that nostalgia plays a role also: “for me this page, and others of a similar stripe, opened up a whole new different way of thinking about comics (I was nine; I’d been thinking about them for quite a few years).”

Who are these people though? From now on Eddie will call me a literary, I’m afraid, but I insist, how come?, I analyzed drawings until now, nothing else! When Eddie asks and answers quite absurdly “how does that Marvel comic stand up if you take away the pictures? It doesn’t.” I say it does, a bit, but not that page above and why is that? That’s right: because if the pictures disappear the story disappears too. Storywise it’s interesting to note the micro-use of the known formula of popular tales (identified by Propp) “win-lose-win.”

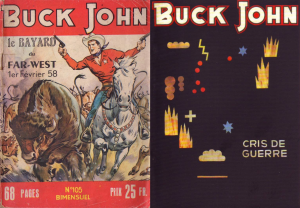

“The Blitzkrieg of Batroc!” is a superhero ten-pager with the usual macho boasting, dick waving contest and misogyny of old comics. The plot (oops!) is simple enough: Cap fights Batroc to save Agent 13 of Shield (aka Sharon Carter). After a plot twist Batroc and Cap team up against agents of Hydra to save the mam’selle who, obviously, has an infatuation for the gallant Nationalist hero. How many times do we need to read another damsel in distress kind of story? I want my time back! See how those nine pages did lack for a full appreciation of the comic?

Am I denying all the good compositional things that I said above about page 8? Of course not, but why should I forget everything else either? And isn’t the final product more important than just an aspect of the whole thing? What’s the meaning of this comic according to your truly? Woman, even if they’re agents of Shield, are frail little creatures who need the strong Nationalist hero to save them from the bad bad guys (that Manicheism again! Jeez!). Jack Kirby may have made the superhero genre his own, but he certainly didn’t make it worthy.

Even worse: the apparently good things said above about page 8 aren’t ultimately in the service of a formula as noted already? (As I said elsewhere, the game is rigged: the dashing Nationalist hero always wins.) And how about the innocuous violence? Isn’t it going to give the impression to the frantic ones that it’s OK to beat the crap out of the bad guys (violence is an abstraction, after all)? Are the frantic ones, or their modern day descendents, doing it right now somewhere, on this poor planet Earth, in the holy name of the plutocracy?

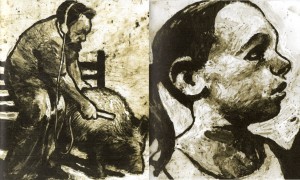

![Felipe Hernandez Cava (w), Federico del Barrio (a), Lope de Aguirre, La conjura [Lope de Aguirre, the conspiracy], Ikusager, 1993.](https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Aguirre-227x300.jpg)

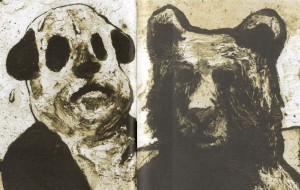

![Stefano Ricci, La storia dell'Orso [the bear's story], Quodlibet, 2014.](https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Orso-1-269x300.jpg)