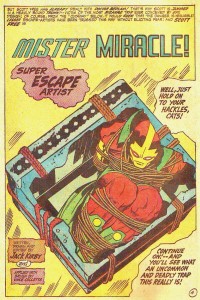

DC Comics’ “Himon!” by Jack Kirby (Mister Miracle # 9, Jul.-Aug. 1972) is not the comics story that I hate the most. That dubious honor, if I remember correctly, goes to Pedro and Me (2000) by Judd Winick, but since there’re 100 miles between yours truly and my copy of said “graphic novel,” “Himon!” will have to do as a target for my participation in the 5th Anniversary Hooded Utilitarian Hate Roundtable. “Himon!” isn’t even the worst Jack Kirby story… on the contrary, Charles Hatfield, in his book about Kirby Hand of Fire (2012, 206), included it among “the most deeply personal comics Kirby ever made.” Since Charles did such a good job analyzing “Himon!” I must agree with him that said story has its merits. This is good because I don’t want to incur in the same fault I accuse superhero comics artists and writers of (i. e.: of being Manichean). Then again is it fair to judge an artist for a really small amount of his input while most of it is big corporation owned dreck produced in a work-for-hire situation? In any case I’ll use other aspects of Boy Commandos, New Gods, The Eternals and the aptly titled Mister Miracle Super Escape Artist series to illustrate my points.

1 – Manicheism:

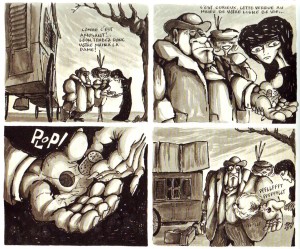

“Mystivac!,” Mister Miracle # 12, Jan.-Feb. 1973.

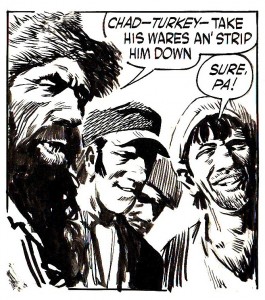

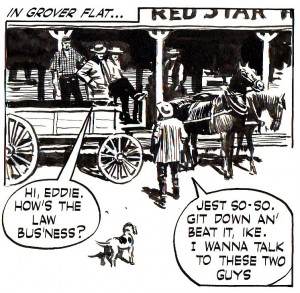

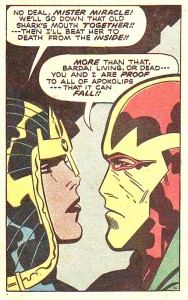

Jack Kirby’s superhero comics are Manichean. Reality is seen in black and white in these primary colored comics. From a purely visual point of view this means that the baddies are ugly (as seen above) and the goodies are mostly good looking. We can find the roots of this line of thinking in the ancient pseudoscience of physiognomy: the absurd idea that one’s outer appearance is a mirror image of our personality. To further examine how Jack Kirby used physiognomy we just need to compare Mister Miracle and Big Barda…

“Apokolips Trap!!,” Mister Miracle # 7, Mar.-Apr. 1972.

…two young athletes owning handsome physical appearances… with Granny Goodness and Darkseid below…

“The Pact!,” New Gods # 7, Feb.-Mar. 1972 (as reprinted in Jack Kirby’s New Gods # 4, Sept. 1984). Scott Free (Mister Miracle) arrives in Apokolips. (Stupid! Stupid! Garish colors! Give me old Benday Dots anytime! And yet, need I say it?, this is still thousands of times better than today’s gradient-ridden computer coloring.)

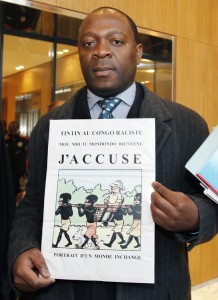

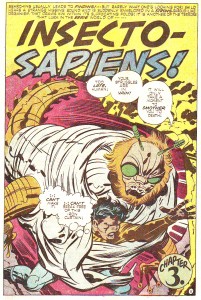

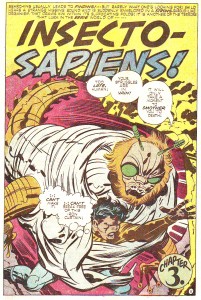

The former is an old woman and the latter is a stony faced Neanderthal. The baddies’ mugs are more masks than proper faces; their facial expression (it’s mainly one) shows that they’re always in a bad mood. In a Manichean war of good vs. evil Jack Kirby equated good with youth and good looks and evil with old age and other species or subspecies. We can’t also forget that young people were the reading target for these comics (Kirby’s clients) and our shallow hedonistic media revere youth and good physical appearances. Instead of choosing racist stereotypes like Ming in Flash Gordon (fortunately Jack Kirby may be accused of many things, but not of being a racist – Mister Miracle # 15, for instance, is there to prove it), Jack Kirby, as I mentioned above, advocated speciesism. His bad guys were surely insect-like and reptilian (with the occasional furious cat, mad dog, and devilish goat thrown in for good measure).

Insecto-Sapiens! Untitled, Mister Miracle # 16, Oct.-Nov. 1973.

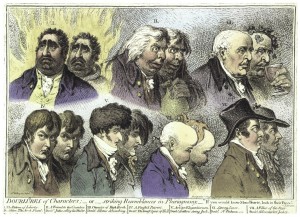

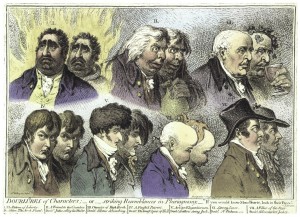

(Below is an intelligent attack on physiognomy – I know, it’s an easy target, but still…)

James Gillray, “Doublures of Characters or striking Resemblances in Phisiognomy. “If you would know Men’s Hearts, look in their Faces.”,” Anti-Jacobin Review and Magazine, November 1, 1798. On an unrelated note: look at the hand-coloring and weep!

Manicheism, of course, is part of an us vs. them ideology in which we, obviously, are always the good guys. Listen to Jack Kirby himself (in “Kirby on Survival,” Jack Kirby’s New Gods # 6, 1984):

They are evil, we are good. They are plotters and traitors, we are loyal and clever.

In “Himon!” Manicheism is still a problem, but at least it is aptly used to show how, in a dictatorship, almost everyone (Auralie, for instance, is an exception) is infected by the ugliness of the leader.

To paraphrase Charles Hatfield in Hand of Fire (219), everyone’s infected… “Himon!,” Mister Miracle # 9, July-Aug. 1972.

2 – Formula:

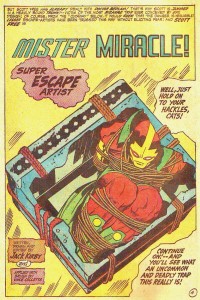

It’s no secret: superhero comics are formulaic. If you let me indulge in a personal note for a sec. I must say that this is reason enough to stop me from enjoying these stories: if the comic is Manichean and it’s just an endless row of fights why should I bother reading it if I know beforehand who will win? This is exactly what happens in most of the boring issues of the Mister Miracle Super Escape Artist series: Mister Miracle vs. Steel Hand; Mister Miracle vs. Overlord and Granny Goodness; Mister Miracle vs. Doctor Bedlam; etc… etc… ad nauseam… Trying to understand why people like these comics and films I suppose (and I use the word advisedly because this is no scientific conclusion) that readers and spectators like to feel the epinephrine of violent action (without the consequences produced by violence in the real world, of course). They also like to root for the righteous good guys… It’s kind of a sports thing, I guess…

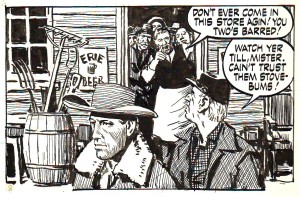

Joe Simon and Jack Kirby in self-referential mode. Boy Commandos # 1, Winter 1942 – 43 (as reprinted in Mister Miracle # 6, Jan.-Feb. 1972).

In the image above two characters that stand for Joe Simon and Jack Kirby explain how “[They]’ve been getting [their] characters in and out of jams.” That pretty much sums it all up: in these formulaic comics the heroes get in a jam and, then, they get out of it. In Mister Miracle # 5 the baddie, Virman Vundabar, says to Mister Miracle, after he got out of yet another jam (to quote the fanboys when talking about art comics: “yawn!”):

I know! A mother box! [everything is emphatic in these stories] With the aid of a mother-box, you thinned your atomic structure and transferred yourself out of the coffer!!

To which the latter answers:

Not so! […] I play it fair — and you know it!!!

Mister Miracle won by three exclamation marks to two. On the other hand I reckon that he was wrong and the baddie was half right: it wasn’t the mother box that saved Mister Miracle, but he was far from playing it fair. He escaped because of the formula imposed by the author, Jack Kirby. The game is definitely rigged. In “Himon!” the same thing happens to ruin my enjoyment of the story. The dei ex machina are an easy solution to every problem: Scott Free (Mister Miracle) is blinded by the ideology imparted in Granny Goodness’ school?, no matter, Metron and Himon will put him out of his wrong ways; Himon is killed by an angry mob?, of course not, he has the ability to replicate himself (it was one of those replicas that seemed to be assassinated); Scott Free fights some of Darkseid’s minions?, piece of cake… he easily wins… etc… In conclusion: Everything is too easy for yours truly’s taste.

“Himon!,” Mister Miracle # 9, July-Aug. 1972: you bet that’s not him.

3 – Cardboard Characters:

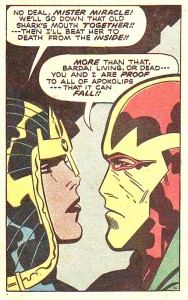

These characters are as thin as the paper they were printed on. Mister Miracle barely exists. At the beginning he’s just a strange being who came from another world. We know nothing about him except that he’s a super Houdini. From Mister Miracle # 4 (Nov.-Dec. 1971) until Mister Miracle # 7 (Mar.-Apr. 1972) a series of short stories (two and four pages) give us some feedback to understand Scott Free a little better, but is that enough? He was born in Goodiesland (aka New Genesis), but because of some kind of pact between Darkseid and Highfather (a kind of Moses) he was transferred to Baddiesland (Apokolips) where he grew up in Granny Goodness’ orphanage to become part of Darkseid’s military elite. The truth is that no real characterization exists. If the hero (the main character) is flat what can we expect for the other characters? Nothing at all…

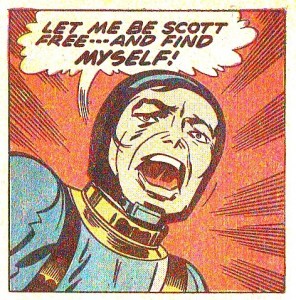

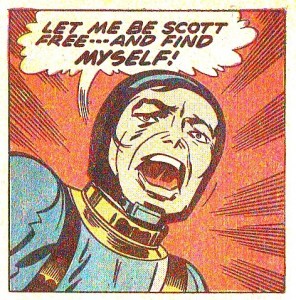

At the end of “Himon!” we find the melodramatic panel below:

“Himon!,” Mister Miracle # 9, July-Aug. 1972. Is that eye leaving stage left?

That’s OK, by me, but… who are you exactly? How can one find something that doesn’t exist?

These cyphers can only be used as personifications in allegories, but we all know how heavy handed that can be. Plus: a Manichean one can only achieve kitchy results… Certainly not the status of great art that some claim for Kirby’s work…

4 – Glorification, Glamorizing, Sanitation of Violence:

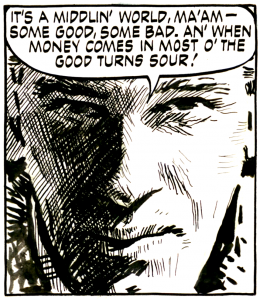

This is the part in which my love/hate relationship with Jack Kirby’s art reveals itself. Not being completely blind I can see how (see above when I guess why people like action comics and films) the drawings are powerful. That’s exactly the problem: they’re too powerful. So much so that Art Spiegelman put the topic in the following terms (in The Comics Journal # 181, Oct. 1995, 106):

[…] the triumph of the will, the celebration of the physicality of the human body at the expense of the intellect, is very much an impulse in Fascist art. It has a lot to do with the motor for Kirby’s work, even though I understand that his work is filled with characters who fought the Fascists.

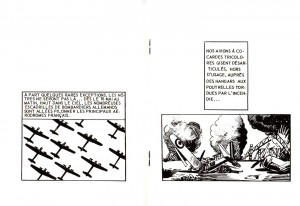

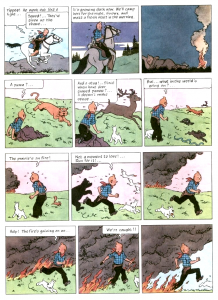

Kirby’s double-page spreads are particularly good examples of the above. With them Kirby aimed to grab the reader by the guts from the beginning. To do so he knew that he needed to create the most spectacular images that he could muster. This meant huge battle scenes with lots of what Charles Hatfield called Kirby’s technological sublime and the clash of titans.

“Earth — The Doomed Dominion,” New Gods # 10, Aug.-Sept. 1972 (as reprinted in Jack Kirby’s New Gods # 5, Oct. 1984). The mannerist composition dividing the realm of the gods from the realm of the humans (or… whatever they are) is quite interesting.

We have seen that there are a few problems with Jack Kirby’s superhero stories, but enlightened readers tend to value the drawings and the drawing style instead of the narratives. As if the former can be, in comics, totally separated from the latter. It can’t: both the iconical content of the drawings and the lines as such are a unit, a meaning generator. The Manichean content, for instance, is in the text, but it is also in the narrative drawings, as we have already seen. Plus: it’s the lines, colors, and textures that convey the physicality and the powerfulness of the images; marks have meanings. Kirby’s graphic style is a cubo-futurism that underlines and glorifies, technology, youth and violence. In the above panel, for instance, extreme violence is given to us in awesome spectacle. Being a children’s comic the nasty consequences of such a shock are spared to us because these are super beings and nothing can really harm them. What escapes my reckoning is why do they attack each other if there are no consequences of the attack? Logic doesn’t matter though, what really matters is that the kinetic and colorful show must go on.

Czech writer Milan Kundera wrote the following about kitsch (in The Unbearable Lightness of Being, 1984, 248):

Kitsch is the absolute denial of shit, in both the literal and figurative sense of the word; kitsch excludes everything from its purview which is essentially unacceptable in human existence.

Also (253):

Kitsch is a folding screen set up to curtain off death.

Giving us not only a fascistic glorification and aestheticization, but also a sanitized version of violence Jack Kirby’s work is the perfect embodiment of kitsch.

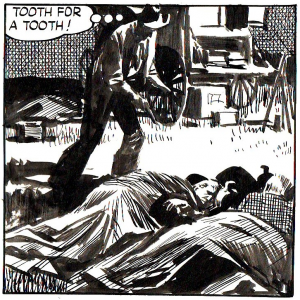

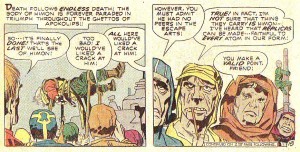

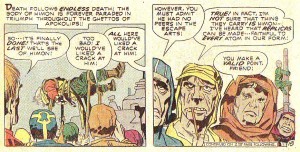

Again, “Himon!” is a bit different. In the below panel we don’t see them exactly, but innocent people die (my question is: aren’t Jack Kirby’s readers so inured to violence that they couldn’t care less? Besides, who cares about cyphers?):

“Himon!,” Mister Miracle # 9, July-Aug. 1972.

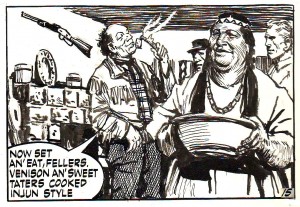

5 – Feminism?

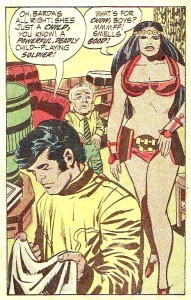

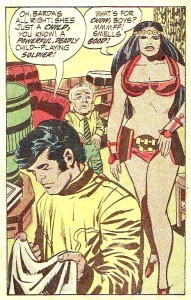

Of course not. Even if Big Barda is a physically empowered woman (as we have seen, there’s no intellect in Jack Kirby’s comics) look below to see who the only scantily clad character is:

“The Closing Jaws of Death!,” Mister Miracle # 4, Sept.-Oct. 1971.

On the other hand the panel below could be a poster to announce a SlutWalk, so, I may be wrong…

“Mystivac!,” Mister Miracle # 12, Jan.-Feb. 1973.

In conclusion (a):

(After probing into a small part of a huge corpus):

On the mass culture side of things Jack Kirby not only contributed enormously to the superhero mythos, he also inspired ideas for films like Star Wars, Man in Black, or Pure Steel (more than dubious feathers to wear in one’s cap, but anyway…).

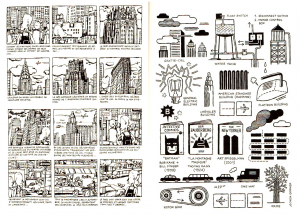

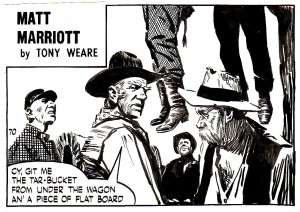

Jack Kirby’s superhero stories are Manichean formulaic romps performed by cardboard characters. His drawing style and visual imagery are an emphatic cubo-futurist fascistic glorification and glamorizing of violence, youth and technology. On the positive side he was particularly good creating complex panel layouts and used the comics medium to great effect sometimes; for instance (note the sequence of the archers’ movements from left to right):

“Apokolips Trap!!,” Mister Miracle # 7, Mar.-Apr. 1972.

Jack Kirby could also surprise the reader from time to time breaking, for example, the dichotomy handsome/good vs. ugly/bad:

“Mother!,” The Eternals # 10, Apr. 1977.

Other times he committed crass mistakes. Probably because of an excess of work and deadline pressure:

The final sequence of “Paranoid Pill!,” Mister Miracle # 3, July.-Aug. 1971.

The continuation of the sequence above in “The Closing Jaws of Death!,” Mister Miracle # 4, Sept.-Oct. 1971. Where did those ropes come from?

Being such a loud comics artist Jack Kirby’s work seems to have been created by his character Funky Flashman. Even if said character is a caricature of Kirby’s, by then, rival Stan Lee…

Conclusion (b):

What about “Himon!,” then? It’s as simplistic and Manichean as all the other stories, but, at least, Kirby used Manicheism to show how the dictator’s ideology infects the people (the “lowlies”). The narrative formula is also there (the use and abuse of the dei ex machina, Metron and Himon, is too facile a device; on top of that Scott Free can’t lose a fight and he can’t be killed – even if “in a jam” we know that he will end up all right). The characters are flat, but, at least, there’s some internal conflict in Scott Free (that’s a slight improvement over other, more pedestrian, stories). Apart from the above there are some pursuits, fights, and explosions (yawn!) and the usual glamorizing followed by sanitation of violence. The sequence in which Willik orders the burning of the “lowlies” may go against the grain (up to a point, as we’ve seen above), but that’s one exception, not the rule. So is the story “Himon!” in Jack Kirby’s oeuvre.

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.